Let me first lay my bias and experience cards on the table. I’ve been a member of the Christian conservative wing of the Republican Party from the moment I could vote until 2016, when the Republican Party left me behind by crossing multiple red lines in its embrace of Donald Trump. Before I became a full-time writer and journalist, I wasn’t just a Christian conservative voter, I was a pro-life activist and constitutional litigator for pro-life and religious liberty legal organizations.

If there was any American subculture that I knew well, it was American Evangelicalism—especially the most politically engaged branch of the movement—and while I knew it had its flaws (every human movement does), I did not believe that racism was one of them. In fact, I knew it wasn’t. One of the core arguments of the modern pro-life movement is that abortion rights were rooted in part in eugenic racism, in a desire to weed out “undesirable” populations. Pro-life activists are continually pointing and condemning the disproportionate number of abortions in the African American community.

So imagine my surprise when I began to see an increasing amount of argument that, actually, racism taints the rise of the religious right. Critics claim that the modern narrative of conservative Evangelical activism is built on white supremacy. Rather than Roe v. Wade shocking Evangelicals into action, the true catalyzing event was allegedly the 1970s-era IRS attack on so-called “segregation academies”—the whites-only Christian schools that sprang up across the South in response to federal desegregation orders.

According to this narrative, Evangelical leaders mainly supported abortion rights. They jumped into the culture war only when the IRS moved to strip the tax exemptions from racially discriminatory schools. Opposition to integration is the poisonous acorn that grew into the mighty political oak of conservative Christianity. .

Writing this week in GQ, Laura Bassett relied on this very argument to claim that the pro-life movement was “always built on lies.” Parts of her argument were a mess. For example, she initially wrote that George Wallace was a former Republican governor of Alabama and thus attributed his racist arguments in support of abortion the GOP. He was a Democrat, and his claim that black women were “breeding children like a cash crop” advances the pro-life anti-racist narrative. That’s exactly the hate it stands against.

So, what is the truth here? Does the pro-life movement have racist roots? The short answer is “not really.” The longer answer is complicated. As my colleague and our Dispatch Podcast host Sarah Isgur is fond of saying, “Let’s dive right in.”

One of the most comprehensive arguments for the racist roots of the religious right rests comes from the work of Dartmouth professor Randall Balmer. Indeed, he points to some historical facts that would shock the conscience of many younger Evangelicals—especially younger Southern Evangelicals.

First, it’s true that major Protestant denominations largely supported abortion rights when Roe was decided, including the Southern Baptist Convention. Here’s Ballmer:

Both before and for several years after Roe, evangelicals were overwhelmingly indifferent to the subject, which they considered a “Catholic issue.” In 1968, for instance, a symposium sponsored by the Christian Medical Society and Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of evangelicalism, refused to characterize abortion as sinful, citing “individual health, family welfare, and social responsibility” as justifications for ending a pregnancy. In 1971, delegates to the Southern Baptist Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, passed a resolution encouraging “Southern Baptists to work for legislation that will allow the possibility of abortion under such conditions as rape, incest, clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother.” The convention, hardly a redoubt of liberal values, reaffirmed that position in 1974, one year after Roe, and again in 1976.

He continues:

Although a few evangelical voices, including Christianity Today magazine, mildly criticized the ruling, the overwhelming response was silence, even approval. Baptists, in particular, applauded the decision as an appropriate articulation of the division between church and state, between personal morality and state regulation of individual behavior. “Religious liberty, human equality and justice are advanced by the Supreme Court abortion decision,” wrote W. Barry Garrett of Baptist Press.

The true catalyst for Evangelical engagement, Ballmer argues, was a different case entirely—a federal district court case called Green v. Connally. In Green, the court held that “racially discriminatory private schools are not entitled to the Federal tax exemption provided for charitable, educational institutions, and persons making gifts to such schools are not entitled to the deductions provided in case of gifts to charitable, educational institutions.”

It was at this moment that Paul Weyrich, one of the founding fathers of modern religious conservatism, believed he found the issue that could wake the sleeping giant of American Evangelicalism. Weyrich had a theory about the potential strength of the “moral majority,” but he couldn’t find an issue to catalyze the movement. Again, here’s Ballmer:

For nearly two decades, Weyrich, by his own account, had been trying out different issues, hoping one might pique evangelical interest: pornography, prayer in schools, the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, even abortion. “I was trying to get these people interested in those issues and I utterly failed,” Weyrich recalled at a conference in 1990.

But then, “When ‘the Internal Revenue Service tried to deny tax exemption to private schools,’ Weyrich said in an interview with Conservative Digest, that ‘more than any single act brought the fundamentalists and evangelicals into the political process.’”

IRS actions against Christian schools enraged Jerry Falwell (he operated Lynchburg Christian School) and racially discriminatory Bob Jones University. Evangelicals sent 125,000 letters of protest to the IRS objecting to proposed regulations that would require segregation academies to admit a certain number of minority students.

Make no mistake, this is a deeply troubling narrative. But let’s keep going. It turns out that while the attack on segregation academies undeniably motivated some people, it could not transform American politics. Not even close.

Ballmer clearly notes that outright racism could not, in fact, create a mass movement. In his words, he says that Falwell and Weyrich were “savvy enough to recognize that organizing grassroots evangelicals to defend racial discrimination would be a challenge.”

So what was the issue that could mobilize the masses? I’ll give you a hint—it wasn’t defending segregation academies. It was abortion. Again, here’s Ballmer:

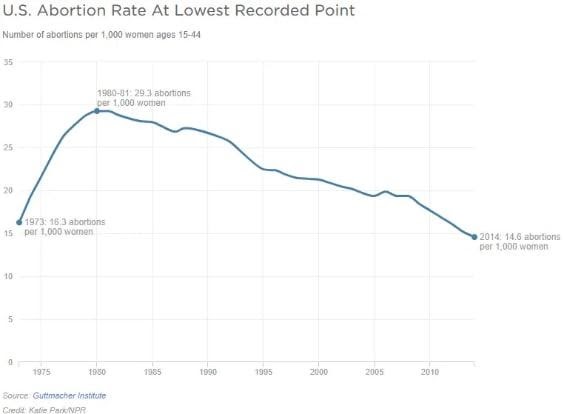

By the late 1970s, many Americans—not just Roman Catholics—were beginning to feel uneasy about the spike in legal abortions following the 1973 Roe decision. The 1978 Senate races demonstrated to Weyrich and others that abortion might motivate conservatives where it hadn’t in the past.

In short, the times were changing. Arguments that didn’t work in the past were working now. Ballmer smartly points to a key film series from Francis Schaeffer and C. Everett Koop called Whatever Happened to the Human Race? It was produced in 1979, but it circulated in Evangelical America for years afterward. I saw it in Sunday school during high school, and it made a profound impact on me.

A young conservative Christian growing up in 1980s America heard nothing about segregation academies. Indeed, when the Reagan administration ultimately led the final legal charge to strip tax exemptions from Bob Jones University—culminating in an 8-1 Supreme Court decision in 1983 holding that the Free Exercise Clause could not protect the university from IRS action against race discrimination—the decision barely raised an eyebrow. The defense of segregation academies ended not with a bang, but a whimper. The defense of life, however, roared on.

Moreover, let’s take a second look at the Baptist flip-flop on abortion. It’s critical to note that the 1960s and 1970s were a time of enormous confusion, upheaval, and anguish in American Protestant Christianity. The largest denominations were liberalizing theologically at an astonishing rate—and the liberalizing leaders turned out to be dramatically out of step with the masses of men and women in the pews.

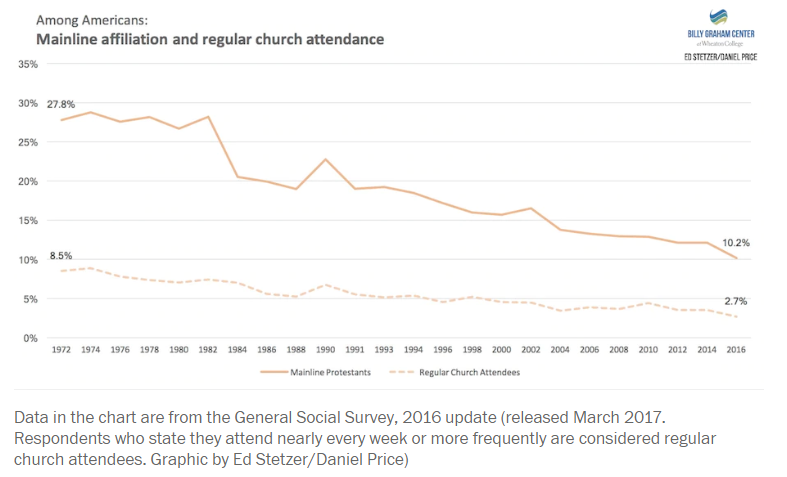

The Protestant Mainline, once the dominant Protestant faction of Christian America, has been bleeding members since the early 1970s at a startling rate. By some measures, the rate of decline is so great that membership could reach near-zero within the next quarter-century:

But which denomination zigged conservative while its Mainline brothers zagged progressive? The Southern Baptist Convention. Books have been written about the “conservative takeover” of the SBC, but it’s clear that the Roe-era SBC underwent a fundamental transformation.

While the Mainline denominations shrank, the SBC enjoyed a period of remarkable growth—from roughly 11 million members in the mid-1960s, to a peaking above 16 million in the mid-2000s. Membership has since declined to slightly less than 15 million presently, but these numbers indicate rapid seismic shifts in American religious membership and belief. In short, a lot more was going on between 1970 and 1980 than a sudden interest in preserving southern segregation academies. Millions of Christians were leaving their traditional spiritual homes in search of new churches. At the same time, abortion was on the rise. If you think that the “spike” in legal abortions wasn’t that dramatic—look at the raw numbers, from the pro-choice Guttmacher Institute:

So, no, the pro-life movement wasn’t “built on a lie.” It’s not the mighty political oak born from a racist acorn. It’s ultimately the product of the combination of seismic religious and cultural changes and patient religious and political argument.

To make this claim about pro-life activism isn’t to absolve white American Evangelicalism of any racist taint. But the sins of the past don’t center around abortion. They don’t even center around religious liberty (despite the defense of segregation academies in the 1970s.)

Ultimately, the great sin of white southern Evangelicalism is that for generations its faith did not transcend and displace its culture. Instead, all too often that faith was placed in service of the very culture it should have transformed. For more than 100 years, if you were going to draw a Venn diagram of white Southern supporters of Jim Crow and white southern fundamentalists and Evangelicals, you would see an extraordinarily high degree of overlap.

I emphasize the South not because racism is limited to the South but because no other region of the country so saw such concentration of racism and Protestant religiosity. It’s here (I live in Tennessee) where racism and religion were so thoroughly mixed, and it’s here where you’ll still find the seat of American Evangelical electoral power.

But the Evangelical South—which followed the pro-life lead of the Catholic Midwest and Northeast—is not pro-life because it was racist. Racism is no longer a factor in its support for religious liberty. Battles over segregation academies are largely looked upon with regret and shame. Rather it became more overtly pro-life as it (slowly and imperfectly) started to shed its racist past.

That racist past still matters, however. It provides one answer to the long-standing question, “Why don’t culturally conservative white and black churches unite on social issues?” Especially in the South, there’s quite simply too long of a history of bigotry and prejudice—or indifference to bigotry and prejudice—to quickly reform a united church. Bygones can’t be bygones, at least not yet.

The consequences of centuries of subjugation are too profound. Millions of black Americans live with them every day. It’s difficult to form political coalitions across lines so starkly drawn, and it’s hard to erase those lines when for centuries they were etched in steel and blood.

Rest in peace, Ravi Zacharias.

Earlier this week, the world lost one of its leading Christian apologists. Ravi Zacharias died after a brief battle with cancer. I’m going to write more about Ravi in a future newsletter (he played a key role in a religious awakening in the Ivy League that needs its own full story), but I do want to note one deeply meaningful aspect of his ministry. He understood the true role of the Christian apologist more than anyone I’ve ever known.

There’s a vision of an apologist as the church’s gladiator in the marketplace of ideas. He’s the man or woman who walks into hostile territory, takes on the unbelievers on their home turf, and not only walks away unscathed, he may even pocket a convert or two. And Ravi would indeed go virtually anywhere and talk to anyone to defend the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

But there was so much more to his ministry than confrontations with people who did not share his faith. Ravi also served as an apologist for Christianity to the church itself. Countless Christians come of age uncertain of their beliefs. They go to Sunday Schools that vary wildly in quality, listen to pastors who often don’t speak directly to their concerns, and grow up in homes with parents who also struggle to answer the great questions of life.

By taking on the hardest questions—and doing so with particular clarity—Ravi filled the void left by, for example, a youth pastor who couldn’t engage with the problem of pain. He wrestled honestly and thoughtfully with questions about death, hell, and eternal life. It’s not that he answered so clearly that he resolved all debate (no person can do that), but he made countless Christians understand that their faith did indeed have a firm intellectual and philosophical foundation.

I want to briefly acknowledge that he did face some controversies later in life. You can read about them here. Rare indeed is the believer who lives a half-century in the public eye and who does not show that—like we all—he is prone to sin. But that’s all over now. That sin is a crumbling dry leaf that disintegrates before the hurricane of God’s eternal grace.

Thank you for your life’s work, Ravi. We will miss your presence, but we rejoice as you enter into the eternal joy of Jesus Christ.

One last thing …

In a previous newsletter, I mentioned that I’ve been spending time listening to older Christian music. I mentioned the late Rich Mullins. He wrote this song shortly before he died, and it’s a powerful expression of doubt, pain, and—ultimately—faith. Here it is, performed years later, at a tribute concert. Enjoy:

Photograph by Ricky Carioti/Washington Post/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.