Dear Reader,

“Conservative intellectuals launch a new group to challenge free-market ‘fundamentalism’ on the right.”—Washington Post, February 18, 2020

Oren Cass, a very bright fellow and decent guy, has launched a new organization, American Compass. Joining him are some other very bright people—some of whom I know, others I know by reputation. I do not worry that any of them—particularly Michael Needham or David Azerrad —are ersatz socialists or champions of dirigisme (which, I’ll have you know, I spelled correctly on the first try).

I think it is entirely possible I will end up agreeing with some, or even most, of their forthcoming policy proposals. Which is to say that the following criticism centers on framing, history, politics, and first principles. We’ll have to wait and see on what policy proposals flow from those first principles.

The Post’s James Hohmann begins his article:

Oren Cass believes conservatives have blundered by outsourcing GOP economic policymaking to libertarian “fundamentalists” who see the free market as an end unto itself, rather than as a means for improving quality of life to strengthen families and communities.

One paragraph in, I’m already reaching for my red pen.

I keep hearing people say or imply that libertarians and free market “fundamentalists” have been running the show in Washington. I honestly have no idea what they’re talking about—and neither do any libertarians I know. In fairness to Cass, he doesn’t make the barmy claim that Washington has been run by libertarians, just the slightly less barmy claim that Republican party has been. I still have no idea what he’s talking about—and, again, neither do any libertarians I know.

(As an aside, whenever I hear arguments that Group X is running everything, I know I’m dealing with an argument that is spiced with some dosage of conspiratorialism and exaggeration. Here’s a newsflash: No one is running everything—not the Deep State, not the Jews, not the Frankfurt School Marxists, the globalists, the donor class, or the lizard people. One of the great things about advanced democracies is that every faction is competing for power and influence and none of them ever fully succeeds. Even when one faction dominates the conversation or policymaking, it isn’t long before they overstep, atrophy, or lose their mojo because even limited success tends to dissolve the reasons for certain coalitions to come together in the first place. It’s a bit analogous to Joseph Schumpeter’s argument for why monopolies cannot long endure so long as they are not protected by the state. Monopolies create the circumstances for their own demise as more nimble entrepreneurs innovate them into obsolescence.)

George W. Bush: Market fundamentalist libertarian?

The last Republican president before Trump was George W. Bush, who campaigned on “compassionate conservatism” which was often defended by its proponents as “big government conservatism” or “strong government conservatism.”

Was President Bush a free market fundamentalist or libertarian?

The question answers itself. But if you need reminding: Under Bush we had the largest expansion of entitlements since the Great Society. Sen. Judd Gregg called it “the largest tax increase that one generation has put on another generation in the history of the country.” We got a new Cabinet agency, the Department of Homeland Security (not a famous hotbed of libertarians). The Department of Education’s budget doubled under President Bush. There were huge spending increases on transportation, agriculture subsidies and the like. Indeed, the total number of subsidy programs grew by roughly 30 percent over the course of his presidency. And of course there were the bailouts of the financial crisis.

At one point, The Economist ran a cover story asking, “Is George Bush a socialist?”

And, just to be clear, during this entire period the libertarians who were supposedly running everything were complaining very loudly that they had no say in anything.

This is not to suggest there were no free market initiatives under President Bush. His attempt to privatize Social Security is the most notable example. But it’s worth noting that that failed—which presumably wouldn’t have happened if libertarians were running the show.

My aim here isn’t to castigate President Bush, it’s merely to point out that when he was president, nobody—at least nobody to the right of The Nation—thought he was a market fundamentalist or libertarian.

The history that wasn’t.

A bit further down in the article, we’re told this:

Inside the GOP coalition, Cass argues, traditional economic conservatives ceded economic policy to libertarians as part of a “bargain” to win the Cold War. Ronald Reagan called it a three-legged stool: economic libertarians, social conservatives, and national security hawks. Cass believes this “fusionism” worked well—in the past. “When you had a situation where the free market was delivering the social outcomes that conservatives most prized, libertarians and conservatives tended to agree,” he said. “What we’ve seen more recently is a growing understanding that the market does not necessarily in all cases deliver a set of social outcomes that conservatives prize.” (emphasis mine)

Then in the very next paragraph, we’re told this:

Markets are good, Cass explained, but life is about so much more than markets. He said American conservatism historically had a richer conception of the role of government beyond maximizing returns, such as strengthening domestic industry. He lamented the growing concentration of wealth, geographically on the coasts and in the big cities, as well as in a handful of industries, which has accelerated income inequality. (emphasis also mine)

Do you see the problems?

In the first paragraph, we’re told that in the past, conservatives and libertarians were on the same page because the free market was producing results we all liked. Only recently have some enlightened conservatives come to understand “that the market does not necessarily in all cases deliver a set of social outcomes that conservatives prize.” But in the very next paragraph we’re told that conservatives used to have “a richer conception of the role of government beyond maximizing returns.”

Well which is it? Perhaps he believes that the Nixon, Eisenhower, Reagan, or Bush I administrations were suffused with this middle-way wisdom, balancing the demands of the market and the needs of industry and society. Okay, I’m open to that I guess. But he also contends that no one saw the downside of the free market because the free market was only producing results that “conservatives most prized.” I have a hard time figuring out how you can contend both premises are true simultaneously.

Moreover, I still have no idea what he’s talking about. Who are these conservative free market fundamentalists who didn’t understand that the market might produce outcomes they don’t like? Is the observation that there’s a “richer conception of government beyond maximizing returns” really a sudden revelation to conservatives today? I mean even Jack Kemp understood this.

I suggest people who believe this strawman’s history of conservatism read Irving Kristol’s Two Cheers for Capitalism or “When Virtue Loses All Her Loveliness.” Or Russel Kirk’s “Libertarians: Chirping Sectaries.” Heck, read Friedrich Hayek (praise be upon him). He was open, at least in principle, to universal health insurance and a universal basic income.

Neither socialism, Nor capitalism.

One of William F. Buckley’s favorite quotations came from Willi Schlamm: “The trouble with socialism is socialism. The trouble with capitalism is capitalists.” This was not Buckley’s backhanded way of saying capitalism was perfect, it was his way of underscoring that in a free society you will inevitably get free riders and other remoras and exploiters who will try to game the system in ways that are contrary to the health of the system.

James Burnham made a similar point at book length in his magisterial The Managerial Society. He wrote:

Not only do I believe it meaningless to say that “socialism is inevitable” and false that socialism is “the only alternative to capitalism”; I consider that on the basis of the evidence now available to us a new form of exploitive society (which I call “managerial society”) is not only possible but is a more probable outcome of the present than socialism.

My most recent book is a full-throated defense of liberal democratic capitalism, but as the title suggests, Burnham was a considerable influence on me. His Managerial Society thesis, itself heavily influenced by Schumpeter, was that a new class of intellectuals, managers, social workers, and planners constituted the real ruling class in society. I think the new class wasn’t—and isn’t—as monolithic as Burnham suggested, but I think his analysis gets much closer to the truth of the matter. The mixed economy of the United States is closer to corporatism (or if you prefer, crony capitalism) than socialism or a true free market system. And in a corporatist system, competing elites vie for control of the commanding heights of the economy.

For a century, progressive elites eager to take the reins of government planning insisted they were merely trying to contain “unfettered capitalism.” That capitalism has exited each decade with more fetters around its neck and ankles than it had when it entered was always lost on them.

“Unfettered capitalism” is not a description of what we have, it is a description of a mythical dragon supposedly breathing down our necks, that the planners use to acquire more power to fight it.

What vexes me about the rhetoric of Cass’s project—and that of so many conservatives these days—is that they are simply mimicking the rhetorical tactics of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, not to mention, William Jennings Bryan, Herbert Croly, Teddy Roosevelt, FDR, LBJ, et al. Now these conservatives are making it bipartisan: Our real, biggest, problems stem from our refusal to regulate capitalism enough—or at all.

This is nonsense on stilts (and it’s on stilts in order to take a jetpack down from the shelf and fly away).

Markets, what do they do?

Cass suggests that markets are truly good only when they produce outcomes “conservatives prize.” Come on, that’s not the deal. In different eras, with different forms of conservatism, the market helped to undermine slavery and Jim Crow. The market helped the case for women’s suffrage. The market also made Steve Gutenberg a star. Which is to say, the market isn’t always predictable. The notion that the free market is good but only when we like what it does is bonkers. It’s bonkers morally and politically—and it’s bonkers epistemologically.

Morality: The market is the realm in which we exercise many of our most cherished liberties and rights. In a free society, where the right to pursue happiness is an individual right, not a collective one, some people will pursue definitions of happiness that will not conform to other peoples’ understanding of what is good or proper. And, yes, a thousand times yes, the government sometimes must intervene when this happens. But it must do so judiciously, with a full appreciation of the trade-offs and the facts on the ground.

Politically: Put aside the fact that a lot of the stuff Cass seems to like is stuff progressives like too; let’s assume there are real differences. How will this work? The free market is glorious when it delivers “wins” for the Republican coalition but it’s wrong at all other times? I want to see GOP senators take that on the stump.

And then there’s epistemology. Friedrich Hayek’s warnings against planning were not aimed solely at a particular ideology, but against the folly of planning itself. Yes, they were delivered with particular force against socialists and other social engineers of the left because when he was writing, it was the left that was most vocally in favor of economic planning. The left believed that experts in some office in Washington (or Moscow or Berlin) could better define, dictate, and anticipate the wants and desires of millions of people and thousands of communities across our vast country (some even believed they could do it across the globe). But in no way did he believe that the Brahmins of the managerial class would fail or trample liberty (or both) simply because they were pursuing outcomes un-prized by conservatives. He believed—and I would argue demonstrated—that they would fail because planners cannot outthink markets or command more information than is contained in prices. This admonition applies no less to conservatives who would substitute their preferences for those of citizens than it does to progressives.

Cass says he believes that economic liberty and individual freedom are still “vital,” and I believe him. And, again, I suspect that the policy proposals that American Compass will put forward will mostly be well within the guardrails of reasonableness, even if I end up disagreeing with some of them.

But I also suspect that their task will be more difficult if they actually believe what they say and act as if they are battling a capitalism that sits on a throne rather than one that stands quite fettered.

Various & Sundry

So I’m really going to try to start delivering more than one G-File per week. My wife, who made a fantastic beef Wellington on Monday night so she can officially do no wrong for at least a week, says it’s a bad idea. The G-File’s brand is a Friday thing, she says, like huffing airplane glue after your last class of the week or attending the running of the basset hounds at the local raceway (she didn’t say that part).

But part of the deal is that folks need to become a paying member. We would love it if as many of you as possible came aboard before—or shortly after—the door clangs shut. Your support and participation is everything to us.

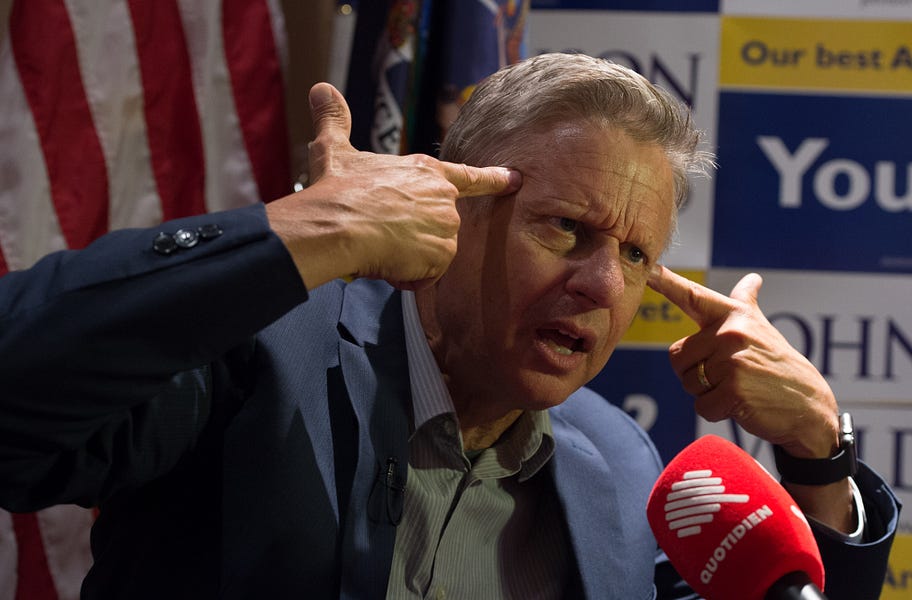

Photograph of Gary Johnson during the 2016 campaign by Bryan R. Smith/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.