The most surreal moment in any interview with one of Donald Trump’s allies in Congress is when they’re asked who won the 2020 election.

A question that any reasonably well-informed 5-year-old could answer without difficulty normally wouldn’t be “the single most important question in American politics today,” as Kevin Williamson called it earlier this year. But Kevin is right. If you want to understand the modern Republican Party in a single exchange, you don’t ask its leaders about abortion or trade or Ukraine. You ask them who won the last presidential race.

It’s become the political equivalent of the riddle of the Sphinx: As in ancient times, woe to those who answer incorrectly.

For Republicans caught between Trump on the one hand and national swing voters on the other, the only safe-ish response is to dodge. That’s what Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton did on Meet the Press this past Sunday when the riddle was put to him. “Joe Biden was elected president in 2020,” he allowed—before quickly adding that “it was an unfair election in many ways” due to states changing their voting laws during the pandemic, Twitter suppressing the Hunter Biden laptop story for a few days, and so on.

So does that mean Trump lost?, he was asked repeatedly. And repeatedly, he wouldn’t say. “Joe Biden was elected president” was as far as he would go.

Cotton dodged more artfully than most Republicans do when answering the riddle, though. The standard response is to dismiss what happened in 2020 as irrelevant because, after all, what’s past is past. Conscientious politicians don’t worry about yesterday; they worry about tomorrow.

That’s how J.D. Vance handled it when Tim Walz posed the riddle to him at their vice presidential debate. “I’m focused on the future,” Vance replied, which wasn’t good enough for Walz (who called it “a damning non-answer”) or, apparently, for Donald Trump. Days later, away from national television cameras, Vance dutifully agreed that his running mate had rightfully won the 2020 election when a voter pressed him on it.

House Speaker Mike Johnson’s eyes were also firmly fixed on the horizon on Sunday when the riddle was presented to him during an interview with ABC News. “You want us to litigate things that happened four years ago when we’re talking about the future,” he complained to host George Stephanopoulos. “We’re not going to talk about what happened in 2020. We’re going to talk about 2024 and how we’re going to solve the problems for the American people.”

“A gotcha game” is how Johnson described the single most important question in American politics today, the one 5-year-olds can answer but some of the most powerful figures in government cannot.

The proper response to this nonsense from Johnson and Vance is a memorable line from William Faulkner, one that applies to all national elections but especially to this one: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Past is prologue.

It’s strange to hear Trump’s cronies, of all people, grumbling about others being too backward-looking.

The modern GOP is obsessed with the past. It’s neck-deep in nostalgia for the “real America” of yore that was lost to demographic change and for the four-year golden age of Trump’s first term that supposedly resurrected it. Trump himself seems to reside culturally in the 1980s, when he was young, vibrant, and still capable of coherent thought.

It’s also the only party since the adoption of the 22nd Amendment to nominate the same man for president in three straight cycles. Offered a variety of talented younger alternatives in this year’s primary who vowed to lead the right into the future, Republican voters preferred to stick with the past.

Had the GOP nominated Ron DeSantis or Nikki Haley for president, the game of dodgeball that Vance and Johnson are playing would be more compelling. Even if they still felt obliged not to offend Trump by answering the riddle of the 2020 election forthrightly, they could credibly say that it no longer mattered because the party had moved on.

Instead, those voters chose to carry that baggage into this cycle by nominating him again. The past isn’t dead; it’s not even past.

As nominee, Trump could have tried to set that baggage down himself by posturing as a changed man. You and I wouldn’t have believed him—he’s incapable of remorse, plainly—but many swing voters would have felt reassured upon seeing him act contrite about how his term as president had ended. Americans dislike the Biden-Harris administration and are trying to get to “yes” on giving Trump a second chance. All he had to do was say, however insincerely, that he realizes now that he lost in 2020 and will be a more responsible leader going forward.

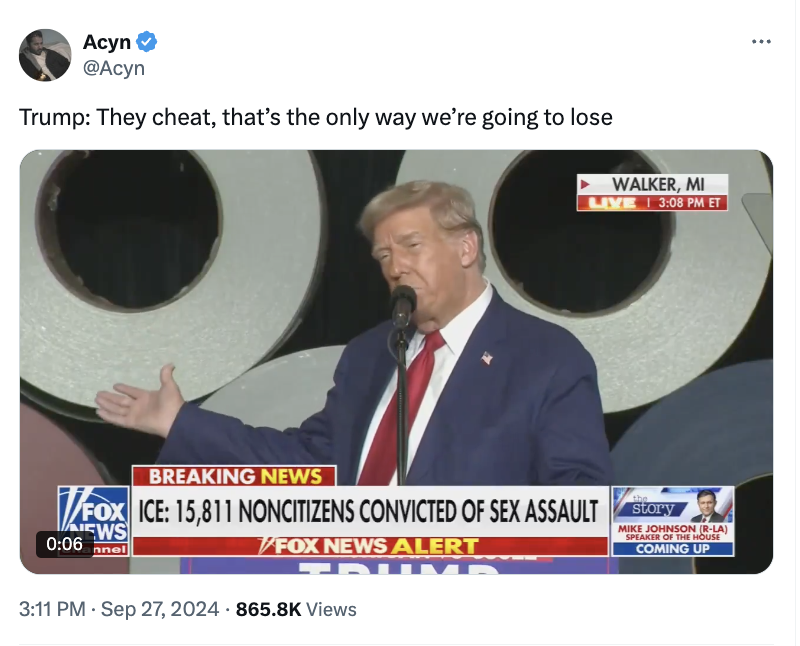

He can’t do it. As recently as last week, he reminded a crowd in Michigan that there’s only one proper answer to the riddle of the Sphinx for Republicans. Verbatim: “We did great in 2016. A lot of people don’t know: We did much better in 2020. We won. We won. We did win. It was a rigged election. It was a rigged election. You have to tell Kamala Harris, that’s why I’m doing it again. If I thought I lost, I wouldn’t be doing this again.”

His monomania about the last election may have caused him to squander his most important advantage in this race, in fact. A New York Times poll released on Tuesday found that Trump now trails for the first time when voters are asked which candidate better represents “change.” Vance and Johnson can babble about the future all they like; for the man at the top of the ballot, it’s 2020 forever. And voters have noticed.

The deeper absurdity in the GOP’s game of dodgeball is how it presupposes that politics follows the same cardinal rule of investing: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. They’d have us believe that there’s nothing very meaningful to be gleaned about how Trump will govern in a second term from the fact that he attempted a coup at the end of his first. Never mind that he’s preparing for another coup attempt, in plain sight, right now.

Turn on any of his rallies lately and you’ll hear him assert that fraud is the only conceivable explanation if he loses next month:

Early voting, mail-in voting, overseas voting: He’s identified each as ripe for cheating. Republicans have begun challenging certain voting procedures in court, correcting the error they made in 2020 by not complaining about the process until after the votes were in. A few months ago Trump’s top campaign adviser, Chris LaCivita, went as far as to warn that the race won’t be over on Election Day, it’ll be over on Inauguration Day. They’re going to do it again.

By renominating Trump, Republican primary voters managed the political equivalent of granting parole to a convicted killer. And the best that chumps like Vance and Johnson can do to defend that decision is whine that those warning that he’ll re-offend aren’t “focused on the future.”

Actually, that gives the two too much credit. Vance and Johnson aren’t just apologists for Trump’s 2020 coup attempt—they’re accomplices.

Mike Johnson was an accessory at the time, aiming to create a legal pretext on January 6 for the House to stop Joe Biden’s electoral votes from being certified. Vance became an accessory after the fact when he faulted Mike Pence for not interfering in the process and leaving the outcome of the election to Congress. And when they’re not busy crying crocodile tears over questions about 2020, they’re preparing to be accessories again. Johnson is already hinting at excuses for not certifying a Harris victory on January 6, 2025, while Vance will surely be Trump’s top mouthpiece on television next month for the new Stop the Steal campaign.

The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past.

The icing on the cake of this bad-faith effort to memory-hole a coup plot is that Trump still faces serious criminal jeopardy for it, a combination of Justice Department foot-dragging in charging him and his own successful legal efforts to delay a trial. It was less than a week ago that the DOJ dropped an updated filing on him that described in gory detail the lengths to which he went to overturn an election. One notable detail: Upon being told on January 6 that his vice president was in danger from the mob he had incited, Trump allegedly replied, “So what?”

If you believe that’s a fact worth knowing about someone who wants to return to the most powerful job in the world, then you necessarily agree that the 2020 election bears on the future, not just the past. Past performance might not be a guarantee of future results—but, in politics at least, it’s a pretty strong predictor.

It’s not (just) about Trump.

The best argument one can make for dropping the subject of who won the 2020 election, I think, is that it’s already priced into Trump’s political stock. He’s a nut; either you know it or you don’t; if you do know it, either you care or you don’t. Wherever you land in that matrix, nothing J.D. Vance or Mike Johnson has to say about it now will change your mind about him. So why keep pressing Republicans on it in interviews?

Because: The riddle of the Sphinx isn’t designed to illuminate something about Trump or the outcome in 2020. Rather, it’s designed to illuminate something about how the culture of the American right has developed in the last four years.

Many Republicans, including Tom Cotton, were appropriately righteous after January 6 in their disgust at what Trump’s propaganda campaign had led to. People who have since become fundraisers for Trump called him a “piece of sh-t f—ing scumbag” at the time and said he should be “disqualified from national office” for his incitement. Four years later, practically the entire party has moved from treating his coup plot as a civic abomination to treating it as not even serious enough to justify preferring his rapidly moderating Democratic opponent in this election.

That demands an explanation, don’t you think? The cultishness of the GOP in its populist incarnation under Trump is the defining political problem of this era. If you’re sitting in front of Tom Cotton, who clearly knows better, how do you not address that problem by asking him about the 2020 election?

It’s not a matter of shaming him. (Although shaming Republicans who are still capable of feeling shame can’t hurt.) It’s a matter of gauging how far the party might be willing to go in Trump’s second term to enable the next civic abomination.

“Voters have a right to know if Trump’s bootlickers can meet the lowest standard of honesty and integrity,” economist Brian Riedl argued, defending the questions to Vance and Johnson about the last election as a useful proxy on that point. “If Trump loses again, we’ll need leaders to stand up to the anti-democratic mob.” A Republican who won’t tell the truth about 2020 for fear of angering the leader almost certainly won’t tell the truth about 2024 if he loses.

And it’s very important to know how many Republicans like that there are in Congress with the next January 6 now on the horizon. We can safely assume that anyone willing to believe, or to pretend to believe, that hacked voting machines produced Joe Biden’s victory in 2020 will believe, or pretend to believe, that illegal immigrants’ ballots produced Kamala Harris’ win in 2024—and will act on it when given the chance on the floors of the House and Senate.

Beyond gauging the amount of authoritarian mischief that might await in the post-election period, though, I think the riddle of the Sphinx is helpful shorthand to convey to normal Americans how conspiratorial the GOP has become.

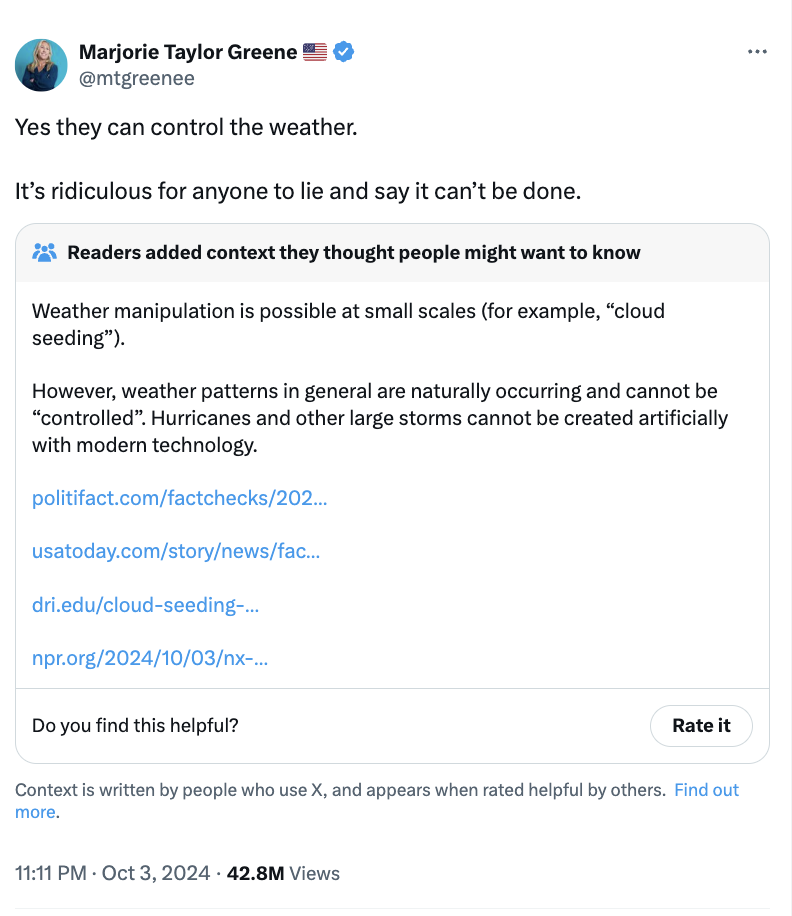

Most voters don’t follow politics closely enough to have noticed that one of the grassroots right’s favorite politicians has taken to tweeting stuff like this lately about hurricanes:

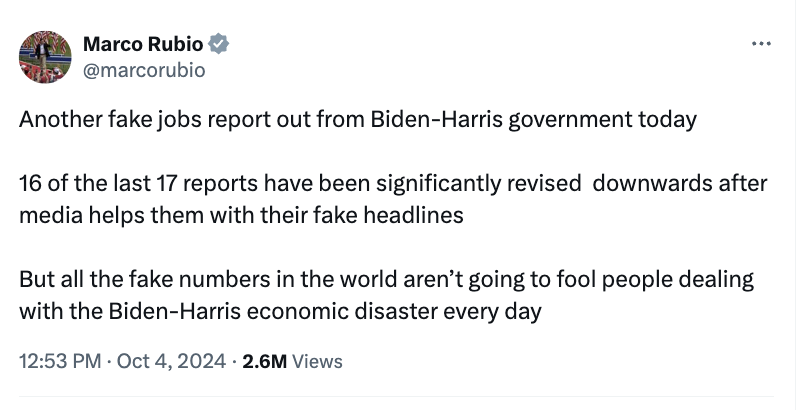

You can scoff if you like and reassure yourself that few Republicans in Congress are as nutty as Marge Greene, but that’s not the point. Michael Wood is correct: “Pick your normie [Republican]: MTG would beat them in any GOP primary, almost anywhere.” Nor is it true that more “respectable” Republican officials are above using conspiracy theories to explain inconvenient realities. Here was Marco Rubio, the great hope of Reaganites circa 2016, doing his best to cope with good economic news last Friday:

Does Rubio think the federal government is controlling hurricanes? Probably not. Does he think Joe Biden won the 2020 election? I … don’t know anymore, although I’m confident he’d look for ways not to say so if he does. If I had the chance to interview him, I’d put the question to him because his answer would supply a fascinating data point in the ongoing civic deterioration of the GOP. Where does Rubio, the “sane Republican,” stand on a controversy that a 5-year-old could resolve?

Swing voters should have an inkling before they go about deciding whether to hand total control of government to this insane party and its more insane leader, no? Journalists can’t devote an entire interview to quizzing right-wing politicians on which conspiracies they do and don’t believe, but they can certainly pose the riddle of the Sphinx and hope that the beads of sweat that appear on their subjects’ foreheads help voters draw the proper conclusion. Namely, that maniacs are in charge of this party and we empower it at our collective peril.

That’s what makes it “the single most important question in American politics today,” as Kevin Williamson said. Politics is ordinarily too complicated for any one query to elicit some essential overriding truth about the stakes of an election but the unusual circumstances of this race have created an exception. We The People watched a civic murder plot play out in front of us four years ago; the suspect is now back on the ballot and half the country is ready to put him in charge of the Army. Under the circumstances, it’d be a dereliction of duty for reporters not to ask his allies, “Was that attempted murder in 2020—or justifiable homicide?”

The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past. It’s prologue.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.