The new Republican trifecta will face some big decisions next year. A large portion of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), passed the last time Republicans controlled the White House and both houses of Congress, will expire at the end of 2025 without congressional action.

Extending these provisions would be expensive. We at the Tax Foundation estimated they would cost $4.2 trillion over the next 10 years, falling to “just” $3.5 trillion after taking economic growth into account. On the other hand, 62 percent of taxpayers would see a tax increase if just the individual tax provisions alone are allowed to expire.

Four trillion dollars is a huge number. But what are the details? And what should policymakers prioritize?

For individuals, rates could rise and filing could be more complicated.

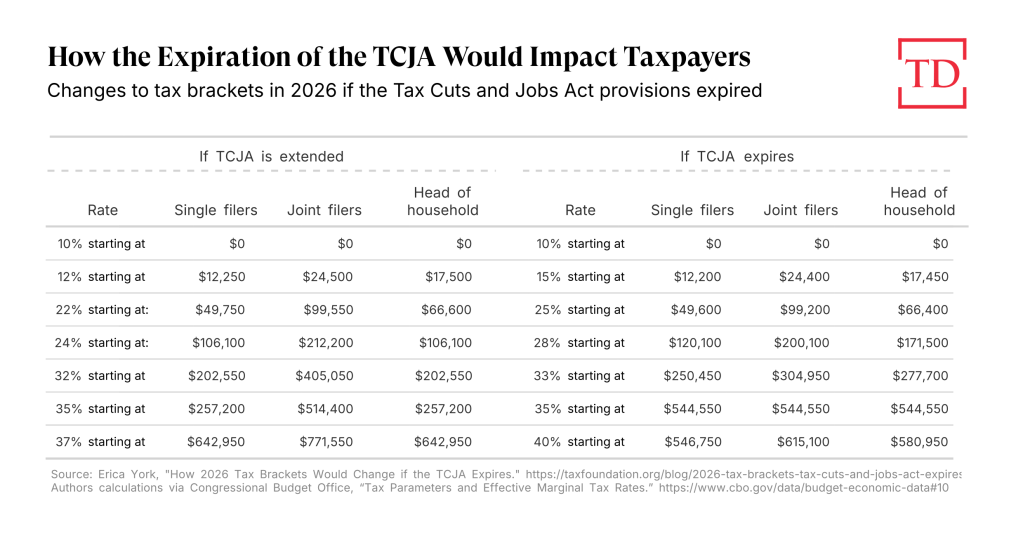

First and foremost, TCJA cut individual tax rates and tweaked the bracket structure. If it’s allowed to expire, tax rates will go back up.

The law reshuffled the benefits of family-related provisions to lower- and middle-income taxpayers, eliminating the personal exemption and effectively replacing it by doubling the child tax credit and roughly doubling the standard deduction.

Expanding the standard deduction simplified the tax code too. In combination with new limits on the mortgage interest deduction and the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the elimination of several miscellaneous itemized deductions, the TCJA pushed more taxpayers toward taking the standard deduction and away from itemizing.

The last notable simplification was limiting eligibility for the alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a ham-fisted way to try to limit the use of certain deductions, and it requires taxpayers to recalculate their tax liability. TCJA raised the exemption threshold, effectively reducing the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT from 5 million in 2017 to just 250,000 in 2018.

For businesses, investment incentives languish.

While some individual taxpayers might be blissfully unaware of the tax changes coming down the pike, businesses large and small have been dealing with the expiration of TCJA provisions for several years now.

TCJA permanently cut the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, but other tax cuts aimed at business investment have started to expire. For example, 100 percent bonus depreciation for equipment investment, which allowed companies to fully deduct the cost of equipment purchases, started phasing out at the beginning of 2023.

Meanwhile, notable tax increases have taken effect as well. Amortization of research and development expenses took effect at the beginning of 2022, requiring companies to spread R&D deductions out over five years (creating a tax penalty for R&D investment). Limits to the deductibility of interest payments have also tightened, and the rates for a handful of reforms to international corporate income are scheduled to increase in 2026.

While individual taxpayers may not see a line item for these investment provisions on their tax returns, R&D amortization and bonus depreciation have a real effect on the paychecks they take home. In the long term, productivity growth drives wage growth, and investment in capital and innovation drives productivity growth. Bonus depreciation was particularly powerful in generating new investment following the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

The other major provision relevant for businesses is the 20 percent deduction for pass-through income, also scheduled to expire at the end of 2025. Around half of business income is earned by pass-through entities: non-corporate businesses taxed under the personal income tax. The pass-through deduction was intended to maintain tax parity between non-corporate and corporate businesses in light of the large corporate rate cut. However, most studies so far suggest that pass-through businesses retain a slight tax advantage over corporations under current law.

Principles for policymakers.

As far as what the “best” tax policy outcome is, the devil is in the details. But lawmakers should keep a few principles in mind.

First, the strongest pro-growth provisions are 100 percent bonus depreciation and expensing for R&D investment. These policies only benefit companies that are making new investments, and accordingly, they have the strongest impact on investment and growth when compared to their revenue costs.

Second, permanent policy is better than temporary policy. Companies and individuals value certainty. What’s more, policymakers often (wrongly) think a temporary policy will end up being extended perpetually. Until recently, it was fairly common practice in Washington for Congress to regularly, albeit temporarily, revive an entire class of temporary tax provisions called “extenders.” The hope with R&D amortization, for example, was to delay it perpetually, but it’s been in effect for almost three years now. In the 2021 American Rescue Plan, progressives pushed for a large, one-year increase in the child tax credit, hoping the program would be popular enough to force policymakers to make a supercharged tax credit permanent. Instead, it expired after one year. In tax policy, one in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Third, the key structural changes of the TCJA are good. Tax policy has two dimensions: the tax rate and the tax base. The TCJA’s reforms (consolidating some family-related provisions, expanding the standard deduction, limiting itemized deductions, further limiting the AMT, and increasing the deductibility of machinery and equipment investment) were good reforms to the income tax base. If fully extending the rate cuts decreases revenue too much, it would still be worthwhile to extend the base reforms. And going even further than the original reforms, like eliminating the state and local tax deduction and mortgage interest deduction, could provide additional revenue to extend more of the rate cuts.

And finally, even if Congress made all of the TCJA permanent, there would still be work to do. The act improved the tax code’s structure, but the reforms were not all-encompassing. The law limited itemized deductions; it did not eliminate them. It (temporarily) eliminated the tax penalty for investment in short-lived assets like equipment, but it kept the tax penalty for long-lived assets like residential housing and commercial structures. The tax code still features a tax penalty against saving.

The way forward.

Even with Republicans controlling the White House, Senate, and House, there will be some major negotiations surrounding what parts of TCJA get extended. Naturally, there is a trade-off between preserving the tax cuts and not further increasing the deficit. But there is also a trade-off involving time: Extending tax cuts for a couple of years costs less than extending them permanently. During the lead-up to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, key decision-makers settled on $1.5 trillion as the maximum deficit impact over the 10-year budget window. That constraint is why many of the tax cuts are expiring in the first place.

Assuming the roughly $3.5 trillion cost of extending the TCJA’s provisions in full would be cost-prohibitive, there are at least a couple of permutations of a possible deal.

One path would extend most or all of the TCJA, but only for a few years, akin to the deal Congress and President Barack Obama agreed to in 2010 when the Bush tax cuts were scheduled to expire. Alternatively, policymakers could make some provisions permanent, and let others expire. This outcome would follow the example of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which made most of the Bush tax cuts permanent, but let the top income tax bracket return to 39.6 percent.

Another path would use the TCJA expirations as an opportunity to further transform the tax code’s structure. Congress could extend all the tax cuts permanently and offset some of those costs by fully eliminating itemized deductions. Lawmakers also could consider other revenue options, like raising the gas tax, or replacing it entirely with a fee based on vehicle miles traveled. Congress could even reintroduce the destination-based cash flow tax idea then-House Speaker Paul Ryan proposed in the 2016 House GOP blueprint for tax reform (arguably TCJA’s first draft), and move to full expensing of all investment, not just equipment and R&D.

Ideally, further structural reforms would make the tax code better. But bad structural change might also be on the menu. On the campaign trail, President-elect Donald Trump has argued for tariffs not only as a strategic tool to protect specific industries, but also a major revenue source. Tariffs have not been a significant source of federal revenue since the mid-20th century. While Trump’s proposed 10 percent and 20 percent universal tariffs could raise somewhere between $2 trillion and $3 trillion over the course of a decade, the idea they could fully replace the federal income tax (which raises over $2 trillion per year) is beyond infeasible

The hope would be that policymakers will approach the TCJA expirations as an opportunity to improve (not worsen) the tax code’s structure, rather than just a looming tax hike they would like to kick down the road for another year.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.