In the midst of the tumultuous presidential election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson penned his views on what America’s military establishment should look like. “I am for relying, for internal defense, on our militia solely, till actual invasion,” he told his correspondent, adding that he strongly opposed “a standing army in times of peace, which may overawe the public sentiment.” As for navies, he dreaded them as well, allowing only “such naval force only as may protect our coasts and harbors.”

Jefferson’s sentiments reflected the prevailing mood of a sizable majority of the country at the dawn of the 19th century: A permanent military force was inherently evil, a tool of tyrants to suppress the people and crush their liberties.

No less a figure than Samuel Adams warned in 1776 that, “A standing army, however necessary it may be at some times, is always dangerous to the liberties of the people.” The reason for this was that, “Soldiers are apt to consider themselves as a body distinct from the rest of the citizens. … Such a power should be watched with a jealous eye.” Citizen militias were the preferred (and, it was assumed, perfectly sufficient) means of defending the nation, while commercial coercion was perceived as a far better means of protecting interests at sea than an expensive, potentially elitist standing navy.

The War of 1812 changed everything. By its conclusion, both the Army and Navy in the United States were firmly entrenched. The government, led by the formerly anti-military Jeffersonian Republicans, had built an expanded apparatus for managing both branches, while the officer corps of each branch had likewise established a greater formal role in oversight of military affairs. The military establishments of the years immediately following the War of 1812 were larger and more self-regulating than virtually anyone in 1800 ever dreamed, or wanted, yet they were also firmly committed to civilian control.

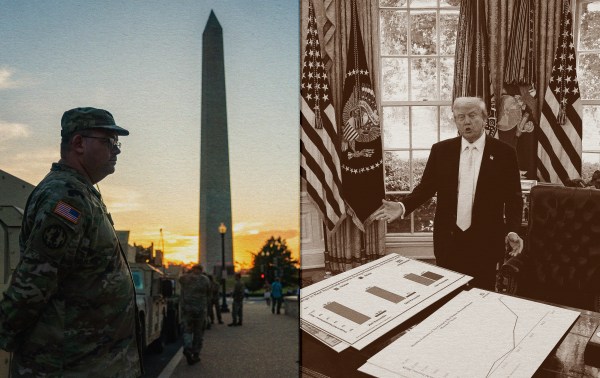

America’s military establishment has come a long way since the early republic. Once derided—if not outright ignored—by the rest of the world as a weak, fractured republic, the United States today has sustained global hegemony for decades with one of the mightiest military forces the world has ever known. And the military remains one of the most trusted institutions in the nation, with even minor diminution of the public’s regard seen as a potential crisis. Americans today take it for granted that our men and women in uniform should strive to be apolitical and remain subordinate to the civilian government.

The effectiveness and high social regard of the military was far from foreordained at the nation’s founding—just the opposite, in fact. The birth of the United States military establishment in the first four decades after independence marked a radical shift in American ideology. In the 21st century, we make the military a tool of partisan politics at our peril. There is ample precedent in American history for distrust of the armed forces, and history shows that the process of building healthy military institutions is perilous and uncertain. A closer look at the early American republic’s fraught process of birthing the military we have today should remind us of the need to safeguard our inheritance.

The Army’s origins.

Opposition to standing armies was deeply rooted in American culture throughout the Colonial era, and the British soldiers who gunned down rowdy protesters at the Boston Massacre and forcibly took up residence on American property served only to solidify that sentiment. Even after the Revolution ended, a great many Americans preferred to remember it as a triumph of citizen-militia taking down professional soldiers. Far from revering the Continental Army, Americans steeped in anti-standing army ideology wanted, at best, to forget the troops who bore the brunt of the war for years in favor of the more politically acceptable militia.

There were, of course, countervailing attitudes. George Washington spent most of the Revolutionary War attempting to build a professional army that could (and eventually did) go toe-to-toe with the British, and he and likeminded Federalists succeeded in securing provisions in the Constitution for a standing army outside the more traditional militia. They even managed to secure constitutional approval for the president to act as commander in chief of nationalized militia when called up by the federal government.

“Americans can rightly admire the wisdom of the republic’s earliest leaders in building a military that can defend American interests without threatening its liberties.”

These provisions were the work of what became the Federalist Party, the faction that rejected Colonial American skepticism toward standing military forces and sought to build a defense apparatus strong enough to protect American interests. Washington, national in focus and shaped by the hardships of maintaining an undersupplied army throughout the war, led the way in this regard. For the father of his country, a proper nation required a proper army.

Washington began his presidency with an army of about 800 men, primarily intended to safeguard the frontier from Native American attacks. Washington ultimately persuaded Congress to expand the size of the federal army after the threat from tribes on the frontier turned into a full-blown crisis, and he even used a militia force to overawe the “Whiskey Rebellion” uprising. But at every step of his administration, the army was a fiercely contested political issue.

Opposing the Federalists were the Democratic-Republicans, later referred to as Jeffersonian Republicans after the party’s unofficial founder, Thomas Jefferson. The Jeffersonians included among their ranks most of the former Anti-Federalists who had opposed the Constitution on the grounds that it too greatly empowered the federal government. The party fiercely defended Americans’ traditional opposition to standing military forces, and grew aghast when Federalists under John Adams and Alexander Hamilton launched a dramatic expansion of the federal army in the late 1790s.

The catalyst for the Federalists greatly overplaying their hand was the undeclared “Quasi War” with France. Fought mainly at sea against French privateers, Federalists, especially Hamilton, raised the specter of a possible French invasion to create a provisional army of more than 4,000 men. In response to pro-French sentiment among Jeffersonian Republicans, Federalists also passed the draconian Alien and Sedition Acts, which horrified civil liberties advocates. Meanwhile, Hamilton aggressively loaded the provisional army with officers loyal to the High Federalists, the most extreme faction of the Federalist Party. His actions appeared to Jefferson and his followers as confirmation of their worst fears for standing armies. Democratic-Republicans across the nation grew increasingly certain that Hamilton meant to use the army to seize power and crush all opposition, a belief that played a major role in Jefferson winning the presidency in the election of 1800.

Republican fears of Hamilton’s provisional army were greatly exaggerated; at no point did the patriotic Hamilton actually entertain Caesaresque dreams, and in any case John Adams was quick to quash the Provisional Army and end the war by diplomatic means. Jefferson nevertheless came into office convinced that his victory had narrowly averted the destruction of the republic at the hands of the High Federalists, and he immediately set about building a thoroughly republican army, one that he could be confident would act as a servant of the people instead of a threat to them. That started, surprisingly enough, with the creation of a military academy at West Point, something that had previously been a longtime Federalist goal. The purpose of the academy was thoroughly Jeffersonian, though: inculcating the correct values of military subordination to civilian control into the nation’s officer corps. In the meantime, Jefferson set about purging the existing officer corps of Hamilton’s men and vetting all future officers for their republican politics.

The Army established.

While the Army’s performance in the War of 1812 left much to be desired, most Americans perceived the war as a great success thanks to Andrew Jackson’s spectacular victory at New Orleans and the fact that the nation had fought Great Britain to a draw. Nevertheless, the end of hostilities demanded a drawdown of forces. President James Madison and his secretary of war, James Monroe, approached the cuts very differently than had their mentor Jefferson. Having learned from the difficulties of taking the field against British forces, Madison and Monroe sought to choose officers for retention based on competence, not politics. As such, they looked to officers themselves to guide the process. As Samuel Watson notes, this was “the first time in American history that the army’s commanders had been asked to systematically evaluate their subordinates,” and the result was “a battle-tested officer corps … eager to pursue military excellence.”

In 1817, Monroe followed Madison into the White House, and he tapped John C. Calhoun as the new secretary of war. Although later infamous for his vigorous states’ rights defense of slavery, at the time Calhoun still counted among the nationalists who sought an effective federal government. His tenure was remarkably successful in expunging the Army’s crippling debt, in no small part through convincing Congress to increase appropriations, but also through vigorously imposing accountability on the officer corps for its use of government funds. Meanwhile, he worked with Congress to improve Army administration, culminating in the 1818 “Act Regulating the Staff of the Army,” a major milestone in systematizing the oversight of the force. Crucially, it expanded the number of General Staff officers and clearly defined their duties, but also based the entire General Staff in the nation’s capital, where the secretary of war could more easily hold them to account. In short, Calhoun’s tenure witnessed an improved apparatus for Army officers to bring their professional expertise to bear in managing the force, while also firmly maintaining civilian oversight.

The Navy’s origins.

The Navy owed its very existence to the Federalist era. After the Revolutionary War, the new nation divested its remaining warships, and for over a decade there was no U.S. Navy at all. George Washington signed the Act to Provide a Naval Armament in 1794 after it passed Congress thanks to overwhelming Federalist support—and in spite of strong pushback from Jeffersonian Republicans. By the time the first U.S. naval vessels launched, John Adams had replaced Washington as commander in chief, and he went on to burnish his standing as one of the fathers of the American Navy. Although created to head off predation of American shipping by the Barbary states of North Africa, the Navy under Adams devoted most of its attention to French privateers during the Quasi War.

For the Navy’s advocates, it was a source of no little alarm when Thomas Jefferson won the presidency in 1800. It was true that many in Jefferson’s party were staunch opponents, regarding the Navy as a waste of money that would inevitably suck the infant republic into Europe’s interminable wars. But Jefferson was far more moderate on the Navy than his party, or even what some of his own statements might have indicated, and the Navy’s existence was never actually in jeopardy. Still, the outgoing Federalist administration understood that there would have to be deep cuts. In an effort to head off the Republicans’ presumed gutting of the budget, it was the Adams administration that crafted and signed the Navy’s first Peace Establishment Act.

The act reduced the Navy in both ships and men, and necessarily slashed the officer corps. Federalist-minded historians have heaped contempt on the act, but the truth is far more nuanced. The dramatic expansion prompted by the Quasi War had included the commissioning of more than a few officers who proved unfit for their posts. The Peace Establishment Act provided a convenient means for getting rid of them and leaving in place a strong corps of competent leaders. As naval historian Christopher McKee concludes, the act was nothing less than “the true foundation of the fully professional officer corps that the United States developed between 1801 and 1812.”

To a greater degree than with the army, the Jefferson administration studiously avoided making naval officer selections a political process. In part, this was unavoidable; the naval service was more likely to attract Federalists, and too many of the best officers shared the views of that party. Some mellowing took place over the course of Jefferson’s tenure though; by the time he left office, famed naval leaders such as Edward Preble and Isaac Hull had drifted into the Republican camp, and even those officers who held on to their Federalist views in private remained impressively apolitical—no doubt partly motivated by the crumbling and eventual implosion of the Federalist Party. Even on the most controversial matter where their service was concerned—the decision to shift emphasis from frigates to smaller, coastal-bound gunboats—the officer corps fell in line with the president’s policies.

The Navy established.

The War of 1812 became the Navy’s golden hour. Even the most rabid proponents of going to war with Britain expected little success at sea; the mighty Royal Navy had only recently obliterated the combined Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar and ruled the waves with unquestioned dominance. Yet a series of shocking victories in single-ship duels elated the American public and killed any lingering vestiges of anti-Navy sentiment. American victories on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain helped secure U.S. territory and contributed significantly to Britain’s decision to end the conflict. The Navy became a symbol of American triumph, the force that had humbled haughty Albion. Of course, the British scored their own share of victories over the course of the war, and by the end a bolstered British blockade of the American coast essentially kept the Navy confined to port, but that mattered little in the heady aftermath of a conflict that Americans touted as their second war for independence.

The postwar boom in support for the Navy led to an expanded fleet and a corresponding expansion in the service’s bureaucratic apparatus. Outgoing Secretary of the Navy William Jones conceded “[it] cannot be denied, that imperfections exist in the civil administration of the naval establishment,” and “a radical change of system” was called for. Jones recommended Congress create a Board of Navy Commissioners to lighten the secretary’s load. Acting on the outgoing secretary’s recommendations, Congress established the board in 1815, to consist of three naval officers at the rank of captain, who would assume a measure of oversight on administrative matters and provide technical expertise.

The board almost immediately triggered a civil-military crisis. While the language in congressional legislation clearly stated that “nothing in this act shall be construed to take from the Secretary his control and direction of the Naval forces of the United States,” the first three commissioners somehow managed to convince themselves that they were to have a role co-equal with the secretary, and they likely planned to sideline him altogether in time and create a naval service led by officers who reported directly to the president. Benjamin Crowninshield, who assumed the post of secretary of the navy after the War of 1812, refused to budge. He first diplomatically, then emphatically, informed the commissioners that their sense of their authority was badly mistaken. The matter passed to President Madison, who ruled decisively in favor of civilian control; “the Board is attached to the office of the Secretary of the Navy, and shall discharge all its ministerial duties, under his superintendence,” Madison wrote in his assessment, assuring Crowninshield that, as a Cabinet officer, “he is to be understood, to speak and to act with the Executive sanction, or in other words, the Executive is presumed to speak and to act through him.”

The Navy commissioners accepted defeat gracefully and assumed their subordinate status under the leadership of the secretary of the navy. That should not, however, indicate that the board lost significance. Over the next three decades, it played a major role in the administration of the service, making major decisions involving personnel, shipbuilding, and supplies. The existence of the board meant that future secretaries of the navy no longer needed substantial maritime backgrounds. Navy secretaries after 1820 became true political appointees, with naval officers themselves providing the technical expertise needed to make the service function effectively.

Conclusion.

This is not to say that the American military was set on a continually upward trajectory. The heady atmosphere after the War of 1812 did not last forever, and within a few years the Panic of 1819 coupled with a generally peaceful international situation left Congress looking for ways to trim costs. In 1821, Congress made deep cuts to the Army and canceled construction on several new naval vessels.

These reductions should not obscure the change that had taken place in America’s military establishment. Viewed with suspicion, and often outright hostility, at the nation’s birth, the army and navy now enjoyed permanent status and widespread acceptance, even celebration, by the American public. They also had expanded bureaucracies to go along with their greater size, and these bureaucracies left ample room for both officer corps to take a significant role in the oversight and management of their respective services. There remained a great gulf between the U.S. military of 1821 and the force that would later defend global hegemony, but the first four decades of the republic were crucial for building a capable, professional, and effective military.

The story of this transformation stands as a beacon and a warning to 21st-century Americans. A full view of the history of the United States shows, clearly, that the nation is far from perfect. Nonetheless, it has its share of notable successes, and Americans can rightly admire the wisdom of the republic’s earliest leaders in building a military that can defend American interests without threatening its liberties. The current stability of our military institutions, however, was neither foreordained nor inviolable. Nor is the gap between America’s military and potential rivals any more insurmountable than the gulf that existed between the infant republic and Great Britain at the dawn of the 19th century. The story of the birth of an American military establishment is both a reminder of the value of building healthy institutions and a call for constant vigilance.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.