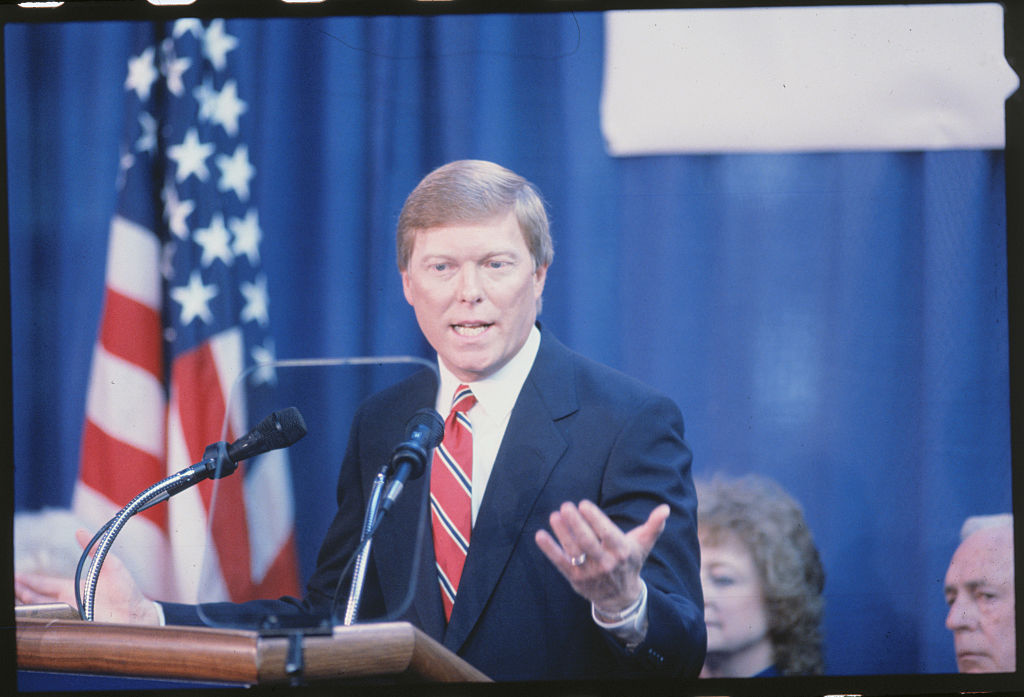

“We will not allow our workers and industries to be displaced by unfair import competition.” If that sounds like Donald Trump, that is because the Republican president and standard-bearer in 2025 is, in essence, a Democrat stuck in the 1980s—and indeed, the line comes from the Democrats’ 1980 platform. The Democrat Trump sounds like is Dick Gephardt, once a very considerable figure in American politics who ran for president twice before retiring to become a bigfoot lobbyist and consultant. He ended up working for DLA Piper and Goldman Sachs—who doesn’t?—but in the 1980s and 1990s, he was the face of center-left trade Luddism, the union goons’ answer to Ross Perot. When the upstart nat-pop right demanded that the GOP abandon “zombie Reaganism,” who knew that what they had in mind was zombie Gephardtism?

Gephardt had more in common with Trump than just being a child of the 1940s: He very badly wanted to be president, and he was (I don’t write “is”; he may have become a better sort of man in his old age) a complete phony. He privately acknowledged that the U.S. trade deficits were only in a very small part driven by trade policies in our country or others. As one economist told the Washington Post at the time: “What aggravates me about Gephardt is that Dick knows better. He could give you the best anti-protectionist speech of anyone on the Hill. But he wants to be president. The Japan-bashing in his amendment is what appeals to labor, and Dick needs labor support for the Democratic nomination.”

Hawkish rhetoric about so-called trade deficits (the term itself is misleading) also gave Reagan-era Democrats a tough-sounding talking point to deploy against Republicans who, then as now, liked to talk a mean fight about budget deficits (which, unlike “trade deficits,” are a thing) while generally making them worse by reducing taxes and doing approximately squat about spending. The “trade deficit” is a much more useful political issue than the actual deficit, because reducing the actual budget deficit means that somebody’s pocket gets lighter—either through higher taxes or lower federal spending or both—while bitching about the inscrutable Oriental with his “iron rice bowl” gives Americans a foreign enemy to blame for any economic disappointment at home while offering General Motors executives an excuse for making spectacularly crappy cars. (If you remember GM cars in the ’80s, oh, goodness: the Chevy Citation, the Buick Skylark, the aptly named Oldsmobile Omega, the ironically named Pontiac Phoenix—incompetent designs incompetently welded together by union guys drunk on the job half the time. Not a golden age for the American automobile.) You sure as hell would rather talk to the median voter about that than about why he needs higher taxes or a smaller Social Security check.

Gephardt’s big idea was the “Gephardt amendment” to the 1987 omnibus trade bill, which would have mandated that U.S. trade partners with large U.S. trade surpluses reduce those surpluses … somehow … by a set amount over a set period of time or have limits (quotas) imposed on their exports to the United States. The result would have been increasing cartelization in exporting nations as governments picked winners in the export-quota lottery (it would have been great for politically connected Japanese firms, less great for politically unconnected ones) and, of course, higher prices and fewer choices for American consumers. Reagan, while congratulating Congress for doing “a remarkable job in watering down or eliminating the most protectionist provisions,” vetoed the bill, anyway, insisting that there was too much protectionism in it still, citing, among other things, a “mistaken effort to revive discredited industrial policy planning through a so-called Council on Competitiveness that will open even more venues for special pleaders.” (Reagan actually vetoed variations of the bill twice over the course of three years.) Reagan was enough of a populist to give in to protectionism from time to time, too, of course—he was more of a libertarian in word than in presidential deed—which was, and has been, about par for the course of muddle-headed American trade policy to this day.

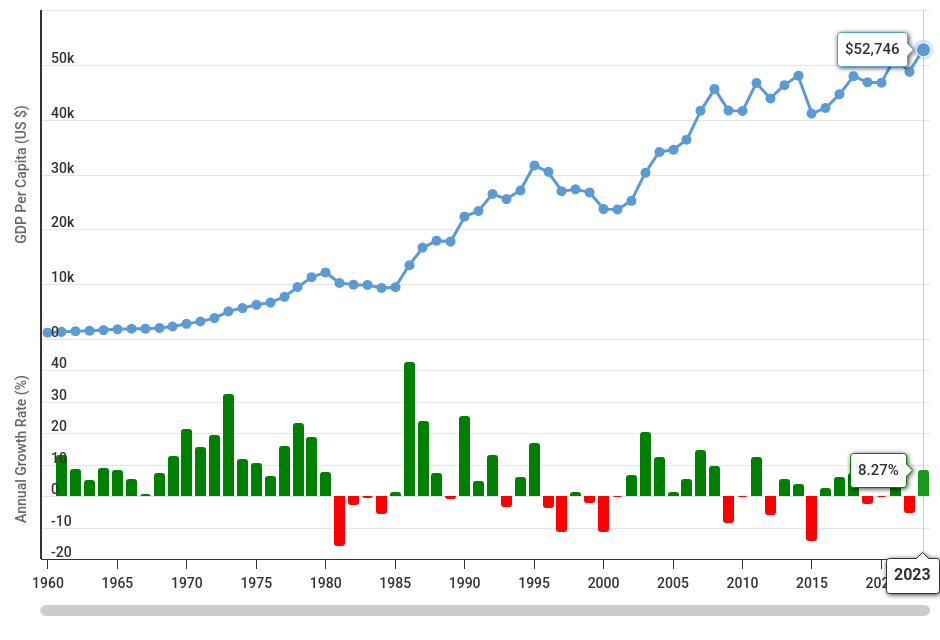

Funny thing about that muddle-headed American trade policy: It doesn’t have very much to do at all with why we have “trade deficits.” Because, counterintuitive though it may seem, the balance of trade in the U.S. economy isn’t a reflection of U.S. trade policy, foreign nations’ trade policy, or anybody else’s trade policy per se, be that good trade policy or bad trade policy, effective or ineffective. The balance of trade is not determined by the (supposed) fact that the U.S. economy is relatively open to trade while our trading partners’ economies are relatively closed. In reality, the United States recently has run trade surpluses with some relatively closed economies (such as Egypt and Ethiopia) as well as with rich and open countries (such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands) while it famously has run trade deficits with closed and hostile countries (such as China) as well as with open and affluent ones (such as Canada). There is much more evidence that U.S. trade balances with these countries are determined by demand for dollar-based investments than by trade policies, which, of course, are radically different from Egypt to the Netherlands to the United Kingdom to China.

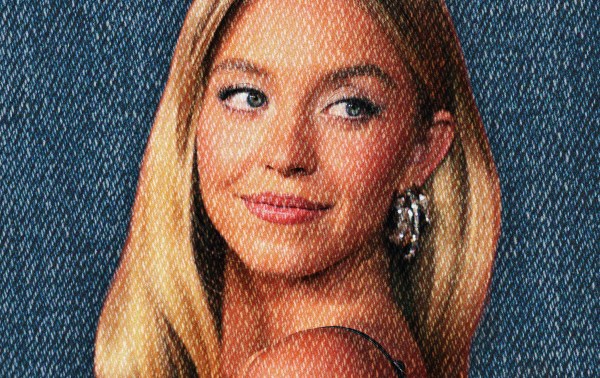

Economists already know this curious fact: The balance of trade is not about trade policy. It is about the fact that countries that trade with one another are bound to have different rates of savings and investment, which will as a matter of mathematical necessity show up as “trade deficits” in the case of relatively high-investment nations, because the “trade deficit” is the flip side of the capital surplus. There is a lot of opportunity for investment in the United States and, hence, a hearty demand for capital, a demand that is so expansive that it cannot be satisfied by domestic savings. So capital flows into U.S.-based investments from abroad. A dollar that is invested in Apple shares or Treasury bills is a dollar that cannot be used to purchase a pair of (e.g.) U.S.-made jeans. (Contrary to what you may have heard, the manufacture of clothing in the United States is still very much a going concern; it does tend to be better, higher-priced, higher-margin stuff rather than the cheap high-volume stuff you can get at Walmart—poor, poor, pitiful us. But you know who is grateful for that cheap imported stuff? Poor people who actually go to work in boots and can’t afford to pay the better part of a grand or more for a pair of really nice work boots.) Daniel Griswold explained in a very useful paper way back when:

The necessary balance between the current account and the capital account implies a direct connection between the trade balance on the one hand and the savings and investment balance on the other. That relationship is captured in the simple formula:

Savings — Investment = Exports — Imports

Thus, a nation that saves more than it invests, such as Japan, will export its excess savings in the form of net foreign investment. In other words, it must run a capital account deficit. The money sent abroad as investment will return to the country to purchase exports in excess of what the country imports, creating a corresponding trade surplus. A nation that invests more than it saves–the United States, for example–must import capital from abroad. In other words, it must run a capital account surplus. The imported capital allows the nation’s citizens to consume more goods and services than they produce, importing the difference through a trade deficit.

In 1996 Americans invested $1,117 billion privately and another $224 billion through government, for a total of $1,341 billion in gross domestic investment. National savings, however, fell short of that amount, requiring Americans to import a net $133 billion in capital. That same year Americans paid $1,238 billion to the rest of the world for imports of goods and services, net transfer payments, and income on foreign investments in the United States, while receiving $1,105 billion for exports and investment income. The result was a current account deficit of $133 billion, equal to the net inflow of foreign capital.

As Griswold notes, the strong dollar is more a cause of capital inflows than a result of them. And that strong dollar tends to increase trade deficits by making U.S. exports to the world relatively expensive and imported foreign goods relatively cheap for dollar-holding Americans:

The transmission belt that links the capital and current accounts is the exchange rate. As more net investment flows into a country, demand rises for the dollars needed to buy U.S. assets. As the dollar grows stronger relative to other currencies, U.S. goods and services become more expensive to foreign consumers, reducing demand, while imports become more affordable to Americans. Falling exports and rising imports adjust the trade balance until it matches the net inflow of capital. In effect, foreign investors will outbid foreign consumers for limited U.S. dollars until the investors satisfy their demand for U.S. assets. Of course, most day-to-day currency transactions are not directly related to trade, but demand for U.S. goods, services, and assets affects demand for the dollars needed to buy them, thus influencing the value of the dollar in global currency markets.

Griswold offers a real-world example:

Germany in the early 1990s offers a case study of how this mechanism works. West Germans routinely ran large current account (and trade) surpluses in the 1980s, but between 1990 and 1991 Germany’s current account flipped from a surplus of 3.2 percent of gross domestic product to a deficit of 1.0 percent. The reason for the reversal was not that German manufacturers suddenly lost their legendary efficiency, or that Germany’s trading partners imposed new and unfair trade barriers on the night of December 31, 1990. What caused the switch was the huge increase in domestic investment needed to rebuild formerly communist eastern Germany. An increase in domestic investment repatriated a huge amount of German savings that had been flowing abroad, thus reducing the amount of German marks in the foreign currency markets and raising their value relative to other currencies. The stronger mark, in turn, raised the price of German exports and lowered the price of imports, evaporating Germany’s trade surplus.

So, Germany must have been immiserated by that evaporation of its trade surplus, right? Of course not. Investment turns out to be really, really good for an economy, and Germany’s real GDP per capita today is well more than twice what it was in the 1990s.

Is the story more complicated? Of course it is! And if you really want to dig into it, you could do yourself a favor by consulting this policy brief from the Peterson Institute’s Maurice Obstfeld, who incorporates some additional factors such as the millennial housing boom’s contributions to American consumption, the role (or supposed role) of capital inflows in that housing boom, the effects of credit and interest rates, etc.

What you will not find is very many people who know anything about this who believe that the trade deficit is a problem created by unfair trade practices on the part of our trading partners and insufficient paternalism in Washington. But, of course, we haven’t elected somebody who knows anything about that as president. And to the extent that the people around him do know something about it, they are in the main obliged to pretend to be as ignorant as Trump is.

And Furthermore …

From Obstfeld:

[T]rade partners’ commercial policies are an unlikely explanation for US trade deficits, the roots of which are primarily macroeconomic. The global saving glut hypothesis, however, has value in explaining the initial expansion of the US external deficit between 1998 and 2001, although gaps in balance of payments data obstruct a full assessment. The hypothesis is much less applicable to the further expansion of the US deficit afterward—the period of most rapid US housing appreciation, but also of more rapid growth in US imports from China.

In those years, a widening external deficit was substantially driven by domestic US factors, notably the housing boom, which itself was not caused primarily by net capital inflows. The major causal factor was the ease of financial conditions in the United States in the form of relaxed borrowing constraints facilitated by financial innovation. Lower interest rates likely played some role as well, but possibly a subsidiary one. For the most part, foreign capital did not push in during 2002−06, it was pulled in. A strong indication of the changed dynamic was the dollar’s very different behavior over 1997−2001, when it appreciated, as compared with 2002−06, when it weakened.

The latter period illustrates that a weaker dollar today would not necessarily be associated with a reduced US trade deficit. The policies pursued to weaken the dollar would be all-important. They would not necessarily reduce the deficit and might inflict considerable collateral damage.

Both major US political parties have become more hostile to international trade in this millennium, viewing trade deficits as a cause of deindustrialization and tariffs or other trade restrictions as potential antidotes. But the ills that are blamed on trade (as well as other ills) owe in large part to purely domestic policy failures that no degree of trade restriction can repair.

“Failures that no degree of trade restriction can repair” sounds like the policy CV of a lot of Trump’s new Cabinet members.

And Furtherermore …

Also: It seems to me that the people who moan about the so-called trade deficit are also the people I hear fretting about the possibility that the dollar will lose its role as the world’s “reserve currency.” It never seems to occur to them that it is those trade deficits that enable the dollar’s use in reserves; if China were running a trade deficit with the United States instead of the other way around, it wouldn’t have a lot of dollars to put in its reserves.

Worldwide demand for dollars is just astounding. According to a 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service, the dollar accounts for nearly 90 percent of daily worldwide foreign exchange turnover ($6.6 trillion at the time). How big a sum are we talking about in practical terms? Says the report: “On a daily basis, the value of global foreign exchange transactions eclipses the total global value of economic output and the value of all traded stocks and bonds.”

And Furthererermore …

I am very fond of David French and Sarah Isgur, and I like listening to Advisory Opinions. But I did yell things at my car stereo that cannot be printed here when listening to them discuss trade on a recent episode. No, we did not “ship jobs overseas” and hollow out U.S. manufacturing with trade. And no, we would not be better off—economically, politically, or spiritually—if we somehow managed to artificially raise the price of clothing and thereby artificially lower Americans’ standards of living, i.e. if we made Americans poor for no goddamned reason.

Lawyers.

In Other News …

After lo these many years, Amazon has decided that Ryan Anderson can sell his book on their platform. I wonder what happened.

Sex and the Generation X Woman

Here is an example of a really well-done article of a kind that is very difficult to write well. Writing in the New York Times, Mireille Silcoff explores why women well into middle age are having a better time of it sexually than are many younger women.

The sexual Perennials of this generation do not fit neatly into any of the well-trodden archetypes of older women, like the cougar or the MILF — these degrading male-gaze notions of women precariously perched on the brink of undesirability. Pop culture is only now beginning to create new symbols of them, while those of the past feel silly or peculiar. (In the 1980s, Blanche Devereaux of “The Golden Girls” was often portrayed as a swooning, silk-draped clown for merely having a libido; at the start of that series she was supposed to be around 53, which is two years younger than Jennifer Lopez is now.) The Perennial’s vibe is not about finding a pocket of succor after the sun of youth has set. It is, rather, a power stance — a matter of caring less and less about such expectations the older you get.

Good point about Blanche. Related: Carroll O’Connor was only 46 when he took on the role of Archie Bunker. Sobering: Abe Vigoda was younger than I am today when he made The Godfather. Related in a different way: The actress who played Blanche Devereaux is known as Rue McClanahan, but her given name was the much more vivid Eddi-Rue McClanahan, the belle of Healdton, Oklahoma. She dropped the “Eddi” part because she kept getting mistaken for a man—she once got notice that she was about to be drafted into the military.

Words About Words

There’s nothing exactly wrong with Philip Hamburger’s anti-D. of Ed. essay in the Wall Street Journal, but the headline—“The Education Department and the KKK: Nativists originally led the charge for centralized education”—and the general plan of the argument is an example of an association fallacy, a kind of guilt-by-association form of political argument. You know: “Hitler was a vegetarian, ergo …” (Yes, I know about Hitler’s supposed vegetarianism. Don’t write me about it.) You see this in all sorts of daft contexts, and, often, the association is fictitious: You may have heard that we have a Second Amendment because slaveholders wanted to make sure they could put down rebellions and have well-armed slave patrols, which is not actually how we ended up having a Second Amendment. To take a different example: It is true that there was an uptick in private education in some places following the racial integration of public schools, but the notion that this makes modern school-choice initiatives racist is pure poppycock. (Setting aside even the fact that many such programs would mainly benefit, and are designed to benefit, black families.) There might be a good reason for a federal department of education (I don’t think we need one; but, then again, I don’t really think we need public schools as currently constituted, either) or there might not, but whether early supporters of centralization were nativist knuckleheads doesn’t tell us much about that.

Hamburger isn’t wrong, let me repeat: In education, as in much else, the homogenizing progressive tendency was very much intensified by dread and disgust directed at new immigrants and their strange ways and their supposedly primitive—and anti-democratic—Catholicism. The Blaine Amendments and Prohibition and Planned Parenthood-style eugenics all are crabs cooked in the same pot. But that doesn’t provide us with very much information that is useful or relevant to current debates about public schools or drug abuse or abortion.

In Other Wordiness …

I’ve been reading up on William F. Buckley Jr. for various reasons, and I came across Nora Ephron’s absolutely appalling review of his book Overdrive for the New York Times, which is snootier than anything Buckley ever wrote, harpsicords and yachts be damned. And it even manages to climax with an ethnic slur:

A boy born to a small oil fortune grows up to be a man with three homes, five in help, a wife on the best-dressed list and the secure belief that even his preference in peanut butter will be of interest to his fans. His attitude toward life is so cheerful and good-natured—and what’s more, he’s right about the peanut butter—that it seems almost churlish to point out that it is possible to spend too much time in a limousine. The English used to say, give an Irishman a horse and he’ll vote Tory, but never mind.

It was, of course, those Irish Catholics that a lot of the nativists behind the Education Department were worried about. But they probably did not mean the Buckleys.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

In one of the week’s least surprising stories, the Wall Street Journal found that corporate DEI programs have had basically no effect on the composition of businesses’ work forces. As a practical matter, getting rid of them will amount to approximately squat as well. But if what you’re interested in is symbolic Kulturkampf stuff, then this all matters a great deal. Nah, it’s all good, bros—it’s not like we have any real stuff to deal with.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.