Poetry has been an essential part of many countries’ popular culture for centuries. Italy, Russia, Iran, Chile, Poland, and Nicaragua are good examples, to name just a few. In these places, professors do not have a monopoly on poetry. Cab drivers, accountants, and salespeople will, often with very little provocation, recite a poem from memory. The United Arab Emirates and Qatar even host lucrative poetry competitions televised in the style of American Idol.

This kind of enthusiasm invariably starts early. When I was 4 years old, my mother would take me out to the front lawn and read poetry to me—mostly A.A. Milne and Dr. Seuss—under our big old tree. A brutal fourth grade teacher almost killed my interest in poetry with a forced march through her haiku unit, but the next year a teacher near retirement, Miss McDermott, made me memorize my first poem and spurred me to write a poem that years later would appear in my high school’s literary journal. Her encouragement was reinforced by a kind children’s librarian, who gave me books to read and eased me into the adult library.

This support was not new or unusual. Parents and teachers in the 19th century often considered poetry a vehicle for expressing pride in their country and its form of government, and they increasingly taught their children the pleasures of poetry. Soon, America had its first great American poet, Edgar Allan Poe, whose poem “The Raven” is still so popular that it was the subject of a Simpsons episode. By the time of Poe’s mysterious death, Americans were embracing poetry both for the joy of it and as a means of self-improvement that might help them climb social and economic ladders. Although colleges and universities usually did not teach contemporary poetry, most newspapers and magazines included room for poems.

By the middle of the 19th century, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman were infusing their work with our growing sense that there was something unique and important about “the American experiment.” Longfellow generally followed British practices for rhyme and meter, but contributed to the cause by making episodes of American history the stuff of epic poetry. Even today, it is hard on Patriots’ Day in Boston to avoid Longfellow’s invitation to “hear / about the midnight ride of Paul Revere.”

Whitman, on the other hand, took a very different path by challenging longstanding notions about what poetry should discuss and how it should be written. Although one of Whitman’s most beloved poems, an elegy for Abraham Lincoln called “O Captain, My Captain,” uses meter and rhyme, most of Whitman’s poetry avoids traditional prosody; many of his poems run long, with meandering, unrhymed lines that echo the cadences of the King James Bible (but without the Christianity). He also opened up risky topics, including pantheism, gay love, and blue-collar identity.

Poetry in America’s past played a distinct role in communicating with the people. For example, poetry influenced the movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, which gained momentum after World War I and in which black intellectuals centered in New York City saw an opportunity to plead their cases for civil rights through the arts. In 1919, a very young Claude McKay published the Shakespearian sonnet “If We Must Die,” and in 1921, a young Langston Hughes published “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” These poems and others in the same vein by other Harlem Renaissance poets helped to unify black Americans and to persuade many white Americans that equal treatment for black Americans was overdue. Beyond Harlem, the mid-20th-century American poets, particularly such light verse poets as Ogden Nash, Phyllis McGinley, and Dorothy Parker, were celebrities—Nash was a game show panelist, and Dylan Thomas’ tours of America had a rock-star quality before there were rock stars.

The people-forward sentiments of this poetry, however, suffered serious blows later on in the 20th century, most clearly by the poet and critic Ezra Pound. He filled his work and public comments, particularly his radio broadcasts for Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in World War II, with vicious antisemitism and crackpot conspiracy theories, and he mistranslated some of the most splendid classical Chinese poems ever written. Perhaps most damaging was his injunction to “make it new,” which offered an avenue for poets to take the easy road of producing impenetrable masses of words and justify it with the excuse of novelty.

But as much as professional poets damaged the popular conception of poetry in America, academia’s move into creative writing turned out to be the death knell. Throughout the 1960s, there were only a few universities offering a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree in poetry. In a boom time filled with would-be poets that followed, these programs brought in tuition, federal subsidies, and cheap labor for undergraduate English classes. It became a no-brainer not just to have an MFA program in creative writing, but to have as big a program as possible.

In order to fill all these newly created seats, colleges and universities had no choice but to water down their programs. Writing in form and meter takes time to learn, and many of the best formal poets only write a few poems a year. Today’s requirements for MFA students make it clear that volume has become an unfortunate proxy for productivity, and it seems that pretty much anything slapped on paper will satisfy graduation requirements as long as it conforms to institutional politics. Pound’s “Make it new” continued as the unofficial motto, and MFA professors began mocking traditional prosody as outdated—or even a tool of oppression. Literary journals, usually run by young people fresh from MFA programs, gradually followed suit.

In essence, MFA programs built a wall between American poets and the public. Their graduates write for other poets in their guild, as they have been trained to do, and even members of the guild do not seem excited about what they are reading. If you ask a group of 10 professors at MFA programs to agree on five contemporary poets under the age of 50 that most impress them, then ask them to recite a single line from each of those poets, they almost surely could not do it. In other words, we have lost something important—today’s American poets mostly write in ways that do not connect broadly with the American public.

We have a small number of poets doing wonderful work that is not embedded in our culture, and we have poets whose work has connected deeply with some particular constituency. But mostly, we have professional poets who do not think it is a problem that their work bores and frustrates Americans who love poetry.

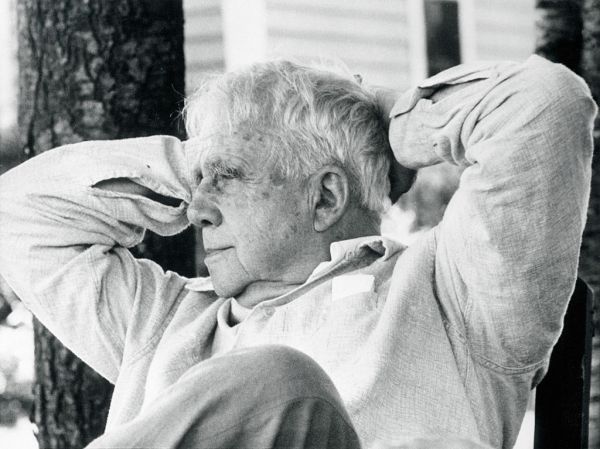

To understand what we have lost, you might look at Robert Frost, who was a household name for decades before his death.

Though scholars rarely view Frost as a “confessional” poet, he often explored his own psyche in ways that were rare before his time, as in his haunting “Acquainted With the Night,” which seems simple on the surface, but is technically brilliant in that it skillfully combines the sonnet with the terza rima form of Dante. He also had a genius for putting commonplace rural New England scenes into a more universal context, as in “Mending Wall,” which gave us the opening line “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” and later, the oft-quoted counterargument: “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Other poets have become national poets in other nations; the unique role of Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney in Ireland comes to mind first, but there are many other examples as well. America has not had such a poet since Frost, and no MFA program has produced a poet as great as Frost, or as great as other such 20th-century giants as W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.H. Auden, Richard Wilbur, or Edna St. Vincent Millay. We do have a few living poets, such as Rhina Espaillat and Dana Gioia, whose work could play that role for us. Regrettably, though, our political and literary cultures refuse to embrace, at least en masse, these great American poets and their work. We would be better off as a nation if our cultural gatekeepers were more open to the rich poetic traditions of their own country.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.