During this critical moment when there are looming shortages in medical supplies, especially ventilators, policymakers and executives are drawing inspiration from World War II-era wartime production. On Tuesday, the Trump administration invoked the Defense Production Act to speed the procurement of COVID-19 test kits. Auto executives like GM’s Mary Barra and Tesla’s Elon Musk are repurposing their factories to fight the ventilator shortage and reports abound of smaller firms finding ways to pitch in.

For low tech items, the private sector has responded by quickly shifting production from non-essential products, like whiskey and apparel, to essential ones, like hand sanitizer and face masks. But, for more complex medical devices, like ventilators, industry experts warn that policymakers and the public should be cautious in placing too much hope in the hands of companies inexperienced with medical device production. Ventilators are complex, expensive machines that rely on dedicated global supply chains. In normal times, getting regulatory approval for new machines requires years of testing to ensure reliability and safety.

Revisiting the history of airframe production during the early 1940s is instructive in helping us understand what would be required to ramp up ventilator production to levels experts predict could be demanded by the public health crisis. In May 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for the manufacture of at least 50,000 new planes per year, up from annual production of around 6,000 in 1939. Responding to the president’s call, in January 1941 Ford Motor Company’s Edsel Ford and Charles Sorenson visited the plant of Consolidated Aircraft, the designer of the B-24 bomber, to see how Ford could help. Sorenson concluded, audaciously, that Ford could transform the production of airframes from traditional, craft methods to modern assembly line methods and, in the process, increase the rate of production from one bomber a day to one bomber an hour.

Sorenson’s prediction was eventually proven right. By mid-1944, Ford indeed was producing one B-24 per hour as promised. However, it took nearly 20 months from the time Ford won the military contract in February 1941 until it produced its first plane at its new plant in Willow Run, Michigan. And, even as late as February 1944, manufacturing at Consolidated Vultee—Consolidated Aircraft merged with Vultee Aircraft in 1941—was more efficient than Ford’s assembly line. By the time that the Willow Run plant was operating at peak capacity, wartime demand for new bombers was already on the decline.

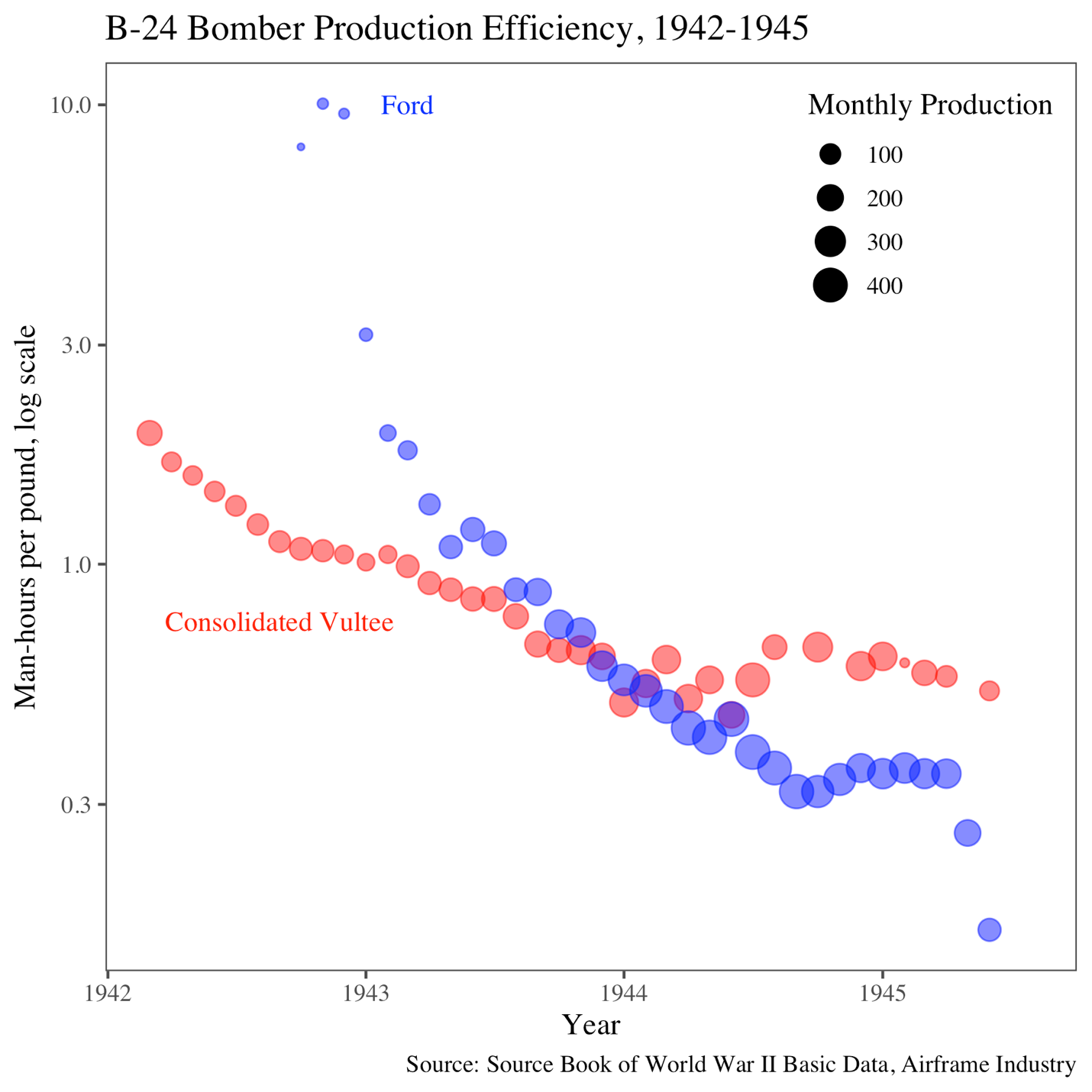

Ford’s experience building aircraft on an assembly line is an illustration of the tradeoffs policymakers face when deciding how best to leverage private industry to address shortages during a national emergency. In the graph below, I plot the number of man hours required to produce a pound of airframe for Ford (in blue) and Consolidated Vultee (in red). (Each B-24 bomber weighed approximately 23,000 pounds.) By the second half of 1944, Ford was significantly outproducing Consolidated Vultee in terms of both volume and efficiency. But, Consolidated-Vultee began production six months before Ford and remained more efficient for a full two years before Ford caught up.

The lesson to take away from Ford’s experience building bombers at Willow Run is that firms building a new product eventually become more efficient as they learn-by-doing, but there is a learning curve. Therefore, the fastest way to immediately ramp up production is to rely on the experienced producers who have the necessary knowledge and routines to scale quickly and reliably.

For ventilators, firms like Medtronic and GE Healthcare are our best bet for ramping up supply to meet the current shortage. Building as many ventilators as we can as fast as we can is best achieved by maximizing existing capacity and using well-understood production and assembly methods.

However, medical device manufacturers have never before contemplated needing to manufacture ventilators at such scale. Manufacturers experienced in mass-producing advanced machinery have a comparative advantage in designing fast, cheap, and reliable production and distribution systems. Strategic partnerships between medical device makers with detailed knowledge of ventilator technology and companies with extensive production engineering experience could be especially fruitful.

It could take months or even years for a GM- or Tesla-designed ventilator to become a viable alternative. At best, the healthcare system will be better prepared in the event of a second infection wave. The extraordinary measures being taken to protect public health today will be harder to sustain in the future when the economy and healthcare system are still reeling from the first wave of COVID-19 infections.

But even if it takes years for a new ventilators design to reach peak production, there are good reasons for the federal government to support these efforts, starting today. The oversupply of medical equipment can be stored to make sure that the nation is better prepared for a future pandemic or exported to other countries facing ventilator shortages. Further, having more U.S. manufacturers with experience producing critical medical devices can only strengthen the resilience of our healthcare system against future crises.

However, getting automakers and other large manufacturers to undertake the investment to reconfigure factories in order to produce a lower-cost and quicker-to-build ventilator is going to require a long-term commitment by the federal government. Just as Ford’s investment in Willow Run required assurance that the government would buy the planes, even well-intentioned CEOs deserve assurance that the government will fill a gap in market demand if the pandemic has ended by the time they get production up and running. But, given the extraordinary lengths to which the government has already gone to support public health and provide economic relief, spending the extra billions to vastly expand the current supply of ventilators is a prudent insurance policy and a worthwhile bet on the ingenuity of American business.

Scott Ganz is a research fellow in economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

Photograph of B-24s being built at Ford’s Willow Run facility from the Bettman Archive/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.