Zuhurullah Sharifi gets the same response every day when he checks his application to change his immigration status: under review.

Sharifi and his family are among the tens of thousands of Afghans granted humanitarian parole during the chaotic U.S. withdrawal and subsequent Taliban takeover of his country two years ago. Out of approximately 77,000 Afghans granted humanitarian parole, only about 10 percent—8,127—have obtained a more permanent immigration status from the United States’ backlogged immigration system, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). As of May, the latest month for which numbers are available, 2,527 Afghans had been approved for asylum, while 5,600 were approved for green cards.

Being on humanitarian parole has allowed this group of Afghans to live and work in the United States since moving here. But it expires at the end of September, leaving their legal authorization to work in doubt.

“I don’t think anyone’s proposing removing people from the country,” Matthew Soerens with the refugee agency World Relief tells The Dispatch, noting that the United States does not recognize the Taliban as a legitimate government and has no diplomatic relations.

What’s more likely is that if people aren’t granted a renewal of their parole status on a timely basis, they’ll start to lose their work permits. Without those, their jobs, and potentially housing and other hard-won stability, would be in jeopardy. Soerens adds there is also the risk that, as their statuses lapse, “they become undocumented immigrants.”

“It’s particularly crazy that we potentially do that to people who we brought here—like our government brought here—because they, in many cases, served the U.S. military or in some other way they were at risk because of their association with the United States,” Soerens says.

Humanitarian parole, which offers no pathway to a permanent immigration status, is a classification granted by the president to allow people to come to the United States due to dire humanitarian reasons and live in the country for up to two years. Parolees can fill out an asylum application or apply to the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program (which confers a lawful permanent resident, or a green card, status). After one year, those granted asylum can apply for a lawful permanent resident status. After five years, eligible lawful permanent residents can apply to become U.S. citizens.

But the United States’ immigration system faces a yearslong backlog.

Two years ago while still in Afghanistan, Sharifi sought SIV status—for which he is still waiting. But with the fall of Kabul he was granted humanitarian parole and he and his family were airlifted out of the country. And he’s one of the fortunate ones. About 152,000 SIV applicants, often including people who worked with the military or for another U.S.-backed organizations, still remain in Afghanistan. Many of them are hiding from the Taliban.

The answer to Sharifi and other Afghans’ plight lies with Congress. It was the legislative branch that intervened to allow past groups of humanitarian parole recipients, such as Hungarians and Cubans fleeing oppressive communist regimes in the 20th century, to adjust their status.

A coalition of bipartisan lawmakers has reintroduced the Afghan Adjustment Act, legislation that would create a pathway to permanent residency for Afghan humanitarian parole recipients. But the bill failed to pass Congress last year. In the Senate, it didn’t make it into the end of the year omnibus spending bill or the National Defense Authorization Act. Democrats and some advocacy groups blamed Republicans: Sen. Chuck Grassley and some others wanted stiffer vetting protocols (even though the bill includes another round of immigration vetting for anyone seeking permanent residency).

“We owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the Afghan people for the ways they supported U.S. forces for almost 20 years, often at great personal risk, and this bill is a first step toward keeping our word as a nation and honoring that debt,” Sen. Chris Coons, a Delaware Democrat and co-sponsor of the Afghan Adjustment Act, tells The Dispatch in a statement. He says he’s doing what he can to “enact this legislation as soon as possible,” but its fate in the current Congress is uncertain.

Still, support for the bill continues to grow among a variety of organizations, including veterans groups, and religious and humanitarian groups.

Helal Messomi, Afghan policy adviser for Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, tells The Dispatch the Afghan parolees she knows want to settle in—and give back. “They’ve supported the United States Army, United States consulates and embassies in Afghanistan for 20 years, despite all the difficulties they were facing,” she explains. “Imagine what they can do inside the United States with definite status.”

“To be honest, I don’t want to leave my country,” Sharifi says. “For everybody, it’s very difficult to leave their home country and be living as a refugee in another country.”

But returning to a country ruled by the Taliban isn’t an option.

In January 2020, the Taliban gained control of most of the Badakhshan province, where Sharifi lived. Soon after, Taliban members began sending him and other family members threatening text messages every couple of days. His family would pay for his mistakes, they told him.Those mistakes? Working for an international design and construction company headquartered in Virginia.

Sharifi went into hiding: He slept in different houses each night to evade the Taliban. He was desperate to leave and to get his wife Shakiba and four children (ranging from ages 9 to 3) to safety. By the end of August 2021, they became some of the fortunate few who made it out of the Kabul airport. That involved camping out for days in the airport—and withstanding more Taliban intimidation.

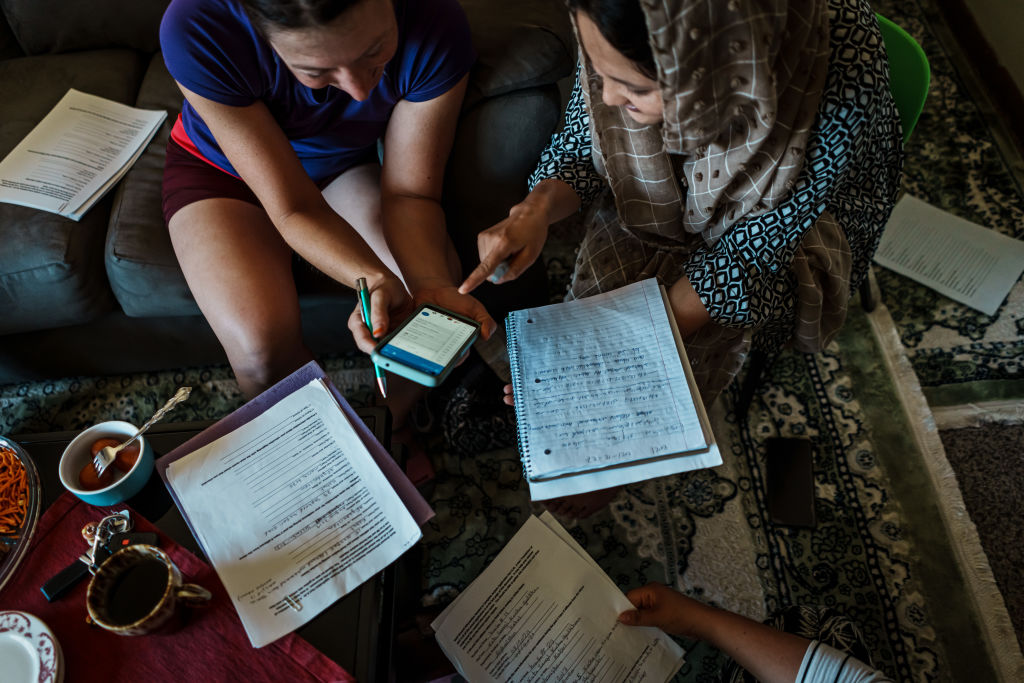

They made it to Virginia before heading to Fort McCoy in Wisconsin, where they spent three months undergoing background checks, biometric screenings, and other procedures. They are now resettled in North Carolina, where Sharifi works as a finance coordinator with Pepsi. But life is far from settled.

“Once the United States decided to bring them here, they have put them in a situation—they are not getting any sort of support,” Messomi said. “There’s no way to go back to Afghanistan. I’m more than sure they will not make the first hour in Afghanistan.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.