WASHINGTON COUNTY, Wisconsin—The Washington County Fair is a prime opportunity for politicians on the stump ahead of the state’s August 9 primaries.

With a backdrop of the sounds of chattering families, bustling food vendors, and live music, and the smells of deep frying meat, powdered sugar, and perspiration, candidates for state and local offices turn out to shake the hands of as many potential voters as possible and hear what is on their minds.

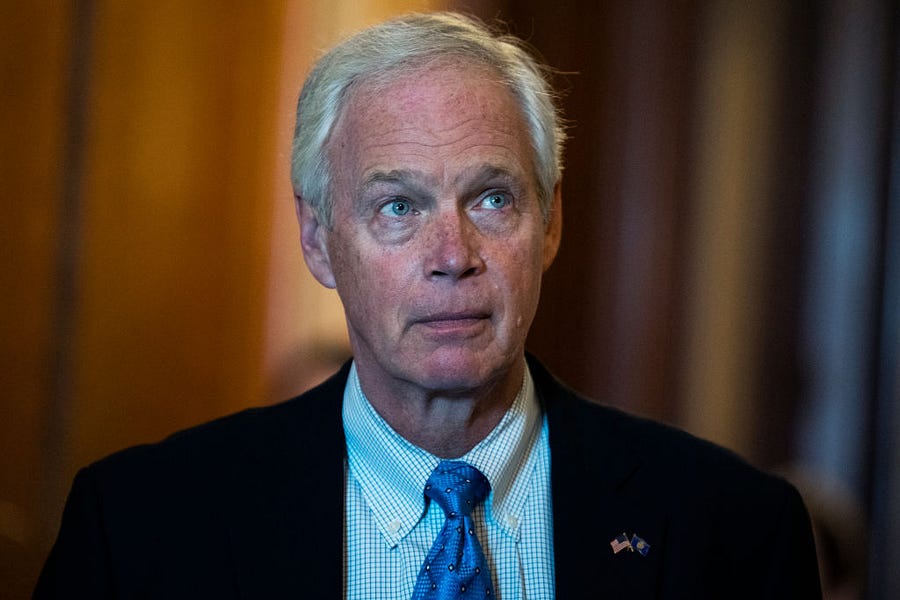

GOP Senator Ron Johnson dropped by the last week of July to do just this. On Tuesday, voters will weigh in on a consequential Senate contest and gubernatorial election. Down ballot, there is also the state assembly, attorney general, and secretary of state races.

Johnson, who is running unopposed, quickly attracted a crowd around the fair’s GOP booth. After posing for pictures, his campaign staff sent constituents away sporting green and white Ron Johnson stickers. Moments later, during his circuit around the rest of the booths, a couple came up for a picture, then lingered to voice some of their concerns.

“They ordered votes,” the man said, shaking his head. He went on to reference a recent controversy in Racine County over how voters request absentee ballots. Then he thanked Johnson for how the senator has represented Wisconsinites.

Racine County Sheriff Christopher Schmaling alleged that the state’s voter information and registration website, MyVote Wisconsin, is vulnerable to fraud. For proof he pointed to actions by right-wing activists who “tested” the system by requesting ballots on behalf of others and for different addresses, with the activists claiming the ballots had been sent to addresses that did not correspond with the voter’s information.

Wisconsin Elections Commission Administrator Meagan Wolfe responded by saying that individuals who attempted to obtain absentee ballots for others committed a crime and “does not demonstrate a flaw with MyVote.” The WEC has said that the website does not automatically send out ballots.

Talking to other fairgoers made clear that, though there are only two months to go until the 2022 midterms, the idea that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent—and that election administration in Wisconsin and the United States in general is untrustworthy—has become deeply rooted in certain parts of the Republican Party.

“Voter integrity. That’s number one on my list,” David Quicker, one Republican at the fair told The Dispatch.

“I’m still questioning whether we’ll have a fair election. You know we’ve got George Soros funding all of this crap,” he added, a reference to the billionaire who has donated millions to the Democratic Party and liberal super PACs and become a favorite punching bag of the conspiracy theorist right. Quicker also brought up concerns of ballot box stuffing in dropboxes.

Others echoed similar sentiments.

“I hope it turns out to be honest,” one 74-year-old Republican who identified herself only by her first name, Joyce, told The Dispatch about the election. She voiced a variety of concerns about the election, recalling a story about Pennsylvania election workers blocking windows while counting votes during the 2020 election and claiming that she received two ballots for her husband, who she said passed away in 2019.

Washington County is one of the redder bastions in the Badger State. One booth at the fair, featuring a “Break-a-Bottle Beer Bust” game, was liberally draped with Donald Trump regalia, including a Women for Trump sign, Let’s Go Brandon T-shirt, and, at the center of the booth, a flag printed with “Trump 2024: The Revenge Tour.”

Booth operator James Carlyle, an Oostburg resident who also runs a business selling Trump gear and sported a Let’s Go Brandon hat himself, told The Dispatch that sales have only increased since the election.

For voters who entertain these beliefs, Johnson’s willingness to lend credence to their concerns has earned him fervent loyalty.

Though there are deep red and deep blue pockets in the Badger State, politics in Wisconsin are notoriously difficult to pin down. The state currently has a Democratic governor in Tony Evers, and senators from opposite parties: Johnson was first elected in the Tea Party wave of 2010 but fully embraced Donald Trump’s MAGA-style politics, while Democrat Tammy Baldwin is the state’s first female senator, as well as the nation’s first openly gay senator.

Trump is unpopular in the state according to state polls: Marquette Law University found in June that only 34 percent of respondents had a favorable view of the former president. But the same survey found President Joe Biden’s approval rating had sunk to a new low—just 36 percent as of June.

In 2016 Trump was the first Republican since Ronald Reagan to carry the state,, but he lost the state to Joe Biden by 20,000 votes out of more than 3 million cast in 2020.

The state’s largest GOP-leaning counties, the suburban Milwaukee “WOW” counties of Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington, soured slightly on Trump in 2020, and his margin of victory shrunk compared to 2016.

However, the Republican Party fared better down the ballot, aided by maps drawn in 2011 by GOP legislators: Republicans expanded the number of seats they controlled in the state Senate and shed only two seats in the State Assembly. Despite being outspent by Democrats, the GOP ultimately kept their majorities in the statehouse.

It’s unclear whether election concerns have the same resonance in more suburban areas.

Democrats see Wisconsin as one of their best opportunities to pick up a Senate seat and hold onto control of the upper chamber—they’ve pinpointed Johnson as the most vulnerable GOP incumbent on the ballot this year. And Democrats have sought to brand Johnson as the senator of conspiracy theories.

Bolstering this approach has been a rash of bad headlines, largely driven by the senator’s own comments on controversial issues: He’s landed in hot water for inflammatory statements about January 6 and who participated in the insurrection, expressed skepticism of the COVID vaccines and toyed with other COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and at times boosted allegations of voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s editorial board called for Johnson to resign for his involvement in events leading up to January 6 (Johnson initially said he would vote to reject Biden electors from some states, but after the Capitol riot ultimately chose not to do so). The senator chose to respond to the paper’s readers directly, writing an editorial where he argued that a “debate” around alleged voter fraud was necessary.

And in June, the January 6 committee aired evidence that Johnson’s chief of staff tried to send lists of fake presidential electors to Vice President Mike Pence on January 6.

In Wisconsin, a group of 10 Republicans went to the Wisconsin State Capitol in December 2020 and signed documents claiming that they were presidential electors for Trump—they said they wanted the paperwork in case Biden’s win could be overturned.

Johnson said that he got a request from Dane County, Wisconsin, attorney Jim Troupis to pass information about this group of would-be electors to Pence. Johnson said he connected the attorney to his chief of staff Sean Riley via text. Riley then made the offer to Pence, but a Pence aid shut down the effort. Initially, Johnson spokesperson Alexa Henning called the effort a “staff to staff exchange.”

Johnson denied any wrongdoing, telling The Dispatch that “my total involvement was a few seconds.” He said that his voters aren’t concerned about how his office handled the situation.

Such controversies seem unlikely to materially injure Johnson with the most conservative Republicans. It’s not clear whether voters closer to the center will dismiss them as easily.

The latest round of state polling in June, from Marquette Law School, did not look too rosy for Johnson.

Johnson trailed his Democratic opponent Mandela Barnes by 2 percentage points—within the polls margin for error. But Johnson is downright unpopular among a plurality of voters: Around 37 percent of respondents viewed Johnson favorably, while 46 percent viewed him unfavorably. This is a slight uptick from April, where 36 percent of respondents had a favorable opinion of the senator.

Charles Franklin, pollster and director of the Marquette Poll, told The Dispatch in June that compared to 2016, Johnson has less of a window to impress voters unfamiliar with him. During his last reelection, around 35 percent of voters counted themselves as unfamiliar with Johnson: “But the ‘don’t know’s’ went down, and the favorables went up with almost no change in unfavorables. He converted ‘don’t know’s’ into favorables in that recovery period.” This June, 16 percent of voters said they hadn’t heard enough about him. “There’s a much smaller pool of people he could convert into favorables,” Franklin said. “The trend from 2019 has been almost entirely a growth in unfavorables.”

But as Johnson’s defenders are quick to note—prognosticators who have predicted Ron Johnson’s political death have been wrong in the past—he toppled Democratic incumbent Ross Feingold in 2010 and beat him in a 2016 rematch—and the sophomore senator is betting he will once again come out on top of bad news in the poll and negative news reports.

“Well, I haven’t put a whole lot of faith and hope in polls. Not in 2010, not in 2016. Had I paid attention to ’em I probably would have dropped out of the race.” Johnson said in an interview with The Dispatch, “All that being said—Wisconsin is always gonna be a close race. We’re generally vying for a pretty small sliver in the middle.”

And as one GOP operative close to the campaign pointed out—poor polling doesn’t mean that independent voters or more moderate Republicans will cast their votes for Johnson’s Democratic opponent.

On the other side of the aisle, Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes has racked up high-profile endorsements from Democratic Sens. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, prominent Democrats in the House from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, as well as the Working Families Party.

Barnes, 35, was the first black lieutenant governor of Wisconsin after Tony Evers’ election that ousted then-Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican. Barnes would be the state’s first black senator if elected.

“Ron Johnson has got to go. I’m going to try and elect Mandela Barnes,” 73-year-old Clarence Thomas, a Wisconsin native and Democrat voter, told The Dispatch. He said he supported Barnes’ support for abortion rights, position on climate change, and other policies. Thomas, who is black, also added wryly: “Plus he looks more like me than Ron Johnson.”

Barnes initially faced competition from NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks executive Alex Lasry, as well as state treasurer Sarah Godlewski and Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson. But all three dropped out the last week of July and endorsed Barnes.

Part of Johnson—and Republicans—strategy against Barnes will be to argue he is too far to the left for Wisconsinites to swallow. He’s campaigned with Rep. Ilhan Omar, a progressive House Democrat—though he’s sought to downplay such support since.

University of Virginia’s Sabato’s Crystal Ball on Thursday rated the state Senate race as “leans Republican.”

Johnson is likely to benefit from the dissatisfaction voters feel with the political status quo. And with Democrats in control of the White House and Congress, Republicans have an easy punching bag.

“When you look at polling that shows 75 to 80 percent plus the American population thinks we’re on the wrong track,” Johnson pointed out. (A Monmouth University poll found Tuesday that 88 percent of Americans believe the country is headed in the wrong direction—an all-time low going back to 2013.)

He said that voters are still most concerned about kitchen table issues: “They’re concerned about 9.1 percent inflation—record gasoline prices. $4 for a gallon of gas is still not a deal. So that’s what’s primarily on people’s minds—how can they get by?”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.