One of the most ignorant and dishonest of the Democratic talking points that show up during budget debates like the one we currently are having is: “We could fix our budget problems if only we would return to the tax policies we had in the 1950s and 1960s, a time of widely shared prosperity with top tax rates above 90 percent for the rich.”

In the 1950s, there were very high statutory tax rates, meaning that a taxpayer could, in theory, pay a top marginal rate of 92 percent. But this applied to very few taxpayers and to a very small share of their income. That is why when you look at the data from a more meaningful economic perspective, U.S. taxes were a lot lower in the 1950s than they are today: Federal tax revenue from 1950-60 averaged only 16.8 percent of GDP, as opposed to the 19.6 percent of GDP collected in federal taxes in 2022. (GDP terms are useful because they capture the fact that our population is both larger and richer.)

Which is to say, if we had 1950s taxes (16.8 percent of GDP) and 2022 spending (25.1 percent of GDP), then our deficit would be a lot worse—not 5.5 percent of GDP but 8.3 percent of GDP; conversely, if we had 1950s spending (17.2 percent of GDP) and 2022 taxes (19.6 percent of GDP), we would be running a large surplus.

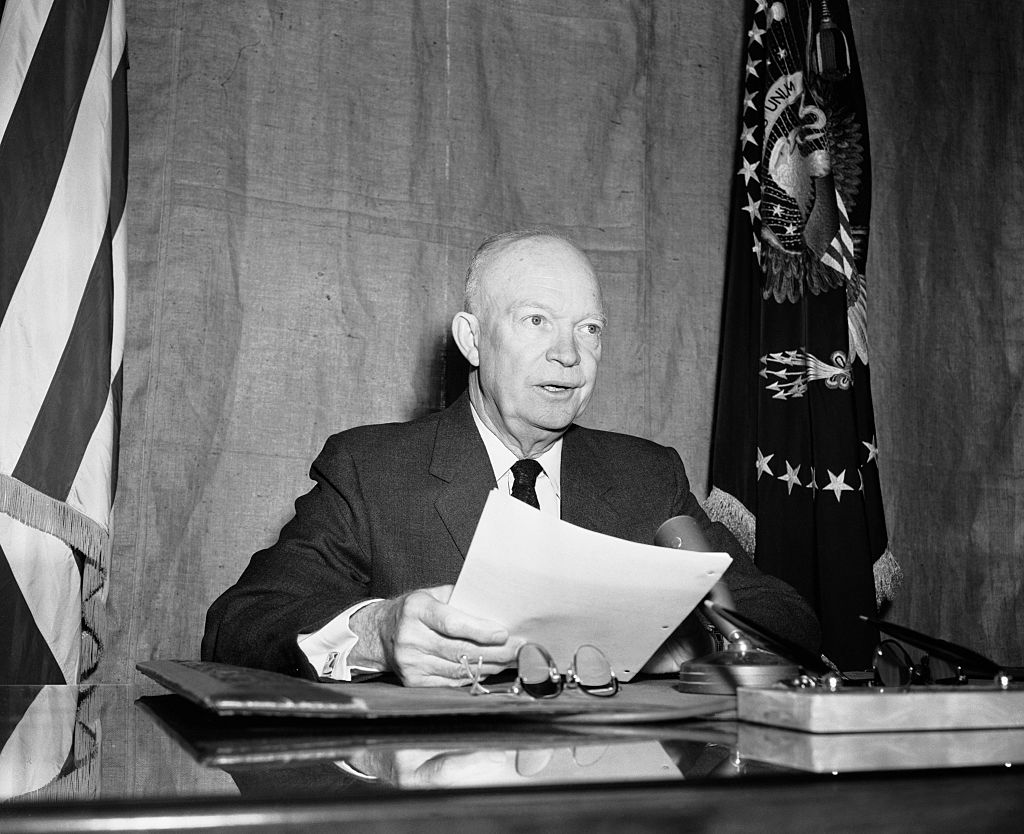

There is much to admire about Eisenhower-era government in the U.S., but the idea that Eisenhower-era tax policies would enable Biden-era spending is not supported by the actual economic data.

(Some of the people who deploy that talking point are not familiar with the facts—but, unhappily, some of them surely are. You can rule an unfree society with lies, but you cannot govern a free society with lies.)

Some 1990s nostalgists make a similar argument for Clinton-era tax rates. (The fiscal policies of the 1990s are better described as Gingrich-era—it is Congress, not the president, that writes tax laws and makes spending appropriations, but I won’t dwell on that in this column.) You’ve heard it before: “Remember the 1990s? Hurray, Democrats! We had a budget surplus back then with higher taxes!”

No, we didn’t.

Federal deficits averaged 2.1 percent of GDP in the 1990s; if you want to take the Clinton years (1993-2001) exclusively, then you end up with a modest deficit of 0.5 percent of GDP, only slightly larger than the average deficit of the 1950s (0.3 percent of GDP). But, again, the critical difference driving the deficit is not in tax revenue (18 percent of GDP in the 1990s vs. 19.6 percent in 2022 or the 19.2 percent estimated average for the next five years) but in spending: Spending from 1990-2000 averaged 19.8 percent of GDP, meaning that a return to 1990s spending levels would nearly erase the deficit, whereas a return to 1990s tax levels would make the deficit worse.

If you really want to get into the weeds, the fictionalized progressive account of federal spending looks even sillier. In the 1950s, defense accounted for an average of 58.3 percent of federal spending, as opposed to only 12.2 percent of outlays in 2022—which is to say, we were spending almost five times as much on defense (as a share of the budget) than we are today. In economic terms, we were spending 10 percent of GDP on defense in the 1950s, more than three times as much as we are spending today. The growth has been on the social-spending side: “Human resources,” meaning welfare and social spending writ large (including entitlements and means-tested programs, education support, etc.) is now 75 percent of the federal budget, as opposed to 23 percent in the 1950s. In the 1950s, payments to individuals (direct payments and grants to states for such payments) ran 3.8 percent of GDP; in 2022, it was 18.1 percent of GDP, almost five times as much. Which is to say, in GDP terms we’ve cut defense spending by 70 percent since the 1950s and increased welfare spending 476 percent.

Overall, we have gone from a defense/non-defense spending split of about 70/30 in 1954 to spending only about 12 cents of every federal dollar on defense in 2022, with the rest going to non-defense spending dominated by entitlements and welfare programs of various kinds.

In terms of budget priorities, defense and social spending have basically changed places since the Eisenhower years—something to keep in mind when you hear progressives talk about going back to that postwar golden age of federal fiscal policy. I don’t know that we need to spend 10 percent of GDP on the military in 2023, but I am even more skeptical that we need to be spending 20 percent of GDP on robbing-Peter-to-pay-Paul programs. Social Security payments were less than $1 billion in 1950, and they are well over $1 trillion today. A trillion, for you English majors out there, is a thousand billions. If you want to know where the money goes, there goes the money.

In the same way that our Democrat friends want voters to believe we can have Scandinavian levels of welfare spending without Scandinavian levels of taxation (including relatively heavy taxes on the middle classes), we cannot go back to 1950s or 1990s levels of taxation and solve our deficit problems—not without a return to commensurate levels of spending.

As always, please do look at the data for yourself. Some of it may surprise you.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.