In 1944, Democrats nominated and Americans elected a president who was very nearly dead.

It was the weakest electoral showing of Franklin Roosevelt’s four runs—just 53 percent of the popular vote. That was about the same as Barack Obama in 2008, which is high by our current conception but not on par with FDR’s priors, particularly his 61 percent in 1936.

Thanks to Democrats’ lock on the South and the largest cities, which were all in the North back then, a more-modest popular vote victory was good enough to win 81 percent in the Electoral College, better than any modern president besides Ronald Reagan’s double landslides.

Republican Thomas Dewey managed to win 12 states, 10 more than the Kansas sunflower Alf Landon did in 1936, but Roosevelt’s victory was never in serious doubt, even if Roosevelt’s ability to serve out the term he won was.

Ten days before the president accepted the Democratic nomination in July 1944, the president’s medical team diagnosed him with acute high blood pressure and congestive heart failure and said he would likely not survive another term in office. But doctors were saying what those around the president, and probably Roosevelt, already knew. He looked terrible—seeming 20 years older than his 63 years—and was wasting away. The diagnosis was kept from the public, but it was obvious to the party bosses who came in contact with the president.

That’s what led to the scramble, wonderfully recounted in Benn Steil’s book The World That Wasn’t: Henry Wallace and the Fate of the American Century, to dump Wallace, the sitting vice president. The public-facing argument for making the switch for Missouri Sen. Harry Truman was about politics, with race watchers saying that the ultra-progressive Wallace could cost Democrats in the Deep South. There were reports, too, about bad blood between Wallace and the other members of the administration.

But the real reason the bosses—and Roosevelt—knew the switch was necessary was that Wallace, a Stalin admirer who had been thoroughly duped by the Soviets on a trip through Siberia, could not be allowed to assume the presidency upon FDR’s inevitable demise. The new world order for after the war that Roosevelt was working himself to death to try to establish would be wiped out by a Wallace presidency that let the Soviets have their way with Europe.

Roosevelt was inaugurated for his fourth term on January 20, 1945. On March 1, he revealed some of the extent of his illness when he addressed Congress on plans for the end of the war seated in a wheelchair, the heavy braces that allowed him to stand on his polio-ravaged legs having become too much for him to bear. On April 12, sitting for a portrait at his home in Warm Springs, Georgia, he died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage.

Truman ascended to the presidency, led the effort to finish off the Japanese Empire, and, as Roosevelt had hoped, held the line against the Soviets.

So what about Joe Biden, who was, remarkably, alive when all this happened? At nearly 3 years old when Roosevelt died, it’s possible that Biden might even have some memory of the moment, or at least say that he did. Of the five living former presidents, only Jimmy Carter, now nearly 100 and out of office for 43 years, was alive when Truman took the oath of office.

Biden has talked about being a “bridge” to the next generation of Democratic leaders. That implicit promise to seek just one term was, as it turned out, just some stuff politicians say. What Biden has really aimed to be was a bridge to the past, a way to take America back to the way it was before. Before Donald Trump, yes. But also before the 21st century. The prime of Joseph R. Biden Jr. was 30 years ago when, at the time of the fall of the Soviet Union, America was still living in the world that Roosevelt and his designated survivor had helped to fashion. An appealing, if impossible dream.

Biden and his admirers may see a lot of FDR in him. They may even imagine his situation in 2024 to be like the ailing Roosevelt’s last campaign 80 years ago. It is a dangerous way of thinking. Aside from the many differences between the two men, the state of the world, the media, and the nature of politics, there is this: Roosevelt may have been almost sure to die in his next term, but he was also almost sure to win it.

The problem Democratic bosses faced in 1944 was in managing success. The one they confront now is in avoiding a generational catastrophe.

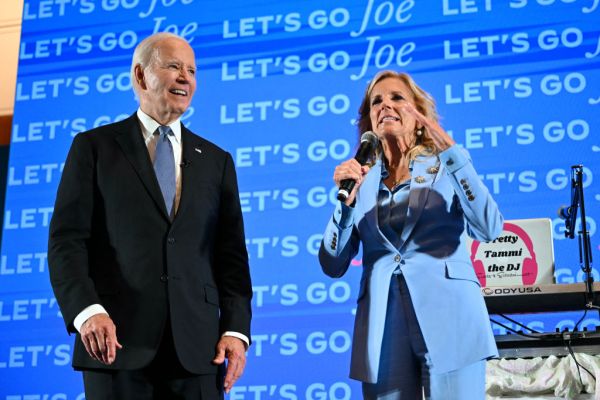

We could debate how much Biden’s appalling appearance and performance at last week’s debate will hurt his standing with voters, but even the most optimistic Democrats would allow that significant harm was done. We won’t know how much until we see some good polling on the state of the race, which, because of Independence Day, will be delayed by a week or so. But even in the early emanations, we see bad news indeed.

Biden trailing in New Hampshire? Woof.

At the heart of Biden’s FDR problem is that when the world concluded that he was obviously not fit for another four years, the incumbent was already losing.

In an average of high-quality national polls going into the debate, Biden was down by 2 points nationally. Bear in mind that for Democrats to overcome the advantages Republicans enjoy in the Electoral College because of the allegiances of rural and small-town voters, the blue team needs to win the national popular vote by something more than 3 points. Biden won by 4.5 points and still found himself in a squeaker with the incumbent in 2020. Hillary Clinton won the national popular vote by more than 2 points and ended up with just 42 percent of the electoral votes in 2016.

Trump wins a tie with Biden. Indeed, the idea of forcing the earliest general election debate in presidential history was to help Biden catch up to Trump. What started as a vehicle to reset the race and allow the incumbent to start trying to build a lead will end with Biden almost certainly being at his worst deficit of the campaign so far.

Let’s imagine, though, that the race was basically unchanged by the debate. We know that’s not true, but play along. If Biden were to lose the national popular vote by just 2 points, he’d hand Trump a smashing Electoral College victory—more than 300 electoral votes, the largest for a Republican since 1988.

Already poised to lose the Senate before the debate, Democrats could almost certainly expect to see Republicans take a 52- or 53-seat majority. In this imagined world where the debate didn’t hurt Biden but merely deprived him of a chance to reset the race, the downdraft from the top of the ballot would also probably kill Democrats’ hopes of retaking the House.

So now ask yourself how much the debate will really have hurt Biden. Maybe you think it doesn’t matter all that much and he will dip only a couple of points. We’re a long way from Election Day and, certainly, if Democrats do decide to stay course, some of the damage done last week could be repaired.

That makes the best-case scenario for Biden look like spending the 10 weeks until the next debate making up lost ground and then trying to claw his way to a tie (which, as we know, is really a loss) to try to deliver the performance he was supposed to give the first time around.

Whatever the perils of an open convention or the elevation of Kamala Harris to the top of the ticket, it has to be a lot more appealing to Democrats than the increasing prospect of Trump back in power with both houses of Congress on his side and a federal judiciary dominated by conservatives.

Democrats in 1944 were thinking about shaping a future of their dreams. This time, they’re thinking about preventing one of their nightmares.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.