When a natural disaster strikes, the response is never fast enough for the people involved who are suffering. In the aftermath of a widespread catastrophe like Hurricane Helene, the work of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) on the ground may not be visibly front and center. That’s because FEMA is a disaster coordination agency, working with a large and complex network of disaster relief organizations.

FEMA employs over 20,000 people in Washington, D.C., and across its 10 regional agencies. During a disaster it also utilizes thousands of contractors, who can assist with logistics, debris removal, temporary housing, and specialized services.

At a time when FEMA is juggling responses to two hurricanes, the agency has found itself having to knock down rumors circulating on social media about its response to Helene, how it spends funds, and how it distributes aid. In some ways, it’s nothing new: Criticism has surrounded FEMA relief efforts for more than 30 years. Going back to hurricane Andrew in 1992, there were calls for the “disbanding of FEMA” after its slow federal response. With the evolution of social media and the rapid dissemination of unverified information, the agency has become more proactive in its messaging than ever before, posting 12 messages on its website in the last week seeking to debunk misinformation.

The evolution of federal disaster relief.

Congressional funding for disasters goes back to 1803, when money was appropriated to support local recovery from a devastating fire in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Over time, the web of disconnected agencies involved in coordination and dissemination of resources in times of disaster became too tangled and the need for coordinated federal relief for disaster victims became clear. Simultaneously, there was mounting pressure to create a more organized system for state and local emergency managers (formerly called civil defense directors) who needed a “one-stop shop” when disasters occurred. President Jimmy Carter’s executive order on April 1, 1979, established FEMA. The agency opened its doors just days after the Three-Mile Island nuclear accident.

Just as FEMA was born out of crisis, it continues to evolve and be redefined by major disasters. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, swept FEMA and 21 other agencies under the newly created Department of Homeland Security, taking away FEMA’s Cabinet position. This extra level of bureaucracy between FEMA and the president proved to be unwise during Hurricane Katrina, contributing to the slowed response by the federal government. After a post-Katrina review, Congress passed legislation that significantly reorganized FEMA, affirming it as an independent agency reporting directly to the DHS secretary. The FEMA administrator was elevated to an adviser to the president on all emergency management-related national matters, and the agency gained greater authority and a clearer role in emergency management. The act also emphasized preparedness for all types of disasters, including terrorism.

In its current structure, FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell reports to Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. FEMA is organized into 10 regions across the United States. FEMA Region IV is the predominant region dealing with Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton, encompassing the Carolinas and Florida and much of the Southeast. A regional approach allows FEMA administrators and their staff to develop relationships with groups of states that face similar hazards and ensure that partnerships are developed prior to disasters occurring. Each FEMA region maintains a Regional Response Coordination Center (RRCC), which provides the initial response coordination across various levels of government for a specific incident. Once the disaster has been federally declared, a federal coordinating officer from FEMA establishes a Joint Field Office (JFO) in the disaster zone of each state to coordinate with a State Coordinating Officer to manage federal and state response.

When does FEMA get involved in disaster assistance?

It is important to understand that disasters are local events. Each locality—be it a town, borough, city, parish, county, or other political jurisdiction—provides the initial response to a disaster.

When the scope of the disaster reaches a threshold where more resources are needed than a locality can provide, local officials declare formal emergencies or disasters and request aid from other local jurisdictions and/or the state. If state officials determine that additional assistance is needed, they will declare a disaster and request federal aid. Once the president declares a disaster, federal assets are deployed through a mobilization process guided by FEMA. State governors, through their emergency management agencies, request specific resources and integrate federal resources into state and local operations. This initially occurs through FEMA’s regional centers until the establishment of a field office, where state and federal emergency management personnel work side-by-side to coordinate resources. States may also assist each other with personnel such as the National Guard, equipment, and other resources under the Emergency Assistance Compact created in 1996.

Federal resources coordinated through FEMA are designed to support the state and the local community in the management of a disaster. FEMA is not a “take charge” agency, and local government officials remain in control of their own community by requesting assistance up the chain to state, regional, and federal levels.

Does FEMA do all the relief work on the ground?

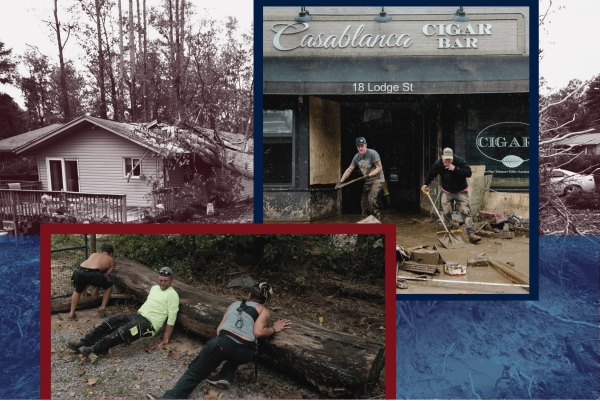

Not necessarily. Assistance from FEMA may not come from people with “FEMA” on their shirts; it may look like aid mobilized from across the country in military, public agency, and private partnerships. These efforts are the result of FEMA coordinating and pushing resources to the state and local level. For this reason, local first responders and state emergency management agencies may require that disaster volunteers work through an organization to help disaster victims.

Much of the help comes from nongovernmental organizations, including faith-based, community-based, and other nonprofit organizations that provide human services to disaster survivors. These organized groups—such as the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, and Mennonite Disaster Service—have a mission in the network of assistance, follow safety and legal guidelines to operate in disaster areas, have background-checked employees to avoid scammers, and do the job of mass feeding, running shelters, managing donations, repairing housing, and more.

Are donations of food and clothing helpful after a disaster?

After a disaster occurs, donations of all types typically flood in, but the space they take up is considerable in a disaster area where safe space is limited. All donations of goods must be warehoused, coded, inventoried, and put into a computer system so that when local responders request 12 pallets of water the inventory is tracked. When donations do not go to a designated distribution center, semi-trucks can clog highways as they wait to be unloaded, keeping requested resources from flowing into the scene and creating bigger issues for the response process. This was one of the lessons learned from the response to Hurricane Andrew, which hit Florida in 1992.

How is FEMA funded and how are its funds spent?

FEMA is funded through congressional budgetary appropriation each year; more funding comes from additional supplemental appropriations. Congress provides these supplemental appropriations in response to large disasters like Hurricanes Helene and Milton, and President Joe Biden has asked it to provide additional funding to FEMA to avoid a shortfall by the end of the year. In 2005, when Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma all hit over a span of fewer than 90 days, Congress appropriated an additional $68 billion in supplemental funding.

FEMA helps both governments and individuals/households through the Disaster Relief Fund, a single spending account under FEMA. The money is used for many actions related to disaster mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery: repair, replacement, and improvement of damaged infrastructure; clearing debris; providing critical services; covering the costs of home repairs, property replacement, and other household needs; and implementing projects to mitigate future disasters and repetitive damages. For example, FEMA provides disaster survivors who apply an upfront $750 payment to cover essentials while the agency reviews whether an applicant qualifies for additional assistance. On a larger scale, FEMA assistance goes into short- and long-term recovery projects until the area is deemed back to normal in terms of population and economic recovery.

The 1988 Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act provides the legal authority for most FEMA programs and federal disaster response and is the legal mechanism through which resource requests are made by state and local governments.

The Stafford Act spells out the categories of assistance offered to individuals and households under federally declared emergency or disaster declarations. While residents’ own insurance is the primary expected cost recovery method for property damages, needs like housing assistance, home repairs, food, relocation assistance, legal services, case management, crisis counseling, transportation services, loans, and unemployment assistance are all covered under provisions of the Stafford Act.

In addition to FEMA support, insurance should also kick back into the communities once adjusters come through and conduct damage assessments on impacted properties.

The potential for an independent FEMA.

As disasters become more frequent, costly, and complicated, various groups and agency advocates feel strongly that the FEMA administrator should be reinstated to a Cabinet-level position and the agency removed from the Department of Homeland Security. To that end, in 2023 a bipartisan bill was introduced by Louisiana Rep. Garret Graves and Florida Rep. Jared Moskowitz (former head of the Florida Division of Emergency Management) that would make FEMA an independent Cabinet-level agency once again. While FEMA in the past could divert resources for different disaster “seasons” like wildfires and hurricanes, natural disasters happen more concurrently now, straining the response when multiple major disasters are declared at one time.

“There is no doubt that in the future FEMA will be busier than ever before and this move will help cut unnecessary red tape and make FEMA quicker,” Moskowitz said.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.