New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo was addressing reporters on March 15, back before the country was overrun with amateur epidemiologists.

“You are not going to stop people from being infected. There are all sorts of percentages about what percent of the population will be affected. 40 percent, 50 percent, 60 percent,” he spitballed. “You will not be able to control that. Nobody thinks you can. But, you can make efforts to slow the spread, because the real question here is can your health care system manage the influx of patients. That’s all this is about.”

Later that same day, Cuomo cited the phenomenon—also known as “flattening the curve”—in his decision to close all schools in New York City, Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk counties.

“Any pandemic like this runs the risk of exceeding our health care system capacity,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar argued in that day’s coronavirus task force press briefing. “That is precisely why the president and vice president’s strategy is, as Dr. [Anthony] Fauci has repeatedly spoke: to delay and flatten the curve. The point of this is, instead of a spike of the curve, to delay and flatten that curve with the hope that you can keep the utilization of resources to be within the health care system’s capacities.”

President Trump would announce his “15 Days to Slow the Spread” guidelines the following evening.

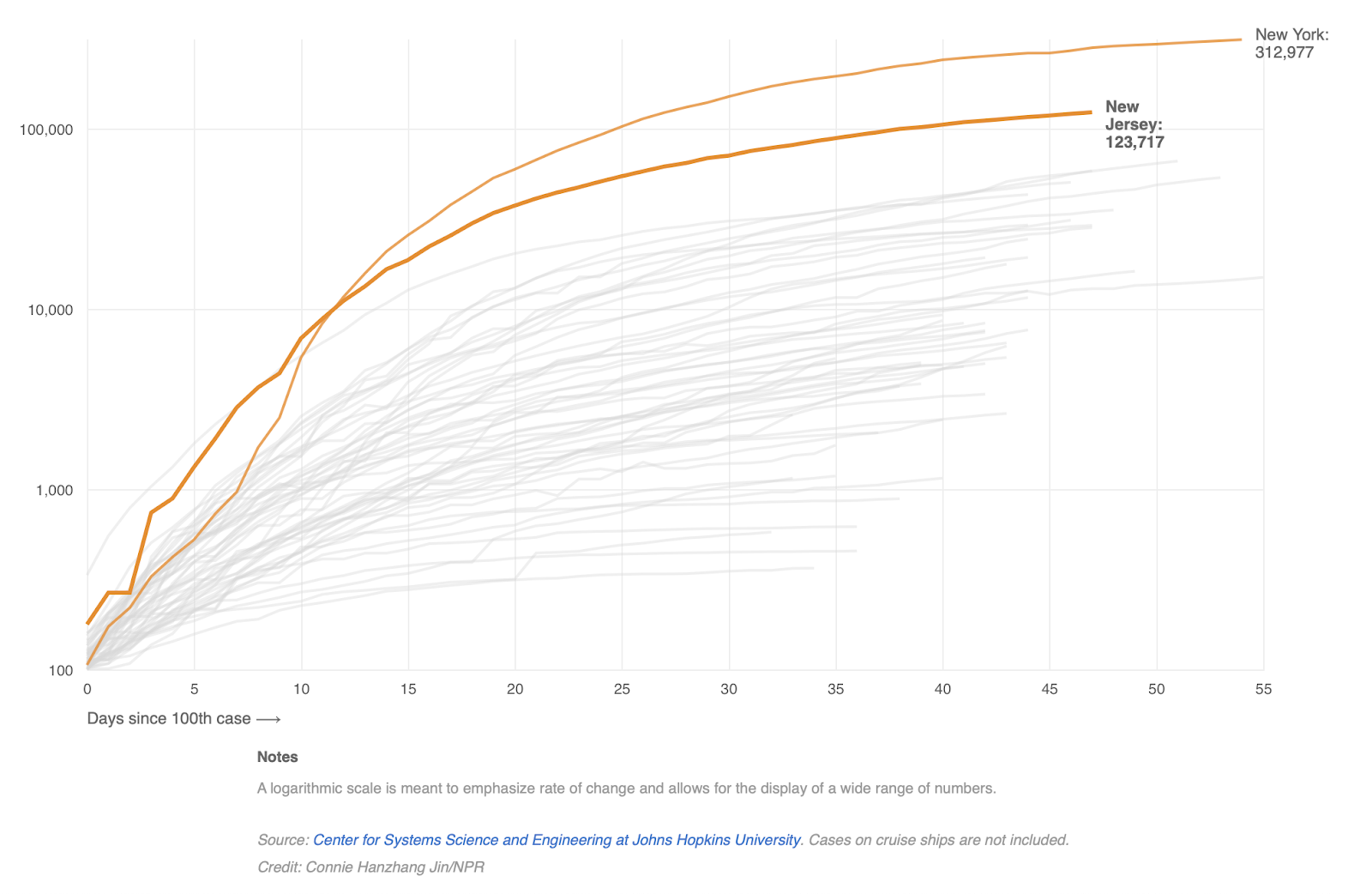

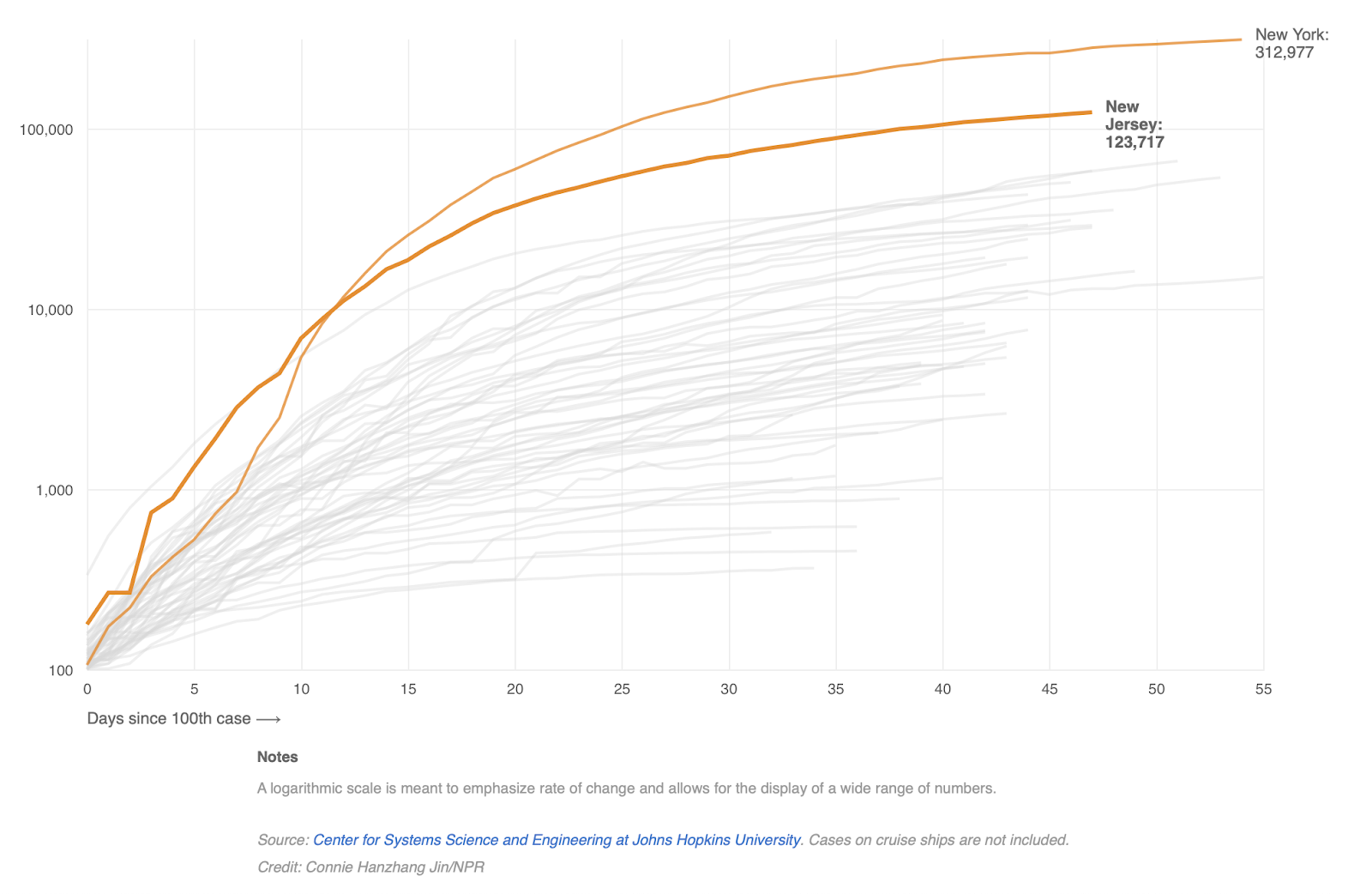

Fifty days later, more than 1 million Americans have been infected, 30 million are unemployed, and nearly 70,000 people have died. But most states’ curves (though not all) have been flattened.

Hospitals in New York City, Detroit, and New Orleans came close to being overrun—makeshift facilities were heroically constructed, essentially overnight, to handle anticipated surges—but few, if any, of the most dire early projections of inundation and rationing came to pass. New York has sent hundreds of surplus ventilators to states with more acute need. As Andrew Egger reported for The Dispatch last week, many hospitals, clinics, and private practices around the country are empty, on the brink of insolvency as bans on non-essential procedures have left their waiting rooms barren. If, as Gov. Cuomo said, a majority of Americans are likely to contract the virus, and forestalling overwhelmed hospitals is truly “all this is about,” mission accomplished, right?

Not exactly.

When it became clear in early March the coronavirus was running rampant in the United States through community transmission, public health and political leaders raced to stave off the gravest and most immediate threat: an immediate deluge of severe infections rendering existing health care infrastructure underwater. Thus, the deafening chorus of “flatten the curve.”

But that chorus was so loud, it may have drowned out what comes next.

“We do want to flatten the curve,” President Trump said when asked by a reporter on March 27 how long Americans should expect to be locked down. “We want to see that curve start heading down in the other direction, at a minimum. … I certainly want to get it open as soon as possible. I don’t want it to be long, but we also want it to open safe. Otherwise, what did we do?”

Flattening the curve—while certainly an accomplishment—is not an end in and of itself, but rather a means of buying time. Time to source and manufacture ventilators and tests, time to build up testing and contact tracing infrastructure, time to formulate reopening strategies, and ultimately, time to develop effective therapeutics and an effective vaccine.

The Trump administration’s Opening Up America Again guidelines recommend states not enter Phase One of reopening armed with a flattened curve alone. Rather, governors should, according to the White House, keep lockdown measures in place until their state sees “downward trajectory of documented cases within a 14-day period” and has built up enough hospital capacity to “treat all patients without crisis care.”

Very few states have met these criteria. As former Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has noted in recent days, our national curve is not declining, but rather leveling off. “We face a persistent plateau of 30,000 [new] daily cases and 2,000 [daily] deaths,” he tweeted. The numbers are staggering, but the shape of the curve was expected. As Gov. Cuomo and Secretary Azar noted, the inherent tradeoff in decisions to spread out infections is, of course, time.

Take Maryland, for example. “Had we spiked and had all this stuff right away, it would have been overloading the system, but it also would have happened faster,” Governor Larry Hogan said in a press conference last month. “The fact that we’ve dampened down and flattened this curve means it’s a longer period of time and we have this longer plateau. So while we’re going to not have this overload of the system, it also means it’s going to take a while for us to be able to get back … People are going to have to get ready for that.”

Poll after poll after poll after poll suggests most people are. But the extended lockdowns are placing real strain—financial, emotional, marital—on countless families across the country. And a vocal minority are beginning to ask: Have public health officials strayed from their original rationale for the social distancing requirements? Has the country’s collective goal shifted from spreading an inevitable number of infections out over time toward reducing that inevitable number?

The objective “really is to maintain that flattened curve,” said Dr. Crystal Watson, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins’ Center for Health Security, in an appearance on the FiveThirtyEight Politics Podcast. “We don’t think that we can eliminate this virus from our country altogether, at least not until we have a safe and effective and widespread vaccine, and even then it may be difficult.”

“We came very close in New York to having hospitals that were pretty overwhelmed,” she added. “I don’t think we’re out of the woods, by any means. If we were to lift all measures right now, we would see a big resurgence of this virus in our communities and we would have hospitals that were overwhelmed.”

And they very well still could be. “I am not dismayed by the fact that there are empty beds,” Dr. Barry Bloom of the Harvard University Chan School of Public Health told The Dispatch. “In fact, I’m encouraged by that. Because if there are outbreaks and spikes and even a second wave, we can’t start all over again, preparing hospitals to be overwhelmed. So it’s a good investment to have the time to prepare the hospital systems, the PPEs, the diagnostic procedures, and all of that, so we could respond a great deal more quickly.”

Dr. Chris Beyrer—an infectious disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health and president of the International AIDS Society from 2014 to 2016—argued that spiking the football now and overreacting to this initial flattening would be a mistake. “It seems like a short-term win,” he told The Dispatch last week. “But it could lead to prolonged community transmission and more economic and social pain.”

A popular simulation in the Washington Post a few weeks back depicted the various paths an infectious disease could weave throughout a society. If left unchecked, the number of people with the virus (burnt orange below) would grow exponentially until a critical mass had been infected, at which point recoveries (purple) would multiply. By implementing effective social distancing, however, this hypothetical civilization could not only “flatten the curve,” but limit the number of healthy people (turquoise) infected in the first place.

In the real world, the more public health officials are learning about COVID-19, the more important this latter priority has become. According to Dr. Beyrer, officials are operating with the understanding that COVID-19’s actual case-fatality rate falls somewhere between 1 and 4 percent; the United States’ current observed mortality rate is 5.9 percent.

“People are presenting with what looks like a heart attack, they may or may not have other COVID-related symptoms, and those are turning out to be COVID,” Dr. Beyrer said, referencing a 51-year-old friend of his whose autopsy last week turned up a COVID-19 infection after he ostensibly died of a heart attack. “There are people presenting with acute onset of confusion who have mental status changes. And it turns out that this virus can infect the brain and give you encephalitis, and that’s COVID, which we hadn’t appreciated. The same with the renal damage. The kidney damage, which is turning out to be more of a problem.”

“We’re also starting to understand that if you survive the acute period, that people are continuing to have serious health challenges in recovery, including with heart, with kidney, with lung function,” he added. “More people are having more lasting health impacts. So all of that is suggesting that it’s a serious infection and it leads to a serious disease. Not for everybody, obviously, but for the people who do go on to progress. And it’s basically about 1 in 5 people who get this will have a more serious course.”

“The data are pretty striking that people over the age of 60 have much higher mortality when they’re coronavirus infected than younger people,” Dr. Bloom noted. “But in a sense … everybody is vulnerable. There are kids that are dying in infancy from this virus in China and in the U.S.. And we have no idea.”

With all of these unknowns, Dr. Beyrer argued the United States should not throw its hands up and accept the virus running its natural course. “I think infection control still matters enormously,” he said. “We do want to reduce as many infections as we can.”

Photograph by John Cordes/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.