It’s hard to imagine, but there was once a time when President George W. Bush enjoyed a sunset dinner on a yacht with Vladimir Putin as they floated through St. Petersburg. Over caviar and foie gras catered by the now-deceased Yevgeny Prigozhin, they toasted to Russia’s European future and the potential for partnership between their two great states.

But the days of diplomatic river cruises are over, not least because Putin’s yacht is languishing in an Italian harbor after it was seized under sanctions imposed for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. What happened?

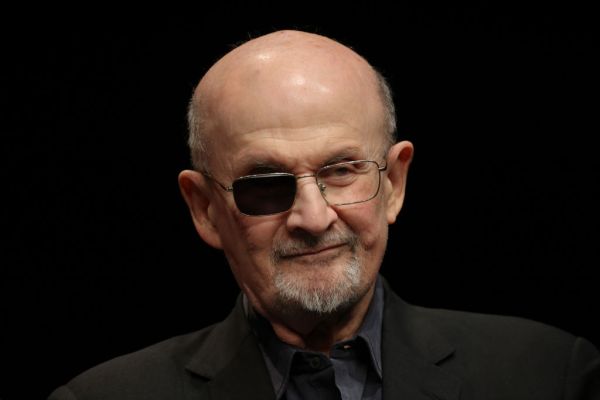

New Cold Wars by David Sanger explores the United States’ evolving relationships with China and Russia since the Bush administration, with a particular focus on the Trump and Biden years. Sanger, the longtime White House and national security correspondent for the New York Times, places the reader in the middle of the most critical American foreign policy moments of the past 10 years. Yet his account is descriptive, not prescriptive. New Cold Wars is less a policy treatise and more an accounting of the particular events and people that shifted the consensus on China and Russia policy in Washington.

As the title implies, New Cold Wars takes up the debate over “great power competition” with China and Russia. In the Bush and Obama years, the “overwhelming orthodoxy” was that eager engagement and economic interdependence with China would lead to political and economic liberalization and peaceful coexistence in the U.S.-designed international order. In Sanger’s telling, that orthodoxy gave way to a harsh realization that China and Russia are eager to challenge the United States directly in service of their own economic, geopolitical, and authoritarian aims.

This new consensus was partially driven by former President Trump’s campaign promises to redefine America’s relationship with China by addressing the trade deficit and punishing China’s currency manipulation. But the shift was broader. You won’t hear it shouted from the rooftops in our divided politics, but policy strategies initiated under Trump were tweaked and expanded by the Biden administration. Sanger rightly credits the Trump administration for initiating many of America’s signature policy responses to China that came to fruition under Biden, such as export restrictions on critical technologies, and heavily investing in scientific research and domestic semiconductor chip manufacturing.

To be sure, most of these strategies were driven by working-level officials and not the former president himself. As Sanger writes, “It was the Trump administration that identified China as having a long-term plan to displace the United States as the world’s dominant power … But the president’s own ego, his inability to focus on strategy, and his habit of undercutting policy for his own personal gain also stymied the efforts.” It took a concerted effort under the Biden administration to negotiate the CHIPS Act, invest in Pacific allies, and protect supply chains critical for national security.

Sanger also chronicles Washington’s dawning realization that American economic and foreign policy hinges on the role of private companies more than ever before. In one particularly engaging chapter, Microsoft’s cybersecurity professionals notified the White House that they were watching live as Russia launched massive cyberattacks preceding their ground invasion, hours before the U.S. government could see tanks rolling across the Ukrainian border. While this has been the topic of white papers and panel discussions for years, Sanger ties it together as one coherent and compelling narrative. As one senior official told Sanger, the future of national security is one in which “companies have all the insight.”

As a result, the private sector is on the front lines of cyberwarfare, corporate espionage, and industrial policy. Private defense tech companies like Anduril, Starlink, and Palantir have revolutionized drone technology, satellite internet networks, and intelligence and data visualization. If history is any indication, Americans will have consumer applications for many of these technologies in the coming years.

While Sanger’s prominence as the New York Times’ White House correspondent gave him unparalleled sourcing, it may have contributed to an overemphasis on the executive branch and the decisions of a small circle of officials. Congress’ role in foreign policy and budgetary authority was barely covered, and there was little discussion of perspectives outside of elite power circles in all three states. Sanger’s account told us how we got here, but without discussing domestic politics and shifting public opinion it’s hard to understand where America’s relationships with China and Russia will go in the future. Even in China and Russia, where power is centralized under authoritarian executives, the state works hard to legitimate itself and build national narratives to support its foreign policy.

Sanger omits, for example, negotiations over aid packages to Ukraine and Taiwan and the progressively slimmer margins by which they’ve passed since 2022. In the wake of the Republicans’ recent electoral victory, it remains to be seen whether Trump’s desire to reshape key alliances and force a quick political settlement in Ukraine will shape American public opinion. As of this summer, 57 percent of Americans support continued economic and military aid to Ukraine, though that majority is steadily declining. New Cold Wars was published in April 2024, so the emerging impact that the wars in Gaza and Lebanon have had on American foreign policy only makes it into the epilogue. One can hardly blame Sanger for the timing, and his narrative is still useful in helping us understand the strategy that the new Trump administration will be inheriting.

For such a well-researched and nuanced book, the title’s Cold War framing seems reductionist. As Jonah Goldberg recently argued about a similar Cold War framing by the historian Niall Ferguson, “using the prism of the original Cold War misleads more than it illuminates.” But the Cold War language is useful insofar as it reminds the reader that great power competition could become all-encompassing of our attention, resources, and political rhetoric. That’s precisely what makes it so dangerous and difficult. The opportunity costs of total competition with China and Russia are immense. At the end of the original Cold War in the 1990s, the United States benefited from a “peace dividend” that freed up funds for investments in housing, education, and other civilian projects to create economic growth. More recently, European governments have had to make difficult choices to increase their defense spending to counter the threat of their Russian neighbor.

However, it’s undeniable that the United States is in competition on a host of issues. As Sanger documents, many American officials have lost their rosy view of the power of economic liberalism, free trade, or even personal relationships between leaders to influence the behavior of authoritarian states, regardless of what the leaders themselves claim they can do.

Out of that reality, readers and policymakers are left with a question: Which of China and Russia’s challenging actions merit a competitive response? And which are within the bounds of expected foreign policy, with room for cooperation on shared objectives? Sanger doesn’t draw those lines for readers, but they’re in good hands as he inevitably reports on the policymakers that do.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.