Hey,

Let me start by saying, I have boundless respect and admiration for my friend, the acclaimed historian Niall Ferguson. He’s flat-out brilliant and more knowledgeable about more stuff than almost anybody I know. So, of course, I’m jealous that our friends at The Free Press picked him up as a columnist. Good for him, them, everybody.

But … you knew there had to be a but.

His debut column for the Free Press is … off. I’d say it’s disappointing, but that’s not quite the right word because I got a lot out of it. It’s vintage Ferguson, brimming with interesting insights, facts, and more than one dyspeptic I-told-you-so.

Maybe it’s because he spent so much time working on Henry Kissinger’s biography, or because he wrote a book called Doom, but there’s a good deal of gloominess (or dreich, since he is Scottish) in Niall’s writing these days. That’s somewhat justifiable, of course, in that he’s kind of a corporeal manifestation of the admonition not to forget history lest it bite you in the ass (I’m paraphrasing the more familiar quote).

So while his Tuesday essay is vintage Ferguson, I think it suffers from what often happens to great vintages: Every now and then one of the bottles turns on you, coming out darker and more acidic than it should.

Ferguson compares the United States today to the Soviet Union, arguing that we live in “late Soviet America.” The comparison is not as crazy as I thought it was before I started the essay, but for all his marshaling of data and facts to sustain the analogy, he fails to avoid the bitter aftertaste of a corked bottle.

There are numerous areas where I am in complete or near-complete agreement with Ferguson’s descriptions of America’s problems. Looking at the data around suicides, overdoses, and other “deaths of despair,” there’s no sugarcoating the very real problems facing parts of our society. His description of the folly of making climate change the driver of so much of our political—and politicized—economy amid our geostrategic competition with China; his condemnation of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) commissars; his contempt for the misbegotten views of progressive elites; his criticisms of our healthcare system and our military (un)preparedness. All of these claims resonate with me to a considerable degree. (I think the depiction of our military as something of a paper tiger is overstated, though, as evidenced by the success of our weapons systems in Ukraine and Israel).

My problem is with his analogy. We are not like the Soviet Union—at least not in most of the ways that matter most.

Since I am so uncomfortable picking a fight with Niall, I’ll start with what I consider the most defensible aspect of the comparison: America on the world stage. Niall was an early proponent of the idea that China had replaced the Soviet Union as a geopolitical rival in a new cold war. My position on such claims is nuanced. I agree we are in a kind of cold war with China, but I think there are far fewer direct parallels when it comes to the old, capital-C Cold War with the Soviet Union. The global “communist struggle” played a very different political, cultural, and psychological role on the world stage—and, crucially, in American domestic politics—than whatever we’re supposed to call China’s model.

Niall has a slightly different take. “China is clearly not only an ideological rival, firmly committed to Marxism-Leninism and one-party rule,” he writes. “It’s also a technological competitor—the only one the U.S. confronts in fields such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. It’s a military rival, with a navy that is already larger than ours and a nuclear arsenal that is catching up fast. And it’s a geopolitical rival, asserting itself not only in the Indo-Pacific but also through proxies in Eastern Europe and elsewhere.”

I agree with all of this, except for that first sentence. China is certainly a rival with a different ideology, but I don’t think that ideology is Marxism-Leninism—and neither, by the way, does Xi Jinping. He had all references to Marxism-Leninism removed from the State Council’s rulebook last year and replaced with Xi Jinping Thought. The Communist Party’s charter was similarly revised so that Xi Jinping Thought is now officially “the essence of Chinese culture and the spirit of the times.” I simply don’t think that Xi Jinping Thought lights fires in the minds of Western Intellectuals and other useful idiots the way Marxism did in the 20th century. I’m sure there are some true believers among Westerners who’ve betrayed us for China, but from what I can tell most of them have been motivated by greed, not misplaced idealism.

That doesn’t mean talk of a new cold war is wrong, but I think using the prism of the original Cold War misleads more than it illuminates. Niall is right that China is a very serious competitor militarily, just as the Soviet Union was. But the Soviet Union really wasn’t an economic or technological competitor the way China is. So, asking “How did we handle the Soviets?” doesn’t offer a lot of useful answers. Detroit was not worried about the Soviets flooding the American market with crappy cars. IBM did not sweat the threat of Russian-made computers to their bottom lines.

But one aspect of the Cold War analogy does have useful explanatory and analytical power: Great power rivalry. Niall writes:

The question that haunts me is: What if China has learned the lessons of Cold War I better than we have? I fear that Xi Jinping has not only understood that, at all costs, he must avoid the fate of his Soviet counterparts. He has also, more profoundly, understood that we can be maneuvered into being the Soviets ourselves. And what better way to achieve that than to “quarantine” an island not too far from his coastline and then defy us to send a naval expedition to run the blockade, with the obvious risk of starting World War III? The worst thing about the approaching Taiwan Semiconductor Crisis is that, compared with the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the roles will be reversed. Biden or Trump gets to be Khrushchev; XJP gets to be JFK. (Just watch him prepping the narrative, telling European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that Washington is trying to goad Beijing into attacking Taiwan.)

I can find some things to quibble with here, but overall, this is a very thoughtful and worrisome insight.

This part of Ferguson’s analogy works because the international realm is different than the domestic realm. States compete and transact according to different rules because there are no formal and binding rules in Great Power conflicts. To be sure, there are agreements, alliances, treaties, best practices, and even this thing called “international law.” But at the end of the day, compliance with these things is wholly voluntary. That doesn’t mean there aren’t—or shouldn’t be—consequences for violating such expectations, but there is no court or “state” that can enforce them the way a government can enforce the rules within its own borders.

“The Pope? How many divisions has he got?” Joseph Stalin is alleged to have said. The answer is … the same number as the United Nations and the International Criminal Court. The state, as Max Weber famously argued, is the “human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.” No entity has such a monopoly on the world stage.

And that’s why the analogy has explanatory power. Regardless of what we thought of the Soviet Union’s internal system, it was a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. George Kennan’s take on the USSR was that as a world player, it made many of the same calculations of its vital interests that Czarist Russia did—and came to the same conclusions. Whether in fact Czars and Bolsheviks alike loved warm water ports or not, the idea was that they did. This sort of thing was a useful insight for military planners and statesmen, who did not have the luxury of letting too much idealism influence the deployment of ships and missiles.

In other words, Ferguson’s Cold War analogy works in the international realm because the internal ideology of states doesn’t necessarily determine how we should think about the competition between states in the realm external to our borders. If North Korea didn’t have a nuclear program, we’d probably spend as much time thinking about it as we do Burma.

If all Niall was saying is that as a matter of geostrategic competition, we are repeating some of the mistakes the Soviets made, I’d have no major objection. I’m not sure it’s the ideal analogy, but it’s not implausible or offensive either.

But like a carriage hitched to a wild horse, he lets his analogy drag him off the path and into a ditch. America is simply not like the Soviet Union. Again, do we have problems that have some superficial similarities with the Soviets? Sure. But … come on.

Conceding his parade of horribles—deaths of despair, runaway debt, sclerotic government—does not undermine my objection. For starters, the Soviet Union built a wall to keep its subjects trapped inside their evil empire. Many Americans understandably believe we need a wall to keep millions of people desperate to live here out. When interviewed while illegally crossing the border, many of these people sound more patriotic and pro-American than many of the people demanding that they be kept out. That alone is a testament to the fact that, for all of the United States’ problems, this country is dealing with qualitatively different issues than those that bedeviled the Soviet Empire.

Indeed, many of the problems we face come from the opposite direction. One of the reasons the Soviet Union collapsed was that it was so afraid of the free flow of information that it chained up its photocopy machines at night, lest some dissident sneak into the office or the library and run copies of samizdat. Say what you will about the pathologies unleashed by social media; a lack of access to communication technology isn’t the driver of them. And whatever you make of the “censorship” wars, shadow-banning and content moderation is not the same thing as Soviet oppression.

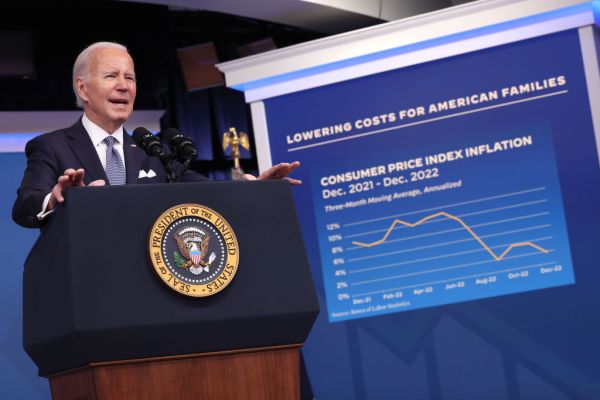

I agree with many of Niall’s observations about our fiscal and economic challenges, but they are also completely different than those the Soviets faced. “The U.S. economy might be the envy of the rest of the world today,” Niall writes, “but recall how American experts overrated the Soviet economy in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Come on now. Niall knows, better than I, that those “experts” were mostly outliers and that they were objectively wrong about the Soviet Union. More importantly, the reason they were wrong was that they were ensorcelled by a kind of power-worship about the Soviet Union. Those experts, most of whom resided in the Ivory Tower, were letting the wish be the father of the thought.

America remains the top recipient of foreign direct investment for reasons that have little to do with ideology. Capital markets, not to mention millions of migrants, are not making ideology-driven calculations about the American economy. The proof that America’s economy has been an unrivaled success story can be found in hard data and the staggering wealth of the American consumer, not the equivalent of Soviet propaganda about banner wheat harvests.

As someone with an obsessive interest in the intellectual history of the “new class” and a healthy disdain for “DEI” mongering, I have considerable sympathy for Niall’s problems with what he dubs the American nomenklatura of elite bureaucrats and other members of the managerial class. That said, his comparison between the American new class and the Soviet new class is missing a vital moral element.

In the Soviet Union, the new class secured its power with actual force—and occasional terror—from above. As harsh as the consequences might be for crossing the HR department or the campus diversity officer, such transgressions do not result in banishment to Siberia, never mind a bullet to the back of the head. Such hyperbole overlooks major differences, not just in degree but in kind. Things could get a lot worse on all the fronts Niall describes without even encroaching upon the parking lot of the same ballpark as the Soviet Union.

Ferguson makes a similar error in describing Donald Trump’s fate in a New York courtroom as “Soviet Justice.” He doesn’t make the oft-repeated claim that the former president has been subjected to a Stalinist “show trial,” but he’s certainly nodding toward it. And that’s offensive nonsense.

New York’s prosecution of Donald Trump was politically motivated, and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s legal case was weak. Granted. But Trump was not detained in a “torture dacha” pending trial, and his family wasn’t threatened with execution or prison. The former president complained that the courtroom was too cold, but he didn’t complain about being required to stand in a bent position with his hands behind his back. Needles were not shoved under his fingernails, nor were his hands slammed in door frames. He was not told, “If you don’t sign a confession, we’ll go on beating you. We’ll leave your head and right hand alone, but we’ll turn the rest of you into a shapeless bloody lump of meat.” When the guilty verdict came in, he was released on his own recognizance to campaign for president or bask in his non-alcoholic crapulence in Mar-a-Lago. He wasn’t taken out back, along with his family, and executed.

Now, if you want to make the case that the way Trump has been treated is reminiscent of some banana republic, we can debate the merits of that analogy. In fact, I would proactively argue that there are banana republic-ian elements to Trump’s travails—but the analogy works both ways. Trump is running in no small part to avoid criminal prosecution, and his defenders who shriek about banana republic justice are making banana republic arguments themselves when they suggest their preferred demagogue be held immune from equal justice because he’s the avatar of their populist movement. But that is all beside the point, because none of this looks remotely like the politics or the “justice” system of the Soviet Union.

This is the problem with holding onto analogies and metaphors too tightly. They end up as Christmas trees, upon which you hang cheap ornaments alongside the quality ones in the hope no one will be able to tell the difference.

George Orwell wrote about this tendency in Politics and the English Language. We often let cliches, metaphors, and turns of phrase drive us to intellectual destinations unsupported by reality, until “prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house” that end up doing your thinking for you. Again, an essay about how America is repeating some of the Soviet Union’s mistakes in our rivalry with China has real merit. Tacking on campus inanity, obesity, budget deficits, or Trump’s travails detracts from that argument rather than bolstering it.

The reason this matters so much to me is that the “new right” is starting to look like the old new left in its fundamental—in the truest sense of the word—opposition to the American project. It was once common for left-wing critics to compare America to the Soviet Union, unfavorably, or to argue for a “moral equivalence” between the U.S. and USSR. When Niall Ferguson, one of our best intellectuals, lends aid and comfort to such arguments, I feel compelled to confront, contest, and hopefully correct it—even if I take little pleasure doing so.

Ronald Reagan was right when he described the Soviet Union as an evil empire, because it was evil and it was an empire. America, for all its faults, is neither. And even if you think, as some do, that America is an empire, the nature of our empire is profoundly, morally, superior to the Soviet Empire. Our NATO allies have a choice to join—or leave—our alliance. The Warsaw Pact? Not so much. You could argue that Finland and Sweden joined NATO at gunpoint—but we weren’t the ones pointing the guns.

There was no moral equivalence between the United States and the Soviet Union then, and there isn’t any now, either. One simple way to illustrate this: The problems of the late Soviet Union would have only been compounded if it returned to its founding principles. But we would go a long way to solving the problems facing “late Soviet America” if we reasserted ours.

There was a time when this was a matter of fundamental conservative dogma, and, as Niall’s Free Press colleague Douglas Murray recently reminded us, that’s a thing worth remembering. As William F. Buckley quipped: “To say that we and the Soviet Union are to be compared is the equivalent of saying that the man who pushes the old lady into the way of an oncoming bus, and the man who pushes the old lady out of the way of an oncoming bus, are both people who push old ladies around.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.