There is little question that Democrats are in the midst of rediscovering the benefits of federalism. In the weeks after the seismic shock of the 2024 election, The Atlantic’s Franklin Foer found blue state governors and policy wonks busy framing “a new progressive vision of federalism” that could move their priorities forward despite the defeat. Creativity has since taken a back seat to resistance as blue states have challenged executive orders on multiple fronts, from birthright citizenship to transgender athletes. It might be only a matter of time before we start hearing speeches about states’ rights from California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

So far, though, no blue states seem to have contemplated using federalism’s nuclear option: the controversial constitutional theory known as nullification, which holds that a state can unilaterally declare a federal law unconstitutional and refuse to enforce it. As a constitutional theory, nullification has never been widely accepted as legitimate. The most famous examples of its use suggest that it is a tactic used by Southern states to resist federal power, often in situations involving race. But the actual history of the idea shows that it has been a much more flexible, common, and bipartisan tactic than its popular image suggests.

The idea has seen a resurgence in recent years, and not only on the right. In this respect, the Trump administration is tempting fate. Earlier this year, President Donald Trump invoked the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to deport immigrants while circumventing normal processes, and then imposed a series of eye-popping tariffs that tanked the stock market. These two measures share an interesting historical connection: Both the 1798 law and tariffs provoked early standoffs between states and the federal government in which states claimed the right to nullify an unconstitutional federal law. Could it happen again? Is it already?

Nullification was born in the 1790s in a political landscape that doesn’t map easily onto our current definitions of right and left. On one side, the Federalists favored a strong national government, epitomized by Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan, and feared that the democratic excesses of the French Revolution might find their way to American shores. On the other, the Democratic-Republicans, led by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, reviled Hamilton’s plan as a blueprint for tyranny and saw the French Revolution as a legitimate if unruly heir to the American one. During the Quasi-War with France in 1798, fearful of foreign agents and stung by domestic critics, a Federalist-dominated Congress passed and John Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, allowing the deportation of “alien enemies” and the prosecution of any citizen who published “false, scandalous, and malicious writing" about Congress or the president. Eventually, several Democratic-Republican newspaper editors and even a sitting congressman, Matthew Lyon of Vermont, would be prosecuted under the Sedition Act.

In response, Jefferson and Madison sketched the outlines of an enduring strategy for resisting federal power. In resolutions passed by the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures, written by Jefferson and Madison, respectively, the two men argued that the Constitution was a “compact” between sovereign states and that, as parties to that compact, states had a role to play in judging the constitutionality of federal laws. It was a recipe for tyranny, the resolutions argued, to allow the national government to pass judgment on the extent of its own powers.

There was a key difference between how Madison and Jefferson described the actions states should take. In the Virginia resolutions, Madison argued that “in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact,” a state had a duty “to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil.” Madison was clearly concerned with affirming the legitimacy of the Constitution and the federal government. He wanted states to work together within the system to resist federal overreach.

In his original draft of the Kentucky resolutions, Jefferson went further. “Where powers are assumed which have not been delegated,” Jefferson wrote, “a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy.” Jefferson did not outline how nullification could be carried out, but he asserted that states had a “natural right” to nullify a federal law and declared the Alien and Sedition Acts “void, and of no force” in the state of Kentucky. (The legislature chose to omit the word “nullification” in the final language.) Compared to Madison’s more tactful notion of state interposition within the constitutional framework, Jefferson’s idea of nullification resembled a revolutionary act justified by natural right. The difference, as history would show, mattered.

“Despite its long, sometimes unsuccessful, and morally checkered history, the idea of nullification has never truly died because its taproot is sunk in the same soil that sustains our instinct for nationalism, democracy, and the freedom of the individual from social or political coercion—the principle of self-determination.”

Historians once assumed that the arguments contained in the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions were quickly and universally dismissed, but only a few Federalist-dominated states in New England condemned the resolutions outright. Legal scholar Wendell Bird has shown that at least half of the states, many in the South, either supported or deliberately stayed silent on them. Jefferson and Madison’s robust defense of freedom of the press and speech, as well as their argument that states had a duty to defend those rights for their citizens, were more broadly accepted than we previously thought.

Indeed, less than 20 years later, states that had condemned Jefferson and Madison’s resolutions were making some of the same arguments—against Madison himself, who became president in 1809 and oversaw the second war against the British. By 1814, the British had burned Washington to the ground, and the Madison administration’s wartime trade restrictions were decimating New England’s shipping industry. Noah Webster, the father of the famous dictionary and a prominent Connecticut Federalist, later recalled, “our shipping lay in our harbors embargoed, dismantled, and perishing; the treasury of the United States was exhausted to the last cent; and a general gloom was spread over the country.”

Delegates from across New England met in Hartford, Connecticut, in December 1814, passing a series of resolutions protesting what they considered unconstitutional actions by the Madison administration. The resolutions infamously raised the specter of secession but also included measures far short of that—new amendments to the Constitution and the right of states to interpose their authority to protect their citizens from the federal government. “That acts of Congress in violation of the Constitution are absolutely void, is an undeniable position,” the report declared in words calculated to remind Madison of his own position in 1798. The delegates concluded that in instances “affecting the sovereignty of a State, and liberties of the people; it is not only the right but the duty of such a State to interpose its authority for their protection.”

Held mere weeks before news of a peace treaty and Andrew Jackson’s miraculous victory over the British in New Orleans, the Hartford Convention would be remembered as a political disaster for the Federalists. Still, the report produced by the delegates shows that in the early years of the republic, the idea that a state could somehow protect its citizens from an unconstitutional law was embraced on both sides of the aisle, although only when their party was out of power.

From the beginning, the central problem for those invoking the idea of state interposition has been that it appears nowhere in the Constitution. The idea was born in the murky gaps between state sovereignty and national authority that remained after ratification. Added to this was the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal court system and, in its famous 25th section, established the Supreme Court as the ultimate arbiter of any state court decisions that involved constitutional interpretation. Affirmed by an important Supreme Court case, Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, in 1816, the 25th section of the Judiciary Act became a thorn in the side of anyone trying to frustrate federal power with appeals to state sovereignty. To critics, making the federal government the final arbiter of its own powers was like putting the federal fox in charge of the henhouse full of states.

Still, for three decades after Jefferson first invoked the idea of nullification, no state actually tried it. That changed in 1832, when a convention called by the South Carolina legislature declared a tariff bill passed by Congress null and void. The resulting crisis changed the course of American history, narrowing, for a time, the range of responses that states could take to resist federal actions and forever painting nullification with the colors of political radicalism.

South Carolina’s case against the 1828 “tariff of abominations” was that it aimed at the protection of specific industries rather than simply raising revenue as the Constitution allowed. The tariff sought to protect New England textile manufacturers from larger and more efficient English competitors and was part of a national economic vision of a “home market” advocated by Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky. But, as opponents like Sen. George McDuffie of South Carolina never tired of pointing out, it was Southern consumers, not Northern producers, who bore the brunt of the tariff. To the minds of many South Carolina cotton planters, who exported their crops and imported everything else, the tariff was nothing more than an insidious mechanism of wealth redistribution.

South Carolina planters also saw in the tariff a looming threat to slavery at a time when it was under threat across the Western Hemisphere. Great Britain would abolish slavery throughout much of its empire in 1833. Domestically, the Nat Turner rebellion and the massive so-called Baptist War in Jamaica unfolded just months before South Carolina nullified the tariff, putting the entire South on edge. After all, if the federal government could pass a tariff that disadvantaged Southern states without their consent, slaveholding South Carolinians reasoned, there was nothing to stop it from eventually abolishing slavery.

Nullification had many fathers, but its architect was South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, Andrew Jackson’s vice president. Convinced the tariff was unconstitutional, Calhoun put flesh on the bones of Jefferson’s old theories in an attempt to find an elusive middle ground. Calhoun first articulated his theory in an anonymous exposition passed by the South Carolina legislature in 1828, and then in the Fort Hill Address, which became an urtext of the states’ rights movement. His main innovation was the argument that nullification must be done by a convention of the people of a state, not by the state legislature or state courts. The convention represented the purest and most direct representation of the people’s will, but it would also be difficult to contest through the courts, sidestepping the troublesome Judiciary Act. The convention approach echoed Jefferson’s contention that nullification was a natural right flowing from the ultimate authority in a democracy—the people.

The main objection to nullification, Calhoun knew, was that allowing states to pick and choose which laws to follow would produce constitutional chaos. Eager to counter this objection and to smooth nullification’s revolutionary edge, Calhoun argued that one state’s nullification of federal law should trigger conventions in every other state. If three-fourths of the states approved the central government’s actions, these conventions would amend the Constitution to grant the federal government the powers it asserted. Conversely, if less than three-fourths of the states approved the law, not only would the nullifying state emerge victorious, but the law would be declared null and void for all states. An aging James Madison considered Calhoun’s carefully and forcefully argued case for nullification so dangerous that he issued a public response, calling the idea “a fatal inlet of anarchy.”

South Carolina tried it anyway. In November 1832, the South Carolina legislature called a convention that declared the tariff “null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this State.” It also forbade federal officials from enforcing the tariff and declared that any attempt to administer the tariff by force would be “inconsistent with the longer continuance of South Carolina in the Union.” In other words, secession.

The parallels between Donald Trump and Andrew Jackson are both undeniable and illusory since history rarely provides solid ground for predictions. But if we want a historical analogue to what might happen in a similar situation today, we should keep Jackson’s response to nullification in mind. In a public statement to the people of South Carolina, Jackson gave what would become the most popular critique of nullification, dismissing as self-evidently ridiculous a theory that “permits a State to retain its place in the Union and yet be bound by no other of its laws than those it may choose to consider as constitutional.” More controversially, Jackson asked Congress to give him the power to invade South Carolina to enforce the tariff. For good measure, he hinted that if he invaded, he would hang the nullifiers. John C. Calhoun prudently resigned as vice president, and South Carolina started raising troops to defend against an invasion.

Only a carefully orchestrated compromise averted civil war. After several weeks of tense standoff, Congress passed Jackson’s so-called Force Bill alongside a new compromise tariff, engineered by Calhoun and Henry Clay, that gradually decreased tariff rates over 10 years.

The standoff between South Carolina and Andrew Jackson forever associated the idea of nullification with radicalism. However, in the 1840s and 1850s, with slaveholders ascendant in national politics, Northern states once again found themselves at odds with the national government. During the 1840s, Northern states, outraged by slaveholders’ attempts to recover fugitive slaves, passed what were known as personal liberty laws, prohibiting state officials from assisting private or federal efforts to reclaim fugitive slaves. Hoping to avoid the label of nullificationists, these states chose strategies and rhetoric more in keeping with James Madison’s idea of interposition than with Jefferson and Calhoun’s nullification. In an era when the federal government had few boots on the ground, personal liberty laws effectively rendered the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause and the 1793 law intended to enforce it null and void, although without the public drama and provocation of a nullification convention. As Andrew Delbanco put it in his recent book on these laws, Northern states effectively told the federal government, “Do your own dirty work. We won’t help.”

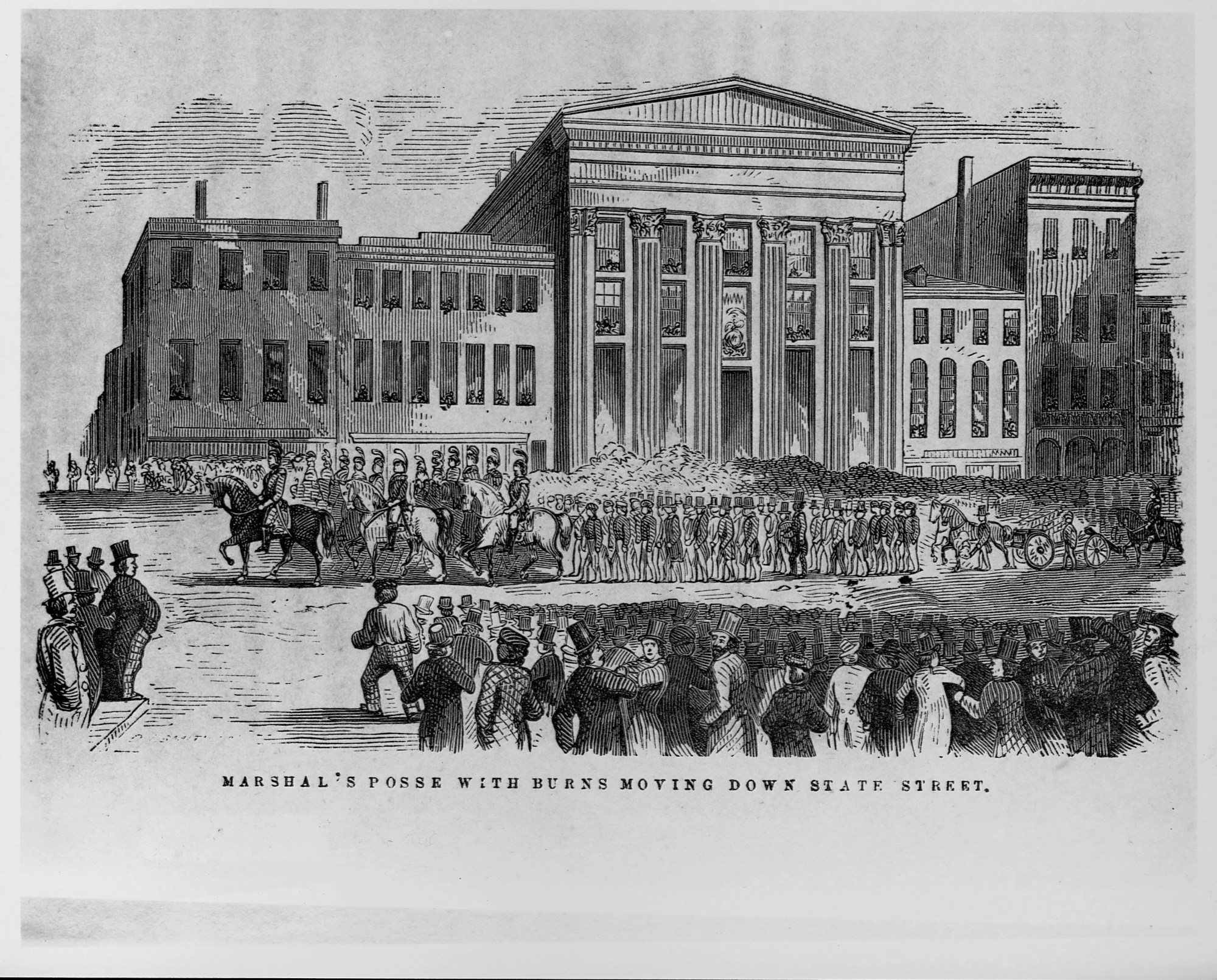

The personal liberty laws soon became one of the central complaints of slaveholders, who saw them as nothing but nullification by another name. If it had been unconstitutional for South Carolina to do it, Southern states argued, it was unconstitutional for Massachusetts, too. This led to the passage of an even more stringent Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which put the full power of the federal government at the service of slaveholders attempting to recover runaways. By the time the Civil War broke out, as Eric Foner recently noted in his prize-winning book on Abraham Lincoln and slavery, some Northern states were openly advocating nullification. In 1859, the state of Wisconsin declared a Supreme Court decision upholding the law “without authority, void, and of no force” in the state, and a Republican politician admitted that to resist the law, “we have got to come to Calhoun’s ground.” The political polarity of nullification had flipped again.

As a result, many of the secession ordinances passed by state conventions in 1860 and 1861 cited the effective nullification of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause, as well as the 1793 and 1850 laws, as one of the primary reasons for withdrawing from the Union. South Carolina’s secession ordinance complained that Northern states “have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them.”

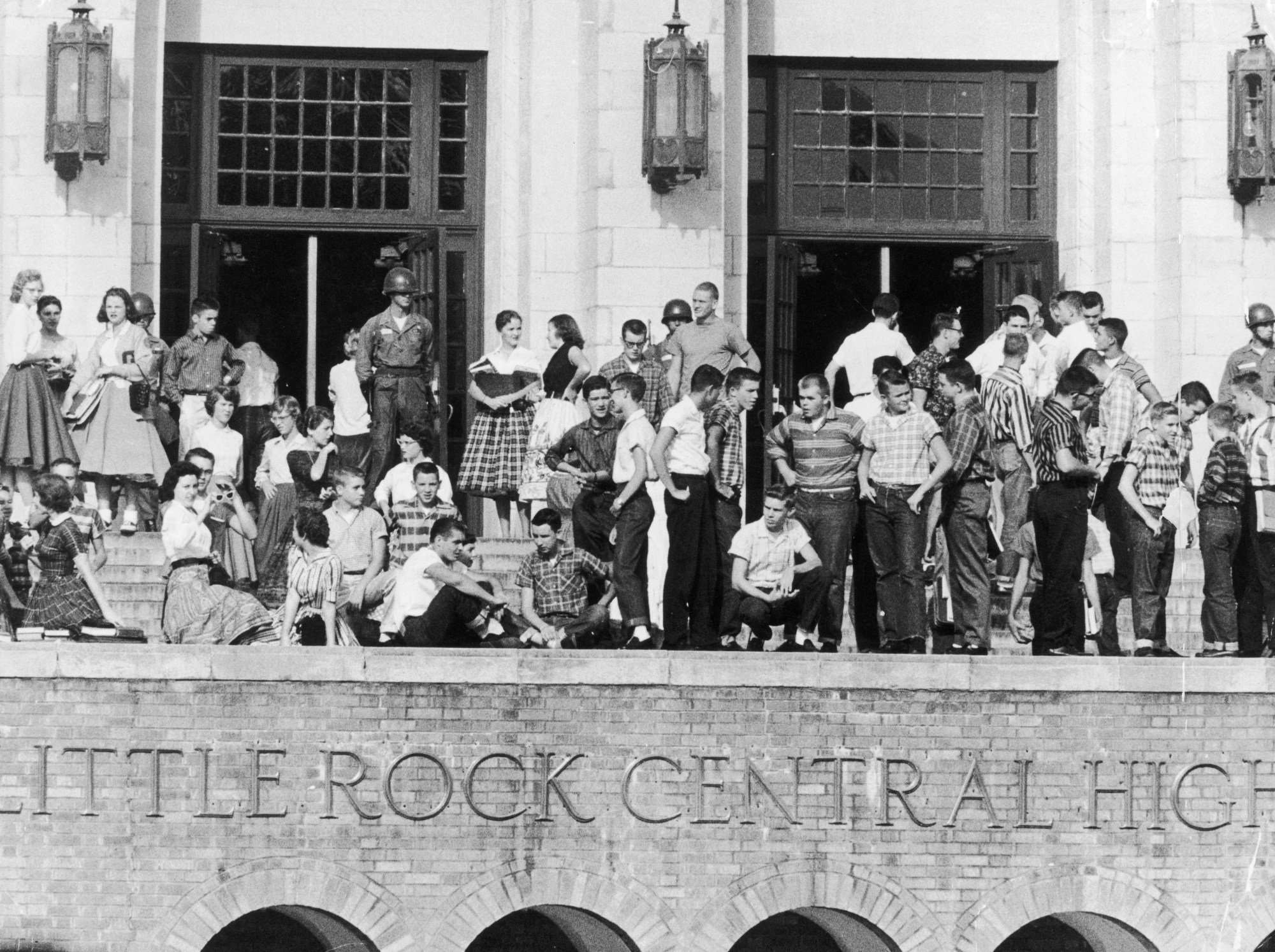

After the Civil War and the Reconstruction amendments remade the relationship between the federal government and the states, it seemed that nullification was dead. Events proved otherwise. The most significant 20th-century resurgence of the idea came in response to the civil rights movement, and especially the seismic 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision. In a series of editorials, a young newspaper editor for The Richmond News Leader named James J. Kilpatrick recommended Madison and Jefferson’s solution to Southern states searching for ways to resist the ruling. In Congress, a group of Southern senators led by Virginia’s Harry Byrd and South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond penned the so-called Southern Manifesto, declaring the Brown decision unconstitutional and calling for state resistance.

Several Southern states soon passed interposition resolutions. Although they carefully avoided the politically loaded term “nullification,” they clearly meant to invoke it. Alabama’s resolution, for instance, declared the decision “null, void, and of no effect.” Significantly, these resolutions were passed by state legislatures, not constitutional conventions, as Calhoun had once recommended.

It was another Supreme Court case that seemed to put the nail in neonullification’s coffin. In the 1958 decision Cooper v. Aaron, the Supreme Court explicitly took aim at the idea of interposition, declaring that attempts by the governor and state legislature of Arkansas to “nullify” the implementation of their 1954 Brown decision were unconstitutional. Issued as a unanimous opinion—bringing the full weight of the court to bear—Cooper v. Aaron asserted that the Constitution, as interpreted by the federal judiciary, was the supreme law of the land and could not be thwarted or evaded by the action of any state official or legislature. Intended to prove the court’s determination to desegregate American schools, Cooper v. Aaron read as if it were written to vindicate the fears of critics during the early republic who mocked the idea that the federal government could determine the extent of its own powers as the very definition of tyranny. But at least for the moment, the specter of nullification faded.

Despite its long, sometimes unsuccessful, and morally checkered history, the idea of nullification has never truly died because its taproot is sunk in the same soil that sustains our instinct for nationalism, democracy, and the freedom of the individual from social or political coercion—the principle of self-determination. To see the connection, and to fully understand the possibilities of the moment we live in, one only needs to glance at the growing global acceptance over the last century of another idea that most Americans still find controversial: secession. From Catalonia to Kurdistan to Quebec, the claims of linguistic, religious, political, or ethnic minorities to a separate national identity are taken more seriously today than they once were, even when they are ultimately unsuccessful. The change has to do with the increasing gravitational pull over the past century of the lodestar of self-determination, as applied to individuals as well as breakaway states.

It should be no surprise, then, that nullification, too, seems poised for a repeat performance. In 2010, two years into the first Obama administration, the right-wing radio talk show host Tom Woods published a book titled Nullification: How to Resist Federal Tyranny in the 21st Century. In 2012, political scientists James Read and Neal Allen drew attention to several recent bills, most of which eventually failed, that employed the language of nullification. A bill passed by the Idaho House of Representatives declared Barack Obama’s Affordable Health Care Act “void and of no effect” in the state, a deliberate echo of Jefferson’s 1798 Kentucky Resolution. A similar bill in North Dakota passed both houses and was signed into law by the governor, although only after explicit references to nullification were removed. In 2013, the Kansas legislature declared that federal firearms laws did not apply within the state and included criminal penalties for federal officials who attempted to enforce federal gun regulations. Signed into law by Republican Gov. Sam Brownback, the bill prompted a sharp retort from Attorney General Eric Holder, but it remains on the books like a burning fuse.

Yale Law School professor Jack Balkin termed the revival of nullification “zombie constitutionalism.” In January 2023, more than 50 people in blue T-shirts with the word “NULLIFY” printed across the front gathered at the South Carolina statehouse to urge state lawmakers to pass the South Carolina Sovereignty Act to bar the Biden administration’s policies. “We have to do as our forbearers did and reject tyranny,” Rep. Josiah Magnuson told the crowd to applause. Clearly, nullification is back.

Today, some on both the right and the left have seen a revival of nullification, or at least state interposition in some form, not as a troubling symptom of our division but as a possible solution. In his 2020 book American Secession, the conservative legal scholar Frank Buckley proposed nullification as a “secession lite” alternative to national disunion. Meanwhile, Heather Gerken, the dean of Yale Law School, is one of the leading proponents of the self-proclaimed “nationalist federalists,” a group of progressive legal scholars who see a renewal of robust and rowdy federalism as a path forward at a dangerous moment in our history and a crucial way to originate new rights within our constitutional framework. Noting that it was states, not the federal government, that led the way in legalizing gay marriage, Gerken applauds what she calls “uncooperative federalism” as a mechanism for holding different levels of democratic governance in tension with one another in situations where local and state majorities may differ from national ones. “Uncooperative federalism may sound antithetical to certain legal values,” she writes, “but it’s not antithetical to democratic ones.”

While there is little distinction on the ground between how red states and blue states have practiced neonullification in this new era—both aim to frustrate federal law—there is a difference for now in how they talk about it. Red states resisting federal legislation during the Barack Obama and Joe Biden administrations did not shy away from using language crafted by Jefferson, Madison, and even Calhoun, declaring federal laws null and void within state boundaries, even if they mostly failed to follow through on those threats.

In contrast, blue states have carefully avoided the terminology used by red states while pursuing what are in practice often more effective strategies of resistance and simple noncompliance that make a federal law unenforceable. In some cases, the noncompliance is active, as when Colorado legalized marijuana in 2012 in defiance of federal law. In others, blue state laws like the 2017 California Values Act, which prohibits state and local law enforcement from enforcing federal immigration law, hark back to the personal liberty laws passed by many Northern states in the 1840s forbidding state officials from aiding federal efforts to recover fugitive slaves.

With the Trump administration determined to tempt fate by invoking some of the exact laws and policies that provoked nullification in the first place, and their citizens desperate for avenues to resist the onslaught of executive orders, will mere uncooperative federalism be enough for blue states? As Republicans have become increasingly comfortable with the exercise of federal authority, especially presidential powers, they’ve abandoned old arguments for states’ rights and federalism, leaving those venerable American political weapons available for use. Democrats and blue state officials have employed some of them already. Nullification—the “null and void” kind—is one of the most unpredictable and dangerous weapons in that arsenal, but it’s a hand grenade that history suggests can be thrown from either side of the aisle. Will blue states pull the pin?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.