Dictatorships make you sick. Not spiritually, not morally (though both may apply), but actually sick. Consider the responses to coronavirus by China and Iran, two authoritarian regimes whose rank mismanagement and compulsion to cover-up have driven the world to a full-blown pandemic.

As much as our own government’s response to COVID-19 has been flawed, the epidemic itself is yet another piece of evidence that the United States should be in the business of exporting democracy, rule of law, and transparency. Yet in the last decade, America has turned away from that democratizing mission, and the winds on both left and right suggest we may not turn back anytime soon. So we’ll keep getting sick.

Coronavirus is believed to have sprung from the wet markets of Wuhan Province, China. This sort of animal-to-human leap famously brought us SARS, the H1N1 strain of influenza (which caused the deadly 1918 Spanish flu and the 2010 “swine flu” epidemic), and HIV. The first cases in China were in early December, and after Dr. Li Wenliang warned colleagues later that month, he was warned off by Communist security enforcers. Early strains of the virus sequenced were ordered destroyed in early January. Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping ordered containment—of both the virus and information about it—on January 7. Only on January 20 did the Chinese government allow any public disclosure about the deadly outbreak, and precious weeks were lost. Weeks in which the world might have done more to prevent a pandemic, had both the scientific genome sequencing and the dangers been shared.

Unsurprisingly, Xi’s prime concern was not lives at risk, or containment of the virus, but rather the nation’s and his reputation, place in the global supply chain and his grip on power. In this, Xi is much like every other dictator who prioritizes everything above the well-being of his own people, let alone others’.

Iran, too, has been a poster child for criminal mismanagement of the virus, including the now-infamous video of the deputy health minister feverishly wiping his forehead while denying the severity of the outbreak. He was later diagnosed with COVID-19. Iran has ranked third in the world on cases, behind China and South Korea, but experts agree the Islamic Republic is almost certainly lying about the number of infections and deaths. Meanwhile, rumors continue to swirl at the top levels, with mullahs counseling various insane curatives including licking shrines.

In Russia, the numbers affected are suspiciously low (under 100), but that has not stopped the Putin bot army (and the Chinese and Iranian’s) from aggressively selling disinformation, including that the U.S. is weaponizing the virus. Even as Russia joins the dictator bandwagon denying the truth to its own people, it is using the opportunity to sow distrust and division abroad.

When we consider the United States’ failings on this front, it’s fair to argue that Donald Trump has been more Xi and less Abraham Lincoln than desirable. (See, in particular, his insistent tweets that the virus was “contained” in the United States and his reluctance to let in the passengers of the Grand Princess cruise ship because it would hurt the “numbers.”) The president and the CDC were initially slow to face up to the challenge.

But even in this instance, the nature of the American democratic state has served to diffuse Trump’s selfish impulses, with institutions stepping up to fill the void. And as we will likely see, the U.S. will belatedly come to speed, with lower fatality rates that reflect the democracy/dictatorship divide.

Even Italy, which has, like the United States has been too slow to recognize the gravity of the COVID-19 threat, can argue persuasively that had the People’s Republic of China been more forthcoming about virulence and prevalence, so too Italian authorities might have been more mindful as the virus spread silently. Democracies can, as Italy proves so often, be incompetent; but there is no evidence that Italian authorities sought to suppress or hide information from their people or the world.

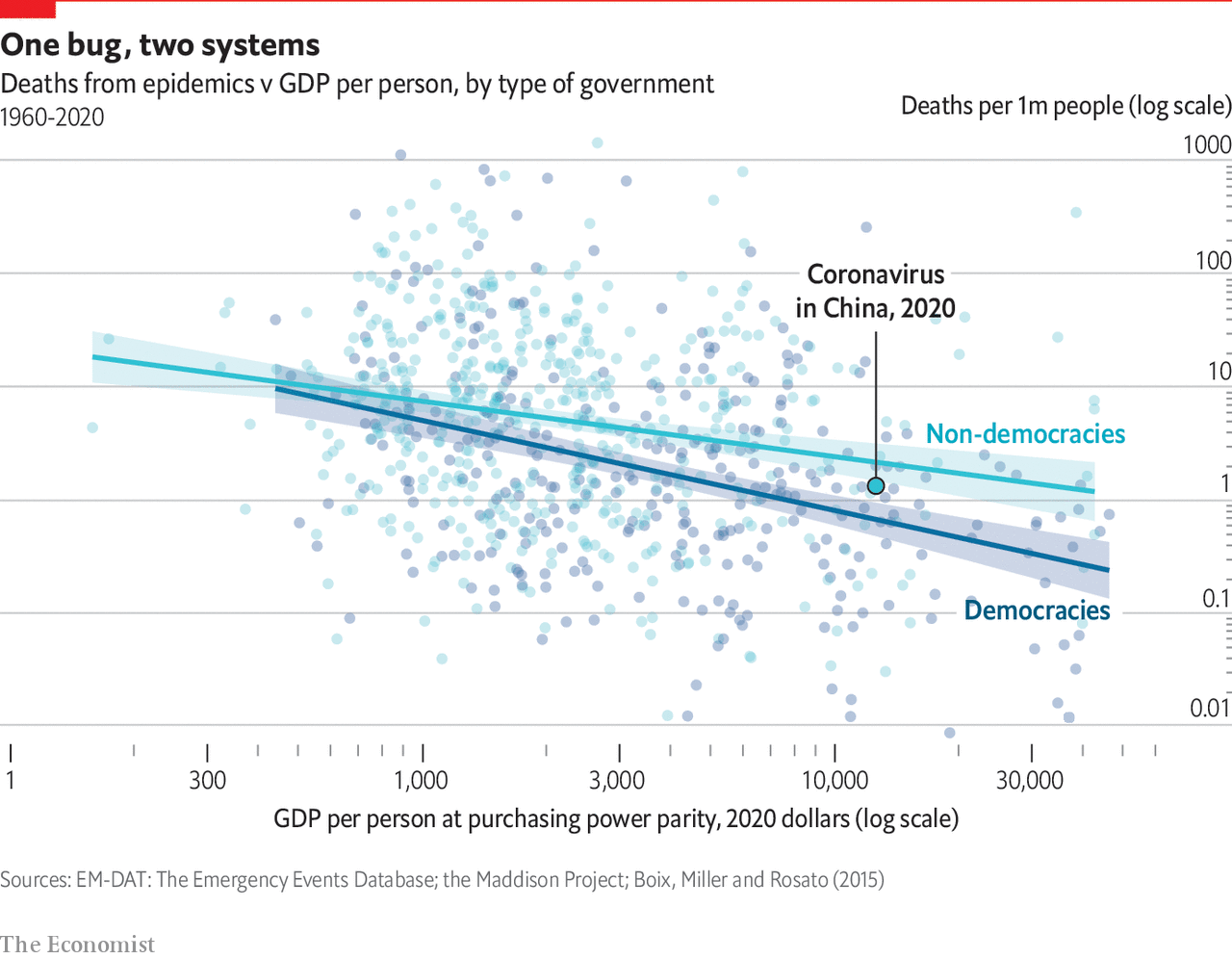

Cultural differences aside, the real difference between the Chinas and Irans and the rest of the world is the nature of communication between the people and their government. To put it bluntly, more people contract disease and more people die in countries without democratic governance. Check out this remarkable Economist chart that lays it out in start terms:

The Economist explains:

Using data from the International Disaster Database, maintained by researchers at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, we analysed all recorded epidemics since 1960, from an outbreak of smallpox in Nepal in 1963 to more recent threats such as Zika and Ebola. The results were highly dispersed but a distinct trend was apparent: for any given level of income, democracies appear to experience lower mortality rates for epidemic diseases than their non-democratic counterparts (see chart). In authoritarian countries with China’s level of income, for example, we found that past epidemics have killed about six people per 1m population. In democracies with similar incomes, they have killed just four per 1m.

At the end of the day, The Economist found what some of us instinctively know: Democracies, despite the lack of diktat, despite the consensus building required, despite the cumbersome decision-making process, are not afraid of the people. Democratic leaders are not afraid of information, and as a result, can judge the efficacy of their efforts, can fine tune and adjust, and can respond to the flow of news in a way that optimizes life saving.

But in a world where three major revisionist powers are dictatorships (China, Russia, Iran), the relationship of those dictatorships to the rest of us starts to matter more. If you’re an isolationist or a libertarian—strains of which have been evident in both this and the last administration—your view is that neither the systems of governance nor the life expectancy of your average Chinese, Russian or Iranian is of much moment to Joe Sixpack. Perhaps, if you’re talking about basic standards of human freedom, that’s right. But if you’re talking about killer viruses, the calculus starts to change. In short, it would have been much better if Xi Jinping were not a lying dictator, but a leader elected by his people and unafraid to combat a deadly pandemic.

What can we do? Both Donald Trump and Barack Obama have downplayed the importance of democracy in American foreign policy. For Obama, it was all about repudiating the Bush administration’s freedom agenda. For Trump, it’s anyone’s guess, but the president has made no secret of his predilection for strongmen. Both presidents reflected their own biases against democracy promotion with requested budget cuts, requests that for the most part Congress ignored. But budgets don’t always drive priorities, and both Obama and Trump have more or less ignored some of the most pressing cases—Russia, Syria, Iran, China—where there have been opportunities to drive meaningful change.

It is fair to say that not all U.S. efforts to promote democracy have borne fruit (Iraq being the favored example of the 21st century); it’s also fair to say that the history of the 20th century suggests such transformations are very possible. At the turn of the 20th century, there were precious few democracies; in 2019, they outnumber autocracies or dictatorships by any measure. Even absent military action, the United States can advance democracy by prioritizing it in foreign policy—for example, by working harder to ensure that there is a democratic alternative to Bashar al-Assad, or Vladimir Putin.

This is not the place to talk about how democracy promotion might be reformed. It is, however, the right place to note that the costs of trafficking with dictatorship are not simply moral. As COVID-19 has made clear, lives will be lost because of the global ripple effect of decisions made by dictators.

Photograph of Xi Jinping by Ju Peng/Xinhua via Getty.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.