Many American conservatives have a soft spot for Viktor Orbán because of his rhetorical and ideological affinity with Donald Trump and Trumpism, as well his uncanny ability to “own” Europe’s liberals. Under his watch, the Hungarian government openly weighed in in favor of Trump’s reelection last year and even flirted with conspiracy theories about supposed voter fraud in the United States.

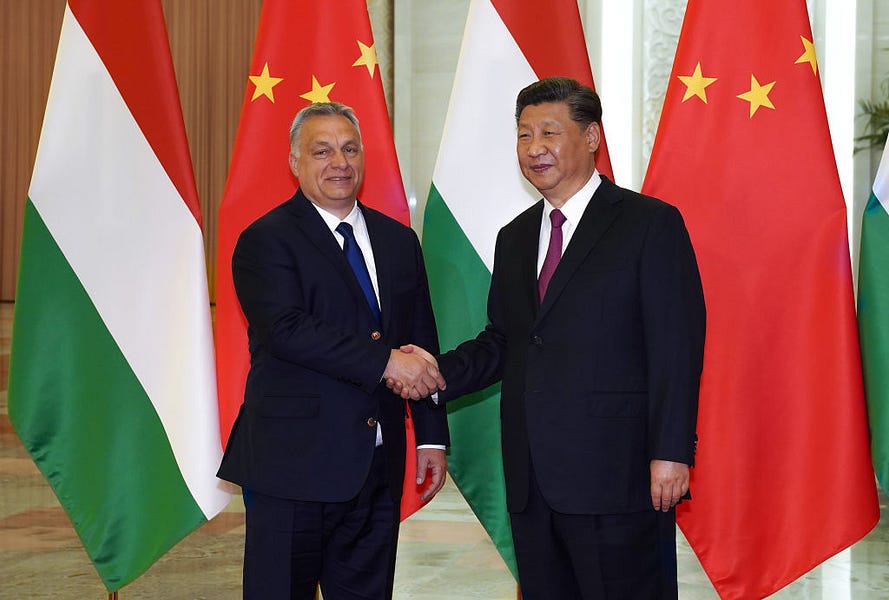

Here’s a paradox. Despite his status as the former president’s best friend in Europe, the Hungarian prime minister has also relentlessly pursued deeper economic and political ties with China, the country Trump himself identified as America’s main geopolitical foe.

The Hungarian government’s firm embrace of Beijing dates back to 2010, when the right-wing populist Fidesz party returned to power after two terms in the opposition. Orbán became prime minister as a result of those elections. He praised the Chinese Communist Party regime in 2011 because it “was not dominated by that Western, liberal idea that fiddling with the books is the way to get the best economic indicators. There, work is the foundation.”

Before concerns over Chinese influence were on anybody’s radar in Washington or Brussels, Hungary hosted a series of high-profile summits with China, struck cooperation agreements, and attracted Chinese investment. In June 2011, Huawei announced it would establish its European logistics center in Hungary. Chinese company also took control of Borsodchem, a major Hungarian chemicals manufacturer, in a $1.66 billion deal.

In 2015, Hungary led the pack as the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Later, Orbán called Hungary a “pillar” of BRI. The Initiative’s most tangible manifestation to date has been the Chinese-funded construction of a new railway connection between Budapest and Belgrade, ostentatiously built to better connect Greek ports bringing in Chinese exports with European markets. Details of the contract, worth $1.9 billion, are classified.

The most recent example of this rapprochement, a decision to build a Hungarian campus of Shanghai’s Fudan University in Budapest, provoked a public blowback. The cost of the project, $1.8 billion, financed largely by a Chinese loan, exceeded the government’s entire budget for higher education in the country. The symbolism was striking, particularly following the expulsion of the George Soros-founded Central European University in 2019—an institution that had put post-communist Hungary on the map as a center of world-class teaching and scholarship in social sciences, and particularly studies of transitions.

On a poll, only 20 percent of respondents supported the Fudan venture. The local council in Budapest showed their true sympathies by renaming the surrounding streets with titles such as “Free Hong Kong Road,” “Dalai Lama Street” and “Uyghur Martyrs’ Road.” Following mass protests in early June, the project was shelved—or, rather, Orbán announced that a referendum would be held on the subject.

This rare example of Orbán backing down in face of public pressure has to do with the looming 2022 election. He faces a real chance of being ousted by an extremely broad coalition ranging from the formerly neofascist right to the progressive left.

But there has long been another problem with Orbán’s frequent large bets placed on deepening Hungary’s relationship with China: For a long time, the partnership did not deliver.

In 2019, China accounted for merely 1.5 percent of Hungary’s exports, or $1.79 billion. Likewise, investment flows ($194 million from China and $426 million from Hong Kong in 2019) were a fraction of the foreign direct investment coming from other Asian economies, such as Japan ($1.5 billion), Korea ($3.3 billion), and Singapore ($557 million). In spite of the pandemic, 2020 was supposed to be different, according to Hungarian officials, with a record number of new investment projects placing China as the largest foreign investor in the country.

Yet, overpromising and failing to deliver is a well-known pattern for Chinese economic outreach in Central Europe, including prominently in the Czech Republic, where the now-defunct CEFC investment group made inroads with prominent political leaders, including President Miloš Zeman. As the economic benefits failed to materialize, Czech critics of China were able to speak out ever more loudly, culminating in an official visit of Speaker of the Senate Miloš Vystrčil to Taiwan.

The scant benefits of Hungary‘s relationship with China to date, in contrast, have not prevented Orbán from acting as the CCP’s most reliable European ally. “It is absolutely no exaggeration to say that relationship between China and Hungary is in its best form,” Foreign Minister Péter Szjjártó said in 2019. “It always has been good, always, but now it is in its best form.” Over the years, Hungary has repeatedly blocked the EU’s initiatives and statements seeking to hold China accountable—in 2016 on the South China Sea, in 2017 on the torture of detained Chinese lawyers, or in 2018 on human rights. While the EU has been able to adopt a sanctions regime responding to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Hungary has repeatedly blocked efforts by the EU to criticize China over the abuses in Hong Kong.

Not only has Orbán lambasted such efforts as “politically inconsequential and frivolous,” but China also caused Hungary to stand up to the Trump administration. The government refused to join the initiative of then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo aimed at dissuading Central and Eastern Europe from using Huawei to build its 5G networks—something that was in Hungary’s “economic and strategic interest,” according to Szjjártó.

In this respect, Orbán played the previous U.S. administration like a fiddle: The two leaders’ shared dislike of the left, immigrants, and the European Union mattered to Trump more than a sharp divergence of opinion on a matter central to U.S. foreign policy.

Under the Biden administration, the Hungarian government is bound to come under much tighter scrutiny. Not only does China remain the focal point of U.S. foreign policy but, unlike during Trump years, the current president is vocal about placing the rule of law, democracy, and human rights at the center of America’s engagement with its allies—something that does not bode well for Orbán’s autocratic practices. Yet just how much leverage Biden’s America has to stop and reverse Hungary’s ongoing Sinicization is an open question, and I am not holding my breath.

Dalibor Rohac is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington DC. Twitter: @DaliborRohac

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.