It was not because it was proposed to establish a new nation, but because it was proposed to establish a nation on new principles, that July 4, 1776, has come to be regarded as one of the greatest days in history.

— President Calvin Coolidge, The Inspiration of the Declaration, delivered in Philadelphia, July 5, 1926, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of America’s founding.

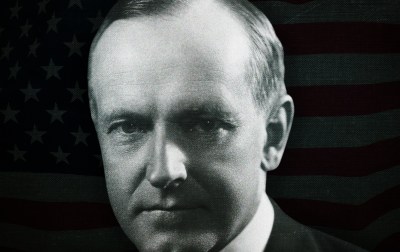

Calvin Coolidge probably couldn’t get elected president these days. Then again, Calvin Coolidge probably couldn’t have gotten elected in 1920, either.

But he could get elected vice president, and, thanks to a combination of corruption and congestive heart failure, that was good enough.

Coolidge, as his definitive biographer Amity Shlaes wrote, “made a religion of thrift and became its prophet.” His personal and political style was that of the pinched Vermonter: dark-suited, deliberate, taciturn, reserved. His policies were made to match: spend less, limit government, wait and see.

That was not the vibe American voters were looking for in 1920. The man they elected that year, Ohio Sen. Warren Harding, was handsome, gregarious, open-handed, and freewheeling. The “not nostrums but normalcy” that Harding was selling in his campaign that year wasn’t a constrained vision, but one that let the good times roll after eight years of progressivism, war powers, and pandemic.

Your high school history teacher probably told you that Harding was a Babbitt-like man: a dope and an empty suit who craved conventionality and mouthed the right-minded pieties of his day. The truth is that Harding was smart, wildly ambitious, and a real operator, with, as history would reveal, a personal life to match. He was, as the politically fashionable would say today, a man who could “meet the moment” of 1920.

Not Silent Cal.

While Harding was doing a hedonistic Horatio Alger in Ohio, Coolidge was building a career like he was stacking stones for a Vermont farm wall. He settled in Northampton, Massachusetts, near his alma mater, Amherst College. He apprenticed himself to two well-established local lawyers and then set up a practice of his own doing commercial law, met and courted his wife, Grace, a teacher at the town’s school for the deaf.

After 12 years stacking stones—mayor, then state senator, then state Senate president, then lieutenant governor—Coolidge made it to the top of Massachusetts politics and was elected governor. After just a year in office, he was certainly not angling to be on the Republican ticket, top or bottom, in 1920. But there were plenty of men who were trying hard, including Sen. Harding and his campaign manager, a statehouse operator and would-be political boss, Harry Daugherty.

A divided progressive majority at the Chicago convention put Daugherty in a position to put Harding forward as the compromise choice. And on the 10th ballot, after lots of wheedling in the parlors of Chicago’s Blackstone hotel, Harding was the man. The deal held that Harding would be paired with a progressive, the radical California senator and former governor, Hiram Johnson—Harding for electability and the squishy center with Johnson as a sop for the true believers.

Well satisfied, Daugherty and the bosses left early on the next night of the convention, leaving it to underlings to manage the Johnson nomination.

But Coolidge had become a favorite in the conservative minority for his famous breaking of the Boston police strike the previous fall when he sent in the state militia. His admirers had published a collection of his speeches in a slim volume called Have Faith in Massachusetts that became a hot number at the convention.

It was an old-fashioned stampede—a popular revolt by the delegates. But unlike the one that had made William Jennings Bryan the Democratic nominee in 1896 after his Cross of Gold speech, Coolidge wasn’t even there. The Massachusetts governor, without any effort of his own, had become the vice presidential nominee. The Ohio Gang was displeased, but Coolidge, they figured, wouldn’t be much of a liability.

They were right. Harding and Coolidge romped to the largest-ever popular vote victory since the founding era: more than 26 points, winning every state outside of the former Confederacy and Kentucky. The nation was ready to forget about Woodrow Wilson’s nostrums, wartime privation, and somberness.

You know what happened next: The Roaring ’20s really got roaring. Pent up demand, technological advancements, and the lifting of wartime controls sent the economy soaring. The Harding administration was stacked with big name, big money Republicans: Charles Evans Hughes at the State Department, Andrew Mellon at Treasury, and Herbert Hoover at Commerce. But Harding saved the worst man for the most important job: Daugherty, a statehouse fixer and sometime bag man, would be his attorney general.

And as for Coolidge, everybody promptly forgot about that old stiff. The big names were off to conquer the world and build their own careers and had no use for the decidedly provincial veep. Daugherty and the Ohio Gang knew that Coolidge was dangerously ethical and promptly set him in the corner like a potted plant.

And everything was just chugging along for the first two years, until the spring of 1922 when the Wall Street Journal blew the lid off the story of how Harding’s supporters in the oil industry had gotten sweetheart deals on leases on federal petroleum reserve land, including the rich Teapot Dome in Wyoming, and officials were rewarded with “loans.”

What followed was a political drama so sordid that no novelist would dare try to sell it. Daugherty and Harding were settled on a fall guy to take the rap, but the fall guy killed himself in Daugherty’s suite at the Wardman Park Hotel rather than be fed to the wolves.

That happened right before Harding was supposed to go on a tour of Alaska and the West. He was going to get out of Washington and away from the scandal, refurbish his image, and make a soft launch for his 1924 reelection campaign. The suicide hung a cloud over the trip.

Bon voyage, Mr. President.

Harding made it to Alaska and, three weeks later, was heading south. But he only made it as far as San Francisco, where he collapsed and was taken to the Palace Hotel. Five days later, Harding was dead.

Now the potted plant was the president of the United States.

The story of Coolidge’s inauguration is as much a part of the Coolidgian lore as his one-liners—supposedly telling the party guest that bet her friend she could get him to say more than two words: “You lose.” But Coolidge really did receive word of Harding’s death at almost midnight by messenger at the family’s homestead in Plymouth Notch, Vermont. And Coolidge’s father, a justice of the peace, really did administer the oath of office to his son by the light of a kerosene lamp at a little bit before 3 a.m. on August 3, 1923.

Which is all a very long way of saying that when Coolidge became president, things were not going the right way. The rustic, old-fashioned, penny pincher who was so thrifty that he never even owned his own home was not the man America was looking for to manage a period of booming growth, big social changes, and a federal government that, even after wartime spending had ended, was still twice the size it had been before the war.

But, of course, he was the perfect person.

Coolidge set right to work cleaning house in the administration and cutting spending. He devoted time every day to go through the budget, line by line, looking for waste and abuse. He executed the public duties of office, but did little in the way of “messaging.” He was always careful, cautious, and earnest, and voters loved it.

“Not one word of what Coolidge said is out of place for us Americans nearly a century later. We worship the power and wealth of our nation but are much inclined to forget that those things are a byproduct of the ideas of the founding, not the purpose of the nation.”

Maybe not the progressives, though. So successful were Coolidge and the Republicans that the Democrats set to imitation, picking a sobersided moderate from West Virginia, John Davis, to carry their new message of restrained government, lower taxes, and less regulation. But Coolidge was so good at being president that just 15 months after he inherited the job, he won in a landslide.

America, therefore, was feeling very good about itself and very fond of its modest, diligent president as preparations got underway in 1925 for the next year’s celebration of the 150th anniversary of the nation’s founding.

The action would naturally center on Independence Hall in Philadelphia, as it had for the centennial 50 years before. The city would again host the World’s Fair, the Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition, and would again erect a massive temporary city to host millions of visitors from across the country and around the world. An 80-foot replica of the Liberty Bell adorned with 26,000 light bulbs, a new stadium (which would later be named for John F. Kennedy and stand until the 1990s), and a grand new bridge across the Delaware River were all built for the occasion.

Fifty years prior, the nation had tried to project optimism. After the Civil War and during a period of rapid western expansion, Americans wanted to tell the world that we were going to become a great and powerful nation. In 1926, that matter was no longer in doubt. The American colossus was ready to receive its laurels. And they poured in. Benito Mussolini, for one, gave a massive replica of Bernini's Fountain of the Sea Horses that still stands in Fairmount Park to this day.

Nicknamed “the Sesqui,” the exposition drew some 10 million visitors: a grand celebration for a grand nation. And it was all supposed to lead up to the capstone moment: a speech by the president. Yet again, quiet Coolidge seemed out of step with the moment.

On the same day that America was celebrating its 150th birthday, Coolidge was celebrating his 54th, the only president to be born on the Fourth of July. He might have gone to Philadelphia that day and put himself at the center of everything: a boastful and bombastic speech preceded by a parade and followed by a massive fireworks display. Who could have begrudged him a little triumphalism?

But his birthday and Independence Day fell on a Sunday that year, so the Calvinist Coolidge took his wife and son to worship at the First Congregational Church in Washington and then had a quiet supper at home. Philadelphia could wait for Monday.

America’s civic life is sewn together by words. The longest and best thread of those words started in Philadelphia in 1776 with the American creed that laid out the idea of the new nation: “All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Beginning a war of rebellion, the signatories said, was worth the price in service of those ideals.

Eighty-seven years later, President Abraham Lincoln declared a “new birth of freedom” at Gettysburg, pulling the thread and making another stitch, declaring that the purpose of an awful war was to see that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

What would Coolidge, most famous still for not having much to say, add to all that?

Coolidge may not have been interested in a triumph for himself or even for the nation, but he did go to Philadelphia to declare victory. Thomas Jefferson and Lincoln had been speaking in the future tense when they described what the idea of America was to be. No one in 1776 or 1863 would have believed that those bold claims were guaranteed to take solid form. But in 1926, Coolidge was delivering a statement of fact.

The heart of the speech bears examining at length:

About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful. It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning can not be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final.

Around the world and in America were many loud voices like those of the fountain-giving Mussolini or former Presidents Wilson and Teddy Roosevelt. They promised modern, scientific governance for a modern, scientific age. Slow, stodgy republican self-government was not equal to the task of a fast-paced, dynamic world. But Coolidge turned that around.

No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction can not lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.

Coolidge held that progressivism, socialism, nationalism, communism—all of the -isms so popular in his day—were not modern innovations but rebranded forms of the systems that had for most of human history held people under their heels.

We live in an age of science and of abounding accumulation of material things. These did not create our Declaration. Our Declaration created them. The things of the spirit come first. Unless we cling to that, all our material prosperity, overwhelming though it may appear, will turn to a barren sceptre in our grasp. If we are to maintain the great heritage which has been bequeathed to us, we must be like-minded as the fathers who created it. We must not sink into a pagan materialism.

Not one word of what Coolidge said is out of place for us Americans nearly a century later. We worship the power and wealth of our nation but are much inclined to forget that those things are a byproduct of the ideas of the founding, not the purpose of the nation. We grow weary of dysfunctional government that is slow to respond to the pressing issues of modern life. We demand a system that gives us more of what we want and does so quickly.

But Coolidge called for nothing less than another Great Awakening in which the spiritual gifts that informed the age of the Revolution would be rediscovered

We must cultivate the reverence which they had for the things that are holy. We must follow the spiritual and moral leadership which they showed. We must keep replenished, that they may glow with a more compelling flame, the altar fires before which they worshipped.

Not a popular sentiment for his time or for ours, but a necessary one. And that was Coolidge. Not the president that America would have wanted, but very much the one that it needed. May we be blessed with one just like him as Americans contemplate our nation at 250.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.