In Washington, at 1625 K Street Northwest, there stands an unremarkable office building: 12 floors, putty-colored, smallish windows.

Built in 1941, the Commonwealth Building has been periodically updated over the years to its current state, a nondescript scale on the long snakeskin of K Street lobby and law firms.

You could walk past the frame shop, the loud silk shirts in the crowded window of the men’s store, and the supplement ads of the GNC on the ground floor 100 times on your way to Connecticut Avenue or the Capitol Hilton and never have the building register in your mind.

But on this day 100 years ago, 1625 K Street NW was very much on the minds not only of Washingtonians, but of all Americans paying attention to the scandals that were burning through the administration of President Warren Harding.

Back then, it was an equally unremarkable structure when compared to the grander mansions of the neighborhood: two stories of stone with an attic and a little cupola on top. The only distinctive thing about it was the green paint on the wooden trim. That’s why they called it “the little green house on K Street.”

In the spring of the year before, the Wall Street Journal had dropped a blockbuster story about how oil executives, some of the same ones who had aggressively backed and lavishly funded Harding’s nomination and election, had gotten sweetheart deals on leases in federal petroleum reserves. One in particular, Wyoming’s Teapot Dome, was particularly desirable for its estimated reservoir of 150 million barrels.

Interior Secretary Albert Fall had granted the leases at favorable terms without public bids. It would be years before it was revealed the extent of Fall’s corruption in the case—including a $1 million “loan” (more than $17 million today) from oilman Harry Sinclair—but the secrecy of the deal and generous terms were enough to trigger outrage not just among Sinclair’s competitors but among the progressive members in both parties.

As the scandal simmered, it brought new scrutiny to the so-called “Ohio Gang” in Harding’s administration, and its ringleader, Harry Daugherty. Daugherty had been the maestro behind the genial, handsome, but weak-willed Harding’s surprise victory at the 1920 Republican convention. When Harding won the presidency, he named Daugherty his attorney general. The abuses that followed putting a party boss in charge of the Justice Department were as egregious as they were predictable.

Harding had stood by Fall when the oil scandal broke, and in a testament to his poor judgment and loyalty to his cronies, had offered to put Fall, who would eventually be sent to prison for his crimes, on the Supreme Court when he notified the president of his plans to resign.

With Fall gone, the focus shifted to Daugherty’s assistant and bag man, Jess Smith. Smith held the lease on that little green house on K Street, which served as Daugherty’s citadel of corruption, political and personal. It was Harding’s refuge from the White House, and provided an atmosphere that was, in the words of one historian, “part brothel, part speakeasy.”

As the press zeroed in on Smith, even Harding was ready to cut his losses. And Daugherty, no doubt seeing the personal benefits of pinning the blame on his aide and then banishing Smith, agreed.

The president was scheduled to take a historic westward trip in the summer of 1923, dubbed the “voyage of understanding.” The president and first lady would travel by train across the continent and then steam north to Alaska where he would become the first sitting president to visit the territory. Then he was to sail down the West Coast, all the way through the Panama Canal, and then back home to Washington by the end of August.

The three-month sojourn would offer Harding the chance to boost his support out West ahead of the 1924 campaign, but also get the president out of Washington, which was important for a couple of reasons. One, his health, weakened by stress and his heavy drinking and smoking, might benefit from clean air and cleaner living. Two, it would physically and figuratively distance him from the unfolding scandals of his administration.

Harding told Daugherty before he left that Smith had to go. But after the attorney general sent him packing, that night, alone in the attorney general’s suite at the Wardman Park Hotel, Smith shot himself in the head. It was front-page news and, though ruled a suicide, prompted conspiracy theories that Smith had been murdered to keep him from snitching on the Ohio Gang. The “return to normalcy” that Harding had promised in 1920 was lost in the fog of self-dealing, chaos, and intrigue.

It was under that cloud that Harding set out for his trip. The journey was uneventful, and the president was drawing big crowds even as the scandals continued to play out on the East Coast. By the time they set off for Alaska on July 5, hopes were high that Harding had been physically and politically rejuvenated.

By the end of three weeks in Alaska, though, the president was suffering from cramps and shortness of breath, and had lost his stamina. By the time the party made it to San Francisco on July 29, Harding struggled to walk and was rushed to the Palace Hotel, where a team of doctors could examine him. They found he had a weak heart and pneumonia, and ordered indefinite bed rest.

That was the story of American politics on this day 100 years ago. The sitting president, mired in scandal, was holed up in a San Francisco hotel room, too weak to continue the trip that was supposed to be his comeback tour. From the little green house on K Street to the Palace Hotel, the outlook was grim.

The next day, Harding was feeling better and doctors felt encouraged. The president was sitting up and chatting with his wife. But you know what happened next: Harding died. There were those who said it was a poisoning, and the conspiracy theorists took the first lady’s refusal of an autopsy as very suspicious. Doctors didn’t know about cardiac arrest as they do today, and they thought maybe it was a cerebral hemorrhage. The uncertainty led only to more speculation.

But through this little crack in the door that history had opened, a most unlikely hero squeezed in.

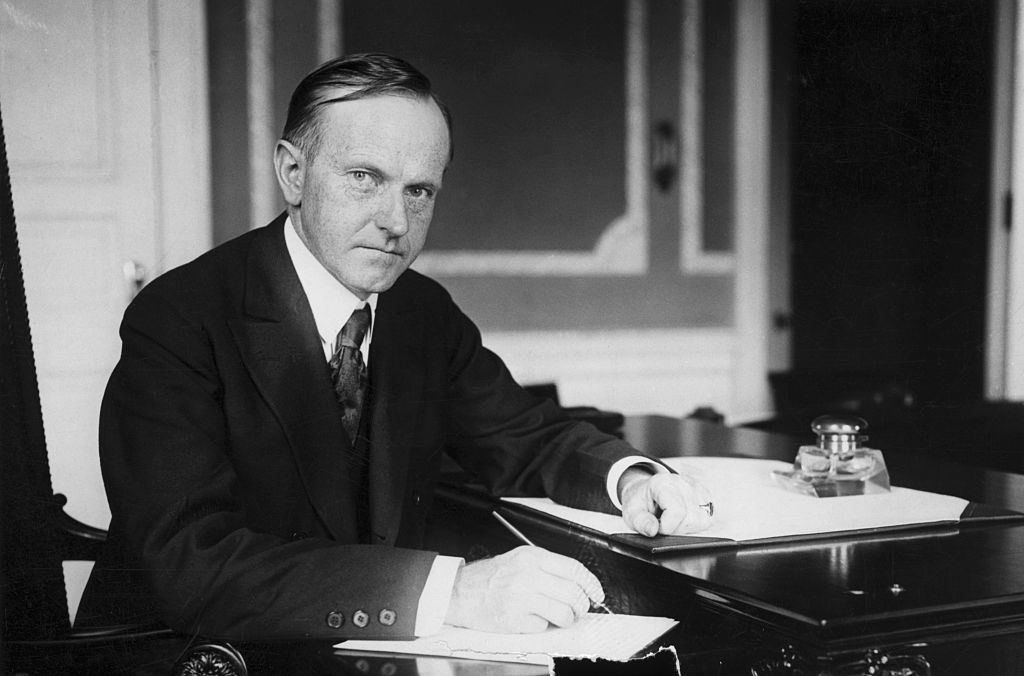

Vice President Calvin Coolidge received word of Harding’s death at almost midnight by messenger at the Coolidge family’s homestead in Plymouth Notch, Vermont. You know that story, too: Coolidge’s father, a justice of the peace, administered the oath of office to his son by the light of a kerosene lamp at a little bit before 3 a.m. on August 3, 1923.

Coolidge was Harding’s opposite in nearly every way. Where Harding was weak-willed, Coolidge was tough. Where Harding was led around by his friends, Coolidge kept his own counsel. Where Harding was dissolute, Coolidge was the model of flinty New England rectitude. Where Harding had been for high living and found wealth as a publisher, Coolidge lived humbly. Where Harding allowed chaos, Coolidge was abnormally, well … normal.

Harding and his gang had known to keep Coolidge far away from the shady dealings and louche living on K Street. The former Massachusetts governor, who had won acclaim for his steely response to the Boston police strike of 1919, had been forced onto the ticket against the party bosses’ wishes by popular demand at the 1920 convention, after a delegate had circulated a bound collection of Silent Cal’s speeches. He was treated with deference by the gang, but was viewed suspiciously and kept very much out of the loop.

You already know the rest of that story, too.

Coolidge, quietly, deliberately, carefully cleaned up the government. His modesty and decency proved to be the balm that the nation needed at a time of political and social unrest. His good sense and good character kept his administration out of trouble, and finally provided the stability the nation had sought since the upheavals of the Great War. He fulfilled the Founders’ vision of executive leadership at a time when institutions were breaking down.

No political operator could have drawn up the plan for Coolidge’s rise or his success as president. But he was most certainly the man for the moment. If you are inclined to believe in providence, his story ought to give you goosebumps.

“There is only one form of political strategy in which I have any confidence,” Coolidge wrote in his autobiography, “and that is to try to do the right thing and sometimes to succeed.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.