It’s one of the strange ironies of American politics. Few things are as politically polarizing as foreign policy, and yet it’s on foreign policy where the differences between the parties are often narrowest. Indeed, viewed from abroad, our allies and adversaries often think that the biggest problem with any new administration is the continuity of U.S. policies, not the change in direction.

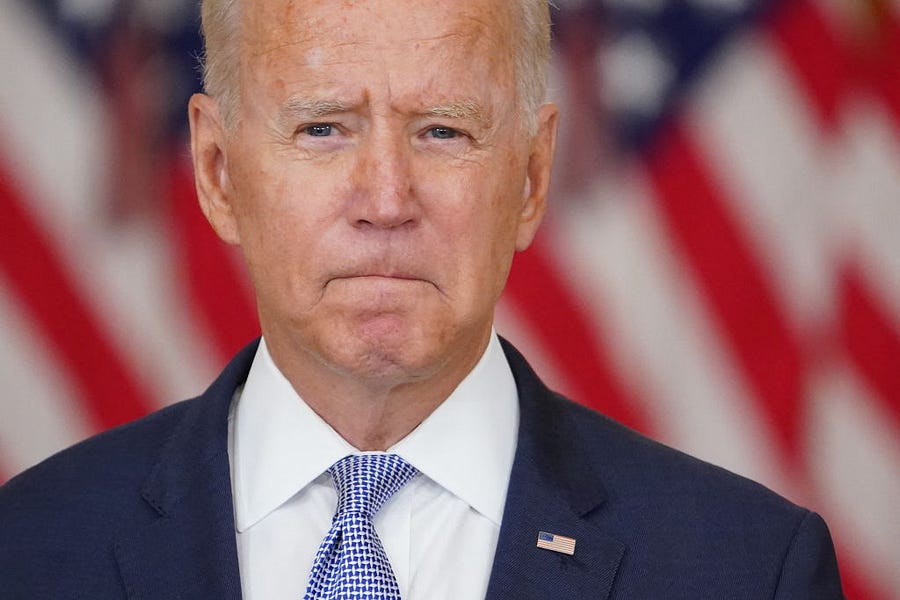

Consider two opinion articles on Biden’s foreign policy published late last week. Fareed Zakaria, writing in the Washington Post, asked, “Is Biden normalizing Trump’s foreign policy?” Michael Rubin, writing in the Washington Examiner, asked, “Is Biden’s foreign policy really different from that of Bernie Sanders?”

Both foreign policy experts make a good case. Zakaria notes that, despite his campaign rhetoric, Biden is largely retaining Trump’s trade policies. A Canadian politician, Zakaria points out, even gripes that Biden’s “Buy America” provisions are more protectionist than Trump’s. The Biden campaign had pummeled Trump’s decision to pull out of the Iran deal, but the Biden administration hasn’t restored the deal, arguing instead to “lengthen and strengthen” it. Biden has kept Trump’s Cuba policy and has even tightened sanctions.

Rubin sees Cuba as one of the only stark differences between Biden and Sanders on foreign policy (the other being Israel). The most obvious similarity is on trade. Sanders, like Trump, hated the Trans-Pacific Partnership championed by Barack Obama. As vice president, Biden praised it, but now he’s following the Sanders-Trump consensus.

Evidence of continuity or consensus doesn’t end there. On Afghanistan, though Republicans and many Democrats rightly criticize Biden’s shambolic withdrawal, the underlying policy is consistent with the stated goals of not just Trump but Obama too.

Last week, the Biden administration announced a defense and trade agreement with the United Kingdom and Australia, dubbed AUKUS, that has enraged the European Union, particularly France, in no small part because it will cost them billions in submarine sales to Australia. This trilateral security alliance is a smart move. But it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see that it could have been hatched in the Trump administration.

And on Friday, the Biden administration appealed a federal court ruling that suspended a Trump administration policy of using a public health law, known as Title 42, to expel migrants seeking asylum.

Now, I don’t think Biden starts from the same ideological assumptions of Trump or Sanders. The fact is that ideological commitments and rhetorical broadsides tend to obscure the reality that presidents do not have the free hand in foreign policy everyone pretends they do.

For instance, Obama saw the world very differently from George W. Bush, but he held on to many of the Bush administration’s most controversial national security measures, including a heavy reliance on targeted drone strikes and keeping Guantanamo Bay open. He even launched a “war of choice” in pursuit of regime change in Libya.

Jimmy Carter came into office seeking deep defense cuts and boasting that he lacked the “inordinate fear of communism” that justified Cold War hawkishness. He ended his presidency asking Congress for a big increase in defense spending to “contain Soviet aggression.”

Former British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan purportedly was once asked what he thought the greatest challenge to his administration might be. “Events, dear boy, events,” he allegedly replied.

The nice thing about the word “events” is that it doesn’t draw a distinction between domestic and foreign affairs or between left and right. It’s likely that Biden doesn’t like turning away asylum seekers at our border any more than Obama did. But events at the border drive a political and policy necessity to stanch the flow, and there is no “left-wing” way to do that.

The downside of the word “events” is that it excludes the role of interests and inertia. It may have been easy for Biden to rejoin the Paris climate accord—just as it was easy for Trump to leave it—but that’s because it is a largely symbolic and toothless agreement. Rejoining TPP—which America should do—would require crossing special interests Biden relies upon, risking alienating voters Democrats need and turning around a vast bureaucratic enterprise.

This can be frustrating, but it’s also somewhat reassuring. Robert Gates, Obama’s Republican secretary of defense, famously said that Joe Biden was wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the last four decades. I concur. Trump, of course, had a deep reservoir of bad opinions as well, from wanting to confiscate Middle Eastern oil to defenestrating NATO to banning all Muslims from the U.S.

I understand why you’d want a president you agree with to have a free hand on foreign policy, but shackles have their upside.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.