Last week, the Supreme Court ended one its most hotly contested terms in decades despite issuing the fewest signed opinions in 158 years. Headlines included abortion, LGBTQ rights, immigration, gun rights, criminal justice, religious liberty, and the powers of the presidency. (For a rundown of all the major cases, check out our pre-term guide to the top 10 cases and Advisory Opinions podcast.)

But at a time when political polarization is reaching new heights and both political parties want to energize their voters about the dangers of the other, the most frequent commentary often involved which side was losing more ground in these legal battles. Democrats discussed packing the court after a Biden victory. Republicans debated whether the project of legal conservatism should be abandoned altogether.

If a person can be judged by the enemies he makes, it would be fair to wonder after the October Term 2019 (OT19) whether the Supreme Court has any friends left. But one justice seemed to find himself with friends whichever way he looked.

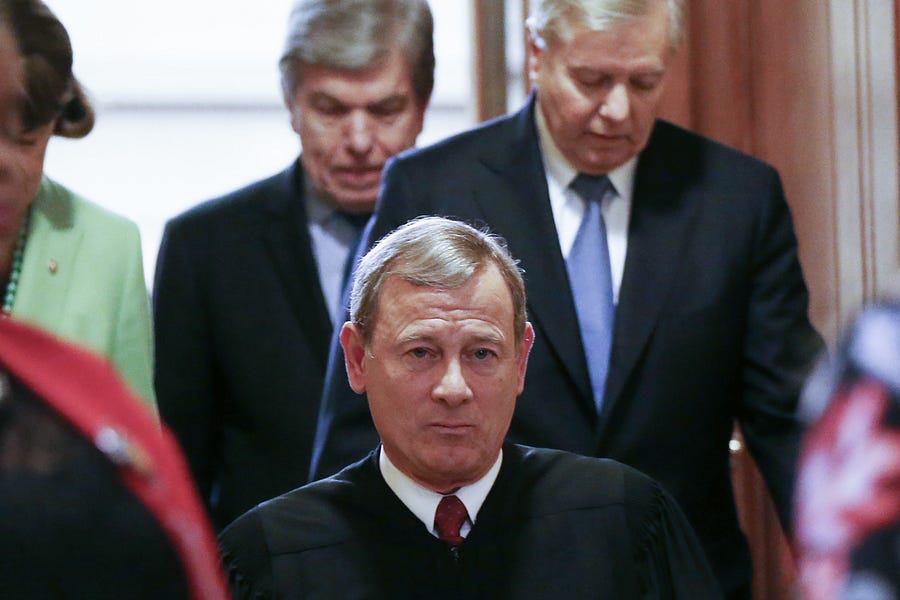

As Chris Walker, law professor at The Ohio State University, told The Dispatch, “this has been such an unusual and important term at the Supreme Court, and Chief Justice Roberts has been at the center of it.”

In the wake of Justice Kennedy’s retirement as the swing vote on the court, Chief Justice Roberts found himself in the majority 97 percent of the time this term.

The swing vote on the court is always a powerful position, but this is the first time since the 1930s that that role has reliably been held by the chief justice. When in the majority, the chief justice has the power to decide which justice will write an opinion—including assigning a case to himself. This means that the chief not only decides the outcome of a case when he is the fifth vote, but also has enormous influence over the contours and implications of these precedents as they continue to shape law down the road.

Not surprisingly, now both sides want to know: Is the new Roberts court conservative or liberal?

Below are the best arguments for each side about who “won” this term at the court.

The Case for a Conservative Victory

The legal conservative movement has been defined by an assertion from Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v Madison. In fact, every meeting of the Harvard Federalist Society starts with a recitation of this mantra: It is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be.

Legal conservatism, therefore, is supposed to be about process and not outcome, and its success at the Supreme Court could be judged by whether the Court looked to the original public meaning of the Constitution and whether the text of statutes drove the decisions more than the legal history.

Under that analysis, Bostock, which held that sexual orientation and gender identity are included in Title VII’s prohibition against sex discrimination, is a clear win. The majority opinion written by Justice Gorsuch claimed the mantle of textualism, the dissent by Justice Alito argued that originalism ought to win the day, and the other dissent by Kavanaugh argued that a better form of textualism existed. Regardless of outcome, a court that is only arguing over which method of conservative interpretation to apply would surely be a victory in process.

But while that may be the case for the Federalist Society, the political conservative movement in the United States is very much concerned with outcome. Bostock’s outcome may not have been a win for social conservatives, but the court’s opinions on religious liberty were numerous and all in one direction. As David French put it so succinctly, “At SCOTUS, people of faith just keep winning.”

The court ruled that religiously affiliated employers have broad hiring and firing discretion outside of traditional discrimination laws, expanding the so-called ministerial exception. It also reinstated a scholarship program in Montana that had excluded religious schools. And then there’s the Little Sisters of the Poor, whose case isn’t over yet but who looked poised for a victory over the government’s contraception mandate, which they argued violated their religious beliefs. And the court agreed to hear a case next term about whether Philadelphia can end its contract with a Catholic adoption agency because it refused to refer LGBTQ couples for adoption.

Bostock also contained a number of potential Easter eggs for conservatives down the road. The Gorsuch opinion was joined by the four Democrat-appointed justices in interpreting Title VII only by its text. As Cass Sunstein pointed out almost immediately, the court’s affirmative action jurisprudence decidedly ignores the text. “In 1979, the Supreme Court ruled that notwithstanding its text, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 permits affirmative action,” he noted, adding that “The court referred to a ‘familiar rule that a thing may be within the letter of the statute and yet not within the statute, because not within its spirit nor within the intention of its makers.’” This does not bode well for the cases currently percolating in higher education around the country, including one against Harvard, which claims its admissions process discriminates against Asian American students.

And even the losses for conservatives may be long term wins. Ian Millhiser at Vox argued that on abortion, immigration, and gun rights, the losses for conservatives were minimal and hardly mortal wounds.

In June Medical, the court struck down Louisiana abortion restrictions that were nearly identical to the same restrictions the court struck down just a few years earlier in Texas. The only thing that had changed was the makeup of the court, with the addition of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. And while those two justices would have voted to uphold the restrictions, conservatives lost the chief, who wrote that he was unwilling to disturb the court’s earlier precedent in which he himself had dissented. “Roberts remains likely to uphold significant restrictions on abortion in the future,” Millhiser put it, “he’s just not willing to uphold the exact same law that the Court struck down a few years earlier.”

On immigration, the court in effect rescinded the Trump administration’s recision of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program on an administrative technicality. The administration is free to try again and appears to have at least five votes if it follows the court’s advice on how to do it legally this time around. And it was not at all clear that the court would uphold a Biden administration’s attempt to reinstate the program, which a lower court has found was unlawful to begin with.

The Case for Liberals

Then again, there must be some reason conservative Sen. Josh Hawley said on the floor of the Senate that the legal conservative movement was dead.

As Hawley said in the context of the Bostock decision, “if we’ve been fighting for originalism and textualism and this is the result of that, then I have to say it turns out we haven’t been fighting for very much or maybe we’ve been fighting for quite a lot but it’s been exactly the opposite of what we thought we were fighting for.” Perhaps so.

In a speech at Harvard a few years ago, Justice Kagan famously said “we are all textualists now.” And while that may have been the stated goal of the Federalist Society at some point, Bostock was hardly the outcome they had in mind. Time and again, Justice Kagan in particular has shown a knack for using conservative interpretative methods like textualism while reaching progressive outcomes. At the Bostock oral argument, it was Kagan who said “This is the usual kind of way in which we interpret statutes now. We look to laws … We don’t look to desires.”

And of course, there are the outcomes, too. Bostock will almost certainly turn out to be the most impactful decision of the term, and on its face, it was unquestionably a win for progressive civil rights advocates. The court dismissed a gun rights case that sought to expand the reach of Heller and McDonald and refused to take any of the pending gun cases next term.

The Trump financial cases may not have have resulted in an immediate release of the president’s tax returns, but it looks very likely that the Manhattan district attorney will win when the case goes back to the district court and that his grand jury will be able to review some portion of the subpoenaed financial records—even if it is after the election.

And speaking of the election, the court’s decision in Little Sisters may have been a theoretical win for the Trump administration’s contraception mandate exemption, but it is also clear that a Biden administration would be able to repeal the exemption before the Little Sisters even win their case outright.

As someone once said, everyone is entitled to their decade in court and liberals may well be able to run out the clock on a one-term Trump presidency.

Lastly, the court’s “severability doctrine” came into sharper focus, and it inevitably will help liberals save legislative victories. This term the court found that the limits placed on the president’s ability to remove the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau violated the Constitution. But they simply removed (or severed) that portion of the law and rejected any arguments that the entire CFPB had to go or the entire Dodd-Frank Act, which created it.

This bodes well for the fall, when the court will hear yet another challenge to the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate. The conservative advocates are arguing that the individual mandate is so central to the functioning of the law that if the mandate is no longer a tax (because Congress zeroed out the tax penalty in 2017) the entire law has to go. The court’s reasoning in the CFPB case and a case it decided on robocalls may well herald good news for the continued viability of the ACA.

Taken as a whole, neither side can be said to have gotten all they wanted from the court. Conservatives saw their first full term with two Trump appointees and still lost, but liberals’ worst fears of a 5-4 steamroller didn’t come to fruition either.

Maybe there is a simpler way to understand this term. Institutions, after all, have a way of protecting themselves in times of political turbulence. And when looked at from that perspective, the court is no exception.

“The suggestion that Roberts votes primarily as Chief Justice strikes me as quite plausible,” Walker told The Dispatch. “In other words, he seems to care first and foremost about preserving the institutional capital of the court and second about saying what the law is … that can be a precarious strategy, to be sure,” he added, “sacrificing the rule of law (at least on the margins) to appear above politics might well backfire, at least in the court of public opinion.”

The court was not intended to be a majoritarian institution, but unlike Congress with its power of the purse or the executive branch with its military, the third branch is only as powerful as those who accept its authority. This is no accident. Alexander Hamilton described the court’s power in Federalist 78: “It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment.” This turned out to be more than a philosophical point after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokees in 1832. President Jackson quipped, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.” He then ignored the ruling and sent federal troops to remove the Indians from their land, culminating in the Trail of Tears.

Election years tend to draw special attention to the court from partisans on both sides who seek to use it as a political football. But on some of the most hot button issues, the court has favored the status quo in recent election years. In 2012, Justice Roberts wrote the majority’s 5-4 opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act. In 2016, a 5-3 majority of the court restated the right to abortion under Roe and Casey.

So where does the court stand with the American public in this election year? According to Gallup, the Supreme Court’s approval rating is the highest it’s been in more than a decade.

Perhaps that’s because the public likes what it’s been seeing. “According to a recent survey by a group of researchers at Stanford, Harvard and the University of Texas, Austin, which asked Americans about central issues facing the court,” Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux at FiveThirtyEight noted, “the justices’ rulings were in line with public opinion in 8 out of 10 major cases.”

In the one potential exception to that public approval, Americans believed that Trump should not be able to block access to his financial records.

Of course, sometimes procrastination is the better part of valor for a court that wants to avoid getting drawn into electoral battles. On the president’s financial records, the court punted back to the lower courts to make a final decision on that question—one that almost certainly won’t be resolved until after the election. And just this week, the court announced which cases it will hear in October. Notably absent was the latest challenge to the Affordable Care Act. The earliest it can now be heard is November 2—the day before the election.

But there’s one thing Supreme Court watchers seem to agree on. “This term, in my mind, solidifies a new era of the Supreme Court as the Roberts Court,” Walker pronounced, “Roberts is the new decider and driver of the court’s future.”

Photograph by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.