Last month, Microsoft announced an advance that could be an important step forward in the long road to building a quantum computer—if true.

A Microsoft research team claims to have built “the world’s first quantum processor powered by topological qubits,” and that it is on track to build a prototype of a scalable quantum computer “in years, not decades.” If that weren’t enough, the company also said it had created in the process “a new state of matter”: a topoconductor. This was just days after Microsoft was chosen, along with quantum computing company PsiQuantum, by the U.S. government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop under-explored approaches to quantum computing, a field that marries traditional computer science, theoretical physics, and mathematics.

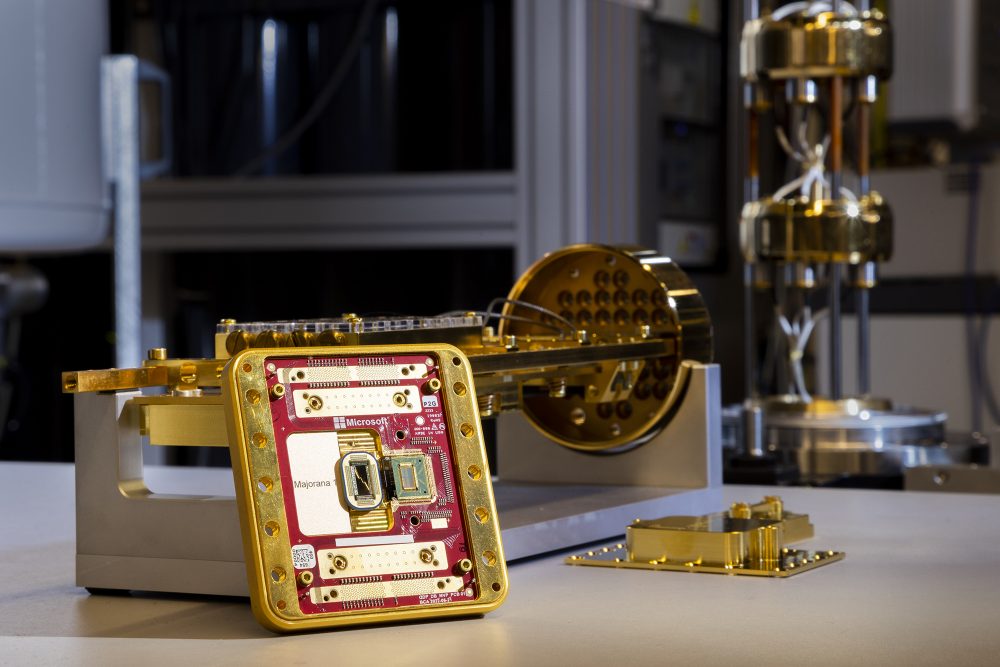

The Microsoft chip—Majorana 1, named after the Italian physicist on whose theories the chip was based—is just the latest in a series of attempts by IBM, Google, Nokia Bell Labs, and others to build the basic mechanism that will run quantum computers. It’s a massively difficult undertaking because quantum computing uses the principles of quantum mechanics, calling for delicate engineering at the level of subatomic particles.

There’s a huge upside to developing computers that go beyond the limitations of today’s classical computers. The operating core of computers hasn’t changed since the explosion of computing began in the late 1940s: Computer chips still store, manipulate, and work according to our instructions using bits—the 0/1 binary logic of all computers. Today’s machines are “just millions of times faster with millions of times more memory,” says Scott Aaronson, professor of theoretical computer science at the University of Texas at Austin.

That progress has followed the projection of semiconductor pioneer Gordon Moore—in an observation known as Moore’s Law—that chip density (and therefore computing speed) should double every two years. Moore believed his law would hold at least through 1985, but it has largely continued to the present day. “The computing power of a single integrated circuit today is roughly two billion times what it was in 1960,” according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Yet there’s always been a limit to how far classical computation can go. One of those limitations was perhaps first stated by physicist Richard Feynman in the early 1980s. His explorations in quantum thermodynamics, electron-photon interactions, and liquid helium made him realize that the complex equations weren’t solvable by classical computers. It’s an issue of scale—quantum computing requires massive numbers of inputs that a classical computer, no matter how fast, will never efficiently handle.

But Feynman, then others, saw that quantum mechanics could offer a way out of the problem. What if we could make a processor that ran on the laws of quantum mechanics?

Instead of using bits of 0s and 1s, quantum computers use quantum bits (qubits), which behave in the odd fashion of electrons, photons, and other quantum particles. A qubit can store information as 0, 1, or a combined state (called a superposition) of 0 and 1. Qubits can also be connected, in a sense, so that a change in one qubit will affect another. A connected group of qubits “can provide way more processing power than the same number of binary bits,” according to MIT Technology Lab.

Quantum computers are not “just … like classical computers but faster,” says Chetan Nayak, technical fellow and corporate vice president of quantum hardware at Microsoft. “Quantum computers are an entirely different modality of computing.”

Nor do quantum computers simply try “every possible answer in parallel”—another misconception, says Aaronson. Instead, quantum computing is a “choreograph” of possible states for each qubit, where “paths leading to [the] wrong answer … cancel each other out” and “paths leading to the right answer should reinforce each other.”

That could open the era of problem-solving that people from Feynman onward have envisioned. To Aaronson, quantum computing’s greatest promise is “simply the simulation of quantum mechanics itself … to learn about chemical reactions … design new chemical processes, new materials, new drugs, new solar cells, new superconductors.” For DARPA, that means “faster automation, improved target recognition and more precise, lethal weapons,” and more robust cybersecurity, according to Defense News.

But the quantum states of qubits are also delicate, and disturbances (called noise) ranging from changes in light or temperature to vibrations can alter their superpositions—and result in errors. This tendency of qubits toward “decoherence” has been a major hurdle for quantum computing research and development. Today’s quantum processors are full of noise and error-prone.

That’s where Microsoft’s approach could have a distinct advantage over that of its competitors. Topological qubits employ a physical construction that builds in quantum stability. But topological qubits are hard to build, and their results are harder to measure—Microsoft’s qubit project is “the longest-running R&D program in Microsoft history,” says Nayak. As of last September, IBM and Google had built 127- and 72-qubit processors, respectively, versus Microsoft’s 8. If Nayak’s team can successfully build a more stable processor at scale it may, in its way, be as big a step in quantum computing as the transistor was in classical computing.

The question is whether Microsoft has truly built such a processor at all. On the same February day Nature published the company’s peer-reviewed paper (which stopped short of offering proof of its claim to have built a topological qubit), Microsoft posted a press release and met with a few hundred researchers and others to review the Nature paper and announce the team’s progress since the paper’s submission early last year.

The press release was triumphant: “Majorana 1: the world’s first Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) powered by a Topological Core, designed to scale to a million qubits on a single chip… With the core building blocks now demonstrated … we’re ready to move from physics breakthrough to practical implementation.” It sure sounded as if Microsoft had built a topoconductor.

As Aaronson wrote on his blog, Shtetl-Optimized, “Microsoft is unambiguously claiming to have created a topological qubit, and they just published a relevant paper in Nature, but their claim to have created a topological qubit has not yet been accepted by peer review.”

Henry Legg, a physicist at the University of St. Andrews, was more blunt: “The optimism is definitely there, but the science isn’t there.” A bit premature on Microsoft’s part, perhaps. Regardless, Aaronson hasn’t been this bullish on quantum computing in his 25-plus-year career. “This past year or two is the first time I’ve felt like the race to build a scalable fault-tolerant quantum computer is actually underway.”

Clarification, March 4, 2024: This article has been updated to clarify how a qubit can store information.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.