Black History Month is almost over and this year’s Presidents Day is gone, but February 28 marks the date that our first president reached out to America’s first famous black poet. On that day in 1776, George Washington, from his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sent a remarkable invitation to 23-year-old Phillis Wheatley, who had been kidnapped from her African village 15 years earlier.

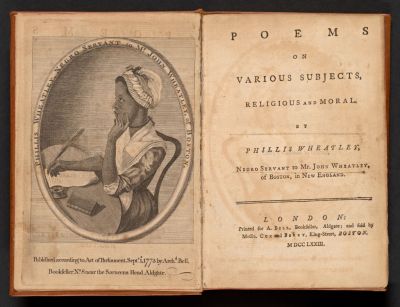

After surviving the Transatlantic crossing, Wheatley was sold to the Massachusetts household of John Wheatley. He, his wife, and their daughter soon realized that their new slave was brilliant. They excused Phillis from many household chores so she could learn not only English but also Latin and Greek. Soon, Phillis could read and understand difficult passages from the Bible and classical literature. And she began writing poems.

In 1772, 18 Boston leaders—including slave owners, ministers, and colonial governor Thomas Hutchison—assembled to investigate Wheatley. Blown away, they signed a letter acknowledging her brainpower and talent. The following year John Wheatley freed her, and in 1775 she wrote a poem that (in the exalted style of the era) described George Washington as “first in place and honours. … A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine, / With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.”

The poet sent her verses to the general on October 26, but her letter bounced around for six weeks before he read it, then he delayed responding. Washington finally wrote on February 28: “I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed … the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents.”

Washington’s reply also contained three remarkable details. First, he emphasized his desire to “apologize for the delay.” Second, he extended an invitation: “If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favourd by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations.” And third, he concluded: “I am, with great Respect, Your obedt humble servant, G. Washington.”

Unless Washington did not know Wheatley was black—that’s unlikely—he committed three “sins” that some of his contemporaries would have found unforgivable. Apologize to a black woman? Invite her to headquarters, where Washington was directing the siege of British troops in Boston? Finish with courtesies that treated her as an equal, and perhaps even more so?

We don’t know for sure if the meeting ever occurred, or what Washington and Wheatley talked about if it did. If the meeting took place, however, I hope she read him what became her most republished poem, “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” in which she expresses thanks about learning:

That there’s a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Pennsylvania Magazine in April 1776 published the poem, noting that the author was “the famous Phillis Wheatley, the African Poetess.” We don’t know if Wheatley’s poem had an effect on Washington, but during the Revolutionary War he suggested that slaves fighting on the American side receive their freedom. According to the historian Fritz Hirschfeld, Washington analyzed his own situation in 1778 and 1779, and he almost decided to abandon the plantation economy and try to operate Mount Vernon with paid labor.

Thereafter, Washington regularly thought about and investigated making the switch from slave owner to employer. In 1786 he said he was filled with “regret” about the institution of slavery and his role in it. He said “no man living wishes more sincerely than I do to see the abolition of it.” Washington kept wondering how to extricate himself personally. Morally, he objected to selling slaves, yet he was unwilling to take the huge economic loss involved in freeing them.

We can wish that he had, but Washington’s attitude was far different from Thomas Jefferson’s. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson classified African Americans as sub-human and wrote, “Never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never saw even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture.” Wheatley combined two of his dislikes, blackness and Christianity, so he sneered: “Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately; but it could not produce a poet.” Jefferson thought her poems “below the dignity of criticism.”

In 1791, the black almanac author Benjamin Banneker quoted to Jefferson his own words from the Declaration of Independence and eloquently challenged him to leave behind his “narrow prejudices.” Banneker wrote about human brotherhood: “however variable we may be in Society or religion … we are all of the Same Family, and Stand in the Same relation” to God. Jefferson held his fire for the moment but 18 years later was still irritated enough to sneer that Banneker had “a mind of very common stature” and must have used a white ghostwriter.

It would be inaccurate to say Jefferson was just reflecting the prejudices of his time or his social class. To take two examples, the wealthy South Carolinian John Laurens (11 years younger) favored emancipation, and Washington (11 years older) wrote differently. (Jefferson was a complicated intellectual whose heart and mind were not always in tandem, as I explain in my recent book, Moral Vision: Leadership from George Washington to Joe Biden.)

Washington died in December 1799. Thirteen months later Martha Washington, fulfilling her husband’s desire, freed the 123 slaves he had owned. I could stop with that happy ending, but Martha personally owned about 200 slaves, and they did not gain their freedom.

Nor was Phillis Wheatley’s life easy. She married a man who failed in business. Their three children all died young. In 1784, with her husband in prison for debt, she developed pneumonia and died at age 31. Nevertheless, the poet advised others and herself that affliction was temporary: “prepare to pass the gloomy night / To join forever in the fields of light.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.