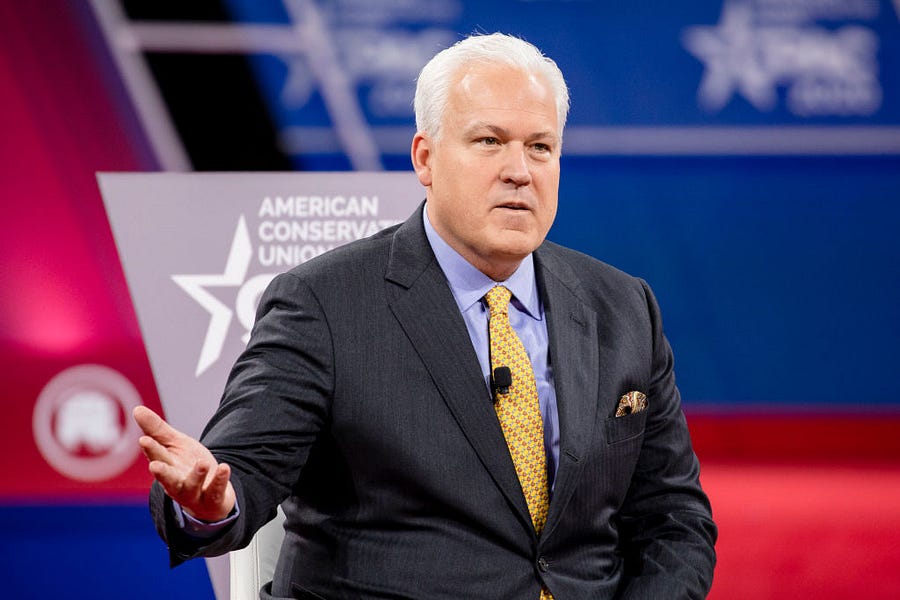

The American Conservative Union, the political organization helmed since 2015 by lobbyist Matt Schlapp, is best known for its Conservative Political Action Conference and its annual scorecard of the voting records of politicians in D.C. and across the country. But the ACU has recently found itself facing unwelcome scrutiny over a smaller aspect of its work: making the occasional endorsement in congressional races.

Sources tell The Dispatch that federal investigators are currently looking into possible criminal campaign-finance misdeeds at ACU during Schlapp’s tenure. As part of the investigation, the FBI has interviewed former and current ACU employees about the financial dealings of the organization and its leaders—and in particular, as one source said, about their “knowledge of the events leading up to the endorsement of Brian Kelsey.”

Who is Brian Kelsey? He’s a Tennessee state senator who in 2016 was trying to secure the Republican nomination for the open seat in his state’s 8th Congressional District. Beginning in July 2016, Kelsey made a series of odd financial moves. As reported by the Tennessean, his state Senate campaign sent more than $100,000 to a political action committee, the Standard Club PAC, affiliated with a Nashville members-only club. That PAC then sent $37,000 to a federal PAC called Citizens 4 Ethics in Government, which then turned around and sent $36,000 to the ACU. The Standard Club PAC also sent $30,000 to the ACU directly.

Immediately thereafter, the ACU, which had endorsed Kelsey in the federal race shortly before, inked an $80,000 radio ad buy trumpeting him as the race’s true conservative champion. “It is often difficult to cut through confusing campaign rhetoric to figure out which candidate is the best conservative in a race, but we think this is actually an easy call,” Schlapp said in a statement at the time. “If voters in western Tennessee are looking for a proven leader with a conservative track record, the decision is easy. Brian Kelsey is the real deal.”

Kelsey went on to place fourth in the primary, won by Republican David Kustoff, who represents the district to this day.

Neither the Standard Club PAC nor Citizens 4 Ethics in Government were high-dollar funds with large sums going in and out: Kelsey’s six-figure donation was the only one the Standard Club PAC received during the relevant reporting period. A nonpartisan watchdog organization, the Campaign Legal Center, filed complaints against Kelsey, the ACU, and various other alleged participants in the scheme to the Federal Elections Commission and to the Department of Justice in 2017, arguing there were “strong grounds to believe” that the participants had “engaged in knowing and willful violations of the federal campaign finance laws.” The CLC filings, based on Kelsey’s financial disclosures and reporting in the Tennessean, alleged that Kelsey appeared to have financed his own endorsement by a supposedly independent third party, with the money trail obscured through several shell PACs. What’s more—and from the point of view of federal election law, this is the salient point—the CLC alleged Kelsey appeared to have financed that in-kind contribution to his federal campaign with money from his state accounts, which is prohibited by law.

In addition to the state-to-federal campaign issue, they argued, the flow of money strongly suggested that ACU had coordinated with the Kelsey campaign in its ad expenditures, making that spending a forbidden in-kind contribution.

Both the FEC and the DOJ have enforcement authority over such acts; the FEC in matters of civil enforcement, the DOJ when a criminal investigation is warranted. It’s previously been reported that the feds had begun to look into Kelsey; in 2019, the Tennessean again reported that a grand jury investigation had been launched into the campaign, with several former state lawmakers telling the paper they’d been interviewed by the FBI about their knowledge of Kelsey’s campaign activities. (FEC proceedings are confidential until they conclude as a matter of law.)

Despite the alleged ACU connection, the matter remained a local-news concern at the time. The FEC complaint was striking, but—as one Republican operative put it in conversation with The Dispatch—“if you make a litmus test for all political operatives that they were involved in some sort of FEC question, you’d run out of people to interview real quick.” Kelsey wasn’t a national figure—he hadn’t even won his primary—and the Tennessean’s reporting about the FBI investigation focused on a part of the complaint that involved Kelsey and his fellow state politicians. (The complaint also alleged, citing public records, that Kelsey had donated money from his state account to several of those politicians, who then made corresponding donations to his federal campaign—a pass-through similar to the one allegedly involving the ACU.)

Recently, however, federal investigators’ attention has turned to the ACU itself. Several sources with knowledge of the ACU’s operations at the time tell The Dispatch they have been interviewed by the FBI in recent months about their knowledge of the events leading up to the Kelsey endorsement.

“They asked me about Matt Schlapp and [ACU Executive Director] Dan Schneider’s involvement within the organization, how they were involved with the disbursements of money and the decision of who to financially support,” one source said. “One of the questions that really stuck with me was, ‘Was Matt Schlapp in those meetings when they decided who to endorse?’ I said yes. And they said, ‘So was he directly involved with the decisions to financially support the candidates?’ I said, I don’t know. And they said, ‘But would it be weird if Matt Schlapp didn’t know?’ I said yes.”

In a statement, the ACU downplayed the investigation. “ACU is one of the oldest and most respected conservative institutions in America,” ACU communications director Regina Bratton told The Dispatch Tuesday night. “We are aware of campaign finance allegations lingering from the 2016 election cycle that were reported in multiple press outlets after a Soros-funded group complained. We continue to believe ACU’s activities, which took place more than five years ago, were legally compliant. We have been assured that ACU is not a target of any review by the government at this time.” Schlapp and the ACU did not respond to specific questions about the nature of the investigation.

The Campaign Legal Center, which has received donations from George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, was founded by Trevor Potter, a Republican and former George H.W. Bush appointee to the FEC, and regularly makes FEC complaints against candidates of both parties. Recently, the CLC has publicly supported a number of Democrat-sponsored pieces of voting rights legislation.

One former ACU employee who was interviewed by investigators declined to comment on the substance of the FBI interview, but insisted Schlapp would not have participated in an illegal scheme.

“Matt Schlapp is one of the most fundamentally honest and genuine people I have ever worked for, and he has an integrity with how he lives life and does business that is rare, especially in D.C.,” the former employee said. “Matt had high expectations for his employees, he was tough when he needed to be, but he was always fair—anyone who truly knows Matt would tell you his motivation for his work comes from a love of God, his family, and his country, and I count it a privilege to have worked for him.”

The existence of an ongoing investigation into ACU hasn’t been previously reported, but rumors of turmoil at the organization have hovered in conservative circles in recent weeks. Sources familiar with the search say Schlapp had been under consideration for the top job at the Heritage Foundation, but that the investigation was a factor in the think tank’s not advancing his candidacy.

Another unusual detail about the ACU’s involvement with Kelsey’s campaign is the role played by then-ACU employee Amanda Bunning. As director of government affairs, Bunning was involved in the group’s spending on races like Kelsey’s; she signed the FEC disclosure form for the $80,000 radio ad buy at the center of the complaint. Bunning left the ACU in March 2017; less than a year later, she and Brian Kelsey were married. (The Kelseys declined to answer questions about the timing of their relationship; instead, Brian Kelsey provided The Dispatch with the same statement he has given to other outlets over the years: “I welcome any investigation because all donations were made in compliance with the law and on the advice of counsel.”)

It’s possible that, even if investigators found proof of wrongdoing by anyone involved with the alleged scheme, it may be too late to bring criminal or even civil charges. The “over five years ago” in the ACU’s statement to The Dispatch is significant; the statute of limitations for most campaign finance crimes is five years. Sources who spoke to The Dispatch say they were interviewed by the FBI early this summer; the transactions between the Kelsey campaign, intermediary PACs, and the ACU took place in July 2016, which is indeed now just over five years ago.

The statute of limitations expiration isn’t a slam dunk, though; federal defense attorney Ken White tells The Dispatch that the feds often find ways to skirt it.

“It depends really on whether they have any ongoing conduct,” White said. “For the statute of limitations, one of the many things in the feds’ bag of tricks is using ongoing conspiracies. Let’s say the ongoing conspiracy is to engage in defrauding the federal government in making false FEC filings: The statute on that conspiracy claim doesn’t begin to run until the last overt act in support of the conspiracy. So commonly, you do the FEC filings, and maybe you send someone money that’s the proceeds of the crime. Or you tell someone, ‘don’t talk to the cops’ in order to conceal the crime. Whatever it is, so long as they have some continuing overt acts that are within the five-year statutory window, they can charge the conspiracy.”

However the investigation ends, it won’t simply fade unnoticed into the ether. Adav Noti, chief of staff at the Campaign Legal Center and a longtime FEC lawyer himself, told The Dispatch that the FEC has not yet notified them of an ultimate adjudication of their complaint: “The only thing I would say is that complaint has been pending with the FEC a very long time. The FEC is slow, but even by FEC standards, it’s been pending a really long time.”

In cases where a criminal investigation takes place, Noti said, the FEC will typically suspend its version of the proceeding until the DOJ has wrapped its case. If the DOJ ultimately decides not to charge anyone with anything, a public acknowledgment of the FEC closing the case wouldn’t be too far behind. That hasn’t happened yet.

“The allegations in our complaint—they’re really quite bad,” Noti told The Dispatch. “This is not run-of-the-mill shenanigans. It’s true that $100,000 isn’t an overwhelming amount of money, but it’s not nothing for a congressional race in Tennessee, either. And the two-part scheme to route it back to the campaign—if that is indeed what happened, it’s a very serious violation. It’s not a ticky-tack or a technical issue.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.