Science, in principle, is self-correcting. New evidence can baffle and challenge the scientific consensus of a given moment. This process has led to some of the most important scientific discoveries of our time. It’s no surprise, therefore, that taxpayer support for biomedical research remains a bipartisan issue.

Since 2015, for example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—the federal agency tasked with funding and supporting U.S. biomedical and public health research—has seen its budget increase under both Republican and Democratic presidents and congressional majorities. And for good reason: With an annual budget of nearly $50 billion, the NIH is the largest individual funder of biomedical research in the world. Yet despite this long history of support, the House Energy and Commerce Committee (ECC) released a proposal earlier this month to significantly reform the NIH, structurally and policy-wise. In an op-ed accompanying the proposal, Reps. Cathy McMorris Rodgers and Robert Aderholt argued that reforming the NIH is long overdue. As they note, “For every dollar used ineffectively, crucial knowledge, cures, and treatments are delayed or permanently abandoned. So it is in the public interest that the NIH works efficiently, effectively, transparently, and — above all — responsibly.”

Cynics might interpret the move as politically motivated, but doing so ignores that the NIH has operated with minimal congressional oversight for years. It has often resisted calls for increased transparency, even when questioned about potentially dangerous research or funding a researcher convicted of sexual abuse. Moreover, it has not been evaluated since the largely successful NIH Reform Act of 2006. Rodgers, Aderholt, and others insist that a congressional evaluation of the NIH is needed to keep the U.S. a world leader in biomedical science.

As Reps. Rodgers and Aderholt note, reform is difficult but has to start somewhere. The proposed House ECC framework includes several logical reforms that could significantly improve the NIH and its funding process—but it also includes some perplexing reforms that might lead to unintended negative consequences. Nevertheless, the fact that both the Senate and the House are trying to collaborate with the scientific and public health communities on NIH reform is a welcomed development.

Some limited structural reforms.

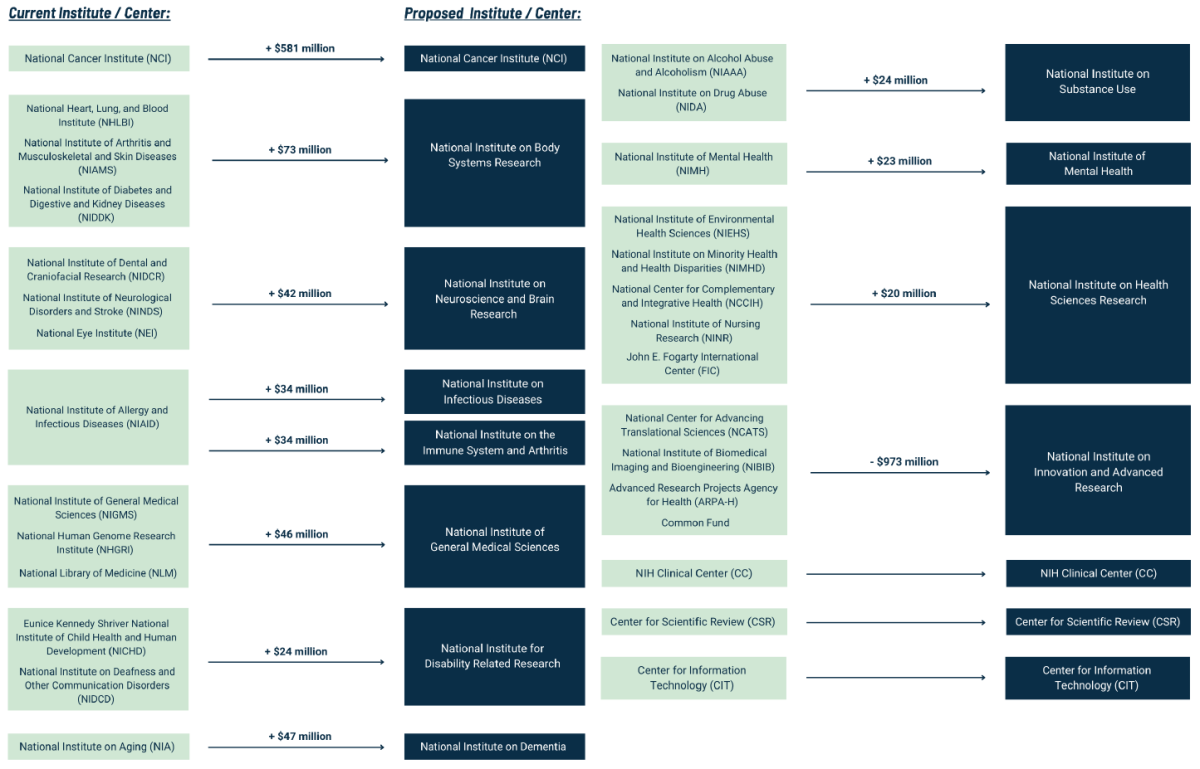

The House ECC proposes both “structural” and “policy” reforms to the NIH. The structural reforms attempt to simplify the expansive and often byzantine structure of the agency’s bureaucracy which, in its current form, consists of 27 distinct Institutes and Centers (ICs), each receiving money from the greater NIH budget and setting funding priorities at the behest of that IC’s director. Those funding priorities will occasionally include Congress-directed initiatives, such as the bipartisan Cancer Moonshot, which was funded through the 21st Century Cures Act. Beyond these initiatives, however, most biomedical research funding is awarded by an IC via one of many recurring competitive granting mechanisms, such as the NIH’s Research Project Grant.

The House committee is proposing to consolidate the 27 ICs into 15 ICs to better coordinate their work, though it’s unclear whether such restructuring can achieve this lofty goal. Still, as the current ICs have expanded their scope and mission, it has led to the creation of sprawling intramural bureaucracies with often overlapping funding priorities and narrow research goals.

Although the new ICs would consolidate previously smaller ICs to help update and focus priorities on pressing health issues, the House committee’s framework fails to directly address bloated intramural spending (i.e., money spent on research and other activities at a NIH facility), which accounts for 10 percent of NIH spending. Perhaps the structural reforms will indirectly lead to reduced intramural spending by addressing redundancies, but this remains to be seen.

Amid the consolidation, one notable exception is the expansion of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases into two different ICs: one for infectious disease and one for the immune system in non-infectious disease settings and arthritis. It’s a commendable change that will broaden our understanding of the different roles of our immune system. Nevertheless, including arthritis in the second IC’s mission is problematic. That’s because the disease is also included in the new National Institute on Body Systems Research and seems to unintentionally exclude the extensive public health and economic burdens caused by autoimmunity and chronic inflammatory diseases. If restructured in this way, money that currently goes to prevalent diseases, such as Lupus, might decrease which would cause the research to find treatments or cures to stagnate.

Potentially consequential policy reforms.

While the structural reforms are more noticeable, the policy reforms are more extensive and would likely have a broader impact on the biomedical science enterprise. The House committee’s recommendations include mission and leadership reforms, funding reforms, and grant reforms.

Many of the mission and leadership reforms relate to Congress reasserting its Article I authority to increase NIH transparency and responsiveness to oversight. For instance, the proposed framework recommends establishing a commission—similar to the Scientific Management Review Board (SMRB) that resulted from the 2006 reforms—to perform regular NIH-wide reviews that evaluate the agency’s performance and provide recommendations for improvement. The House committee also recommends a five-year term limit for IC directors, eligible for extension pending approval of the NIH director.

Combining the proposed structural changes and IC director term limits could help ensure that the ICs are nimble, well-informed, and capable of incorporating the latest scientific advances and knowledge to set their mission and funding priorities. The limited-tenure leadership approach is also common in private academic medical centers because it helps to ensure biomedical research innovation and cutting-edge medical care. On the other hand, introducing term limits might lead to difficulties in recruiting and retaining talented leaders.

The House committee’s proposed funding reforms are fewer but no less potentially impactful. First, the framework recommends the repeal of the Public Health Service (PHS) Evaluation Set-Aside (aka PHS Evaluation Tap). The PHS Evaluation Tap is a means to transfer funds previously appropriated to one PHS agency to another with minimal oversight. As the House ECC framework notes, over $1.4 billion was transferred to the National Institute of General Medical Science (one of the NIH ICs) in 2024 alone. Second, it recommends establishing a policy to limit or standardize the monies added onto a research grant that goes to the researcher’s institution to cover expenses associated with performing NIH-funded research.

This facilities and administrative (F&A) rate, negotiated between the NIH and the institution, is often a significant sum. F&A costs are important because they allow an institution to support biomedical research: the cost of the lab space, for instance, or the salary of administrative support staff. (Think of F&A costs as your rent, utilities, etc.) To take one example, Harvard Medical School’s F&A rate, generally similar to competing institutions, is 69.5 percent. That means a $300,000 grant would include an additional $208,500 that goes directly to the researcher’s institution. The House committee recommends not only revisions to how these rates are determined but also increased transparency and reporting requirements on how such funds are spent.

It’s unclear how capping or changing the formula for determining F&A rates will affect overall costs. Doing so could free up more funds to directly invest in biomedical scientists. It’s also possible that institutions currently relying on higher rates will overcorrect in a way that reduces hiring and support for young investigators who generally perform the most cutting-edge science. Regardless, it’s reasonable for Congress to demand an accounting for facilities and administrative spending, similar to the yearly reporting required of NIH grant recipients.

Finally, the House committee addressed one of the most discussed, and arguably most controversial, topics within biomedical science: grant reform. For understandable reasons, the committee’s framework spends significant ink identifying the many reasons why grant reform is necessary, many of which are criticisms made by biomedical scientists. The proposed reforms are extensive, including a cap on how many grants an investigator can receive; increased financial support for early-career scientists and systematic replication studies; establishment of an independent external review board to oversee and implement concrete policies governing “risky gain-of-function” research; and incorporation of policies protecting U.S. national security interests.

The proposed cap on how many grants an investigator can receive is not without precedent. In 2017, the NIH attempted to cap investigator grants because, as then-director Francis Collins noted, 40 percent of NIH awards went to 10 percent of investigators. The plan faced fierce objection and was eventually abandoned. It’s worth considering, however, why even modest-sized labs are forced to apply for an increasing number of awards. As research costs and staff salaries increase, the value of the average NIH Research Project Grant, which has remained the same for decades, is diminished. Also, any grant cap policy will inherently lead to a cap on investigator salaries. This could lead to a brain drain of ambitious scientists away from academic biomedical science into industry, with potentially catastrophic consequences not just for the NIH goal of advancing knowledge to improve human health but also for the significant economic value of NIH-funded research. Ultimately, what such grant reforms will entail is unknown, but the NIH and biomedical scientists recognize the time for change is now.

Many biomedical scientists will be understandably wary of Congress assuming increased oversight of their work. But such a view ignores the reality that NIH-funded biomedical scientists rely on a finite pool of taxpayer dollars. The interests of those taxpayers, and by extension their representatives, must be considered. The proposed reforms don’t seek to impose an undue burden on the majority of biomedical science, but instead to provide oversight on issues of national importance. Whether or not these proposed reforms have their intended effect likely depends on the level of enforcement power Congress grants to external review boards. Regardless, increased transparency at the NIH is clearly warranted.

Science and Congress should collaborate.

In 2008, Dr. Elias Zerhouni, the NIH director in charge of implementing the NIH Reform Act of 2006 under President George W. Bush, highlighted the numerous benefits realized by Congress-enacted reforms. Many of the reforms allowed biomedical scientists to build on those early successes to make profoundly important discoveries and create transformational inventions. The focus on innovation and support for high-risk, high-reward science helped creative scientists conduct exciting biomedical research through grant programs such as the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (an award I count myself lucky to have received).

However, like the scientific process itself, the 2006 reforms were not perfect and much has been learned from its successes and failures—especially regarding NIH transparency and accountability. Despite sincere attempts to address these two goals, lingering issues remain and new ones have arisen.

It’s reasonable to expect that any federal agency receiving taxpayer money—let alone tens of billions of dollars a year—be open to external oversight and reform. For many biomedical scientists, the notion of external oversight and reform is familiar. Most nonprofit academic medical centers, for instance, establish external scientific and financial advisory boards to help drive innovative science and patient care while ensuring fiscal health. As Rep. Rodgers said, “Our door is open. Work with us. Be a partner.” Biomedical scientists would do well to heed her words.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.