After days of cantankerous partisan bickering, House Resolution 748—the CARES Act—was finally nearing the finish line, with a vote in the Senate expected later in the evening. But just after 1 p.m. on March 25, a press release hit the inboxes of socially-distanced political reporters scattered across the nation’s capital.

“A massive drafting error in the current version of the coronavirus relief legislation could have devastating consequences,” wrote a trio of Republican senators. Washington held its breath. The legislation at hand—which would pump upward of $2 trillion into the hands of workers and businesses dealing with the abrupt shuttering of much of the country’s economy—had finally, after much back-and-forth, been agreed to by leadership in both parties, and time was of the essence. The American people couldn’t afford another setback.

Sens. Ben Sasse, Tim Scott, and Lindsey Graham continued: “Unless this bill is fixed, there is a strong incentive for employees to be laid off instead of going to work. This isn’t an abstract, philosophical point—it’s an immediate, real-world problem. If the federal government accidentally incentivizes layoffs, we risk life-threatening shortages in sectors where doctors, nurses, and pharmacists are trying to care for the sick, and where growers and grocers, truckers and cooks are trying to get food to families’ tables.”

Within a few minutes, it became clear the provision to which they were referring was not a “drafting error,” but rather a deliberate addition to the legislation—pushed by Democratic Sens. Ron Wyden and Michael Bennet—that was hammered out in the negotiation process.

Through July 31, 2020, according to Section 2104 of the bill, Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation would total each state’s typical benefits, “plus an additional amount of $600” per week. And the legislation broadens these benefits to independent contractors, part-time workers, and those in the gig economy as well.

“We’re doing everything we can to get out ahead of what’s going to be a severe economic crisis, and step one is securing the most significant expansion of unemployment insurance in history,” Wyden—who had wanted the changes to be made permanent—said in a statement. “This is just one part of the overall effort to get through this oncoming crisis, but it will help millions of Americans stay in their homes and put food on the table.”

The Trump administration—represented in negotiations by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin—agreed, for the most part. “We wanted to have enhanced unemployment insurance,” Mnuchin told reporters. “Most of these state systems have technology that’s 30 years old or older. So, if we had the ability to customize this with much more specifics, we would have. This was the only way we could assure that the states could get money out quickly in a fair way, so we used $600 across the board. And I don’t think it will create incentives. Most Americans, what they want, they want to keep their jobs.”

The three aforementioned Republicans were later joined by Sens. Rick Scott and Ted Cruz in their crusade, and introduced an amendment that would cap unemployment benefits at 100 percent of the wages workers were receiving prior to the coronavirus-induced economic shutdown. While workers cannot “lay themselves off” and aren’t eligible for unemployment benefits if they quit their job, the senators wanted to ensure that already laid-off Americans—with the additional $600 per week—would not be disincentivized from rejoining the workforce once businesses could afford to hire again. “There are pieces of this bill that are broken and that we can fix tonight,” Sasse said in a speech on the Senate floor. “This bill as currently drafted creates a perverse incentive for men and women who are sidelined to then not leave the sidelines and come back to work.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders took to the floor as well. “Some of my Republican colleagues are very distressed, they’re very upset that somebody who’s making 10, 12 bucks an hour might end up with a paycheck for four months more than they received last week,” he said, his voice dripping with sarcasm. “Oh my God, the universe is collapsing.”

The amendment failed, 48-48. All five of the Republicans voted for the CARES Act anyway, which passed 96-0. (Four senators were self-quarantining and unable to vote.)

Fast forward two weeks. At least 10 million Americans have been rendered unemployed, essentially overnight.

Jake Hanson—a department head at a Hobby Lobby in the Dallas/Fort Worth area—was furloughed after the arts and craft chain decided (belatedly) to close all its stores in the face of the coronavirus threat. The father of three is deciding what to do next.

“As I look at it, I’m thinking like, ‘Okay, I can try to get a job—there’s no guarantees—I can try to get a job at Home Depot, make $16, $17 an hour,’” he told The Dispatch in an interview on Monday morning, after unsuccessfully trying to pin down a Home Depot store manager. “Then I started looking at the unemployment benefits. My last paycheck for Hobby Lobby for two weeks was about $1,000. And I’m looking at the stimulus plus unemployment, all this. And it’s almost $1,000 a week if my calculations are right. So, I’m getting a pay raise by being unemployed, if everything comes through like I expect it to.”

Hanson described himself as a “pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps” kind of guy. “I want to be a responsible person, I’m a hardworking person, and want to do my part to take care of my family,” he said. But “the incentive—or the pull for me is strong to just say, ‘Okay, I’m going to take a nice paycheck, it’s double what I’ve been making the past few weeks.’”

Especially when the alternative requires interacting with hundreds of strangers every day, flying in the face of current public health guidelines. Hanson said he didn’t notice most Home Depot employees wearing masks or taking other precautions when he stopped by the store. “There are dangers … working even in a place that’s ‘essential,’” he added. “That’s definitely another factor involved in the whole thing.”

And Hanson is far from alone. Sam Chamberlin worked as a behavioral therapist for preschool-aged children with autism in Wisconsin until his center closed down last month. After maneuvering through a system he concluded was “designed intentionally to be difficult,” he received his first-ever unemployment check last Monday. “It felt very shameful,” he told The Dispatch, citing the repeated warnings he encountered while applying for benefits that threatened fines and jail time if he filed incorrectly.

While he disclosed he was making about $1,000 every two weeks in his previous role, Chamberlin estimated the boosted unemployment insurance will now pay him $1,760 over the same time period. He hopes he’ll be able to return to his “current/former employer” by the time these benefits are set to expire at the end of July, “but it’s hard to know for sure.”

“It’s kind of coasting. There’s no job search requirement, which is good, through unemployment. So I’m not actively searching,” he said. “It’s kind of a weird limbo. I feel like I should be doing more, but I very much liked my job before, and I would like to return to that job. … There’s a fair amount of room for movement upwards, and I was actually supposed to begin training for a promotion on the Wednesday, the first day that we closed.”

Plenty of people—like Michael Gallipo of Rochester, New Hampshire—would not hesitate to take a job, even if CARES Act benefits paid more. Gallipo had just wrapped up eight months of contract work as a web developer—a field he is relatively new to after spending most of his career in finance—and was in the process of looking for a permanent position. But once coronavirus hit, he began to hear of many more experienced developers than him being laid off, saturating the labor pool. “I’m going to keep trying,” he told The Dispatch, “but it’s going to be a hard slog.”

Congress put together a “pretty attractive benefit,” he suggested, adding that, between the New Hampshire assistance and the extra $600, “it’s probably not dramatically different than I was making as a contract employee—which I think was the intent.”

But he’d rather work and bolster his resume. “If I can land something,” Gallipo said, “even if financially it’s no better—or maybe even a little worse—than staying on unemployment, I’ll take the job.”

Some smaller employers have concerns over how these new unemployment benefits will interact with their newfound Paycheck Protection Program liquidity. Steve Novak—president of a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that operates a child daycare center deemed “essential” in Maryland—told The Dispatch he’s had to lay off “quite a bit of staff” as their enrollment numbers plummeted from 100 students to 25.

“I think there’s five or six [workers] that went out on unemployment,” he said. “And they’re making more than they made when they were working for us. And so that is the question … will they come back?”

“If given the choice,” he added, “I think most of the employees—and maybe when they find out they’re making more, maybe they’ll change—but I think the employees want to stay on. They didn’t want to claim unemployment. We have long-term employees, people that have been with us for 10 years at this facility.”

At a time of unprecedented economic uncertainty, no one can or should blame workers for taking full advantage of the benefits made available to them through July. In fact, the generous unemployment package was designed to serve dual purposes: Not only will workers out of a job be able to continue feeding their families, paying their bills, and spending in their local communities, but the increased weekly dollar figure could play a role in flattening the coronavirus curve by keeping more Americans at home.

But the Republican senators’ concerns with the plan were far from baseless. Although the expanded benefits are set to expire in a few months, our comatose economy is being propped up by a small subset of workers—health care professionals, truck drivers, grocery store cashiers—and would further implode if they decided to stay on the sidelines, though there’s thankfully little evidence of that yet. The eventual recovery—whenever it comes—will inevitably take much much longer if workers are completely untethered from their places of employment. And for small businesses essentially barred from generating revenue at the moment, the typical progressive refrain of “raise wages” falls on deaf ears.

“We’ve got to make sure that slapdash policies from Washington don’t increase America’s pain and suffering by prolonging long-term unemployment,” Sen. Sasse told The Dispatch. “Workers who lost their jobs should get 100 percent of their pay with generous unemployment benefits during this emergency, but Washington shouldn’t incentivize unemployment when we’re on the brink of economic meltdown. We ought to be celebrating the dignity of work—the heroes driving trucks, stocking shelves, or delivering medicine. Those jobs can’t be done from a laptop at the kitchen table, but those jobs are keeping this country alive.”

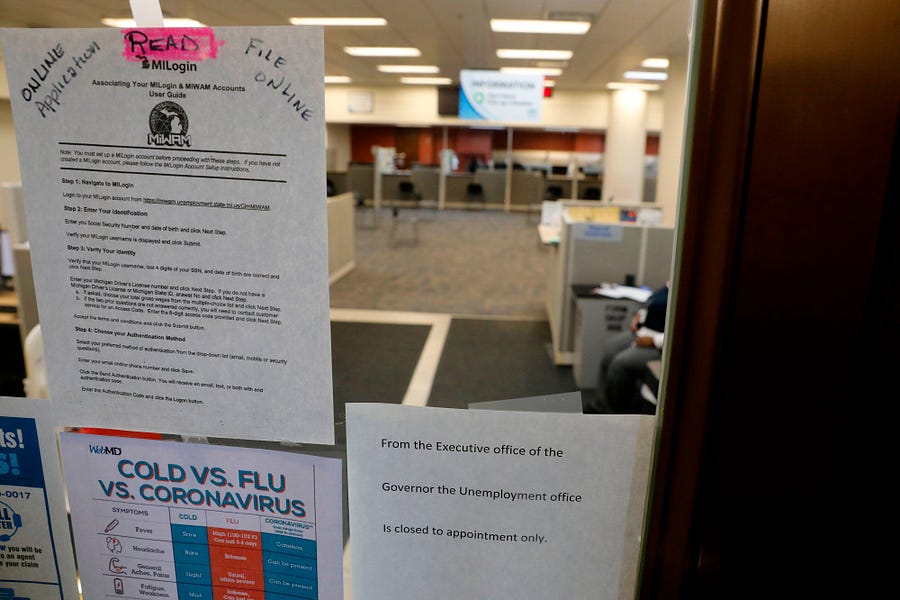

Photograph of a closed unemployment office by Jeff Kowalsky/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.