Editor’s Note: In addition to his work at The Dispatch, Kevin D. Williamson is a writer in residence at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, in which capacity he has written about a number of subjects, including climate policy and regulation, for a number of publications. This series on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) and firearms regulation is part of that work. Today’s installment looks at how the ATF regulates gun purchases through tax collection.

Part 4: The View From the Back Office

Part 5: But for Some Flubbed Paperwork …

For about 200 years, the United States of America got along without the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. And, for much of that history, most Americans lived under a firearms-regulation regime that was relaxed or, in many places, effectively nonexistent. It is worth considering that there is a parallel between the Second Amendment and the First Amendment, with early firearms regulations often taking the same form as permissible restrictions on speech and other communication: time, place, and manner regulations. Americans had generally unrestricted rights to acquire firearms but might have been prohibited from carrying them in certain urban areas or restricted places (such as saloons) or while drunk, which was a real consideration in the hard-drinking 19th century.

The progenitors of the ATF were all fundamentally tax collectors and assistants to tax collectors. The earliest bureaucratic ancestor of the modern ATF was the Revenue Laboratory established within the Treasury by Congress in 1886, whose role was to examine alcoholic products (and suspected alcoholic products) to ensure that all of the necessary duties had been paid and that the products were otherwise in compliance with federal regulations.

“The revenue isn’t the point—ATF collects only about $100 million a year in revenue from taxes authorized by the National Firearms Act but has a budget of $1.4 billion. The point is creating regulatory burdens to keep Americans from doing things certain people in the government don’t want Americans to do without explicitly prohibiting those things.”

As we have seen in other instances—notably in the case of the Affordable Care Act—when Congress cannot find a plausible constitutional basis for some action its members wish to undertake, that action often is repackaged as a tax, with the Supreme Court having long conceded congressional taxing authority to be effectively unlimited and plenipotentiary. Before the ratification of the 18th Amendment and the launching of Prohibition, federal alcohol regulation had largely been enacted through tax policy, to such an extent that in the early 20th century, as much as 40 percent of federal revenue came from taxes on alcohol. As documentarian Lynn Novick (Ken Burns’ partner in Prohibition) points out, it was the enactment of one keystone progressive policy—the income tax—that enabled Prohibition, another major progressive priority at the time.

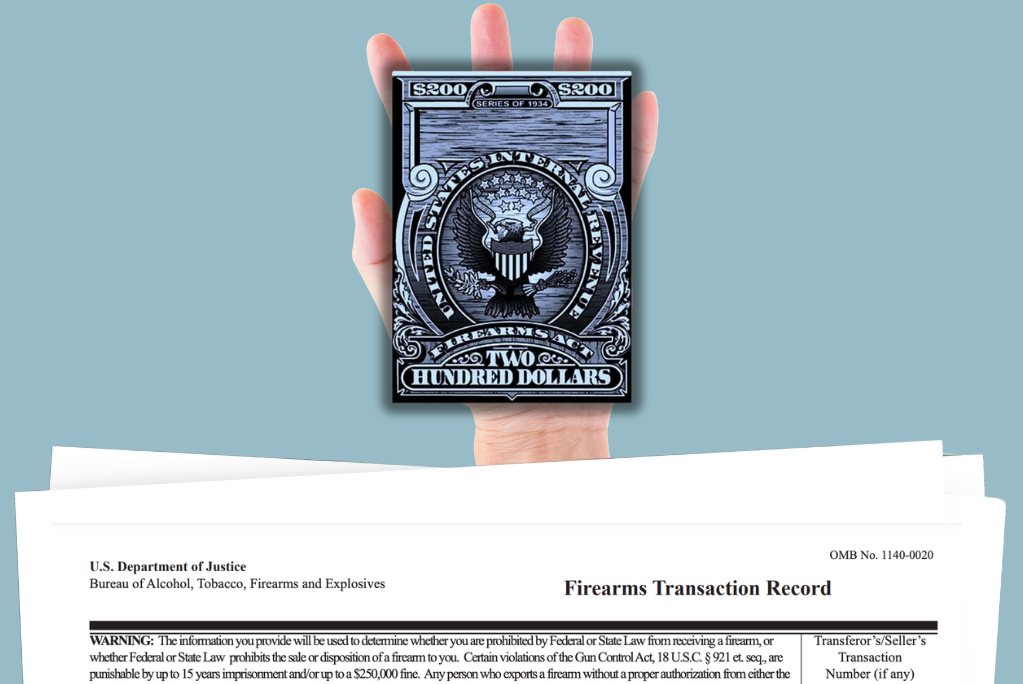

A similar tax-as-regulation model has long been applied to firearms: To this day, the federal permission slip one needs to legally possess certain firearms (such as short-barreled rifles) or appliances (such as acoustic suppressors) is a tax stamp, certifying that some small tax ($200 for most items) has been paid. Of course, the revenue isn’t the point—ATF collects only about $100 million a year in revenue from taxes authorized by the National Firearms Act but has a budget of $1.4 billion. The point is creating regulatory burdens to keep Americans from doing things certain people in the government don’t want Americans to do without explicitly prohibiting those things, i.e. treating the power to tax as a backdoor to the power to regulate where that regulation might not otherwise pass constitutional muster.

I will give you a personal example: A couple of years ago, I bought a .45-caliber handgun that I wanted to put a shoulder stock on. Unless the barrel is at least 16 inches long, a handgun with a shoulder stock on it is a “short-barreled rifle,” one of those special categories of highly restricted weapons under the National Firearms Act. You can buy a firearm with the stock already attached, in which case you fill out one kind of form, pay the tax, and wait however many months (sometimes more than a year) for the ATF to give you your tax stamp; or, if you prefer (because it often is faster) you can buy the firearm and the stock separately and fill out a different ream of paperwork—one that makes you a firearms “manufacturer” whose manufacturing activity consists of fastening two screws one time—and pay your $200 and wait however many months it takes. You also have to get yourself fingerprinted, submit a passport-style photo, etc. I am a reasonably smart guy, and I didn’t get my manufacturing paperwork right on the first try—ATF rejected it. (My omission? I did not put “US” before the serial number.) If I fasten those screws without my tax stamp, I am a federal felon. I also have a wife, three jobs, and four children, and so doing the paperwork a second time has not risen to the top of my agenda in the year or more since then. And that is how you use regulation to enact a soft prohibition when you cannot enact a legal one.

ATF’s primitive regulatory ancestors were hatched at Treasury and moved around from department to department over the years until something like the modern agency was birthed within the IRS—as the Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Division of the Internal Revenue Service—with the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968. ATF became an independent bureau shortly thereafter, on July 1, 1972. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 moved ATF from Treasury back to Justice. And that may have had some real influence on how the agency does its business, inasmuch as the Justice Department is generally understood to be more political than Treasury, and more responsive to the political needs of the president.

And that matters.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.