History is political because people are political.

That’s true in the objective sense. You can’t study the story of the human species without giving heavy consideration to the piteous labors of 10 millennia of trying (and usually failing) to find a happy balance between freedom and order in our lives together. History can and often has gone too far in emphasizing governments and leaders rather than people, but there’s no way to tell the story of us without telling the story of our politics.

But it’s also true that history is political in the sense that the way we study and discuss our history shapes and is shaped by the politics of our moment. We see the past differently based on current events—a sudden fascination with the Spanish flu of 1918, for instance—but we also see current events differently because of how we understand or misunderstand history.

When we hear something is “unprecedented,” it usually means the person describing the event doesn’t know history. And even when something truly is a radical departure, like an American president trying to steal a second term and his supporters sacking the Capitol, there are always echoes from the past. We’ve met versions of Donald Trump before in our own story over and over and over again. Not knowing that makes us not only more susceptible to the guiles of demagogues but less able to confront them after their rise.

When I was a boy in the 1980s, I lumped the Vietnam War together with Korea and World War II in my mind. But for the Americans of my parents’ generation, the conflict in Southeast Asia was less than a decade over and still a major force in shaping American politics and policy—much closer in time than 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq are to me now. Older people suffer from a recency bias that overestimates the importance of things that happen in their own lifetimes, while younger people suffer from a shortened perspective that suggests history started about five minutes before they were born.

We know the solution to these problems, though: A broad, inclusive, and honest study of history. Unfortunately, politics increasingly discourages or even forbids exactly the thing that would help us escape the maladies of our moment.

As the teaching of history has itself become a political issue, Americans have increasingly abandoned it as a tool and an area of study. Teaching honest history today can be a career ender or at the very least an invitation to unrest and discord. Educators interested in preserving their jobs and sanity would understandably shy away from the subject.

We don’t need statistics to know about the decline in the teaching of history in America’s schools and colleges. A casual conversation with most Americans under 30 will do the trick. But consider the National Assessment of Educational Progress’ most recent report card on 8th graders: Just 15 percent of all students could meet the meager standards to even be proficient in history. More than a quarter of all 8th graders weren’t getting a U.S. history course at all.

Schools and teachers are continually asked to do more, often with fewer resources. Educational fads, like the current emphasis on critical thinking, often come at the expense of the knowledge-based studies. Long ago, the shadier discipline of “social studies” crept in to replace the fundamental instruction in the whos, whats, whens, whys, and hows of history. Students get history detached from its practical connection to the present as a kind of dumbed-down sociology or anthropology.

The point of universal history education for children is purely practical. We should want all Americans to know the basics of how we got here and why, so that they can fulfill their obligations in a republic. It’s no surprise that Americans are so bad at citizenship given how little they know about it.

And academia’s abandonment of history is hardly a matter of middle schools alone. History is dying at America’s colleges and universities, too. The percentage of history majors among bachelor’s degree recipients has never been huge, but even before the pandemic had reached its all-time low in 2018.

Part of this is a bit of a mirage. Sociology, archaeology, and anthropology might be thought of as applied history, philosophy as the history of knowledge and ideas. Majors like literature, film, political science, and economics may lead to the practice of special skills, but begin and remain steeped in history.

And what are the students majoring in women’s studies, African American studies, Latin American studies, or Jewish studies really studying but history with blinders on? While we might be glad that people are studying some of the lessons of the past, we know that this bespoke approach to study is more likely to protect students and their teachers from the more challenging and valuable aspects of the broader discipline. The study of history provides great insights on the immutability of human nature. Tailoring it to extremely specific interests invites students to think about group identity rather than humanity. History-ish degrees that can be obtained without foundational survey courses may do more to distort students’ understanding of the story of our species than enrich it.

Part of the, ahem, end of history in academia may also be the increasing number of women going into hard sciences, mathematics, and business in recent decades. From 1971 to 2017, the increase in the female share of degrees in business went from 9 percent to 47 percent. Women now represent 79 percent of psychology majors, 64 percent of biological and biomedical majors, almost doubling their shares from a generation ago. Academics include history in the “social sciences,” which taken together are now slightly more female than male: 52 percent to 48 percent. But history itself is significantly more male than female in its students. In this way history as a major gets it on both sides: more competition for female students from professional and vocational disciplines but also from the bespoke, narrowed versions of history that have proliferated in course catalogs.

An even more significant problem for history is economic in nature. Since the financial panic of 2008 and the recession that followed, the shift away from all degrees associated with a liberal education was remarkable, but history suffered the most of all. From 2008 to 2017, history led all majors in the decline of degrees granted with a drop of about 30 percent. The decline became even steeper among those students who started college after the panic, and took down adjacent disciplines like religion, humanities, literature, and philosophy, which all dropped by more than 20 percent between 2011 and 2017. The fastest-growing fields were all in practical trades or professions: exercise science, computer science, nursing, health and medical, computer and electrical engineering, and engineering all saw increases of 50 percent or more in the same period.

And what has been happening to the cost of college all the while? Since 2003, tuition and fees at the top 440 schools in the U.S. News rankings have increased 134 percent at private colleges and universities to $44,433 per year. But the biggest hikes have been at public institutions: a 141 percent jump to $27,841 for out-of-state students and an eye-popping 175 percent to $11,541 for in-state students.

The inflation of the tuition bubble was substantially financed on student debt. If you’re taking on a huge burden for an education, especially in uncertain economic times, it’s a lot easier to rationalize paying for a degree that will get you a job, like being a trainer or a physical therapist, than a major that is only directly applicable in academia. And as students turn away from history as a major, the work of teaching it has fallen on hard times too.

But our historical ignorance is costing us dearly.

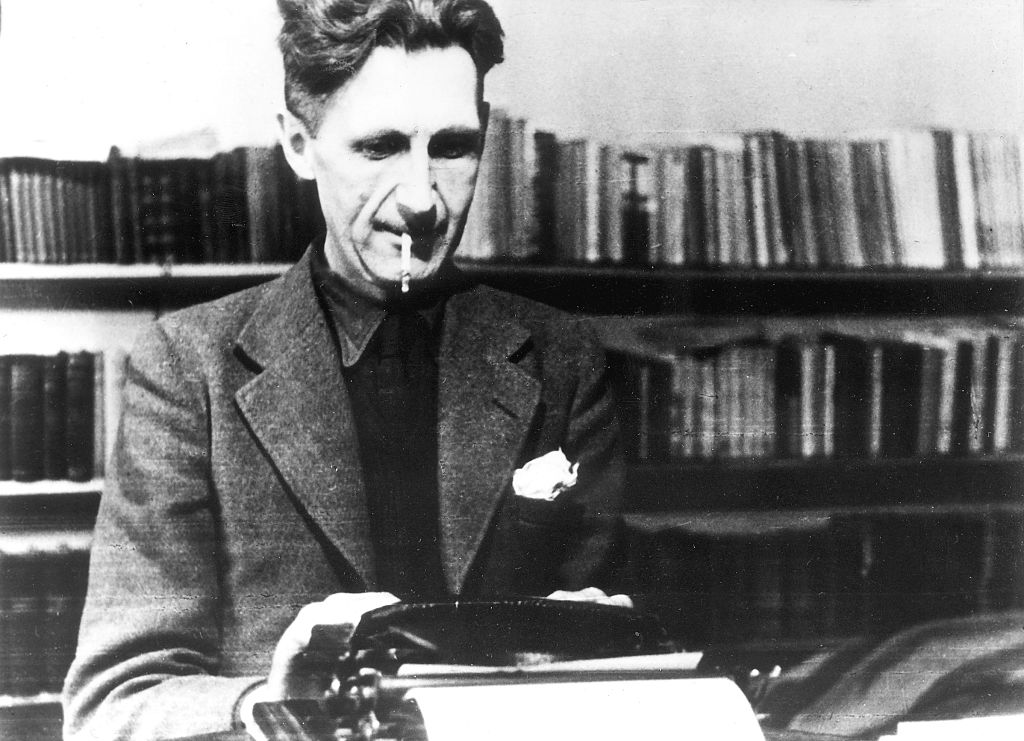

In 1942, George Orwell reflected on the power of history in his essay Looking Back on the Spanish War. Orwell had fought the fascists in Spain five years earlier, and wanted to explain how the free world had been so willfully ignorant of the threat from modern, mechanized tyranny.

“I know it is the fashion to say that most of recorded history is lies anyway. I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased,” he wrote. “But what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written.”

Alas, that abandonment did not end with Orwell’s age.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.