Two and a half years after Richard Nixon resigned the presidency after Watergate, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel under Jimmy Carter issued a memorandum opinion “concerning the constitutionality of H.R. 2819, which would establish an Office of Inspector General.” This little-known office within the Justice Department believed that the bill would “make Inspectors General subject to divided and possibly inconsistent obligations to the executive and legislative branches, violate the doctrine of separation of powers and are constitutionally invalid.” In 1978, the Inspector General Act passed by a vote of 388-6 in the House, by unanimous consent in the Senate, and was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter, who described it as “perhaps the most important new tools in the fight against fraud.”

Fast forward 42 years and questions surrounding the authority and independence of inspectors general is once again coming to a head.

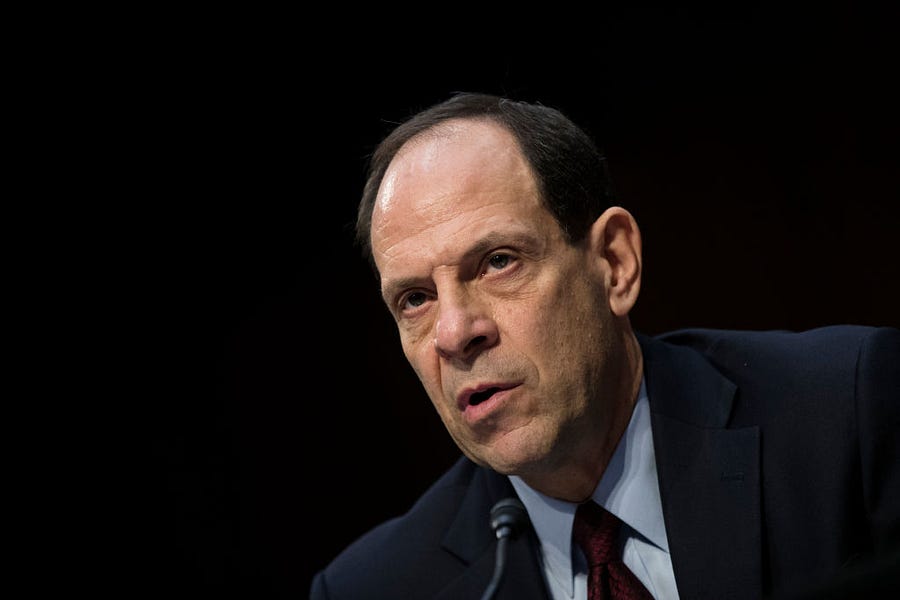

In the span of a week, President Trump removed two inspectors general. First he fired Michael Atkinson, the intelligence community’s inspector general who came to prominence for his role in notifying Congress of a whistleblower’s complaint related to funding to Ukraine, and then he removed acting inspector general Glenn Fine, who had been selected as head of the coronavirus spending oversight board to oversee the $2.2 trillion in the coronavirus rescue package passed by Congress. He also got into a back-and-forth during one of his daily briefings over the HHS inspector general’s report that “chronicled long waits for coronavirus test results and supply shortages at hospitals across the country,” denying the report and asking “could politics be entered into that?”

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley sent the president a bipartisan letter about Atkinson’s removal co-signed by seven other senators, correctly stating that “current law requires that you inform the Senate and House Intelligence Committees in writing of the reasons for your removal of the IC IG, at least 30 days prior to that removal” and asking him to “provide more detailed reasoning for the removal of Inspector General Atkinson [and] how the appointment of an acting official prior to the end of the 30 day notice period comports with statutory requirements.”

This has created the very constitutional pickle that DoJ flagged in 1977. Can Congress limit the president’s power to remove a member of the executive branch? At the time, executive branch lawyers said no in their memo opining on its constitutionality to Carter’s attorney general, arguing that “the power to remove a subordinate appointed officer within one of the executive departments is a power reserved to the President acting in his discretion.” And current Attorney General Bill Barr appears to agree. Appearing on Fox News, he said that Atkinson “was obliged to follow the interpretation of the Department of Justice and he ignored it” when he notified Congress of the then-reported contacts between Trump and Zelensky and that he believed the “president was correct in firing him.”

Trump, however, isn’t the first president to remove IGs. In 1981, President Reagan initially fired all the IGs that had been nominated by Jimmy Carter. And in 2009, President Obama provided the same vague explanation that Trump used to remove Atkinson (“loss of confidence”) when he fired an IG who had opened an investigation into a prominent political supporter.

But Democrats on the Hill are prepared to take action. In a letter to Michael Horowitz, the Justice Department’s inspector general who leads the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, 20 House committee chairs asked for “legislative and other proposals to increase your independence and protect you from retaliation, including but not limited to allowing for the removal of top Inspector General officials only for good cause.” They cited President Trump’s recent actions, which they described as reflecting “a campaign of political retaliation and reward that is antithetical to good government, undermine the proper stewardship of taxpayer dollars, and degrade the federal government’s ability to function competently.”

Even so, not all IGs are created equal. The 1978 act created 12 inspectors general, but today there are 74 throughout the federal government, including five within the legislative branch, with independent budget appropriations from Congress. The purpose of each is to detect fraud and abuse and keep Congress and agency heads informed about problems in their agency. A single IG can churn out hundreds of reports, reviews, and audits a year. This, of course, requires a large staff. Horowitz, for example, has more than 500 special agents, auditors, inspectors, attorneys, and support staff working for him at the Department of Justice. The appointments are supposed to be made “without regard to political affiliation and solely on the basis of integrity and demonstrated ability in accounting, auditing, financial analysis, law, management analysis, public administration, or investigation.” About half are presidential appointees requiring Senate confirmation but others are appointed by the head of their agencies.

And this may not be the end. The Daily Beast reported late last week that this may be “just the beginning of Trump’s plans to remake much of the federal government by appointing Trump-supportive partisans, including to inspector general posts, four administration sources say.”

Photograph of Glenn Fine by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.