The Democratic Party is often called the party of government. Ideologically, this is so obviously true it’s not worth belaboring. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. We have a federal government for a reason, and there are things it should do. Reasonable people can debate what those things are.

But there’s a difference between being the party of government in the ideological sense and being the party of government in the literal sense. A core constituency of the Democratic Party, both in terms of voters and donors, is people who work for the government.

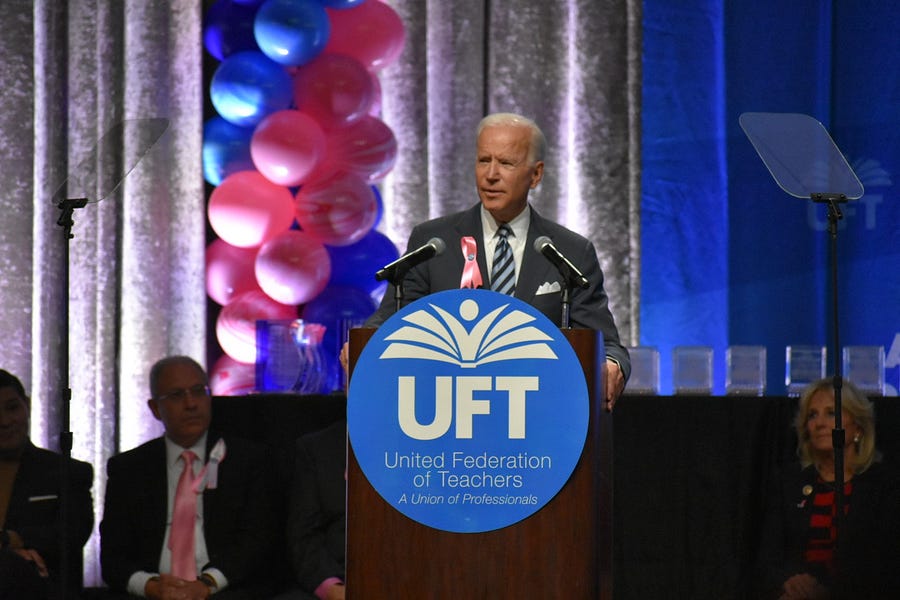

Members of teachers’ unions regularly constitute around 10 percent of delegates to Democratic Party conventions. There are about 3.5 million public school teachers in America, comprising about 1 percent of the U.S. population. That means teachers’ union members are overrepresented among the activist base of the Democratic Party by a factor of about 1,000 percent. In 2019-2020, according to Open Secrets, of the roughly $52 million that the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association spent on political donations, $130,000 went to Republicans or Republican groups, and the rest went to Democrats or Democratic groups—a ratio of about 400-to-1.

Of course, it’s not just teachers’ unions. In the 2020 election cycle alone, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) dedicated 99.1 percent of its political spending to Democrats. The American Federation of Government Employees gave 95.6 percent to Democrats.

At the state and local level, public-sector unions are often the biggest contributors to Democrats, not just in terms of money but also in terms of organizational effort.

No wonder that one of the first things Joe Biden did after being elected was issue an executive order repealing a Trump administration policy that restricted government employees from spending more than 25 percent of their time doing union business while on the job. It can now go back to 100 percent.

Of course, part of the Democratic Party’s preference for government unions can be explained by the central role organized labor has played in Democratic politics going back to at least the New Deal. In 2020, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, 90 percent of all labor spending on federal elections ($219 million) went to Democrats. Public-sector unions only comprised about a third of that ($68.5 million).

But there’s a difference between private-sector and public-sector unions. The former need a private sector to exist, which is why rank-and-file union members are less enthusiastic about Democrats than their unions’ political donations would suggest. Biden got only 57 percent of the union household vote. Leading up to the election, members of building trade unions were evenly split between Trump and Biden.

The difference between public-sector and private-sector unions isn’t trivial. Coal miners, factory workers, etc., formed unions in response to brutal working conditions, using their collective bargaining power to force important reforms from businesses. There is no similar history justifying public sector unions. There was no tragic Department of Motor Vehicles ceiling collapse that prompted government workers to organize.

Being pro-labor doesn’t require being pro-government labor union. Franklin D. Roosevelt, arguably the most pro-labor president in history, believed that “the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service.” George Meany, the first head of the AFL-CIO, held that it was “impossible to bargain collectively with the government.”

Sure, government workers deserve some basic protections, but civil service laws were already providing those when John F. Kennedy lifted the ban on government unions. If they were inadequate, politicians could have passed laws to boost them without creating a permanent constituency for more government and more government spending.

The crux of the problem is that government isn’t a business. It doesn’t have to run at a profit. It can keep borrowing (or printing) money almost indefinitely. Actual businesses need to keep the lights on by making a profit. That tension imposes discipline on both management and workers when it comes to private-sector unions. There is no similar countervailing pressure to keep labor costs in line or work rules efficient for government union labor. Since 1960, inflation-adjusted spending on education has increased by some 280 percent. Have we seen the quality of education improve 280 percent?

The party of government, and often government itself, is dominated by a constituency that, to put it charitably, has divided loyalties between what is good for the public and what is good for them.

Victor Gotbaum, a leader in the New York City chapter of AFSCME, summed up the problem in 1975 when he boasted, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.