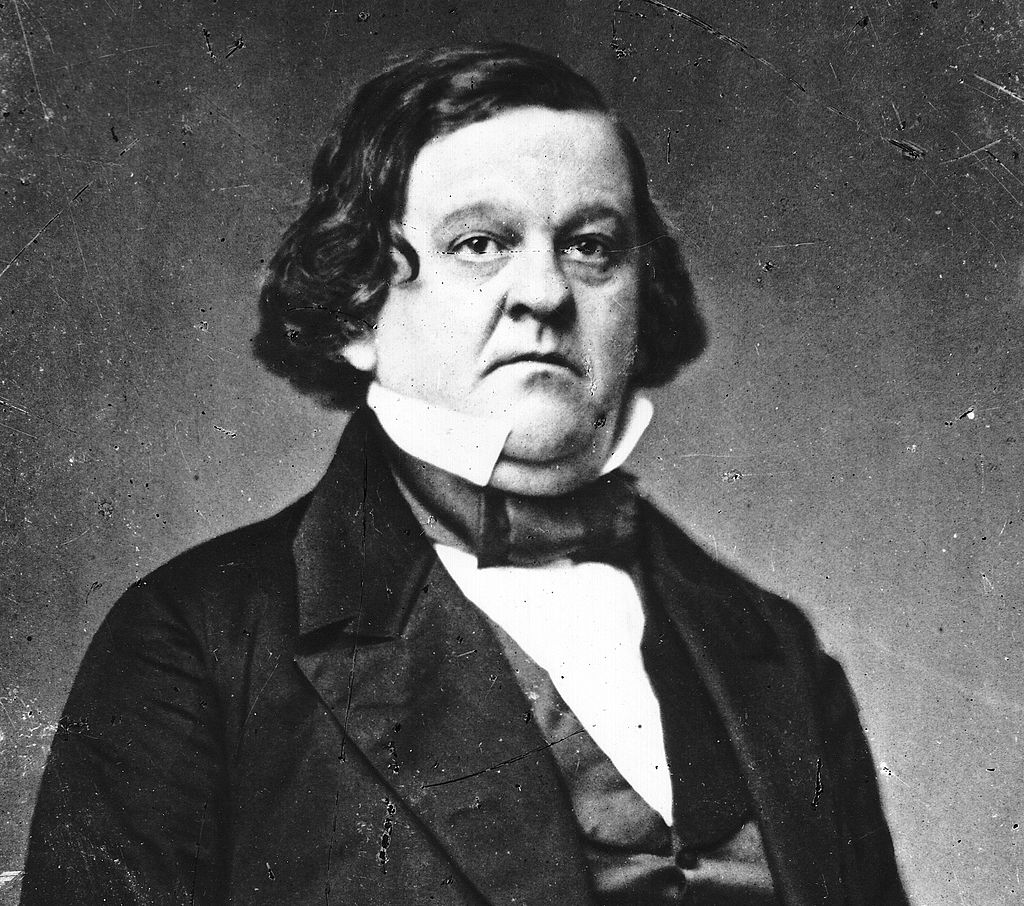

Howell Cobb had quite a résumé: speaker of the House, governor of Georgia, and secretary of the treasury.

He was also the author of a widely read and influential book, which he penned in between leaving the governor’s mansion and his return to Washington for his Cabinet post: A Scriptural Examination of the Institution of Slavery in the United States.

“African slavery is a punishment inflicted upon the enslaved, for their wickedness,” he wrote in 1856. “Slavery, as it exists in the United States, is the Providentially-arranged means whereby Africa is to be lifted from her deep degradation, to a state of civil and religious liberty.”

Yes, Secretary Cobb would not only go on to be one of the founding fathers of the Confederacy, he was one of the chief architects of the moral case for a rebellion to protect slavery. If anybody ever tells you that the principal cause of the Civil War and object of the Confederacy was something other than the perpetuation of human bondage, you can send them over to the works of one of its leading intellectual forces, and his authoritative judgments on how the Bible commanded Americans to keep slaves.

Cobb owed his prominent position in national Democratic politics in the 1850s to having been nearly as staunch a defender of the Union as he was of slavery. Nearly. Northern Democrats like Franklin Pierce, Stephen A. Douglas, and James Buchanan needed Southern support and to show their sympathies for perpetuating and expanding the “peculiar institution” even as the national attitude was turning increasingly hostile toward it.

But the real fanatics for slavery were moving toward secession and against the meager conciliations their fellow partisans in the North were offering, like the Fugitive Slave Act and the offer of expansion of slavery into Kansas. Cobb was perfect for those purposes: a red-hot racist who was also a man of great standing in the second-largest slave state and still a staunch supporter of union.

Those same attributes, though, made him a prized figure for the secessionists when he finally made the switch. They could say that even Howell Cobb—Cabinet secretary, political philosopher, unionist—had seen the necessity of rebellion. That made him the pick to be president of the Confederates’ constitutional convention. His job in founding the new nation was the same one George Washington had been given in Philadelphia 74 years before.

But rather than going into government after its founding, Cobb went into the field. Commissioned as a colonel, he saw plenty of action in the early years of the war before eventually rising to the rank of major general and in the fall of 1863 was given the command of CSA forces in Georgia and Florida. He got the job just in time for the arrival of Maj. Gen.William T. Sherman and his forces in North Georgia. Cobb could not stop Sherman’s drive to Atlanta, nor his march to the sea in the autumn of 1864.

Indeed, Sherman’s path from Atlanta to Savannah went straight through Baldwin County and Cobb’s great plantation. Sherman dined in the slave quarters there on the night of November 22, 1864. When he saw “a small box, like a candle-box, marked ‘Howell Cobb,’” whom Sherman knew to be “one of the leading rebels of the South” and from his time in the Buchanan administration, the Union general instructed his troops to confiscate all the crops, destroy the home, and to “spare nothing.”

“That night huge bonfires consumed the fence-rails, kept our soldiers warm,” Sherman recalled in his memoirs, “and the teamsters and men, as well as the slaves, carried off an immense quantity of corn and provisions of all sorts.”

But the greatest indignities were still ahead for Cobb.

In the early months of 1865, Sherman had turned north into the Carolinas while Ulysses Grant was bearing down on the Confederate capital of Richmond. For nearly a year, many in the officer corps had been asking for the army to begin enlisting slaves—for the manpower it would provide but also to help the Confederacy’s standing with the European powers unwilling to support the Southern cause because of the stigma of slavery.

The plan had been dismissed out of hand a year before, but with the Confederate army depleted and hundreds of thousands of free black soldiers by then fighting on the Union side, the matter got serious attention with Richmond in peril. Robert E. Lee supported the idea, suggesting that slaves should be offered their freedom after the war in exchange for enlistment. But not Howell Cobb.

Informed of the possibility, Cobb begged his superiors that slaves not be armed. He wrote to Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckenridge beseechingly: “The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

Cobb was at least right about that. The fine soldiering of free blacks for the United States had already proved Cobb wrong about his phony theological, pseudo-scientific babble. And the desperation of the crumbling Confederacy couldn’t afford to indulge it any longer.

On this day in 1865, the Confederate Army approved the enlistment and arming of black soldiers. The first black units were training in Richmond when the city fell three weeks later, the ultimate humiliation for Cobb and his fellows.

Cobb surrendered on April 20 in Macon, Georgia. His home, his career, his cause, and his much cherished dignity all destroyed for the love of the evil idea that God would ordain any of His children to be the master of another.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.