New Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney has firmly informed President Donald Trump, in the polite Canadian way, that his country is not for sale. If only someone had made that declaration on behalf of Canada’s original Major League Baseball team, the Montreal Expos.

Twenty years before Trump floated the idea of Canada becoming America’s 51st state, the Expos became America’s 29th baseball team, moving to Washington, D.C., to become the Nationals in 2005. That left the Toronto Blue Jays as the sport’s sole north-of-the-border outpost. In Trump’s dream world of wiping out what he calls the “artificially drawn line” separating the countries, Toronto would be a U.S. city and big-league baseball would once again be an all-American enterprise, as it had been until the birth of the Expos in 1969.

That’s how some members of Congress wanted the sport to remain when baseball’s National League announced in May 1968 that the league’s club owners had awarded Montreal an expansion franchise for the next season, along with San Diego. Those two cities beat out rival contenders Buffalo, New York; Milwaukee; and Dallas-Fort Worth. The decision to put a team in Canada provoked an angry America-first backlash from baseball boosters in the losing markets. (Also in 1969, the American League added two new teams: the Seattle Pilots and the Kansas City Royals.)

Ahead of the National League’s decision, Montreal had been given only an outside shot at landing a team, the New York Times reported.

“It is a shrine of ice hockey, but has had no high-level baseball since the Montreal Royals, a one-time International League farm team of the old Brooklyn Dodgers, were disbanded in 1960,” the Times noted. But the city made a strong bid with a promise for a domed stadium by 1971. As it turned out, the Expos wound up playing in tiny Jarry Park—its temporary home, which was known as Parc Jarry to the French-speaking population of Quebec—for eight seasons. It wasn’t until 1977 that the Expos finally moved into Olympic Stadium, after the facility hosted the 1976 Summer Olympics.

Montreal’s selection infuriated members of the House of Representatives from the three rejected U.S. markets, seven of whom wrote a letter to baseball Commissioner William Eckert protesting the NL’s decision to essentially build a company plant outside the United States.

“It seems to us that three of America’s major cities certainly merit teams before consideration is given to a franchise for a foreign city,” the six Democrats and one Republicans wrote, a half-century before Trump echoed that line of argument in urging companies to make their products in the U.S.

One of the signers, Texas Democratic Rep. Earle Cabell, said he would ask the House Judiciary Committee to look into “monopolistic practices among big-league owners”—a standard go-to for members of Congress when they’re angry at baseball and want to target the sport’s coveted antitrust exemption. (Cabell is mostly remembered today as the Dallas mayor who greeted President John F. Kennedy with a key to the city on the day he was assassinated in 1963.)

“For it is becoming all too evident that what was once our national game has now become the monopolistic province of a few profit-hungry, selfish men,” he said, according to an Associated Press report at the time.

Separately, a local judge in Milwaukee, Robert Cannon, who was part of that city’s bid, harrumphed, “It’s unthinkable that baseball would do this to cities in the United States – which made baseball what it is.”

Two of the three markets didn’t have to wait long for a major league team. In 1970, future Commissioner Bud Selig led a group that purchased the Pilots and moved them to Milwaukee to become the Brewers after one 98-loss season in Seattle. And following the ’71 season, the Washington Senators moved to Arlington, Texas—as the Washington Post’s Shirley Povich famously described it, “some jerk town with the single boast it is equidistant from Dallas and Fort Worth”—to become the Rangers.

Meanwhile, the Expos, typical of an expansion team, took a while to find their footing, starting out with 10 straight losing seasons. But by 1979, under manager Dick Williams, they started winning, with young stars such as Gary Carter and Andre Dawson, along with veterans Tony Pérez and Rusty Staub—a redhead whose French nickname was “Le Grand Orange.”

That season, they finished with a .594 winning percentage, second best in the league. In today’s expanded playoff era, that would have been enough to make the postseason, but back then, there were no wild cards and Montreal finished two games out of first place in the National League East.

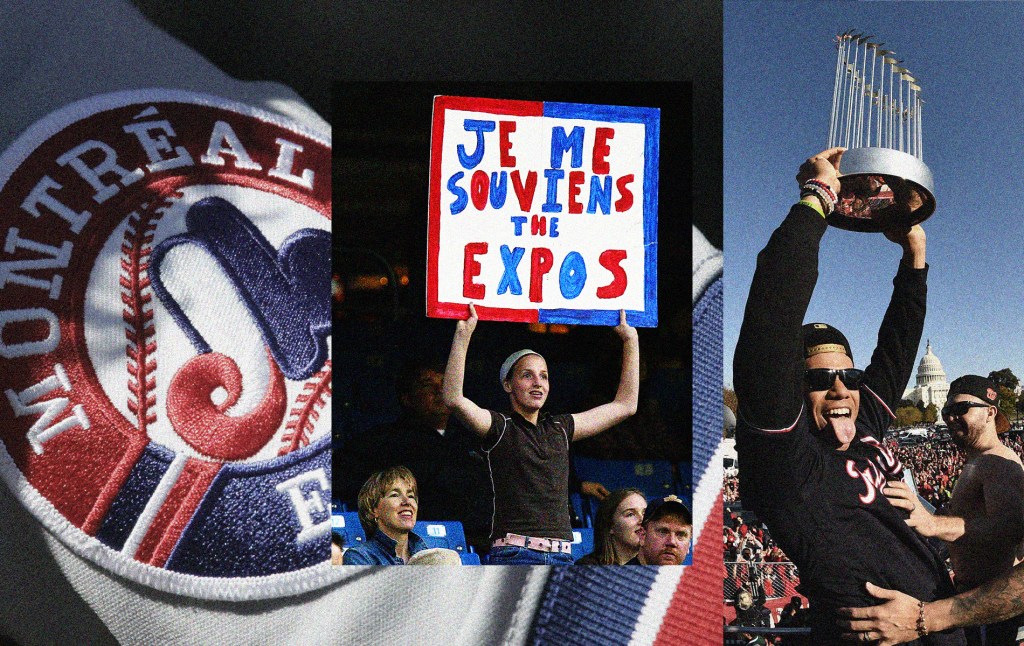

That near-miss seemed to epitomize the star-crossed franchise’s track record. The 1990s started out as a potential golden age of Canadian baseball, with the Blue Jays winning back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993. The next year, the Expos had the best record in baseball by August. The ’94 Expos featured a young Pedro Martinez in the starting rotation and star outfielders Moises Alou and Larry Walker. But the league’s players went on strike in mid-August; Major League Baseball wound up ending the season and canceling the World Series. The team never recovered. And Canada hasn’t won another World Series.

The national pastime, which helped crush the Expos’ championship dreams in 1994, tried to kill the team outright in 2001, following four straight seasons when Montreal finished last in the league in attendance—including averaging fewer than 8,000 fans a game in 2001. Major League Baseball had a plan to eliminate the franchise along with the Minnesota Twins, another team with low attendance and an obsolete stadium. But a court injunction forced the Twins to play in their Minneapolis ballpark the following season, causing MLB to abandon the plan, because eliminating just one franchise would have left the sport with an uneven number of teams.

The Expos were given a lifeline, but that lifeline didn’t save baseball in Montreal. In 2002, Expos owner Jeff Loria sold the team to MLB. As fan support dwindled, the Expos’ days in Montreal were numbered. In 2003 and 2004, they played some home games in Puerto Rico as a way to boost revenue for a team that continued to draw poorly in Montreal.

Meanwhile, after losing the Senators, Washington baseball boosters had tried for decades to get a new team. They came so close in 1974 to luring the Padres from San Diego that Topps printed a set of baseball cards of 15 Padres with “Washington Nat’l Lea.” printed on them. But that deal fell through, and after Peter Angelos bought the Baltimore Orioles in 1993, he helped block a team from the nation’s capital, concerned about losing fans in the region to a D.C. team.

However, when major league owners wanted to find a new home for the Expos, there weren’t good alternatives to Washington, so after the 2004 season, MLB announced it was relocating the team to D.C., which had gone 33 years without a team.

“This was a team that had to be moved,” Commissioner Selig said at the time. “We knew it had to relocate. Baseball didn’t want to own it anymore. This was a team owned by baseball that we were anxious to get rid of.”’

Ouch.

After the Expos’ 36 seasons in Canada, MLB had decided to “reshore” one of its teams to the U.S.—the kind of move that Trump would certainly approve of. Back then, Washington’s goals were modest, luring just a single baseball team across the border.

Today, some in Washington want to eliminate the border entirely.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.