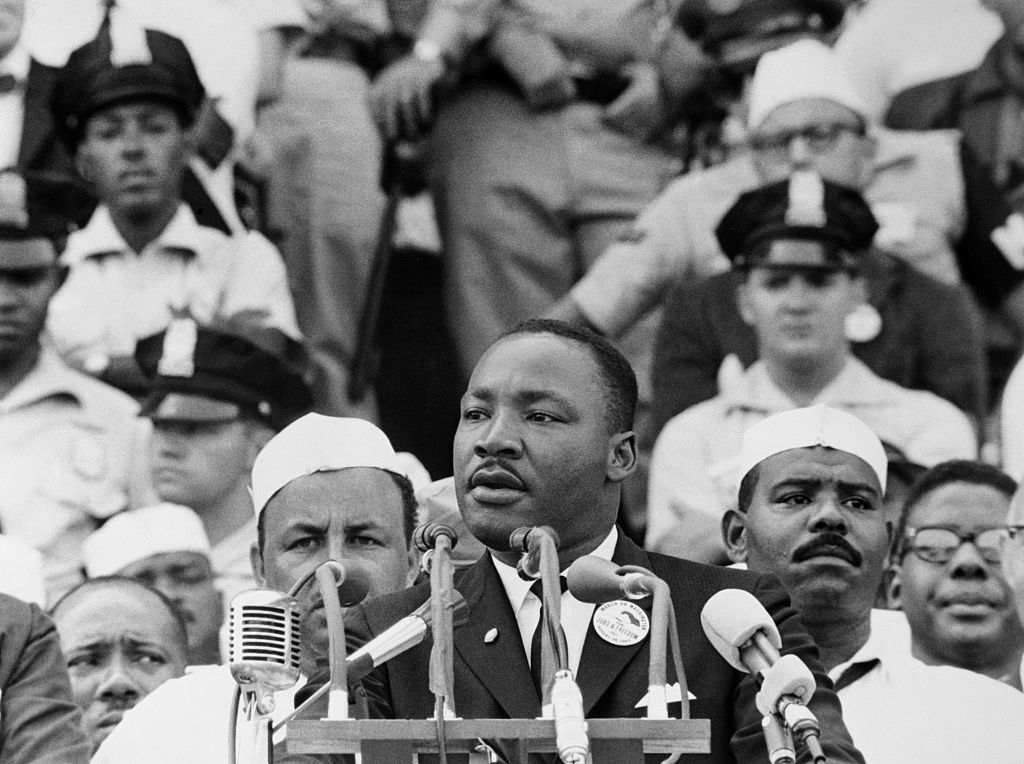

Despite his deep unpopularity with most white Americans while he was alive, today almost all Americans praise Martin Luther King Jr. as the hero of a badly needed civil rights movement. Conservatives included.

Those on the right especially seem to agree that the conservative resistance to King’s efforts stemmed from a racial animus now happily discarded. Whatever legal objections that stood in the way of approving the Civil Rights Act of 1964 seem trivial in retrospect. Even a politician like Barry Goldwater—pro-integration but constitutionally careful—publicly regretted his own scrupulosity in light of the terrors of Jim Crow. Yes, the fringes today are attempting to resurrect overt racism, but they’re largely seen as embarrassing dupes worth calling out. And attempts to dunk on King for his personal moral failings are greeted with a shrug. After all, conservatives have lots of heroes with much worse failings, and it’s usually us who argue—contra leftist iconoclasts—that one must take the good with the bad.

But the same cannot be said for King’s views on economic justice, which became increasingly radical in his later years. While his vision of racial harmony—or at least the bare outlines of it—has cross-partisan appeal, his interest in things like a universal basic income, union protections, and nationalized health care puts him at odds with free market conservatives. To be fair, it also put him at odds with his own father (who favored a full-throated capitalism) and with much of the black church tradition (which argued vehemently against the civil rights movement asking the government for economic support). King was no communist: Such a position was unthinkable in the black church, which roundly condemned the godlessness of communism. But he did call himself a socialist, and he refused to repudiate Marx entirely.

While conservatives might complain about this aspect of King’s thought, it’s worth reflecting on how it came about. Most conservative seminaries didn’t accept black applicants, for one, which meant that King ended up at Crozer Theological Seminary, known for its liberal theological leanings. Social redemption—the notion that God cares about both individual sin and social injustice—was already endemic in the black church. Not so with the “social gospel,” which emphasizes social redemption at the expense of orthodox commitments to Christ’s divinity and the resurrection of the dead. The black church has traditionally held high views of scripture and orthodox doctrine, and this was certainly true of King’s childhood upbringing. Famously, though, the white co-religionists most theologically similar were also least likely to support civil rights, while many theological progressives did. King could hardly be blamed for noticing that white Christians with more traditional theological views had so spiritualized their faith that they were able to justify turning a blind eye—or even actively participating in—serious social injustice.

It comes as no surprise that many black Americans in the 1960s were strongly in favor of major redistributive schemes (interestingly, that number has plummeted in recent years). If white conservatives arguing for free markets were unwilling to join in the fight to honor the full citizenship of black Americans, why take them seriously on economics? On the other hand, since white progressives were ready to march in solidarity, their emphasis on engineering our way out of poverty gained credibility.

However, these tendencies were highly controversial among black pioneers. That great warrior for black rights, Frederick Douglass, was a serious free marketeer (along with Garrison and his whole gaggle of abolitionists). He was even made an honorary Irishman—they called him the Black O’Connell—because his arguments for free trade meant cheap, affordable food for the poor. Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on property ownership and skills development built the National Negro Business League, whose greatest entrepreneurs (like Madam C.J. Walker) went on to fund NAACP chapters around the country. Langston Hughes blackballed the great novelist Zora Neale Hurston from the Harlem Renaissance because of her outspoken individualism, anti-communism, and hatred of FDR’s New Deal. And Joseph H. Jackson, the president of the National Baptist Convention, even wrote a book defending his organization’s commitment to the principles of equality under the law and black self help (in contrast to King’s radical economics).

And it’s important to recall that even back then, it wasn’t only black Americans or white progressives advocating for black rights. Two of the white co-founders of the NAACP were serious free marketeers: Oswald Garrison Villard and Moorfield Storey, who believed that a legal appeal to the Constitution could liberate black Americans from the horrors of Jim Crow.

Rose Wilder Lane, one of the three “mothers of libertarianism” (and daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder) wrote hundreds of columns for the greatest black newspaper of its day, The Pittsburgh Courier, under its conservative editor, “The Black H.L. Mencken,” George Schuyler. She argued against violence like lynching, but also against other forms of oppression—like zoning regulations—and in favor of individual rights being consistently applied to all. Milton Friedman was already raising the alarm about the effect of the minimum wage on black employment in the 1950s, calling it the “most anti-Negro law on the books.” His defense of school choice explicitly condemned its use as a form of segregation (and argued that, properly instituted, it would have the opposite effect).

These bits of history should remind free market conservatives that it’s always healthy to retain a strong dose of classical liberalism in your ranks. The conservative temperament is not naturally activist, which lends itself to too much lethargy about injustice—even when that injustice goes directly against one’s principled advocacy for private property and free exchange (as Jim Crow, red-lining, and urban renewal certainly did). They might also remind theological conservatives to turn inward and ask where one’s commitment to orthodoxy has veered into a gnostic, out-of-balance spiritualization of the Christian life.

More broadly, they should convince today’s conservatives to pause and take a breath between condemnations of the left to wonder why it has been able to suck all the air out of the room on racial questions. If you are not willing to step into the arena and offer your own solution, you can hardly complain that you lost the match.

Instead, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, free market conservatives ought to embrace the moral imagination required to demonstrate the efficacy of both the market and the right kinds of civil society efforts in helping the poor. The Institute for Justice does this when it defends low-income neighbors against taxation by citation, or when it fights for their right to open that barbershop or African hair-braiding business. My friends at the Illinois Policy Institute do this when they get food carts legalized in the city of Chicago. The folks at True Charity do this when they train nonprofits that support employment and entrepreneurship instead of dependence. Corey DeAngelis does this when he dedicates his life to the educational freedom favored by 70 percent of minority parents.

This MLK Day, let’s not just complain that King had the wrong ideas on economics. Let’s prove that we’ve got better ideas, but also the same heart.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.