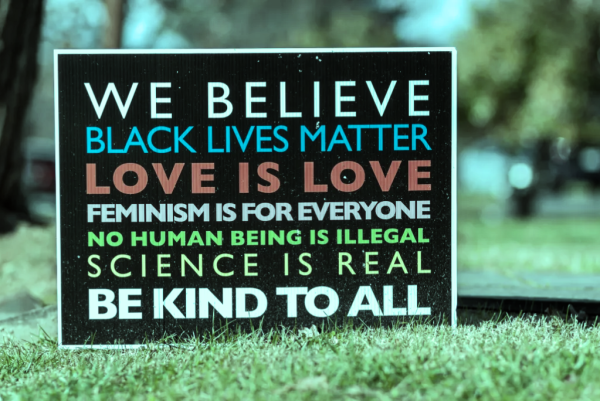

At the height of “wokeness” (or “social justice” if you like), writers like Helen Lewis and John McWhorter speculated that it might be “our new religion,” supplanting Christianity at a time when society was becoming increasingly secular. In a conversation about his book Woke Racism: How a New Religion Betrayed Black America, McWhorter described the “religion of wokeness” like this:

It’s an idea that there is an article of faith … That is what is important in this religion, that you acknowledge that you understand that to show that you’re a good person. … It’s policed in a way that really is reminiscent of the chasing away of heretics. … If you don’t agree with them, they think it’s okay to see that you lose your job … We’re dealing with a religion, and we have to know what we’re dealing with. That’s the point of the comparison.

For McWhorter, what stood out was the level of importance people placed on these beliefs. It was an act of faith to believe in the “woke” definition of being a good person so deeply you’d be willing to drive a member of your community out. But more specific examples—ones that transcended descriptions of cancel culture and the sadly familiar woke scapegoating—were also plentiful and compelling.

For example, George Floyd, the black man whose death ignited nationwide unrest in the summer of 2020, seemed to have been sanctified, with murals of his face prominently placed in almost every major American city. Politicians and celebrities regularly, and quite publicly, engaged in what seemed like ritual acts: Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer wearing Ghanaian kente cloths, people posting black squares on Instagram, or Gal Gadot enlisting her closest celebrity friends to sing John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Corporate America, accelerating beyond the stale diversity trainings and sexual harassment workshops that characterized ’90s and ‘00s “political correctness,” rushed headlong into the era of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Ordinary people confessed their privilege and internalized biases compulsively. Some still ended up “canceled,” while others fearfully retreated into self-imposed exile before the mob could cancel them first.

It was a strange (and possibly ongoing) cultural moment. Yet describing this phenomenon as a religion never felt entirely accurate.

There was no divine or supernatural element, for one. McWhorter might argue that not all religions need one, but it seems like a glaring blindspot. What, then, is the difference between a religion and any other belief system? While figures like George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, and—more recently, though to a much lesser extent—Jordan Neely took on a kind of mythic, folk-hero-like stature, they lacked truly religious character. People were not worshipful in the face of their stories, even if their fervor had a taste of the Pentecostal to it. In the end, George Floyd was a regular person—at most a martyr—who could just as easily have been you, me, or a neighbor, something you would never say of the pope, a saint, or Jesus Christ. There was no church and, as anyone who has been “canceled” could attest, no promise of redemption or transcendence.

But still, wokeness was touching on something deeply emotional. It was unfamiliar, at times frightening. It wasn’t “just politics.” There was, even if inarticulable, something undeniably new about it.

In a 2023 article published in The Atlantic, Tyler Austin Harper proposed that wokeness is not a religion so much as a New Age-inspired self-help grammar. Harper argued that the culture of “doing the work”—often expressed in corporate DEI initiatives—reflected a broader American obsession with ongoing personal improvement. He situated wokeness within a culture that prizes a never-ending process of “individualistic, corporatized anti-racism, one focused on the purification of white psyches through discomfort, guilt, and ‘doing the work’ as a road to self-improvement.” The connection he drew was more than just conceptual. Racial sensitivity training, Harper pointed out, has historical roots in the Human Potential Movement’s “encounter groups.” Many specific and distinct features of wokeness were born of New Age thought.

But while mostly persuasive, Harper’s explanation also feels like it’s missing something. There are many important differences between wokeness and any manner of New Age thinking. In fact, what annoys many woke people about New Age philosophy is how deeply libertarian it is.

It is “lift yourself up by the bootstraps” by another name, often with the addition of vague ideas like “energy” or bastardized interpretations of “qi” or “chakras.” If one were to write a single definition of the New Age ecosystem of thought—if such a summary is possible—it might be this: a loosely connected set of syncretic spiritual beliefs and practices that prioritize personal growth, sidestepping or outright ignoring the political. A New Age conference may offer a land acknowledgment at its start or ask for your desired pronouns, but the internal logic is decidedly “unwoke,” even “anti-woke.”

Wokeness, by contrast, insists that no amount of self-improvement can produce true justice. It demands self-improvement, but not only self-improvement. It wants sacrifice and looks for it hungrily. To cast wokeness as “self-help” might pick up on particular techniques—the sensitivity trainings or the self-examinations—but it downplays how wokeness often feels more like a reaction to New Age belief systems than an extension of them.

Wokeness does not believe that “reality is what you can get away with,” to echo the iconoclastic writer and “generalized agnostic” Robert Anton Wilson. It stands athwart the idea that anyone can succeed with the right mindset, an axiom that lies at the heart of New Age belief systems. Manifestation is downright insulting in the face of something as overbearing and insidious as “white supremacy.” You can’t just wishcast your way out of oppression—people must be removed, systems must be overturned, laws must be changed. Altering one’s language—Latino to Latinx, she to they, master bedroom to primary bedroom—is not a spell that grants us more equality in the woke mindset. It doesn’t make vulnerable populations less oppressed in the woke cosmology. It is simply the least one can do, a gatekeeping measure more than a religious exercise.

In fact, I would argue wokeness stands in stark contrast to what we might consider the narrating cosmology of the U.S. If there’s a faith that undergirds much of our culture, it’s the belief that our thoughts and wills can reshape our circumstances. We are a culture that believes we can “lift ourselves up by our bootstraps” in our heart of hearts. Even though the last 30-odd years have been overwrought with narratives of victimhood, this belief in being self-made, a conviction that personal effort and willpower can triumph over any and all adversity, rages on.

We see it in both benign, secular expressions (“believe in yourself”), and as well more emergent, mystical ones, which encourage tapping into “universal energy,” or “vibes” to reshape one’s reality. On the most esoteric side of the spectrum, there has been yearslong, widespread interest in “reality shifting” among young people on social media, a practice rooted in the idea that one can move their consciousness into alternate realities. In reality shifting, young people share techniques they believe can quite literally “transport their consciousness” to alternate timelines that align with their desires, whatever those desires may be. This, now somewhat famously, includes, but is not limited to, being a character in Bridgerton or Harry Potter.

Manifestation and prosperity gospel, two sides of the same coin, are instructive here as well, both built on the premise that focused intention—one urging you to “ask the universe,” the other to pray to God—can directly influence life in the physical world. We are a country that believes that you can quite literally “will” your way into anything from beauty to prosperity to marriage, implying that sheer mental resolve can help you achieve any goal. In many ways, that is the American Dream.

But the American Dream is fundamentally at odds with wokeness. Wokeness is preoccupied with systemic injustices, victims and oppressors. Changing your language and thus your mindset is only one part of wokeness’s proposed fix. The bigger-picture goal of wokeness is to simply change who is in power, from the so-called “white supremacists” to the “marginalized groups.” While there are many variations on the specifics of wokeness—some versions embrace capitalism, others lean more Marxist—it ultimately boils down to: The more marginalized people are in positions of power, the closer we will be to the goal of equality.

From one angle, then, wokeness can act as both a kind of filtering mechanism and a coping mechanism to the “lift yourself up by the bootstraps” mindset. It tells you why the American Dream isn’t working for you, specifically: It’s not that you didn’t work hard enough, it’s that you’re being stopped. You’re being oppressed. It’s the material that’s getting in the way. Wokeness explains what forces are preventing you from self-actualization. You may not become the God of your own world, because we do not live in a universe that supports a system where everyone who wants to can be a winner.

Wokeness is the great regulator that emerges near the breaking point of any system: academic departments facing resource shortages, media markets oversaturated with voices, or a worldview that assumes everyone can succeed with the right mindset. It says the system is rigged. It emerges directly as a critique of the American Dream to those who feel it’s not working and are not appealed to by other explanations—to name just one, regulations that impede the growth of new industries.

Or put another way: When our shared religion says “Yes,” wokeness retorts with an unbelieving “No.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.