From the start, Joe Biden’s presidency has existed in a sort of limbo. So will his speech on Monday night to the Democratic National Convention, fittingly.

Anxiety that he was too old to do the job has dogged him since he was inaugurated, when he immediately became the oldest president in U.S. history. As his behavior betrayed evidence of his decline, the anxiety deepened. Ask a group of voters today who’s really been running the country since 2021 and they’ll respond with a variety of names. And after the debate debacle of June 27, Biden’s might not be the most common.

He’s the president, but he isn’t. Limbo.

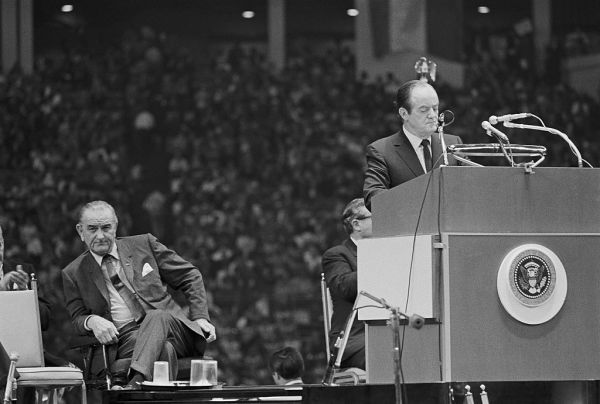

Tonight, he’ll address his party as an incumbent who’s eligible to run but has chosen not to. Not since Lyndon Johnson in 1968 has a sitting president declined to stand for reelection, and LBJ didn’t attend the convention that year. Biden’s speech will be unique in the modern era, in other words, as a spectacle of the leader of the nation willingly standing aside for a successor.

He’s the president, but he’s not the nominee. He’s the head of the executive branch and of the military, but not of his own party. Limbo.

The strange way in which Biden left the race has also created an emotional limbo for him and his party. To say that Biden ended his campaign “willingly” is technically true but functionally false. There was no “coup” in the form of a delegate revolt, and the president was free to fight on to the convention and to dare attendees there to deny him the prize he had won by sweeping this year’s primaries. But it was made clear to him privately that his party would go to war with him if he tried. And his own campaign’s polling of battleground states suggested that his reelection bid, like his physical health, was in irreversible decline.

So Biden’s withdrawal was voluntary, but it wasn’t. His pitch to America tonight to replace him with Kamala Harris will be heartfelt, but it won’t be. The hero’s welcome he receives from the audience will be sincere, but only because they’re glad to be rid of him. Limbo.

Night one of a four-day political pageant aimed at getting voters excited to support Democrats belongs to a man who was too unpopular, and ultimately too feeble, to win himself. How’s that for ambivalence?

Insofar as he’s both present and somehow not, simultaneously a memory and a figure capable of influencing events, Biden is the political equivalent of a ghost. But I don’t expect him to haunt this race as much as the last president in his position did.

The differences between Biden and Johnson.

Democrats face the same problem today as they did in 1968, having to win with a nominee who happens to be vice president in an administration so unpopular that the president himself opted not to run.

Biden’s job approval stands just north of 40 percent in the RealClearPolitics average. The last Gallup poll before LBJ quit the race in March of 1968 had him lower than that, at 36 percent. Johnson’s numbers improved briefly after he announced he wouldn’t run for reelection, but by late May he had settled back into the low 40s, where he would spend the rest of the campaign—an albatross for Humphrey because of his handling of the Vietnam war.

Yet Johnson had his uses. Kyle Longley’s fascinating history of the 1968 Democratic campaign on the homepage today notes that LBJ remained popular with important constituencies, like Southern “Blue Dog” Democrats, yet didn’t campaign in earnest with Humphrey until the final weeks of the race. Had he put aside his ego and reached out to those voters sooner, the outcome of what turned out to be a surprisingly tight election might have been different.

That’s one key distinction between Johnson and Biden. I’m not sure there are any modern voting blocs analogous to the Dixiecrats with whom our current president holds more sway than his replacement as nominee does.

Biden has traditionally been popular with black voters, for example, but he’d lost ground with working-class African Americans over the last few years. Harris appears to be reclaiming some of those votes: A Suffolk poll of Michigan and Pennsylvania finds her leading Donald Trump by 60 points or so among black voters in those states, significantly better than Biden’s recent leads of 40 to 45 points.

Older voters had also been a bright spot for Biden amid his polling downturn this year, but Harris is faring no worse than he did among them. A new Washington Post survey finds her polling at 47 percent with seniors, the same as the president did in July. Ditto for white voters, a secret ingredient in Biden’s 2020 victory over Trump. Harris is roughly matching him among white college graduates in the Post survey and has shaved a few points off of his deficit among working-class whites.

Overall, she’s earning 42 percent of the white vote. That’s 3 points better than the president managed last month.

Perhaps some of that will change as the campaign wears on, requiring Harris’ team to deploy Biden as a surrogate to reach reluctant demographics. (They’re no doubt watching her numbers with men carefully.) But right now, unlike Johnson, the president seems to be a burden to his party with no upsides.

On the other hand, he also seems to be less burdensome generally than LBJ was.

Longley describes the headaches Humphrey endured in having to somehow attract anti-war voters while defending Johnson’s Vietnam policy. In theory, Harris has the same problem, saddled with Biden’s baggage on inflation and immigration while she goes about trying to remake herself as a border hawk and an enemy of “price-gouging.”

But Harris has it easier than Humphrey did, I think, because of how perceptions of Biden’s age drive perceptions of his policies. My theory all along has been that voters tend to view the president’s failures as a function of his cognitive decline more so than a function of bad judgment driven by bad ideology. Because his enfeeblement looms so large in how the public thinks of him, everything they dislike about him tends to be filtered through it.

That wasn’t the case with Johnson, who was still a few months shy of turning 60 when he quit the race in 1968. The same goes for George W. Bush, who was 62 when his job approval dropped below 30 percent in late 2008 amid exasperation over his handling of Iraq and the financial crisis. Their respective successors as party nominees couldn’t blame those failures on some unique personal foible like advanced age.

Harris can, which explains why her fate in the polls has been so different from Humphrey’s. Humphrey trailed Richard Nixon by double digits when the convention was held that year, Longley notes, alarming some Democrats so much that they hoped Johnson might return as nominee. Harris has been an overnight sensation by comparison, turning a deficit of 3.1 points in national polling with Biden atop the ticket into a lead of 1.4 points and counting.

Per the Post, just 1 in 3 Americans believes Harris had a “great deal” or “good amount” of influence over the Biden administration’s economic policies, and fewer than 4 in 10 say the same about her influence over immigration policy—remarkably, given that she was the White House’s so-called “border czar.” She’s managed to offload the incumbent’s political baggage to a degree Hubert Humphrey could only have dreamed of, presumably because voters regard Biden’s baggage chiefly as a product of his age.

And that probably also explains why Biden, unlike Johnson and the “blue dogs,” no longer wields much influence over groups that have historically received him warmly. Opinions about the merits of LBJ’s Vietnam policy varied, but opinions about whether our current president is up to the job really don’t, especially now that Democrats are no longer electorally invested in his success. Which undecided constituency out there is waiting to be persuaded by a man who could barely get through a sentence in his debate with Trump?

It’s not a coincidence that Johnson didn’t speak at the 1968 convention and that Dubya hasn’t appeared at a Republican convention since leaving office, yet Joe Biden has been invited to speak on the first night in 2024 and can expect to be received with poignant affection. Because of his age, he doesn’t “own” his policy failures in the public imagination to the extent the other two did. He can be feted and even mourned as a man who received a bad break of sorts in office, losing his marbles before he was ready to go, rather than as a man who steered his party into a ditch through stupidity or hubris. He’s not hated the way a president who oversees an unpopular war is, I think. He’s pitied.

There’s one more way in which Johnson is meaningfully different from Biden. LBJ had a real chance to affect the outcome of the election by how he governed in the final months of his term. Biden probably will not.

Longley writes of Johnson’s efforts to broker a peace deal in Vietnam in the fall of 1968, an October surprise that might have drained anti-war resistance to Humphrey on the left and propelled him to victory. There’s nothing as momentous as that on Biden’s plate. The closest thing would be a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, but the left’s antipathy to Biden’s policy in Gaza doesn’t seem to be hurting Harris. Having the war drag on until fall might not cost her much.

Insofar as Biden is able to help his VP to victory, he’ll do so by averting crises that haven’t yet erupted rather than by ending ones that have already begun. A regional war between Israel and Iran or a Chinese blockade of Taiwan would have game-changing potential, especially if American troops end up in harm’s way. But for now, there’s little the president can do to solve the major problems bedeviling Harris: Inflation and a slowing economy are matters for the Federal Reserve, and it’s far too late to impress undecided voters with some perfunctory show of enforcement muscle at the border.

This is what it means to have a presidency in limbo. The most powerful man in the world somehow has no buttons of his own to push to help get his successor elected.

The good news for Kamala Harris is that, unlike in 1968, she has a deep presidential bench to call on to help fill the void left by the ghostly—and unpopular—Joe Biden.

Night of a thousand stars.

When Hubert Humphrey accepted the nomination, his party had controlled the presidency for all but eight of the previous 36 years. Yet there were no presidential alumni willing and able to help rally Democrats behind him.

Johnson was so disliked that he stayed away from the convention. Franklin Roosevelt had died decades earlier, John F. Kennedy a few years before. Harry Truman was well into his 80s, had left office with an approval rating in the low 30s, and represented an era that was culturally eons removed from the late 1960s. Humphrey had no one with national influence to help him remind partisan liberals, anti-war or not, of what had led them to become Democrats in the first place.

Harris has that in spades. The Clintons, the Obamas, and Jimmy Carter’s grandson Jason will all address the convention this week along with Joe Biden. And, weirdly to me, some people seem to think it’s a bad idea.

Granted, a roll call of Democratic presidents dating back almost 50 years does sit uneasily with Harris’ campaign theme, “We’re not going back.” And not every presidential alumnus will be received with unalloyed joy: After the failure of 2016 and the success of the MeToo movement, Bill and Hillary Clinton are an awkward display of Democratic royalty.

But here’s the thing about ex-presidents: They’re very popular. And I don’t just mean within their own parties.

Last year, Gallup asked Americans to assess the job performance of every president since the early 1970s. All but two had a rating of 57 percent or better, including Bush and Carter—each of whom had left office with a job approval in the low 30s. Clinton’s rating was 58 percent. Obama’s was 5 points higher than that.

Americans can’t help but love former presidents as they transition from partisan demons to quasi-nonpartisan elder statesmen. (Trump is an obvious exception.) Why wouldn’t Harris want to associate herself with that instead of with the highly unpopular president under whom she serves? “These are people who have gotten tens of millions of votes,” strategist Paul Begala told Politico of the Democrats’ night of a thousand presidential stars. “Not clicks, not Only Fans subscriptions. The holy grail of politics is capturing votes and winning and, while we love them, that’s why they’re on stage.”

Ex-presidents also help reassure voters who aren’t thrilled with the modern party’s direction that there’s still a place for them inside the tent.

Republican conventions in the Trump era are … different, as others have noted. In fact, Politico’s Jonathan Martin pointed out, not a single member of a former GOP presidential ticket addressed this year’s convention—including Trump’s own running mate from 2016 and 2020, who’s refused to endorse him. Some former nominees, like Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan, are treated as villains by the populist right to the same extent that Democrats like Obama are. I believe the only living Republican to appear on a national ballot who’s supporting Trump this year is Sarah Palin.

Purging the party of traditional conservatives suits Trump’s purposes of consolidating control over the right but at the cost of depriving Reaganites of a pretense to believe they’re still valued members of the GOP.

Democrats trotting out Clinton and Obama sends the opposite message to working-class voters who were alienated by “defund the police” and “trans women are women” progressivism and have been eyeing Trump this year. Many of them dislike Biden and leftist social engineering, but they’re comfortable with the “normal” Democrats of their youth, and Kamala Harris is quite keen to associate herself with normalcy in this election.

Remember, the right isn’t the only faction prone to nostalgia.

Most of all, though, ex-presidents remind voters of something half the country seems to have forgotten: Durable political success runs through effective parties, not through individual leaders.

Trump’s own staff understands that even if Trump himself does not. Martin points to a passage from Tim Alberta’s recent profile of the campaign in which top advisers Susie Wiles and Chris LaCivita conceded that they didn’t fear then-nominee Joe Biden but did fear “institutional Democrats.”

The Democratic Party, Wiles and LaCivita would tell me in conversations over the coming months, was a machine—well organized and well financed, with a record of support from the low-propensity voters who turn out every four years in presidential contests. Ordinarily, they explained, Democrats would have structural superiority in a race like this one. But something was holding the party back: Biden.

…

“I don’t think Joe Biden has a ton of advantages,” Wiles told me on Super Tuesday. “But I do think Democrats do.”

Politics is a team sport. Having glamorous, charismatic former leaders like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama appear onstage to support the new nominee communicates that members of the team—even ex-presidents—need to do right by their country by making sure the team succeeds.

Needless to say, that’s not the message conveyed by the ongoing hostage crisis that you and I know as the Republican Party. Had Trump lost this year’s primaries, he would have surely refused to endorse the candidate who had defeated him and encouraged his supporters to boycott the general election out of spite. His party demands loyalty to him, personally; the team without Trump is worth nothing.

Whereas, to Democrats, the team without the incumbent president as nominee is still worth everything.

Perhaps that’ll make tonight’s speech by the ghost of Joe Biden worth something to Harris after all. He might not draw the contrast explicitly but it’ll be there all the same: Had Trump found himself elbowed aside as nominee in mid-July to make way for a more electable nominee, he would have devoted the rest of his life to burning his party to the ground in rage. Biden, an ex-president who’s technically not quite “ex,” will try to boost his replacement up instead. He’s a team player in the end, reluctantly or not.

“The non-MAGA Republicans only wish they could pull off what their opposition did last month,” Martin wrote of the Democrats’ “coup” against the president. Only one party prioritizes victory over the feelings of its leader; it feels right somehow that Joe Biden, a party man through and through for more than 50 years, would offer himself publicly as a sacrifice this evening to demonstrate the point.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.