The prospect of a red wave washing away Democrats’ congressional majorities this fall is complicated for the average Dispatch reader, I’d imagine. It’s complicated for me. After two years, it’d be nice to have a legislative brake on the left’s worst excesses, not that the left’s worst excesses are always amenable to legislative braking.

But I don’t know that a new Republican House majority led by a wimp whose job security depends on placating an authoritarian cult is a net benefit to the United States. How do you feel, for instance, about Kevin McCarthy’s caucus destroying America’s creditworthiness just to prove that they’re ruthless and spiteful enough to do it?

If that’s too far-fetched, consider the probable fate of American military aid to Ukraine should a party beholden to Tucker Carlson’s fan base suddenly be granted a veto over it. Some MAGA populists are already considering it.

Wherever you land on the virtues and vices of divided government next year, it feels increasingly like we’re headed for that outcome. And I use the word “feels” advisedly, as not all experts are sold on the idea that the polls have moved meaningfully toward Republicans lately. If you want smart data-driven analysis of the midterm horse race, I encourage you to read Dispatch writers like Sarah Isgur and Chris Stirewalt.

But if you want to talk vibes, a blogger can handle that. The midterm vibes clearly have shifted in favor of the GOP in the last few weeks, whatever the polling might say. But why? After a summer in which everything seemed to go right for Democrats following a long stretch in which everything seemed to go wrong, the conventional wisdom has switched back to favoring Republicans in November. What explains it?

It starts with inflation.

Beginning in late June with the Dobbs decision overturning Roe and continuing into early September, Democrats ran off a series of unexpected political and policy wins. Multiple red states moved to ban abortion, galvanizing the pro-choice majority. Joe Manchin’s eleventh-hour reversal on a climate-change deal produced the Inflation Reduction Act. Gas prices fell day after day after day. Inflation slowed down, portending an outright reversal before fall and a “soft landing” for our strained economy. Biden took out the leader of al-Qaeda, a man who’d eluded us for more than 20 years.

And, oh right, the leader of the Republican Party had his home searched by federal agents because it turns out he’s been quietly hoarding state secrets. And then began making thinly veiled threats of mass violence if the Justice Department sought to hold him legally accountable for having done so.

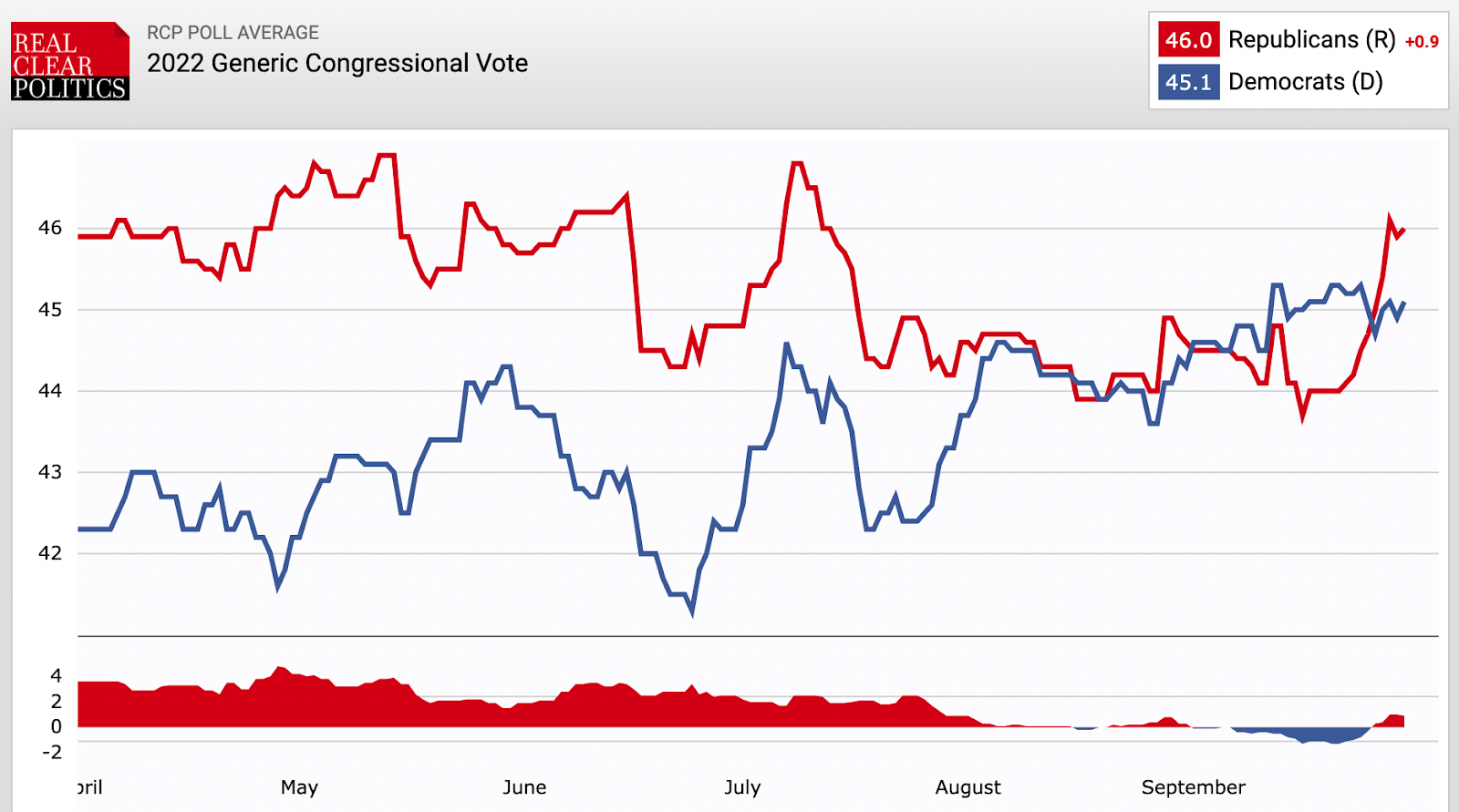

Democrats went from 41.3 percent in the RealClearPolitics generic-ballot average on the day Dobbs was decided in June to 44.6 percent and a slight lead over Republicans as of September 1. After falling to an eye-watering 36.8 percent job approval in late July, Biden recovered to a merely terrible 42 percent as September began, the political equivalent of Dems down ballot having to carry a 25-pound weight on their backs instead of a 100-pound one. For a brief moment it looked as though they might become narrow favorites to hold the House, an unthinkable turnabout given the headwinds they’d faced over the last year.

Then the new CPI report dropped. America had not, in fact, turned the corner on inflation. Democrats’ luck had run out. Within a week, the Fed was hiking interest rates by another 75 basis points and projecting a significant economic slowdown later this year or in 2023. It was tantamount to a patient who’d been feeling better discovering that their cancer was still spreading and more radiation would be needed to try to get it under control.

The vibes had shifted. Since the CPI report on September 13, the S&P 500 has lost more than 7 percent of its value.

Meanwhile, Republicans have wisely eased off on aggressive abortion restrictions so as not to spook swing voters. Most of the party is now engaged in strategic silence, the occasional tin-eared exception aside. Even brawling populists like Blake Masters are retconning their views on the subject. And it’s paying off: Nate Cohn noticed last week that Google searches about the economy overtook searches about abortion sometime in mid-August, an imperfect but provocative indicator of how voters’ priorities might be shifting.

As abortion was being replaced by the economy in the national debate, other topics more favorable to Republicans were also elbowing their way in. Some Ron DeSantis fanboys will tell you that his Martha’s Vineyard stunt was a political master stroke, not because it moved the needle on immigration but because it tilted the culture war away from Dobbs and toward Biden’s border policy. Biden himself introduced a volatile new issue into the cycle when he announced his student debt amnesty in late August, which some analysts herald as a brilliant ploy to energize young voters. But Trafalgar pollster Robert Cahaly told National Review recently that “he hasn’t seen any issue in a long time that motivates people as much as opposition to Biden’s student-loan forgiveness — ‘nothing touches it.’” And Cahaly has built a reputation for detecting conservative opinions that other pollsters overlook.

On Thursday, Biden’s administration quietly announced that a group of 4 million student debtors would be ineligible for his loan-forgiveness program after all despite earlier promises that they would qualify. Hmmmm.

Put all of it together and the vibe lately is that we’re headed back toward the sort of election we expected to have all along, a referendum on Biden’s first two years as president with an emphasis on the economy’s performance.

But there’s even more to it than that.

It’s possible that the vibe shift toward Democrats this summer was an illusion all along.

Not completely. The left’s record in special elections over the last few months, most notably the upset in NY-19, points to the Dobbs backlash being real, if overstated. What I mean is that the trend toward Dems may have been destined to hit a brick wall and reverse itself as we approached Election Day no matter what was happening in the news.

The best pithy explanation I’ve seen for how the conventional wisdom shifted toward Democrats and then rapidly back to Republicans comes from Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics.

That makes sense. The early-summer doldrums in Democratic polling were likely due to disaffected progressives peeling off in frustration that their party had failed to reach a deal on Build Back Better after a year of trying. Then Joe Manchin pulled a rabbit out of his hat to give them something on climate change and suddenly they were believers in the virtues of Democratic government again. The end of Roe around the same time gave them another powerful reason to shed their tedious belief that there are no meaningful differences between the parties. Progressives and liberals were back onside, boosting the numbers for their party and their president and creating temporary parity with the GOP.

But you know how it goes in midterms. The out-party typically carries the day, not just because their voters are hungrier but because independents have spent two years stewing over their frustrations with the ruling party. It’s rare for the president’s party to do well in House races in a midterm, but do you have any idea how rare? More from Trende:

The president’s party has managed to avoid losses in excess of four seats, five times since 1882 (before 1882 we did not have a single Election Day, or even Election Year, for Congress). One of those times, 1902, was an election that involved an increase in the size of the House; the president’s party lost ground in terms of its share of the House. So, out of the 34 midterm elections dating back to 1882, four have involved a president’s party losing fewer than five seats. That’s about 12% of the elections, which seems a reasonable starting point for expectations.

Does this year look like any of those elections? In 1934, the country was enjoying sharp economic growth in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first term. In 1962, the country was in an economic boom, and the incumbent president had a job approval rating of around 70%. In 1998, the country was again enjoying strong growth, and the president had a job approval of around 65% on Election Day. In 2002 growth was mediocre, but George W. Bush’s job approval was still stratospheric in the wake of the 9/11 attacks; Republicans also enjoyed a relatively favorable redistricting year.

Joe Biden was sitting at 42.6 percent approval in the RCP average on Friday while economists turn ever grimmer about the odds of escaping this spell of inflation without serious economic pain. Per Trende’s history lesson, does that sound like a national environment in which we’d expect the ruling party to beat midterm expectations considerably?

No one should underestimate the possibility of a significant Dobbs backlash goosing turnout on the left in November and no one does after the shocking result in Kansas’s referendum this summer. But the so-called “fundamentals” remain so poor for Democrats, and their current margin in the House is so narrow, that it’s almost inconceivable that they’ll hold onto the chamber. Major improvement on inflation in the CPI report this month might have upended those expectations by forcing voters to reassess their sense of the fundamentals, producing a more optimistic electorate this fall than any of us foresaw.

But there was no major improvement, and now the vibes about stubborn inflation and a deteriorating economy seem set in stone. Good luck to any ruling party in an election where the public is darkly pessimistic about the future.

There’s another element contributing to the recent vibe shift and this one does have to do with polling.

Here’s the generic ballot average at RCP as of Friday. The data has caught up to the vibes.

After trailing by more than a point in mid-September, Republicans are back on top. And it’s not just because of inflation.

Scroll through the list of polls collected at RCP and you’ll see that it’s hard to find a poll of likely voters that shows Democrats ahead. Of the 45 polls published since August, only two—two—have Dems leading among a sample of likely voters. And coincidentally, those two happen to have the smallest samples in the bunch, which means they also have the highest margins of error.

There’s virtually no evidence that Democrats are ahead among the people who count, the ones who plan to actually get off their couches this fall and vote. Pollsters across the board are expecting a very red electorate. To take one example, a recent ABC/WaPo poll found Republicans narrowly ahead among registered voters, 47-46, but comfortably ahead among likely voters, 51-46. Some 81 percent of Republicans said they were “absolutely certain” to vote compared to 75 percent of Democrats; per Nate Cohn, those numbers were similar in a contemporaneous CBS poll, where the split was 79-74. By no means is it a sure thing that liberals will turn out en masse to express their anger over Roe.

If that enthusiasm gap continues to hold across polling then we should see the GOP’s generic-ballot lead continue to rise for the simple reason that more pollsters will be switching from “screens” of registered voters to likely voters as we approach Election Day.

And then of course there are the late-deciders, the independents who don’t lean strongly toward either party but tend to make up their minds at the last minute. Conceivably they’ll be swayed by abortion politics into voting Democratic this year. But between the country refocusing on the dismal economy and the fact that independents historically break against the president’s party in midterms, that’s further reason to believe that the GOP’s margins in House races will continue to expand rather than contract.

Even Nate Silver, who challenged the idea of a vibe shift toward Republicans in a piece in mid-September, has begun to come around. On Friday he published an update allowing that “[t]he case for a GOP rebound is a little better.” How could he not? Look at the trends in the Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin Senate races, for starters. The strong updraft from the “fundamentals” seems more and more likely to boost Republicans to victory in tight races despite the downdraft from poor candidate selection.

There’s a tantalizing mystery at the heart of all this. Could the vibe shift toward Republicans be even greater than the polls perceive?

Or, rather, could Republicans have had a stranglehold on the midterms all year such that there never really was a vibe shift toward Democrats this summer?

The polls needn’t be wrong for that to be true. Consider this staggering result from the ABC/WaPo poll I mentioned above.

Among those living in congressional districts that are rated as at least somewhat competitive by ABC’s FiveThirtyEight (neither solid Republican nor solid Democratic), registered voters favor Republican candidates by a wide 55-34 percent – nearly as big as the Republican lead in solid GOP districts (+24 points). Democrats lead by 35 points in solid Democratic districts, pointing to a potential overvote where they’re most prevalent.

Polling of the national generic ballot is only so useful in deciphering how 435 distinct districts will break. We could see Democrats score Saddam Hussein margins of victory in indigo districts due to a left-wing Dobbs backlash and then fall short in one battleground after another as voters frustrated with inflation overwhelm the ardent but much smaller pro-choice contingent.

And since we’re vibing here, if you want the best of the best-case scenarios for the Republican Party, I recommend this Cohn piece on systemic polling error from last month if you missed it at the time. In theory, the polls this year might be systematically underestimating either party by overlooking an important contingent of voters when modeling the electorate. For instance, there could be a large group of casual young voters incensed at Dobbs who tend not to respond to polling surveys but fully intend to vote this fall. The polls would miss them, and therefore underestimate Democratic support.

But if you’ve followed elections during the Trump era, you know that’s not how it tends to go—at least when Trump is on the ballot. It’s Republicans, not Democrats, who tend to be lowballed in polling, probably because some meaningful number of MAGA voters has decided on principle not to answer the phone when some “fake news” liberal establishment pollster dials them up. The resulting oversight produced some garish discrepancies in 2020 between the polling and the results on Election Day, especially in states like Maine and South Carolina where Republicans who were cracked up to be in tight races ended up waltzing to victory. Cohn wonders whether history might be repeating this year. Other analysts are wondering the same thing.

If it happens again, America’s polling industry will have proved itself to be little better than, well, vibes. Bad news for writers. Great news for bloggers!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.