We owe a little praise to the governor of Iowa, who did something on Monday that’s unusual in Republican politics. She put the interests of her party and her country ahead of her professional ambition.

Sort of.

I won’t break my arm patting Kim Reynolds on the back for endorsing an underwhelming authoritarian for president over a more charismatic one. If doing right by the GOP and America was her priority, she would have backed the recognizably liberal Nikki Haley instead of a post-liberal who’s running as “Trump, but more aggressive.”

But I’ll pat her on the back for declining to endorse the frontrunner despite the fact that he’s 30 points up in her state and will now bear her a grudge that’ll make her life unpleasant in all sorts of ways.

For instance, the senior senator in Reynolds’ home state is 90 years old. His seat could become vacant at any time. A week ago, a governor as popular in her party as she is would have been a favorite to succeed him. No more. She just earned herself a vigorous Trump-backed primary challenge in her next election.

She also chose to endorse Ron DeSantis at a moment when he’s never looked weaker and Trump has never looked stronger.

DeSantis’ polling in Iowa is the same today in the RealClearPolitics average as it was at the end of July. Haley is the candidate who’s on the move, tripling her share of the vote over the same period. Prominent Republicans in DeSantis’ home state have lately begun abandoning him for Trump. And if he performs badly at Wednesday’s third presidential primary debate, Reynolds will look like a chump for having gone all-in on him.

In two weeks, DeSantis could be in third place in Iowa, making Reynolds’ pretensions of influence in her home state a subject of ridicule.

She bet a considerable amount of her political capital on the proposition that DeSantis will at last land on a strategy that turns things around after six months of failing miserably. That bet almost certainly won’t pay off, and Reynolds knows it. She didn’t place it because it was a smart political play. She placed it, surely, because she believes in DeSantis’ candidacy and craves change at the top of the party.

She was willing to risk something to try to loosen Trump’s grip on the American right. She deserves our thanks for that act of leadership. I bet the death threats are already rolling in.

But let’s not praise her too much. Reynolds’ endorsement can be understood in terms of ambition: She had little chance of being chosen as Trump’s running mate but now tops the short list to be DeSantis’. Backing him is a high-risk, high-reward gamble for a governor eyeing national stature.

And let’s not overlook the curious rationale she gave for her endorsement. When asked in an interview with NBC News why she preferred DeSantis to the frontrunner, she made a claim that grows less persuasive even as it grows more familiar. “I believe he can’t win,” she said of Trump, “and I believe that Ron can. And that’s a big reason I got behind him.”

As George Will might say: Well.

If you haven’t followed DeSantis’ campaign of late (and why would you, given the polling?), you might be surprised to learn that he’s gotten more confrontational with Trump.

For months, his detractors complained that he needed to go strongly negative on the man in the lead to have a hope of catching him. Sly, nameless allusions to candidates who were “focused on the past” were too cute by half. “Vague platitudes about ‘fresh leadership’ and ‘someone who can win’ have not yet been paired with an effective explanation of why Mr. Trump is neither of those things, and as a result Republican voters don’t believe either is true,” pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson wrote in an op-ed published Tuesday.

With Iowa set to vote in just two months or so, DeSantis’ desperation to gain traction has made him punchier. On Monday, his campaign’s rapid response team unfurled a series of video clips of “every one of Donald Trump’s fumbles, accidents, and confused moments from this year,” promising to make it a “running list.” Joe Biden isn’t the only candidate whose senescence is now a live issue in a presidential primary.

A few days ago, after Team Trump mocked DeSantis for allegedly wearing lifts in his boots, the governor responded by questioning his opponent’s manhood in unusually blunt terms.

The line was triggering to those of us who remember the brief period of the 2016 primary when the candidates began comparing their hand sizes, but if you found DeSantis to be too soft on Trump before, watching him scoff publicly at the size of his cojones was encouraging. In a way.

On Monday, during a joint NBC News interview with Reynolds, the Florida governor couldn’t contain his scorn when observing how shallow Trump’s political calculus is.

I’m skeptical that that point will weigh heavily on Republican primary voters, considering their own political calculus frequently boils down to “nice to Trump” versus “mean to Trump.” But it can’t hurt to remind them, I suppose, in case there’s still a modicum of shame somewhere in the right’s body politic.

All in all, DeSantis appears ready to go for broke in his criticisms—almost. But not quite.

There’s still one Trump weakness he dares not exploit. When Sean Hannity asked him during an interview on Monday why he believed Trump’s polling has gone up since he was indicted, DeSantis sounded almost almost sympathetic to his opponent:

“I think when that Alvin Bragg case came down [in Manhattan], it was just so transparently ridiculous. And to go back seven or eight years [in terms of the charges], clearly this would not have been brought for nonpolitical reasons. And so I think that he got a lot of sympathy, you know, as a result of that, in particular, maybe some of the others, too,” he said.

“But I think that one really just showed how ridiculous, quite frankly, the justice system has become when it’s in the hands of leftist politicians and leftist activists.”

It’s true that the Bragg case is the weakest of the indictments Trump is facing. But it’s also plainly true by now that there will never come a point in this campaign where Trump’s opponents are willing to challenge his moral fitness for office.

And by “moral fitness,” I don’t just mean the criminal charges that are pending. I mean all of it—the indictments, the coup plot, the unsubtle designs on consolidating power over the military and law enforcement and applying it to his own vindictive ends.

There’s never been a presidential candidate with a following the size of Trump’s who’s been as nakedly autocratic in his ambitions. Next year, tens of millions of voters, myself included, will consider it the only relevant issue when deciding how to vote. Yet the subject is bizarrely forbidden in the Republican presidential primary; even Haley, the “liberal” among the top three, won’t touch it. DeSantis is on the cusp of becoming an afterthought in the race, with little to lose, and he still won’t acknowledge the elephant in the room.

Others have noted how there are essentially two Republican primaries playing out in parallel: the actual one, in which Trump is waltzing to the nomination, and the fantasy one imagined by the donor class in which DeSantis or Haley might catch and overtake him. I’d add that there are two general elections playing out as well. One is an old-fashioned “which candidate would be better for the economy?” contest between two plausible candidates; the other is a “we cannot put this fascist lunatic back in power” referendum on you-know-who. To listen to Trump’s most formidable Republican opponents on the trail, you’d have no idea that that second electorate exists.

They can’t speak to that electorate because questioning Trump’s fitness for office has become a moral litmus test in its own right among most Republican voters. It’s a product of the feedback loop created by the personality cult he’s built around himself. As “disloyal” right-wingers have been purged or drifted away from the party, the Republican consensus about Trump’s fitness has calcified into dogma. To challenge his fitness at this point is to declare yourself not of the right, and therefore dead on arrival in a GOP primary.

We’ll never see a more absurd illustration of it than this soundbite from Peter Meijer, the former GOP congressman who is now running for U.S. Senate in Michigan.

Meijer was prepared to remove Trump from office two years ago for his behavior leading up to—and on—January 6. Today, to have even a remote chance of winning a Republican Senate primary, he’s obliged to argue that the coup-plotter whom he hoped to oust should be returned to the same office from which he hoped to oust him. It’s preposterous. But any other position would render him unviable.

Which brings us back to Kim Reynolds.

The recurring conundrum for prominent Republicans is how to persuade the party’s voters not to support Trump when the most compelling argument against him—his fitness—is the one those voters simply won’t stand for.

Politicians like to speak of “permission structures.” Voters are tribal and won’t easily abandon their tribal beliefs; the art of political persuasion is to convince them that they have “permission” from some important authority to do so. Trump is a master of that art by virtue of the cult dynamic he’s created. Once he became the locus of political authority on the right and offered de facto permission for fans to change their beliefs to suit his, the small-government credo of the Tea Party era—and even classical liberalism itself—became entirely negotiable.

Kim Reynolds is creating a permission structure for populists to switch from Trump to DeSantis. But she can’t appeal to their sense of morality, as they’ve outsourced that to Trump in matters of politics. (Also, extolling the virtue of classical liberalism while making the case for Ron DeSantis would be, uh, weird.) Republican voters have created their own permission structure of sorts in deciding which criticisms of Trump they will and won’t tolerate from their leaders, and they won’t tolerate Reynolds or anyone else attacking his fitness.

That’s why so many criticisms of him tend to steer around to electability. Questioning his character or his autocratic aspirations isn’t permitted, but worrying that his character or autocratic aspirations might impede the right’s quest for power is acceptable. (In theory. In practice, the Associated Press has already heard grumbling among Republicans in Iowa about Reynolds’ “disloyalty” by not remaining neutral in the primary.) Misgivings about him must be framed as concerns about the welfare of the tribe, never on their own moral merits, if you aim to retain your status as a member in good standing.

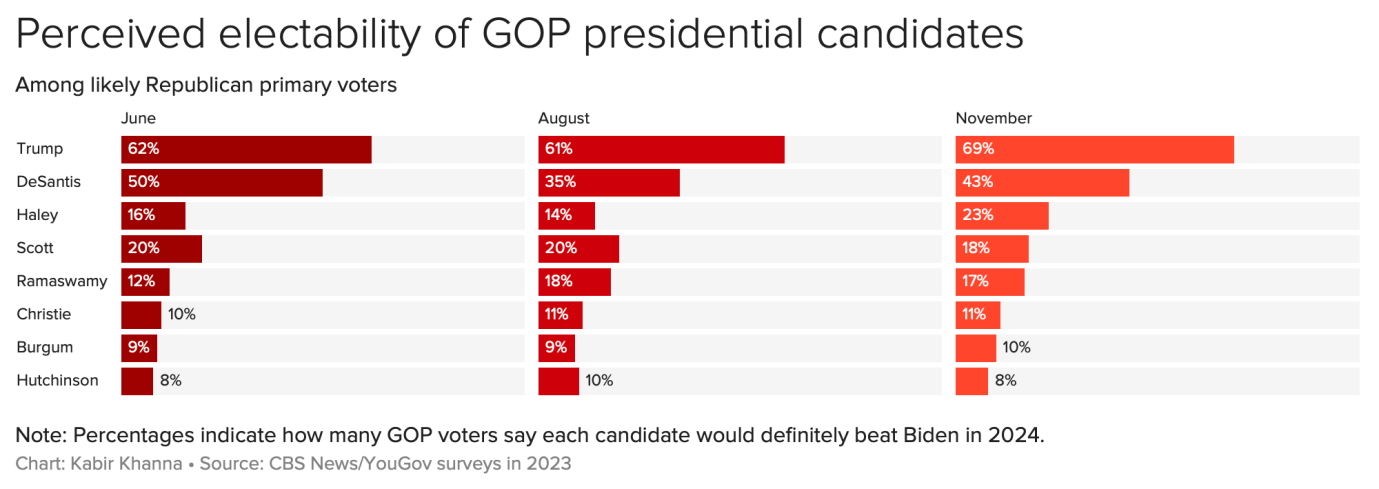

What makes this unusually absurd in Reynolds’ case is that “electability” has never been less of a liability for Trump than it is right now. In fact, if she were earnestly interested in nominating the candidate with the best chance of becoming president next fall, Ron DeSantis is arguably third on the Republican depth chart.

I won’t rehash the strength of Trump’s polling lately since we covered that yesterday. It should suffice to say that he continues to lead Biden head-to-head in the RealClearPolitics average while DeSantis trails slightly. Perhaps that would change once DeSantis clinched the nomination and pivoted to the center for the general election. Or perhaps not: By trying to outflank Trump on the right, the governor may have irreparably alienated MAGA diehards and center-right voters who were intrigued by him early in the campaign.

It’s Haley who’s become the “electability candidate.” In a recent national survey by Echelon Insights, Trump and DeSantis were each statistically tied with Biden in a hypothetical matchup while Haley led the president by 5 points. In the New York Times poll of battleground states that made waves on Sunday, Haley was comfortably ahead of the president in all six states—and outperformed Trump head-to-head against Biden in four of the six.

Of the three Republican candidates, DeSantis performed worst against Biden. In five of six states, Trump polled better against the president than the governor of Florida did. Haley polled better against Biden than DeSantis did in all six.

The caveats to that data are obvious. DeSantis has been pummeled by Trump all year long while Haley has gotten off nearly scot-free. If and when the frontrunner ever lets loose on her, her polling against Biden will suffer too. And it’s an open question whether MAGA populists would support Haley in a general election against Biden, even on “lesser of two evils” grounds. DeSantis, the post-liberal, would be a more highly valued consolation prize for them than a traditional conservative would be.

But even if Reynolds managed to convince Republicans that her candidate is more electable than Nikki Haley, she’d still run headfirst into this problem:

Republican voters just don’t buy that Trump can’t win. And why should they? All available evidence suggests that he can. He’ll turn off centrist voters who might otherwise support DeSantis or Haley in a general election, but he’ll also turn out voters whom neither of them would reach. Reynolds has been forced into an absurd, transparently false argument about Trump’s alleged unelectability because she doesn’t have moral permission from her party to make the argument that’s transparently true—namely, he’s a civic cancer who hopes to run America like a banana republic.

I wonder how much we’ll end up paying for this dishonesty.

Tuesday brought news of the latest error by Joe Biden’s political team. “The president’s team made a calculation earlier this year to prioritize bolstering Biden’s image versus attacking Trump’s in paid advertising, according to White House aides, a number of Democratic strategists and a top Biden campaign donor,” Politico reported. “Among the reasons: They figured the ex-president’s GOP primary rivals would do much of the work of roughing him up for them.”

To be fair, that’s normally how contested primaries work. The frontrunner gets his nose bloodied by ambitious rivals eager to make the strongest available arguments against him and those arguments end up weakening him in the general election.

Not this time. Team Biden forgot that the priorities of modern Republican primary voters are far out of whack with the priorities of general election swing voters, so much so that attacks that would wound Trump among the latter might actually help him among the former. “He’ll plunge the country into one constitutional crisis after another as he goes about wrecking civic institutions” is the sort of thing a Republican is expected to say with a smile on his face, as praise for Trump, not as criticism.

So Biden and his party will need to carry the full weight of making the moral case against Trump. The Republican establishment won’t help by demanding that the right reckon honestly with the potential consequences of the former president’s authoritarian schemes—not even members of the establishment like DeSantis and Haley who, conceivably, stand to benefit from that reckoning.

The irony of all this is that Kim Reynolds and other governors who should know better are ultimately creating another kind of permission structure by framing their objections to Trump in terms of electability rather than morals. What they’re doing—maybe deliberately, maybe not—is granting permission to Republican voters who do have qualms about what Trump might do in a second term to vote for him again next year. “He can’t win” isn’t an argument to oppose him, after all; it’s an empirical claim that’s easily falsified by polling data. “He shouldn’t win and here’s why” is an argument to oppose him.

But neither Reynolds nor DeSantis nor even pro-impeachment Peter Meijer will make that argument forthrightly. Maybe they really do prefer a second Trump term to a second Biden term, with all that portends, or maybe they can’t bear to defy the permission structure created for them by Republican voters that limits the ways they can safely criticize Trump. But I can’t believe that any of them seriously think Trump can’t win—or that repeating that falsehood ad nauseam like an incantation will finally puncture the collective right-wing consciousness and cause a stampede toward some alternative.

Tim Miller of The Bulwark recently wrote about an exchange he had with anti-Trump conservative Michael Wood, a former House candidate in Texas. “There is only so much tap dancing you can do on MAGA and Trump,” Wood told him. “It’s either the full Liz [Cheney] or the full Newsmax and everyone has to choose eventually.” By arguing disingenuously that Trump can’t win in lieu of arguing righteously that he shouldn’t, Reynolds is tap-dancing in order to postpone having to make that choice. But when the time comes for her to choose next year, I’m confident which side she’ll choose. Neither you nor I will like it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.