Welcome to Boiling Frogs. Some programming notes: Readers who want to receive this newsletter by email will be able to sign up to do so once we launch our new website in a couple of weeks. For now, we’ll be posting the items online, accessible to everyone. But after a trial period, most posts will be for members only. If you’re not already a member, now is a great time to join: We’re offering $20 off annual memberships. That’s an especially good value when you consider that there will be Boiling Frogs content nearly every day. We hope you enjoy this first installment.

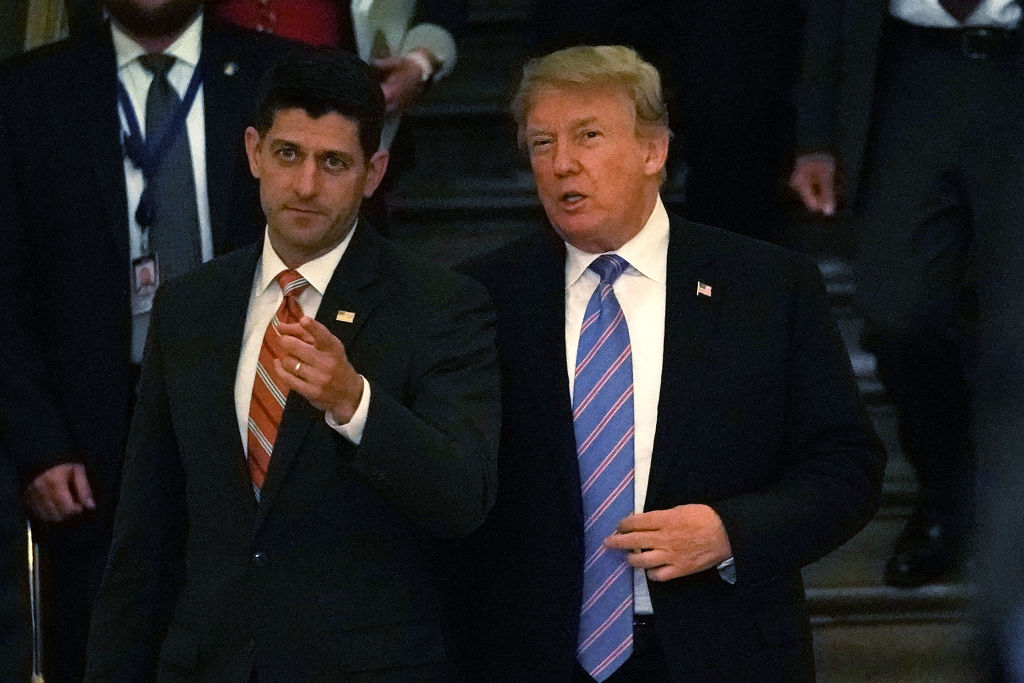

One of the more illuminating footnotes of the Trump years comes from an interview Paul Ryan gave in 2018. Ryan was on his way out of Washington by then, an ember of post-Reagan Republicanism smothered by Trumpism and finally flickering out. He told the New York Times that Trump had privately taken to calling him a “Boy Scout,” a habit that began at their first meeting after the 2016 election. But one day, after Ryan’s House majority had pushed through a number of bills on the president’s agenda, a pleased Trump informed him that he would no longer use the term.

“I guess he meant it as an insult all along,” Ryan later observed. “I didn’t realize.”

This newsletter will cover many subjects but it will concern itself foremost with politics in a populist age. And to understand the divide on the American right between populists and the rest of us, you first need to wrestle with this question: Are Boy Scouts chumps?

Boy Scouts are taught to behave honorably. Are they well-served by that training or does it condition them to fail as adults by encouraging them to eschew opportunities that people of lesser character would seize?

Is honor just an excuse weaklings make for weakness, masquerading their timidity as gallantry?

Ask a Dispatch reader to name an honorable politician and most would say Liz Cheney. Cheney has devoted herself single-mindedly to holding Trump accountable for plotting against the constitutional order. She did so knowing it would cost her the support of her party and her constituents, ending her career. She now travels with a security detail, a predictable consequence of making herself a prominent enemy of the leader of a personality cult. In those facts lie the essential ingredients in honor—selflessness and self-discipline in service of virtue.

Yet, among GOP voters, Liz Cheney may be the least popular politician in the country. Why?

Some anti-Trump conservatives speculate that Trump’s sycophants in Congress despise Cheney out of jealousy. Their own vestigial sense of honor is irritated by her example, the theory goes: They resent her because they lack the character to behave as virtuously as she has. I think that gives them entirely too much credit. Not for a moment do I believe that Elise Stefanik, say, lies awake at night tortured by her conscience, wondering why she can’t be more like the woman she elbowed aside to join the House GOP leadership.

To the extent Stefanik gives Cheney any thought at all, I suspect she feels contempt for her perceived personal weakness. Imagine giving up a path to the speakership over something as frivolous as a crisis of conscience. The opportunists in the party don’t disdain Cheney because they envy her or even because she’s aligned with Democrats against Trump. They disdain her because she’s a sucker, too soft-headed about gassy intangibles like duty to do what’s needed to claim power.

They think she’s a chump. A Boy Scout.

Politicians tend not to care about honor. They wouldn’t be politicians if they did. But voters do, or at least feel obliged to pretend that they do, and so Cheney’s example is trickier for rank-and-file Republicans to reckon with. The way they tend to do so is by accepting the premise that honor matters but challenging her claim to it. It’s why her critics so often accuse her of coveting a job on CNN or MSNBC as an anti-Trump talking head, as if being a loud and insistent Trump apologist isn’t a more lucrative career path for a conservative. They question her motives because they’re keen to assure themselves that she hasn’t actually behaved selflessly by defying Trump—rather, that she’s gained by doing so.

More than that, they dispute that she’s behaved honorably by rejecting the idea that she’s behaved virtuously. That’s a hard pill for you or I to swallow, but for an ardent partisan it’s the easiest piece of this puzzle. Since concentrating power in the GOP and denying power to the Democrats is allegedly America’s only path to virtue, Cheney’s efforts to weaken the party by exposing Trump’s corruption are dishonorable per se. Loyalty too is a hallmark of honor, after all, and to a devout partisan the only way to show loyalty to the country is to show loyalty to the party. A willing dupe for Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats has betrayed the United States, by definition.

All of these strands about honor are tangled up in populist politics in the person of Trump.

I’ve always wondered about the famous Atlantic piece that accused Trump of having called American soldiers “suckers.” No one can prove that he said it, but the soldier’s ethos of supreme sacrifice for the common good is plainly antithetical to Trump’s philosophy of always, always looking out for number one. If he doesn’t quietly believe the average enlisted man is a “Boy Scout” and a chump, it’s completely out of character.

To call Trump dishonorable is true but uninteresting inasmuch as many politicians behave dishonorably. The interesting distinction between him and them is how he’s fashioned dishonor into a political virtue in its own right, the acid test of a strong leader’s resolve not to be deterred by conventional expectations of propriety when pursuing his interests. And not just his political interests: Tellingly, when Trump dismissed Paul Ryan as a Boy Scout during their first meeting, it wasn’t in the course of a disagreement over policy. They were discussing the Access Hollywood tape, which had scandalized Ryan by giving him a glimpse of how shamelessly Trump prioritized self-interest over propriety in his grubby personal life.

Even before the Access Hollywood episode, some voters found themselves captivated by the apparent causal relationship between Trump’s indomitable shamelessness and his fabulous success. He was a well-known philanderer; he was infamous for stiffing creditors; he lied and lied about his charitable giving; he ran multi-million-dollar rackets. He was a con artist through and through—yet the world rewarded him lavishly for it. He dated beautiful women, flew on a private jet, lived in a luxury apartment, and had billions in the bank (or so he said). Some supporters came to view him as a sort of guru, embodying “a highly motivating philosophy of positive thinking and the virtues of self-love and brazening things out, as real men do.” He pursued the things he desired, sneered at everyone who told him his methods were shameful, and emerged the consummate winner.

Steve Bannon once described the aftermath of the Access Hollywood episode in 2016 as a “litmus test” for Republicans, which was truer than even he knew. By “litmus test” Bannon meant a pedestrian test of loyalty to the party’s nominee for president, which some Republicans failed by retracting their endorsements of Trump after the tape emerged or by calling on him to withdraw from the race. Trump ignored them and battled on, formally apologetic yet functionally defiant, and a month later he and his party were handed total control of government. That cemented his reputation on the right as a fighter willing and able to push on to victory no matter how many disapproving clucks from polite society he drew.

A lesson was learned there: Dishonor was no obstacle to power. Not only was it no obstacle, but inasmuch as it demonstrates strength of will, a shameless willingness to behave dishonorably might turn out to be the path to it. The real litmus test for Republicans was whether they were willing to continue on that path, on those terms.

If success is fundamentally a matter of will, norms that aim to thwart one’s will are naturally to be despised as enemy contrivances, booby traps set by Boy Scouts to waylay the strong. It doesn’t matter what the norm is, whether public or personal, or whether it relies on shame or something sterner as sanction. A strong man is a dishonorable man, ruthless in pursuit of his goals and untroubled by the civic hobby horses of weaklings. You can draw a straight line between that logic and January 6, 2021.

Ruthlessness in pursuit of cultural dominance has become the unspoken credo of Trumpist populism. Not all populism, to be sure: One might be a populist, for instance, because one supports redistributing wealth to working-class families. Although it’s worth noting that, by that definition, the most prominent populist in the party right now happens to be the most prominent member of the pre-Trump Republican establishment.

Trumpist populism doesn’t concern itself with redistribution; it concerns itself with cultural revanchism. And its animating principle is that if you’re not prosecuting the culture war with maximum ruthlessness, willing to go to illiberal lengths that would make Reagan-era conservatives blanch, you’re not fighting hard enough. Here’s J.D. Vance, an outspoken Trump-endorsed populist and likely the next senator from Ohio, fantasizing about what sort of norms might eventually be swept away by the right’s shameless pursuit of dominance in an interview earlier this year:

“I tend to think that we should seize the institutions of the left,” he said. “And turn them against the left. We need like a de-Baathification program, a de-woke-ification program.”

“I think Trump is going to run again in 2024,” he said. “I think that what Trump should do, if I was giving him one piece of advice: Fire every single midlevel bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, replace them with our people.”

“And when the courts stop you,” he went on, “stand before the country, and say—” he quoted Andrew Jackson, giving a challenge to the entire constitutional order—“the chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.”

…

“We are in a late republican period,” Vance said later, evoking the common New Right view of America as Rome awaiting its Caesar. “If we’re going to push back against it, we’re going to have to get pretty wild, and pretty far out there, and go in directions that a lot of conservatives right now are uncomfortable with.”

It’s no coincidence that a menagerie of kooks, grifters, performance artists, and not-even-barely-veiled fascists like Vance would end up in orbit around a figure like Trump, a figure who converted their most embarrassing trait, shamelessness, into a virtue. Especially the fascists: One can’t glorify the transgressive bravado of dishonor without eventually glorifying authoritarianism, I think. Liberalism aspires to maximize the freedom of the governed through a series of laws and norms designed to restrain the government; a government led by a man who’s unwilling to restrain himself in pursuing his interests will necessarily be illiberal. That being so, it’s also no coincidence that Trump reserves his most admiring compliments of other world leaders for fellow authoritarians.

Vance was thinking big-picture in the comments quoted above, but the populist ethic of ruthlessness shows up in more mundane cultural flashpoints. Earlier this year in Florida, Ron DeSantis responded to mild criticism from Disney of his so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill by moving to revoke the company’s special improvement district for Disney World, as flagrant a case of viewpoint discrimination by a government official as one will ever see. To Trumpists, DeSantis’ willingness to use state power to intimidate political opponents is a badge of dishonor, making him the only credible alternative to Trump in a 2024 presidential primary. Like Trump, he “fights”—by which they mean that he’s willing to behave illiberally to dominate the right’s enemies. And by no means is he the only ambitious Republican keen to signal his willingness to do so.

Ruthlessness, like shamelessness, demonstrates resolve and nothing quite communicates ruthlessness in modern Republican politics like barreling across a red line drawn by classical liberalism in pursuit of one’s foes. It’s because Liz Cheney opposes populism’s most illiberal impulses that she now qualifies as a “RINO,” never mind that her voting record is far more conservative than the Trumpy moderate Stefanik’s. Cheney would rather risk having Democrats win within America’s civic tradition than ensure Republicans win by smashing it. To you and I, that’s evidence of honor. To the sort of MAGA edgelord given to burbling “they hate you” all day long on right-wing Twitter, it’s a Boy Scout’s pitiful seduction by weakness.

“Suckers” versus “fighters.” It’s the subtext of all disputes between us. Which one are you?

We’ll have many occasions to revisit that subtext in future editions. If you haven’t subscribed to The Dispatch yet, please do so and take advantage of the discount before it disappears.

The title of this newsletter, by the way, comes from the urban legend about how frogs supposedly behave when dumped into a pot of water. If the water is boiling, they’ll leap right out. But if the water starts off lukewarm and the temperature rises gradually, the slight incremental changes will be imperceptible moment to moment and the frogs will ultimately boil alive. It’s nonsense, of course; frogs have the good sense to act when an unpleasant environment turns dangerous. We, however, might not.

On that note, I leave you with a question: At what point should a candidate’s illiberalism become disqualifying? Vance is on the ballot in Ohio. Election deniers like Kari Lake and Doug Mastriano are one race away from governing swing states. Trump diehards across the map have been nominated for secretary of state, which would place them in charge of their state’s election machinery in 2024. Trump remains the party’s presumptive nominee for president notwithstanding his coup attempt on January 6, 2021 and his habit of threatening violence if the justice system challenges his belief that he’s above the law. And if he ends up losing the next primary, it’ll only be because Ron DeSantis has convinced Republicans that he’ll be as ruthless in flouting civic norms as Trump would be when prosecuting the culture war.

The temperature of the water is getting hotter. How sure are you that you know what your party’s candidates are capable of? When should a conservative voter leap out of the pot?

If the answer is “never,” and most “fighters” would say it is, then they should also say forthrightly that they’re intent on seeing us all boil. There’s some honor in honesty, even among the dishonorable.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.