Correct me if I’m wrong, as I haven’t read The Art of the Deal. But when starting a negotiation, it’s normally not good practice to open by offering the other side nearly everything it wants, right?

Last month the Washington Post summarized Moscow’s endgame in a peace deal with Kyiv and Washington as creating “a neutral, demilitarized Ukraine outside of NATO, with Russia keeping the territory it has already annexed.” This morning the Fox News host who now commands the U.S. military said this:

So Russia will indeed keep at least some of the territory it purports to have annexed, it appears, with America’s blessing. U.S. policy since 2014 has been that Crimea belongs to Ukraine and is under Russian occupation; with Pete Hegseth now writing off a return to the pre-2014 borders as “unrealistic,” the White House is presumably abandoning that policy and, with it, Ukraine’s claim to the peninsula.

NATO membership for Ukrainians also looks to be off the table. Hegseth went out of his way to say that the United States won’t be involved in any European peacekeeping operations in Ukraine and that, if those peacekeepers end up being shot at by Russia, America’s Article 5 obligations to defend NATO allies won’t be triggered. Simply put, there will be no U.S. security guarantees for Kyiv.

Our boys in uniform have more important things to do, like turning Gaza into a resort while occasionally being blown up by Hamas suicide bombs.

As for Russia’s desire for “a neutral, demilitarized Ukraine,” that’s still TBD. But as recently as Monday, Donald Trump casually observed that the country “may be Russian someday.” Moscow ultimately getting everything it wanted out of this war, albeit at immense cost, remains a live possibility.

Seems bad. Yet, for the second time in a week, I find myself surprisingly conflicted about Donald Trump’s foreign policy.

After all, fair is fair: As strange as it might seem for him and Hegseth to concede Russia’s 2014 land grabs before peace talks have begun, it’s obviously true that pushing Vladimir Putin’s army out of Crimea and the Donbas is “unrealistic” at this point. Even Volodymyr Zelensky recognizes that territorial concessions will be necessary. How mad can one be at the White House for recognizing reality?

And how forgiving can one go on being of Europe and Ukraine for not recognizing the new reality of geopolitics at this late date?

A new reality.

What Zelensky wants in exchange for handing over territory to Russia is NATO membership. The only way Ukrainians can live with rewarding Moscow for its war of conquest by forfeiting land, he has suggested, is if Western nations promise to join them in the fight the next time Putin crosses the border.

And by “Western nations,” he means one very specific Western nation. “There are voices which say that Europe could offer security guarantees without the Americans, and I always say no,” he told the Guardian recently. “Security guarantees without America are not real security guarantees.”

That’s not entirely true. Some European allies, including Britain, have opened the door to sending peacekeepers to enforce a ceasefire. French President Emmanuel Macron is talking tough about continental power, as is his wont, even framing it as a matter of earning Trump’s respect. One regional military official told Politico that “[w]e will, for the moment, take the lead if the Americans don’t.”

But no one, least of all Zelensky, expects European nations to commit to a war with Russia without American power behind them. Yet American power won’t be behind them; that was the point of Pete Hegseth’s comments at a Brussels defense summit Wednesday morning.

That’s been abundantly clear since November 5—yet Zelensky has gone on hoping for a U.S. military backstop to his country’s security. Why? How can Ukraine, never mind its European patrons, still be under the illusion that Donald Trump’s America might spend blood and treasure on its behalf?

“Trump’s reelection means the end of the Pax Americana,” I wrote the morning after the election. “He may or may not recall U.S. troops from Europe and the Far East, but the era of U.S. allies depending on America’s commitment to Western liberalism is plainly over. And that era won’t return after Trump leaves office: NATO countries would be insane to ever again bet on the good sense of the American voter.”

Even when Trump began uncharacteristically threatening Russia a few weeks ago, I thought it was nutty to believe that he or some postliberal successor would ever keep a promise to send U.S. troops into battle against Russia, whether under the auspices of NATO or otherwise. We don’t live in that world anymore.

The virtue of candor.

And so I prefer to have Hegseth rule out U.S. security guarantees for Ukraine candidly, as he’s now done, than to see him lie by making a pledge that the White House has no intention of keeping. The sooner free nations are made to understand that “this is no longer the America we used to know,” to quote Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting, and that Washington is now somewhere between indifferent and hostile to the survival of Western liberalism, the sooner those nations will adapt and hopefully fill part of the security vacuum before China and Russia do.

That Europeans haven’t done more to adapt already is strange to me, frankly. “It’s a safe bet that in 15 to 20 years’ time, the American priority will be its own defence, and much more so around and in the China Sea than in Europe,” Macron told his advisers last month, seemingly overestimating the U.S. commitment to the continent by … 15 to 20 years.

In fact, Zelensky reportedly spent the first three weeks of Trump’s presidency being ignored by the White House. The president of Ukraine has had “only minimal contact with the new leader of the free world: just ‘a couple of calls’ since a meeting in September,” The Economist reports. “He is not being informed about contacts between the White House and the Kremlin; what he knows he gets from the press like everyone else.” The Ukrainians apparently now fear that Trump and Putin are brokering some sort of Munich-style sellout behind their backs.

The counterargument to this case for candor is that strategic ambiguity has certain deterrent virtues and that Trump and Hegseth shouldn’t be telling Moscow that the U.S. won’t intervene the next time Russia invades Ukraine. I disagree. Nothing will goose Europe into hurriedly adapting to the new world order like seeing the U.S. formally retreat from Western leadership. And as I say, even if Trump had vowed to guarantee Ukraine’s security, no one expects an “America First” president to actually follow through, including Vladimir Putin. Who would be deterred by a transparently empty promise, exactly?

Candor is clarifying. If you’re a liberal regime with the misfortune to have an authoritarian predator as a neighbor, you’ve received what’s tantamount to official notice from Washington that you should begin building nuclear weapons post haste. We’ll know that the hard truth about the end of the Pax Americana has finally sunk in if news starts trickling out this year that various U.S. allies—Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Japan, South Korea, uh, Canada—are developing nuclear bombs and the requisite delivery systems to keep the wolf at their door away.

When the world’s policeman walks off the beat, the only way to protect yourself is to grab the biggest gun you can find and prepare to shoot to kill. I marginally prefer a world that looks like The Purge to one governed by a Pax Sinica.

But if we’re going to have clarity, let’s have clarity all around. Let’s stop pretending that the reason Trump, Hegseth, and other MAGA disciples want to pull back from Europe is because they’re so gosh-darned focused on containing China.

Excuses, excuses.

Any time a hawk criticizes the president’s isolationist tendencies, some MAGA apologist starts squawking about China. It’s not that Trump wants to retreat from NATO and Europe, we’re told, it’s that he has to. America has only so many ships and planes and tanks and men so it needs to prioritize judiciously in how it allocates military resources. Clearly, a rising power with the world’s largest population is a higher priority than a declining power that’s about to enter year four of trying to subdue Ukraine.

Hegseth mentioned China repeatedly in his comments to reporters this week in explaining why the United States just doesn’t have the bandwidth to prop up Europe long term, let alone Ukraine. And I don’t blame him: The logic of it is insuperable. Chinese power threatens the United States, Russian power doesn’t, so we’re going to focus on addressing the more urgent risk.

Containing China, not Russia, has been a pillar of Trump’s “America First” worldview since 2015, in fact. In addition to the obvious compelling strategic realities, it’s extremely on-brand for his protectionist politics. Who better to serve as a global arch-foe for populists than the country to which so many American jobs were offshored?

We can’t contain Russia because we have to contain China. It’s airtight. Except for one thing: Where is the evidence, exactly, that the president intends to contain Beijing in his second term?

Politico considers his record thus far:

Since taking office on Jan. 20, Trump has frozen U.S. foreign aid in numerous countries while taking steps to shrink the U.S. Agency for International Development, endangering humanitarian and economic aid for millions in places where the Chinese government has sought to increase its influence. He has weakened his shot at convincing allies to move away from China by taking steps to impose tariffs on Mexico and Canada, two of America’s friends, neighbors and top trading partners. He has allowed tech mogul Elon Musk to take steps to gut the U.S. federal workforce, a move that tosses out an enormous amount of expertise in fields such as fighting Chinese propaganda. He has mocked the rule of law and Congress in a way that reinforces Beijing’s top-down leadership structure. And he has threatened to invade other countries, including U.S. partners—rhetoric that could embolden China to further menace Taiwan.

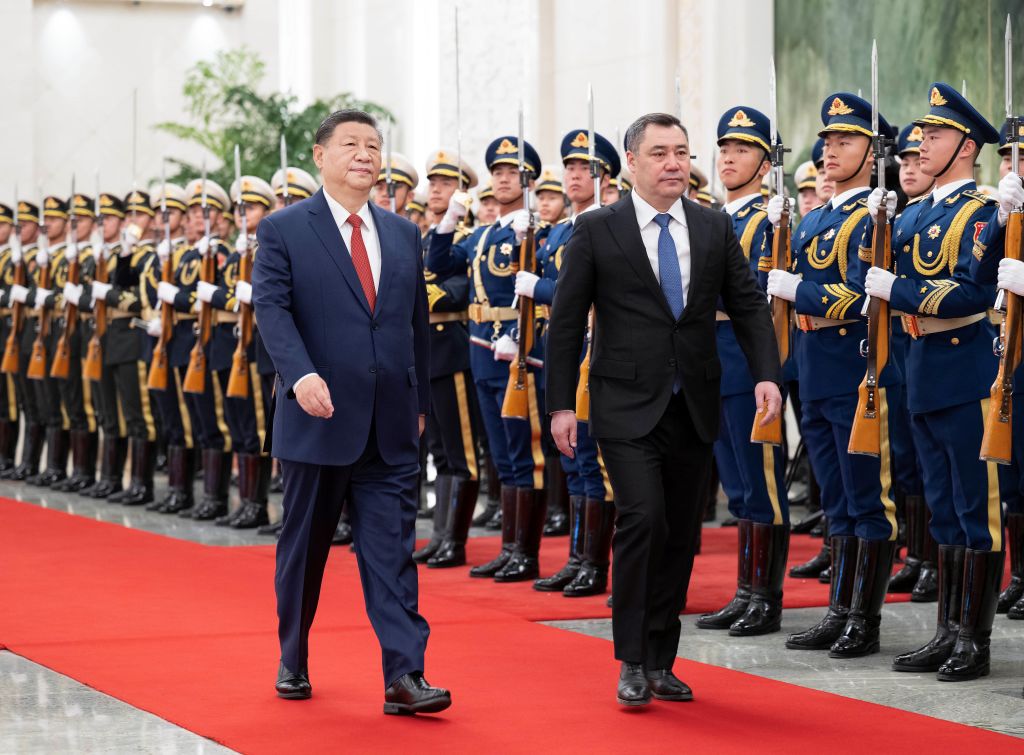

He’s also working hard to rescue the Chinese government’s favorite spy app, promised to slap tariffs on Taiwanese semiconductors, and has created all sorts of diplomatic opportunities for Beijing by rug-pulling American soft power abroad. He even invited Xi Jinping to his inauguration, an honor not typically granted to enemies.

About the only thing Trump has done that’s clearly anti-China is to slap a 10 percent tariff on Chinese imports, but even that isn’t as clear as it might seem. After all, he was prepared to impose comparatively draconian 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico until a market convulsion drove him to postpone them. He’s promised that tariffs on the European Union are coming. And he has in fact already imposed 25 percent tariffs on steel and aluminum imports—globally, on allies and enemies alike.

If tariffs are his big weapon to contain China, it’s weird that we’re “containing” a lot of other, friendlier nations far more aggressively right now.

Spheres of influence.

“One of my hottest takes about Trump’s second term is that his relations with China will be much warmer than anyone expects,” I wrote three days before the inauguration, offering numerous receipts. That prediction looks better every day. Trump doesn’t care about “containing” China, as far as I can tell, he cares about restoring what he perceives as “balance” to trade between the two countries. If Beijing will work with him on that, I think he’ll be willing to work with them on lots of things—by no means all of them trade-related.

Last month The Economist imagined the president offering “a great-power bargain that Mr Xi could accept—perhaps bundling economic trade-offs with a divvying-up of the world into spheres of influence.” Part of that bargain, one expert surmised, would see the White House cast aside Taiwan by formally opposing its aspirations for independence, “transforming politics inside the island and pouring cold water on Western governments that have taken up Taiwan’s cause as a test of democratic solidarity.”

Trump being Trump, a great big, beautiful, amoral deal with a menacing totalitarian power seems far more plausible than him committing his entire military chip stack to defending Taiwan, a country that’s at least as alien to the United States culturally as Ukraine is. The idea of him wanting to carve the world up into “spheres of influence” also rings true: He seems more interested early on in bullying Greenland, Panama, and Canada than in making sure China doesn’t threaten Japan or South Korea, don’t you think?

A postliberal (or pre-liberal) world order in which the United States, China, and perhaps Russia each operate unchecked in its respective “sphere of influence” would be the opposite of containment. We wouldn’t interfere with the Chinese when they went about bullying lesser powers in the Far East and they wouldn’t interfere with us bullying lesser powers over here. In practice, that arrangement would amount to abandoning long-standing American allies to the hegemony of one of the most sinister regimes on earth. “As long as they don’t touch Hawaii!” MAGA types might answer.

Rest assured, as China gains territory and confidence in its imperial ambitions, eventually they will try to touch Hawaii.

But surely our sharp ideological differences will force a confrontation between us and them before then, no? “As far as external threats, there’s just no doubt the communist Chinese ambitions are robust,” Hegseth told reporters on Tuesday. “Their view of the world is quite different than ours, and whoever carries that mantle is going to set the tone for the 21st century.”

But that’s just it. I get no real sense from Trump or his populist “America First” acolytes that they’re engaged with China in a zero-sum ideological competition for global dominance à la the Cold War. Rather the opposite. Trump openly admires authoritarian “strength” and struggles to contain his excitement when some foreign caudillo exerts his will to power on a weak neighbor.

You’ve watched him as often as I have over the last nine years. With whom, would you say, does he feel a greater degree of ideological kinship—Putin or Zelensky?

I believe that the president believes the world is plenty big enough for illiberal American, Chinese, and Russian regimes to prey on countries in their respective spheres of influence in peace and harmony. And I further believe that lots of influential populists who have feigned being “tough on China” to this point because “America First” required some sort of international foil to appeal to swing voters will show their true colors once it becomes politically safer for them to do so. Foreign fascists have always seemed to irritate them less than the liberal “enemy within.”

So “containing China” is ultimately an excuse, sound in theory but in practice a pretext to justify withdrawing from defense of the Western liberal order. Trumpists aren’t opposed to guaranteeing Ukraine’s security because they’re too busy strategizing about how to rein in Beijing, they’re opposed to it because they reject in principle the idea that Americans should sympathize more with Ukrainian or Taiwanese liberals than with Russian or Chinese strongmen. It would be nice if the last handful of Reaganites in the GOP came to grips with that, and with the reality of the end of the Pax Americana, instead of stupidly trying to warn Trump of what will happen if he abandons Ukraine. Trust me, Mike: He knows.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.