If you’ve ever lived in New York City, as I did for most of my life, you know how it feels when a panhandler announces himself to a crowded subway car. Excuse me, ladies and gentlemen, may I have your attention …

First comes sympathy, then a shameful twinge of resentment that the tranquility of your ride has been rudely interrupted by a fellow human being’s starvation. Then comes a sense of low-grade alarm.

Most panhandlers are harmless and move on to the next car after they’ve received a few donations. But to arrive at a state where one is reduced to begging for money on the subway usually involves mental illness or drug use or both, as everyone present is keenly aware. You know that the man before you is probably in an altered state of one sort or another.

And people in altered states, especially those with nothing to lose, are unpredictable.

On Monday afternoon a man named Jordan Neely entered a car on the F train. Neely was once known to New York subway riders as a busker with an unusual angle, dressing up as Michael Jackson and showing off his dance moves. But that was years ago; he’d fallen on hard times since. When he addressed the passengers on Monday, he wanted help. And unlike most panhandlers, he wasn’t polite about it.

Juan Alberto Vazquez, a freelance journalist, happened to be in the same car. According to him, Neely began screaming, “I don’t have food, I don’t have a drink, I’m fed up. I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison. I’m ready to die.” I rode the subway every weekday for four years as a high-school student in the early 1990s, an era when crime in New York City was much worse than it is now, and I never once heard anyone announce that he’s ready to die.

If I had, the alarm I felt wouldn’t have been “low-grade.”

Neely didn’t just yell. Evidently he threw garbage at some of the passengers and took off his jacket and flung it to the ground. Newsweek reported on Thursday morning that he had no fewer than 42 prior arrests, most for minor offenses but four for assault—including an outstanding warrant on that charge. Vazquez says he was frightened but he concedes that Neely never actually assaulted anyone during Monday’s incident. “It was a very tense situation because you don’t know what he’s going to do afterwards,” he told the New York Times.

At some point a passenger, who turned out to be an active-duty Marine, stood up and confronted Neely. The Marine got behind him and grabbed him in a chokehold, bringing him to the ground. At least two other passengers moved in to help restrain him. Neely struggled, his arms and legs flailing, but the Marine wrapped his own legs around him and maintained his chokehold.

For 15 minutes, according to Vazquez.

Vazquez recorded the last four minutes of the incident, which you can watch here. At around two minutes in, a passenger warns the Marine that he’s at risk of killing Neely. “If you suffocate him, that’s it,” he says. “You don’t want to catch a murder charge.” One of the others helping to restrain him replies that “He’s not squeezing no more,” at which point the Marine finally releases his grip.

By the Times’ count, Neely continued to be held down for around 50 seconds after he stopped moving. “He wasn’t conscious, he wasn’t responsive, and the man still had him in the headlock,” an eyewitness told the New York Daily News.

When New York police finally—finally—arrived, he was unresponsive and was later pronounced dead at a hospital in Greenwich Village. The cause, according to the medical examiner: Homicide, due to “compression of neck (chokehold).”

An investigation is ongoing but the Marine hasn’t yet been charged. As of Thursday morning, despite choking a man out on video, he wasn’t even in custody. Protests in New York City have already begun, with more to come.

So far the reactions to this horrendous incident among partisans on social media are what you’d expect and doubtless will turn more obnoxious as they polarize further. In American politics, even death is tribal.

I have my own tribal biases, although lately not the ones I had for most of my life. I used to presume that the leftist take on any given subject wasn’t just wrong but informed by malice, however concealed. In the Trump era, my presumption has shifted: If the populist right is animated over some controversy, chances are the other side of the issue is the morally correct one.

Search Twitter today for the phrase “Hobo Floyd” to get a taste of their commentary on Jordan Neely’s death. They seldom disappoint.

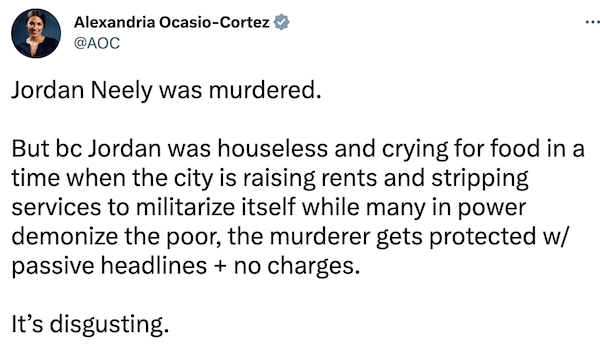

I agree with them on this much, though: However else one might describe what happened to Neely, it almost certainly wasn’t “murder.” One would think progressives who occupy an office of public trust would be careful about throwing that word around, but one would be wrong.

Murder is a crime of intent. There’s no reason to think the Marine and the other passengers who restrained Neely intended to kill him. They released him after he stopped struggling, presumably believing they had neutralized the threat and that he’d come to once he was in custody.

Ocasio-Cortez is reaching for a word with special moral power to capture her outrage that a man might be killed on camera, in broad daylight, with no consequences (so far) because he was the lowest of lower-class, but words mean things. “Murder” is a legal term with a particular meaning. Ultra-influential members of Congress should take care with what they say at a moment when civil unrest is brewing.

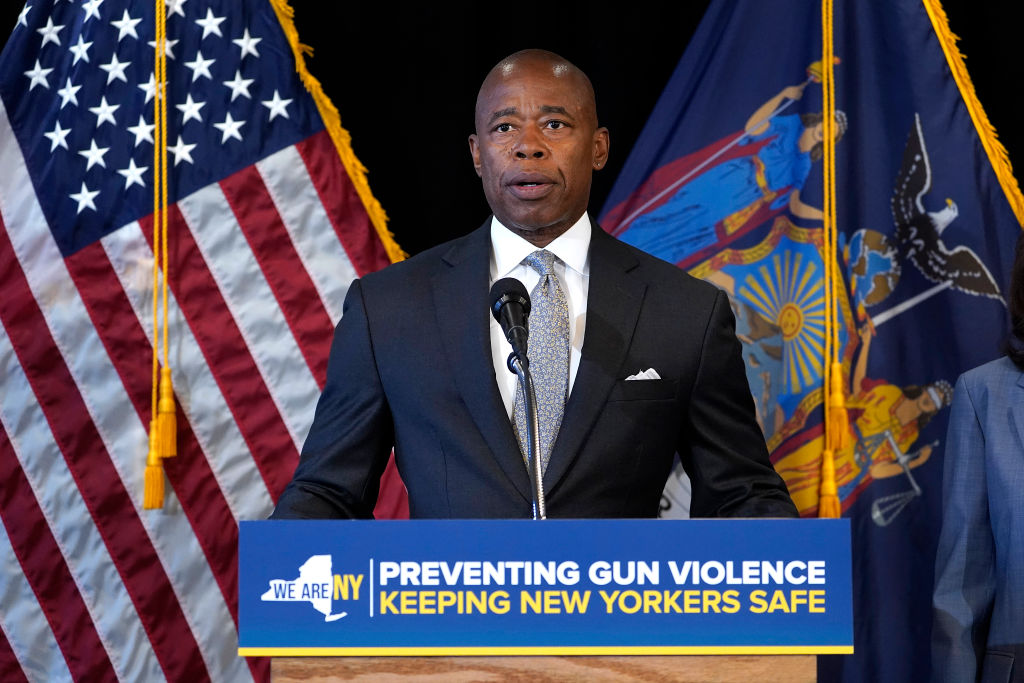

Some local politicians went further than AOC did, calling Neely’s death a “lynching.” It fell to New York Mayor Eric Adams, a tough-on-crime former cop, to demonstrate caution. When he was asked during an interview whether subway passengers are guilty of vigilantism when they intervene to subdue someone, he said, correctly, that it depends on the situation. Later, in a statement, he addressed Neely’s death by conceding that it’s tragic while adding, “There’s a lot we don’t know about what happened here, so I’m going to refrain from commenting further,” and noted that “serious mental health issues” were involved. That’s also the correct response. Neely was behaving aggressively; until the police determine how aggressively, it’s irresponsible to pronounce the men who subdued him murderers.

Ocasio-Cortez didn’t care. She responded to Adams by doubling down and accusing him of condoning a “public murder because the victim was of a social status some would deem ‘too low’ to care about.”

For progressives, the lessons from Neely’s death are straightforward. However much the city is spending to reduce homelessness, and it’s spending a lot, it’s not enough. His aunt told local media that he was schizophrenic and became depressed after his mother was murdered in 2007 but never got the help he needed: “The whole system just failed him. He fell through the cracks of the system.” If America devoted more resources to improving mental health, this wouldn’t have happened.

There’s a racial lesson too. Neely was black and his killer was white so in this case the killer has had every benefit of the doubt. The state senator who described the incident as a “lynching” said “she doesn’t think Neely would have been perceived as a threat if he wasn’t black. And she said that if the perpetrator were black, he’d likely be in custody,” according to Gothamist. As for the right-wingers who are rallying to that killer’s defense, they might say “all lives matter” to rebuke the Black Lives Matter movement but their actions in this case prove once again that they don’t mean it, that they value black life cheaply.

The tribal politics of the incident are sensational, almost as much as the famous Bernie Goetz episode to which it’s already being compared. But it obviously wasn’t murder. Even Vazquez, the best witness to what happened, insists that the Marine was “trying to help.”

Was it a crime, though?

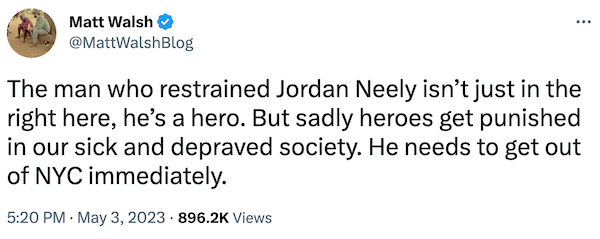

Of course not, say the right-wingers who have drawn different lessons from Neely’s death. Conservative talk radio host John Catsimatidis summed up their position when, while covering the incident, he played a soundbite from Charles Bronson’s vigilante fantasy, Death Wish: “If the police don’t defend us, maybe we ought to do it ourselves.”

I have elderly relatives in New York and there are few topics that animate them as much as the growing danger of riding the subway. They hardly ever do so themselves, mind you, but the sense that anyone who does is at risk of encountering a dangerous vagrant at any moment is real and widespread. There were 10 killings on the subway last year, up from an average of two before the pandemic, and many reports of homeless people sleeping in cars in 2021.

More cops in the system led to a drop in major crimes on the subway over the last quarter of 2022 but the belief that chaos reigns will die hard, particularly with a notoriously “soft on crime” district attorney in charge in Manhattan. That’s why Adams and Gov. Kathy Hochul are choosing their words about this incident verrrrry carefully. The average New Yorker is in no mood, it seems, to be told that they should get comfortable with being threatened in public by mentally unstable people.

Are they willing to see those people lawfully strangled to death, though?

Some right-wingers are.

Ben Shapiro went further and blamed the left for Neely’s death.

I read that and feel my tribal biases irritated, knowing that a core conviction of Trumpism is the belief that every problem can be made less troublesome by the application of more violence. Illegal immigrants flooding the border? Shoot them in the legs. Fentanyl epidemic in the heartland? Bomb the cartels. BLM protests spiraling into riots? Invoke the Insurrection Act. D.A. breathing down your neck? Threaten “death and destruction” if you’re charged. Demonstrators disrupting your rallies? Offer to pay the legal fees of anyone who assaults them. Risk of a floor fight at your party’s political convention? Warn of riots if it happens. Lost a presidential election? Instigate a mob to overturn it by force.

Alarmed by an unstable homeless person on the subway? Choke him until he stops moving.

When all you have is an authoritarian hammer, everything looks like a nail.

I’m also mindful of how this incident “codes” for right-wing populists. It’s not a police shooting, but there’s a reason why the Marine pedigree of the passenger who killed Neely is mentioned so often in the coverage. On Fox & Friends this morning, host Brian Kilmeade described the incident this way: “You have a 24-year-old who we trained in the military, lives on Long Island, hopping on a subway, and said let me help out the American people again when I’m not in Afghanistan, let me just grab this guy and hold him down. No cops around because they are understaffed and they are not on the trains. They are upstairs. And this guy takes action.”

We trained him. He served America again.

Whether or not you believe there’s a racial component in how the right views what happened, the fact that the killer was a Marine makes the “law and order versus crime and chaos” salience that much more potent. By the time this story runs its course, the guy will be getting invites to speak at Turning Point USA events amid video pyrotechnics dubbing him “The Punisher.”

Let’s lay our tribal biases aside, though, as questions of law should never depend on such things. Consider the question objectively. Will the Marine end up doing time for killing Jordan Neely after the liberal-dominated justice system in New York City is done with him?

If I had to bet, I’d bet no.

There are numerous offenses in New York state’s penal code with which he might plausibly be charged. One obvious possibility is criminally negligent homicide: “A person is guilty of criminally negligent homicide when, with criminal negligence, he causes the death of another person.” Criminal negligence is defined as the failure “to perceive a substantial and unjustifiable risk that such result will occur or that such circumstance exists. The risk must be of such nature and degree that the failure to perceive it constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the situation.”

Choking a man for 15 minutes, and continuing to choke him for a bit after he stops moving, might plausibly be described as a gross deviation from how a reasonable person would manage the risk of accidental death.

If that’s not harsh enough for you, there’s always manslaughter in the second degree, of which you’re guilty if you “recklessly cause the death of another person.” Recklessness involves a greater sense of awareness of wrongdoing than criminal negligence does. Instead of failing to perceive a substantial and unjustifiable risk, the offender is “aware of and consciously disregards” it.

Remember the passenger who warned the Marine and the other people restraining Neely that they might kill him if they keep it up? There’s your recklessness charge, potentially.

If charges related to Neely’s death are too ambitious, the local D.A. could charge the Marine with a lesser offense. The crime of “criminal obstruction of breathing or blood circulation” occurs when “with intent to impede the normal breathing or circulation of the blood of another person, he or she … applies pressure on the throat or neck of such person.” That’s a misdemeanor. One step up is strangulation in the second degree, a felony, which is defined the same way except that restricting the victim’s breathing “thereby causes stupor, loss of consciousness for any period of time, or any other physical injury or impairment.”

The question isn’t whether the Marine broke the law. The question is whether he had a valid justification to do so.

“A person may … use physical force upon another person when and to the extent he or she reasonably believes such to be necessary to defend himself, herself or a third person from what he or she reasonably believes to be the use or imminent use of unlawful physical force by such other person,” says Section 35.15 of the Penal Code. Was it reasonable for the Marine to believe force was needed?

Well, remember what Neely said: “I don’t have food, I don’t have a drink, I’m fed up. I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison. I’m ready to die.”

Remember that Vazquez was frightened. And remember that at least two other passengers helped restrain Neely, evidence that it was objectively reasonable to believe that he might do something violent if he got free. The fact that Neely had been arrested for assault multiple times before wasn’t known to the passengers, of course, but that would have made their use of force even more reasonable.

It’s notable that he never harmed anyone in the car, either because he didn’t intend to or because he never got the chance, but actual harm isn’t required to justify self-defense. The law merely requires a reasonable belief that the victim was about to use unlawful force imminently. Was it reasonable for the Marine to believe that?

Seems plausible, sure.

Where this gets tricky is in how the law defines the use of deadly force in defense of oneself or another.

A person may not use deadly physical force upon another person under circumstances …unless … the actor reasonably believes that such other person is using or about to use deadly physical force. Even in such case, however, the actor may not use deadly physical force if he or she knows that with complete personal safety, to oneself and others he or she may avoid the necessity of so doing by retreating …

Was Neely’s declaration that he’s “ready to die” sufficient to create a reasonable belief that he was about to use deadly force? As far as I’m aware, he wasn’t armed. But the passengers didn’t know that.

The Marine had no duty to retreat in this case, presumably, because there was no way to do so while assuring the “complete personal safety” of the other passengers. There was nowhere to go: Had they moved to the next car, Neely might have followed them in.

The tricky part is whether, at some point during the incident, the Marine’s use of deadly force went from reasonable to unreasonable. It was reasonable to place him in a chokehold to stop him from hurting anyone. But what about maintaining that chokehold after he stopped moving?

I conferred with my colleague Sarah Isgur about this since, between the two of us, she’s the lawyer who knows what she’s talking about. Bearing in mind that her analysis is based only on the incomplete early reporting, she suspects the Marine’s case will be brought to a grand jury—and that they’ll decline to indict. Testimony from the passengers that they were scared and testimony from the Marine that he never intended to hurt Neely will probably tip the balance toward reasonableness, even if it’s murky whether the choking should have gone on quite as long as it did.

But a grand jury will surely be convened. It’s unthinkable that Alvin Bragg or any other district attorney would send the message to the public that you’re free to strangle a menacing derelict in New York City without even glancing contact from the American justice system. If the left is destined to be disappointed by the Marine getting off without prison time, Bragg would rather have a grand jury on the hook for that decision than have to explain to progressives why he refuses to pursue charges.

So expect an investigation and all of the tribal nonsense that will entail. Possibly ending with the Marine as the next keynote speaker at CPAC.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.