Typically when a presidential candidate is putting up mega-landslide margins in the early primary states, it’s clear to all that he’s on his way to becoming his party’s nominee.

Nothing is typical in American politics anymore.

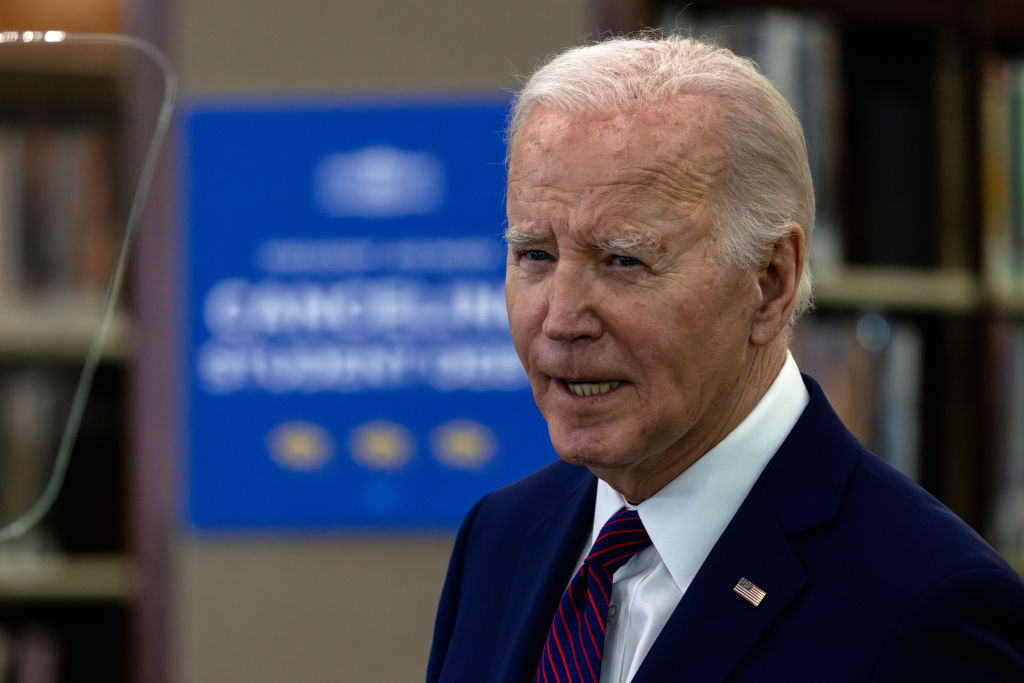

Ask the average Republican voter (or average Republican presidential frontrunner) which Democrat will top the ballot this fall and you’ll be surprised at how few, even now, answer “Joe Biden.” Some assume the president can’t conceivably last another eight months, believing that he’s been living on borrowed time for years. But for many, it’s not the Grim Reaper blocking his path to a second term. It’s Michelle Obama.

A “rumor” (i.e. a conspiracy theory) has circulated for months among the right-wing faithful that Barack Obama’s better half will, by hook or by crook, replace Biden on the Democratic ticket. Numerous political commentators of the left and right have caught wind of it and scoffed at it publicly. But it persists. Why it persists is an interesting question, the answer to which depends on how charitable you wish to be about the motives that drive Republican politics.

The cynical view is that a revanchist nationalist movement craves a political nemesis more threatening to them than Joe Biden. It’s hard to galvanize voters about the urgency of making America great again when the choice before them is between two elderly white men who grew up before the civil rights era reached full flower. It’s the Obamas, not Biden, who are avatars of the “new America”—especially Michelle, who represents not just racial change in American leadership but the growing political and economic power of women.

The less cynical view is that right-wingers are simply reacting rationally to the fact that Michelle Obama is a remarkably popular figure, much more so than Joe Biden. She routinely places in the top 10 of women whom Americans most admire and has finished first multiple times. Her memoir became the bestselling book of 2018 within 15 days of publication, moving millions of units. And for all the hype about how she disdains politics, she’s a talented retail messenger. Her speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention urging voters to “go high” when the other party “goes low” was more memorable than anything Hillary Clinton said that year.

Why wouldn’t Democrats want her to replace Biden? And why wouldn’t a movement as conspiratorial as the MAGA right believe there’s a secret plot afoot somewhere to make that happen?

Whichever theory you prefer, the common denominator is that the right finds it genuinely incredible that the president’s party intends to stick with a candidate who has become so weak. “Biden does often look and sound so enfeebled it’s hard to believe that a political party would really be pinning all its hopes—including purportedly saving American democracy—on him,” Rich Lowry marveled in a piece on the Michelle Obama scenario earlier this month.

I share their astonishment. Increasingly, so do left-leaning pundits.

Can Joe Biden actually win this election?

A Dispatch colleague pointed out to me this morning that this is the third straight presidential cycle in which Democrats have seemed more confident in their nominee’s chances than they should have.

In 2016 they took it for granted that Hillary Clinton would prevail over a disgraced game show host, so much so that the candidate herself never bothered to visit the swing state of Wisconsin. Democratic advisers rejoiced that God had answered their prayers (literally!) when Trump won the GOP nomination. Obama adviser David Plouffe predicted a worst-case scenario of 324 electoral votes for the first woman president.

Republicans ended up winning the White House and majorities in both chambers of Congress.

In 2020 the Democratic presidential field converged rapidly behind Joe Biden after he won the South Carolina primary despite his dismal performances in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada. Pandemic restrictions gave him the perfect excuse to campaign virtually from his home in Delaware, neutralizing his age and endurance as major campaign issues. Liberals anticipated a mass repudiation of Trump at the polls over his mishandling of COVID and his obnoxious daily antics.

Biden ended up winning by the skin of his teeth in battleground states and his party was routed in competitive House races.

Here we are again in 2024. Democrats seem oddly sanguine about letting their presidential wager ride on a nominee who’s considerably less popular and seems considerably more frail than he was during his first campaign. My colleague wondered if the party has developed a “blind spot” for frontrunners in its nominating process that’s left it unable to discern their electoral weaknesses.

There might be something to that. But in 2016 and 2020, the cause of the Democratic blind spot was straightforward and understandable: It was the polls that misled them.

Clinton led Trump comfortably for most of the campaign eight years ago, opening up a 7-point national advantage as late as three weeks before the election in the wake of the Access Hollywood scandal. Biden’s margins four years later were even gaudier: He finished 7.2 points ahead of Trump and had touched a 10-point lead in early October. Democrats were overconfident because, for complicated reasons, pollsters consistently underestimated Trump’s share of the vote.

This time is different. Democratic passivity toward Biden’s renomination is a product of paralysis in the face of incumbency and distressed denial that the American people might truly reelect a coup-plotting deviant after January 6. But I wouldn’t call that overconfidence. Look at the polls lately and you’ll find that it’s impossible to be confident, let alone overconfident, about the president’s chances in November.

Every month or so I check in with his numbers to see if there’s evidence yet of a backlash to Trump’s dominance of the early Republican primaries. For months, optimists I’ve theorized that swing voters who checked out of politics three years ago believing that Trump was gone for good will now start checking back in with alarm as they read news of him steamrolling his challengers for the GOP nomination. Inevitably, the polls will begin to shift toward Biden.

We’re now four primaries in. When does that shift begin?

Trump currently leads Biden by 2.1 points in the RealClearPolitics national average, about the same as he did in mid-November. In a three-way race with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., he leads by 4.3 points. In a five-way race, adding Cornel West and Jill Stein to the mix, he leads by 3.

The battleground polls are gruesome. It’s Trump by 1.2 points in Wisconsin, by 4.7 in Arizona, by 5.1 in Michigan, by 6.8 in Georgia, and by 8.4 in Nevada. Only in Pennsylvania does Biden lead, and in that case it’s by less than a point.

It’s not just one or two demographic groups that have shifted rightward since 2020 that account for Trump’s leads, either. Feast your eyes.

Some of the polls these averages are based on were conducted before the South Carolina primary, so it’s possible that swing voters who participated in them still hadn’t fully “awakened” yet to the reality that Trump will be the GOP nominee. But it must be stressed: The current averages represent deep holes for Biden, much deeper than they might seem.

Remember, he needed a 4.5-point win in the national popular vote in 2020 just to eke out narrow victories in decisive states like Georgia, Wisconsin, and Arizona. That means, if the current RCP averages are correct, he’ll likely need something like a 6-point shift in national polling before November to be reelected.

That’s an awfully ambitious ask for a candidate who hasn’t topped 45.4 percent in the head-to-head average against Trump in more than a year of polling.

And whose biggest policy liability, immigration, is now rated as the most important issue in the election among a plurality of voters.

And who trails his opponent by 22 points on the question of which candidate would handle the economy better.

And whom 86 percent say is too old to serve another term. That share is higher than the share of Americans who believe NASA landed on the moon in 1969, by the way.

How does Joe Biden orchestrate a 6-point shift with all of that weighing on him? At New York magazine, Jonathan Chait gazes into the abyss:

On the one hand, there are still ten months to go. The economy is in fantastic shape, and another almost-year of prosperity—along with, hopefully, an end to the war between Israel and Hamas—might give Biden a significant boost in the polls.

On the other hand, this is a way of saying that there needs to be a lot of positive development, with no major bad news, just to get into coin-flip territory. And while it is still somewhat early, the electorate is deeply polarized, and Biden and Trump are both unusually well-known figures. All that suggests there aren’t a lot of persuadable voters out there.

It’s true that the economy has become less of a liability for Biden than most of us expected a year ago. But it’s also true, as Nate Silver points out, that voters’ opinions of the economy have been brightening for months—yet there’s still no evidence of any shift toward the president in the polls.

Eight months out from Election Day, Trump’s enemies on the left and right are forced to face the terrifying fact that there’s little left that his opponent, the most powerful man in the world, can do to meaningfully increase his chances of victory. If Biden prevails, it’ll almost certainly be due to factors out of his control—some health issue that forces Trump from the race, a conviction in one of his criminal trials, a “hidden” anti-Trump vote among the electorate that all of the polls are somehow missing. When your best chance at victory depends on a deus ex machina, you’re in grave political trouble.

“It’s almost panic time” for Democrats, reads the subhead on Chait’s column. Almost?

Needless to say, Chait isn’t overconfident about Joe Biden’s chances this fall. Neither is Silver, who proposed an ultimatum: If Biden is unwilling to prove that he’s fit for command by doing a series of challenging interviews with serious non-friendly outlets (such as, for example, “a team of writers at The Dispatch”) then he should step aside as nominee. And no, Seth Meyers’ late-night show doesn’t count.

And if he does step aside, what should happen then? Ezra Klein, another decidedly not overconfident liberal, argued recently that Biden’s decision to end his reelection bid would free Democrats up to hold an old-fashioned open convention this summer at which party delegates would huddle and anoint a new standard-bearer against Trump this fall.

That probably would be the “cleanest” way of replacing Biden on the ticket, the least bad option available to liberals in a raft of terrible ones that begins with riding with the president all the way to November. But even the least bad option is plenty bad.

Start with what Klein gently describes as “the Kamala Harris problem.” Very simply, there’s no way to hold an open convention without insulting America’s first black, female vice president. She’s the nominee-in-waiting by dint of her position; she wouldn’t (or rather shouldn’t) have been placed on a national ticket to begin with if her party didn’t believe her fit to serve as its leader if necessary. Yet, to all appearances, she’s unelectable as a national candidate, polling below Biden and Trump in measures of favorability. She can’t be the nominee.

Democrats could and would strain mightily to atone to Harris’ admirers if she were snubbed at the convention. As Chait suggests, they might insist on a ticket featuring a woman and an African American—Gretchen Whitmer and Cory Booker, say, or Raphael Warnock and Amy Klobuchar—but the fact that a nominee-in-waiting who has both of those traits had been passed over would surely sting some members of the party’s loyal base of black women. That’s another reason why the Michelle Obama conspiracy theory endures among Republicans, of course: The former first lady is the only figure in the party who might plausibly solve “the Kamala Harris problem” singlehandedly.

Another problem is that lots of voters—including many Democrats—won’t share Klein’s vision of an open convention as a messy but exhilarating laboratory of democracy. Last week Ed Kilgore ventured down memory lane to the conventions of old and discovered that nominees who emerged from a contentious selection process, like Thomas Dewey and Adlai Stevenson, often lost the general election. And that makes sense: A nominee chosen by the party’s voters in the primary process enjoys democratic legitimacy, but a nominee chosen by shadowy party brokers at a convention is easily demagogued as a favorite child of corrupt insiders.

That critique would be especially potent given the enmity between neoliberal Democrats and progressives, the latter of whom have despised and distrusted the Democratic National Committee for years. Klein’s scenario imagines the end of an open convention as a sort of kumbaya moment for the left, united against Trump after resolving their differences. It would more likely be the case that one or more factions would come away irate over some real or imaginary backroom chicanery at their preferred candidate’s expense. There wouldn’t be much time for that rift to heal before Election Day.

Imagine a pro-Israel hawk narrowly defeating a pro-Palestinian dove in the delegate count—or vice versa, perhaps, after progressives inevitably applied intense pressure on the delegates to favor their agenda. The great virtue of an open convention in theory is that Democrats would be free to prioritize electability, anointing a nominee who compares favorably with Trump in terms of youth and centrism. But it might not work out that way in practice: There’s a chance they’d end up with a candidate with a few too many McGovernite tendencies to entice undecided swing voters.

The mere fact of dumping an incumbent president in favor of a candidate who’s unknown to most of the country would be so extraordinary and disorienting that it would strike many voters as a form of dirty pool, scaring them away from the new nominee. Trump and Biden are the ultimate political known commodities; replacing the latter at the last second with, say, the governor of Michigan would feed perceptions that the president’s candidacy had been a scam from the jump, a premeditated bait-and-switch. Voters would demand to know why, if he now believed he couldn’t serve effectively in a second term, he had bothered to run again in the first place.

Why hadn’t Democrats held a normal primary so that America could get to know their candidates? Why did they only seem to conclude that they needed a new nominee after the president began to trail Trump consistently in polling? Some might deem the gambit too cynical even for American politics in 2024 and resolve to hold it against Democrats at the polls.

All of these are serious concerns about an open convention. But there’s also a serious, compelling response: At this point, none of it matters.

If it’s true that Joe Biden can’t win the election absent a deus ex machina then he shouldn’t be the nominee. The party would be better off with anyone who might plausibly win without fate intervening, selected through whatever quasi-legitimate means are available. In the end, no matter who leads the Democratic ticket, the left’s argument will be the same: that this election isn’t a choice, it’s a referendum on whether a twice-impeached, four-times-indicted miscreant who tried to overthrow the government the last time he held office deserves to be trusted with that office again.

It would be painful to forfeit the advantage of incumbency in prosecuting that case, but having a no-name as nominee arguably makes it easier. Which match-up is more conducive to persuading voters that the election is a referendum on Trump: Trump vs. Biden or Trump vs. Random Generic Democrat?

Trump is the great Democratic unifier, a figure so repulsive that 81 million people were convinced in 2020 to cast ballots for an underwhelming, senescent establishment dinosaur in the name of defeating him. For all the anxiety about the hard feelings that snubbing Kamala Harris or holding a divisive open convention might create, party leaders might reasonably gamble that the specter of another Trump term would lead Democratic voters disgruntled by the nomination process to ultimately lay their grievances aside and come together behind a nominee who will, if elected, at least remain lucid during their term in office.

It’s not a great option or even a good one. It’s the least bad option available.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.