“Democracy is messy” is a cliché, but clichés become cliches because they’re true. Elections, debate, polling, cajoling, horse-trading, arm-twisting, and compromise, all punctuated by episodes of impasse and seasoned with heaps of grandstanding: It ain’t pretty to look at, but there’s no more civilized way to reconcile divergent public interests.

Democracy is also often messier abroad than it is here. If you think this week in Washington has been chaotic, may I direct your attention to the last six months of politics in the United Kingdom? Or the last four years in Israel?

That’s not to say that a messy delay in handling the people’s business is without costs. But America will survive a few days of legislative paralysis for the sake of gratifying Kevin McCarthy’s ego.

Besides, the standoff over the speakership could be good for American democracy writ large. I’ve written twice already this week about the virtues of returning to “regular order” in the House and won’t belabor the point here. But if you’re keen to see Congress function the way it’s supposed to, with members bargaining to arrive at a mutually satisfactory policy instead of the majority leadership descending from Mt. Sinai with a last-second omnibus bill etched in stone, you should be heartened by the Chip Roy faction winning procedural concessions from McCarthy.

This week in the House is what democracy looks like.

If you squint.

If you look at it straight on, it’s … fuzzier.

Which is why some of the “this is what democracy looks like” hand-waving from certain conservative commentators these last few days seems blithe and unserious.

Today is January 6. Radley Balko’s comment on Thursday night anticipating the occasion made me laugh.

It won’t surprise you to know, I trust, that more than half of McCarthy’s Republican opponents are election deniers and 14 of 15 who were members of Congress two years ago voted against certifying Joe Biden’s victory. The insurrection in the House this week against McCarthy consists mainly of insurrection apologists. It’s not a coincidence.

Nor is it a coincidence that McCarthy, eyeing the gavel in 2023, also voted against certifying Biden’s win and egged on election deniers during the “Stop the Steal” period.

When the time came for Congress to investigate January 6 and its precipitating causes, McCarthy signaled his contempt for accountability by naming two members who had voted against certification to the new committee. Nancy Pelosi understandably said no, not wanting coup supporters on a team charged with exposing a coup plot. Whereupon McCarthy withdrew his three remaining nominees in protest, the better to discredit whatever crimes the committee uncovered as products of a “partisan witch hunt.”

In short, an aspiring speaker who abetted a scheme to overturn democracy is begging for votes from a group that abetted a scheme to overturn a democracy in order to decide who’ll govern a House whose new majority abetted a scheme to overturn democracy. They’re all proud members of a party led to this day by the guy who hatched that scheme to overturn democracy. And whose governing committee felt moved to censure not those involved in the scheme to overturn democracy but those who sought to expose them.

Is that “what democracy looks like”?

Basic respect for democratic outcomes is the first trait I’d name if asked to describe what democracy looks like. None of the major players involved in what’s happening this week share that trait.

The second trait I’d name is a good faith attempt by all parties to compromise on policy. Sometimes compromise is impossible because key factions differ too sharply in their preferences. But an earnest attempt to get to yes is a basic requisite for a healthy system.

Is that what the current democratic standoff in the House “looks like”?

I quoted the Wall Street Journal’s assessment of the Gaetz/Boebert “Never Kevin” bloc in Thursday’s newsletter but it’s worth quoting again, as it’s all but universally shared by political observers. “The problem any GOP leader faces today is that too many Republicans don’t really want to hold and keep political power,” the editorial board wrote. “They’re much more comfortable in opposition in the minority, which is easier because no hard decisions or compromises are necessary. You can rage against ‘the swamp’ without having to do anything to change it. This is the fundamental and sorry truth behind the Speaker spectacle and the performative GOP politics of recent years.”

A system in which legislators are incentivized to paralyze the federal legislature for fame and fortune rather than legislate is not, I dare say, what real democracy looks like. Temporary obstruction while negotiating toward a desired policy end is democratic; chronic obstruction for the sake of seeming obstructionist is something else. “If you ask them what they want, they can’t articulate it,” Dan Crenshaw complained recently of the hardcore “Never Kevin” bloc. “If you go up to a lot of them right now they can’t tell you.” The insurrection of January 6, 2021, has little in common with the “insurrection” of January 6, 2023, but seeking glory in rebellion against an entrenched “establishment” is one common thread. As I said on Wednesday, the current GOP is really two parties disguised as one. And one of those has little interest in compromising with the other to govern.

Which, again, is not what democracy traditionally looks like.

“What about the Chip Roy faction?” you might say. The hardline “Never Kevin” bloc composed of Matt Gaetz, Lauren Boebert, and others might be implacable obstructionists but figures like Roy have withheld their votes to pressure McCarthy to make procedural concessions on returning to “regular order.”

That sort of temporary obstruction toward a meaningful policy goal is indeed what democracy looks like. And it paid off this afternoon: On the 12th ballot for speaker, Roy and 13 other Republicans who had opposed McCarthy in earlier rounds rewarded him for his concessions with their votes. He’s close to winning a majority now thanks to good old-fashioned horse-trading. The Gaetz insurrectionist bloc turned out to be small—although, as I write this, still large enough to be decisive.

What I wonder is whether the procedural concessions made to Roy, while good in theory, will be good for democracy in practice.

After all, one reason (although not the only reason) the House has moved away from “regular order” in modern times is because Republican leaders don’t trust their insurrectionist wing not to do something reckless with the procedural leverage they’ve acquired. Congress narrowly avoided a default on America’s sovereign debt during Obama’s presidency when the Tea Party Republican House majority tried to hold the debt ceiling hostage for spending cuts. The right wing of the new House majority is spoiling for another showdown over the debt ceiling, and this time it’s not just the performance artists who are eager for it.

McCarthy’s concessions to Roy will give the Freedom Caucus greater control over which legislation reaches the floor and the ability to offer poison-pill amendments designed to derail compromise bills aimed at averting a crisis. That could lead to horse-trading and more fiscally conservative outcomes, which would be a good thing. But having watched this party in action for the last decade, knowing the political pressure Republican politicians face to demonstrate that they’re “fighters,” is that the result you’d bet on?

This is the result I’d bet on.

Some Republicans might try earnestly in good faith to reach a deal with Democrats on the debt ceiling. But some will quietly conclude that the country needs a fiscal crisis to jar it from its complacency about spending. Some will reason that a crisis will benefit Republicans electorally since it’s the president who tends to take the blame for economic pain. Others will go the Gaetz/Boebert route of rebelling for the sake of rebellion.

Democratic government is messy, but it shouldn’t be so messy that it’s incapable of governing responsibly. Triggering a near-term fiscal calamity by refusing to raise the debt ceiling in hopes of extracting spending concessions aimed at preventing a long-term fiscal calamity seems like something less than a victory for democracy.

It may be “what democracy looks like” in point of fact. But if the new Congress can’t stop itself from steering deliberately off a cliff, we should probably restrain ourselves in celebrating the lovely democratic messiness playing out at the Capitol this week.

There’s blame to go around for the McCarthy embarrassment. He bears blame for being a jelly-spined opportunist who’s sold his soul many times over in the name of becoming the weakest speaker in modern American history. The Gaetz “Never Kevin” bloc bears blame for prioritizing grandstanding over good government. The bulk of the Republican caucus bears blame for not doing everything possible to pressure the Gaetz wing to capitulate, up to and including contemplating a deal with Democrats.

But amid the fingerpointing, there’s one party that’s escaped blame. It’s the one that always escapes blame in democracies even though it’s the one that’s most at fault in this fiasco. Jonathan Last knows. It’s the voters.

[T]his performative governing is what Republican voters want.

Not all Republican voters, of course. But a lot of them. Certainly enough of them to make what we are seeing completely predictable.

These are the Republican voters who suddenly care about the debt ceiling when a Democrat is president. Who get warm imagining that Donald Trump built The Wall. Who approve of their senators and congressmen voting against the certification of the 2020 election. Who stomp around and bitch about government spending as it’s being voted on—and then get all excited about the things their governors can do with the money the were against.

What we’ve seen in the House this week won’t end with the election of a speaker.

Let me repeat my own point from Wednesday’s newsletter explaining why the Gaetz bloc feels free to operate the way it does: “Parties are capable of imposing discipline on their members. The Republican Party isn’t capable of imposing meaningful discipline on the ‘Never Kevins.’… They can fundraise lavishly online without institutional party support, they can speak directly to voters without institutional media support, and they can trust that the GOP leadership won’t dare penalize them for fear of inciting a populist backlash. If the leadership did penalize them, it would only burnish their anti-establishment credentials and risk making them more popular. They’re functionally independents. And because their voters will continue to pull the lever for them as the ‘craziest SOBs in the race,’ they’re untouchable.”

The only entity in Republican politics capable of reining in Matt Gaetz is the voters in his district. Do you know how Gaetz fared last year in elections despite having spent most of the prior congressional term facing allegations of sex trafficking underaged girls?

He won the general election with more than 67 percent of the vote. He won his primary with more than 68 percent. Word on the street is that he’s looking at running for governor of Florida in 2026. He’s already one of the best known Republicans in the House, a mainstay of populist media. After his standoff with McCarthy, I expect he’ll be even more ubiquitous.

Republican voters aren’t going to rein him in. If anything, the “game show” feedback loop between conservative platforms and conservative audiences makes Gaetz a safer bet for reelection now than he was before. He’s a talented performer in a party whose voters value nothing so highly as theatrical contempt for their enemies.

That’s what democracy looks like to Republican voters now.

And no one understands that better than House moderates, the one elected entity capable in theory of neutralizing the Gaetz wing. Moderates could have reached out to Democrats this week to explore a bipartisan deal on a compromise speaker; a center-right “fusion” choice would have empowered the middle and been attractive to voters in swing districts. If nothing else, that sort of muscle-flexing would have dragged McCarthy back toward the center and stopped him (or any potential alternative candidate) from giving away the farm to the “Never Kevin” wing. But the moderates didn’t dare, knowing what it would have meant for their own primaries in 2024. Gaetz is a near-lock to be back in Congress next term despite having made a mockery of the speaker race with his weird vendetta against McCarthy. But a moderate who dared to approach liberals in hopes of sidelining the most nihilistic populists in Congress?

They’d be updating their résumé .

On Thursday, moderate Republican Brian Fitzpatrick assured CNN that his wing has the numbers to raise the debt ceiling when the time comes. A few centrist GOPers will join with Democrats to issue a discharge petition if need be, he insisted, forcing McCarthy to put a bill on the floor. Which sounds nice, until you remember who’s in charge here.

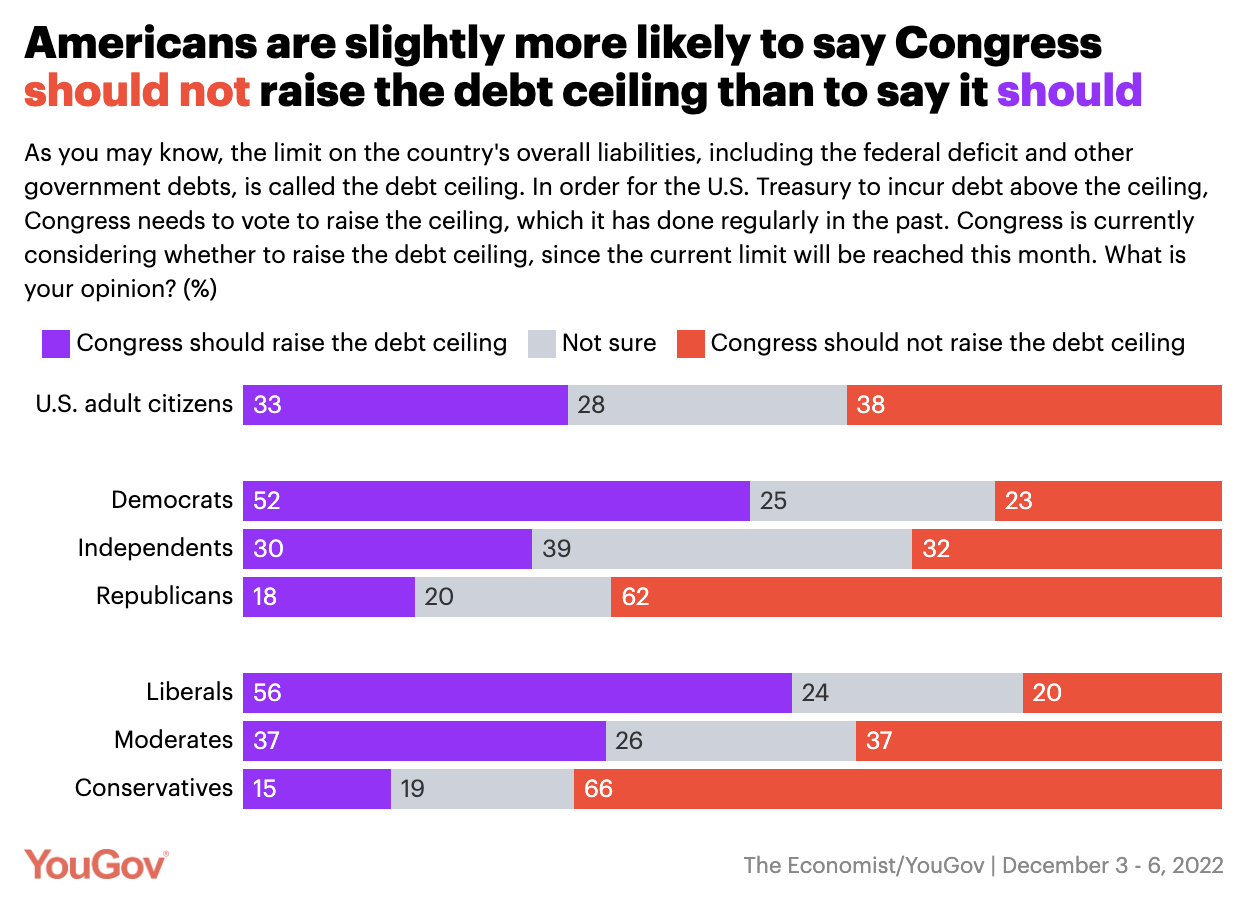

Republican voters are -44 on raising the debt ceiling, never mind the catastrophic fiscal consequences. Matt Gaetz will spend the eventual congressional debate on the subject screaming his lungs out against raising it before every microphone within a thousand yards of him. Who’s going to tell him no when he does? Brian Fitzpatrick?

If so, why didn’t he tell Gaetz no this week?

This is a party that now lacks all means of effective discipline against its least responsible actors. Trump can’t do it, McCarthy can’t do it, moderates can’t do it, conservative media can’t do it, all because the priorities of Republican voters have been warped beyond civic recognition by decades of terrible politicians and even more terrible commentators. In 2023, this is what democracy looks like. We deserve what we get.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.