An immutable law of American media is that today’s Republican villain is tomorrow’s exemplar of Republican virtue. Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Mitt Romney all saw their reputations redeemed to a degree among liberals once they were no longer a threat to win the presidency, the better to indict some emerging threat. “The same will happen with Trump,” many conservatives will tell you. “Just watch. If DeSantis is the nominee in 2024, the press will spend six months telling us he’s the scariest Republican yet.”

One reason that law persists is, well, it’s sort of true. From Reagan to Bush/Romney and then to Trump does illustrate a meaningful decline in the quality of Republican leadership and a transition from more libertarian-minded conservatism to “business lobby” conservatism to authoritarianism. And Reagan, Bush, and Romney each really did look better on the merits over time. The Cold War ended with American victory shortly after Reagan left office. Bush eschewed the bitter partisan rancor of the Obama years and profited from the contrast in personalities with Trump. Romney behaved courageously by twice supporting Trump’s impeachment and has tried to legislate creatively as a senator. The media’s rehabilitation of old right-wing demons isn’t always a cynical scheme to damn the latest right-wing demon by comparison.

But thinking that whoever follows a twice-impeached coup-plotter as Republican nominee might be worse than he was? That’s pretty cynical.

On Monday Vanity Fair columnist Bess Levin published a piece titled “A Comprehensive Guide to Why a Ron DeSantis Presidency Would Be as Terrifying as a Trump One.” It wasn’t an argument for preferring Trump to DeSantis; the former guy “should be legally prohibited from coming within 1,000 feet of the Oval Office and it would clearly be a boon for humanity if he was never heard from or seen again,” Levin wrote. But it was an argument that DeSantis “would be no better” as president than Trump was, a recommendation of remaining agnostic given a choice between the two.

I am not agnostic. Nor should you be if asked to choose between a candidate who hasn’t tried to wreck American democracy and one who has.

But Levin’s column about DeSantis’ record as governor does hit on a strange wrinkle of the coming presidential primary. For the first time as a candidate, Trump might not be “the craziest son of a b-tch in the race.” That phrase comes from a memorable interview Rep. Thomas Massie gave in 2017 explaining why so many Ron Paul voters in the 2012 primaries ended up becoming Donald Trump supporters in 2016. An authoritarian candidate should struggle to attract libertarians, but Trump didn’t. Massie knew why.

“I went to Iowa twice and came back with [Ron Paul]. I was with him at every event for the last three days in Iowa,” Massie said. “From what I observed, not just in Iowa but also in Kentucky, up close with individuals, was that the people that voted for me in Kentucky, and the people who had voted for Rand Paul in Iowa several years before, were now voting for Trump. In fact, the people that voted for Rand in a primary in Kentucky were preferring Trump.”

“All this time,” Massie explained, “I thought they were voting for libertarian Republicans. But after some soul searching I realized when they voted for Rand and Ron and me in these primaries, they weren’t voting for libertarian ideas — they were voting for the craziest son of a b-tch in the race. And Donald Trump won best in class, as we had up until he came along.”

It’s rare for an ideologue to minimize the importance of ideology in electoral victories but Massie’s conclusion is inescapable. Trump was closer to being the least libertarian candidate in the field in 2016 than the most libertarian, but as a brash political newcomer vowing to disrupt business as usual in Washington and willing to say anything in the process, he was assuredly the most unpredictable—the “craziest.” A primary voter keen to go on offense against Democrats and underwhelmed by the willingness and ability of establishment Republicans to do so might understandably have preferred a loose cannon.

The mystery of the next primary is whether Trump’s disordered personality—sorry, “unpredictability”—is enough for him to retain the title of “craziest SOB in the race” or if voters will measure craziness in terms of each candidate’s relative ardor in prosecuting the culture war against the left. Are sheer pugnaciousness and amorality the hallmarks of a good “fighter” or does a track record of victory in cultural battles like DeSantis’ mean more?

I ask because, amid all of his usual screeching about rigged elections and terminating the Constitution, lately Trump has begun to sound a bit more … moderate. At least by the standards of modern Republican populists.

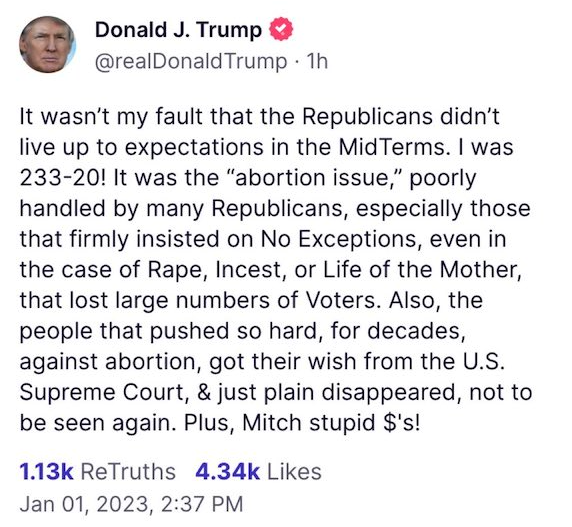

By the standards of MAGA dogma, this post from a few days ago practically qualifies as progressive. It rocked conservative social media as it made the rounds.

There’s a grain of truth—but only a grain—buried beneath the B.S., as Ramesh Ponnuru has explained. Some strict “no exceptions” candidates like Tudor Dixon and Doug Mastriano fared badly in November, but incumbents like Mike DeWine and Brian Kemp who signed “heartbeat bills” into law did well. Texas’ trigger ban prohibits abortion in all cases except for life-threatening medical emergencies and Greg Abbott won by double digits. And some ardently pro-life Republican candidates like Blake Masters and Herschel Walker did inch away from strict bans as the campaign wore on to try to woo pro-choice independents. Moderating on abortion was no guarantee of victory and holding firm on abortion was no guarantee of defeat.

There’s no reason to think pro-life voters “disappeared” either. Republicans turned out in droves in November, typically at a higher rate than Democrats did. The GOP lost tight races because a small but meaningful share of their coalition crossed over to support Democratic candidates over Trump-backed election cranks.

All of that being so, pro-lifers didn’t care to see him try to pass the buck for November’s failures.

“Trump blames pro-lifers, the most loyal voting bloc the Republican Party has had for more than 40 years, for the disappointing midterms,” Steve Deace of BlazeTV marveled. “This is self-immolation in real time.” Others took the familiar path of excoriating Trump’s staff for not intervening to prevent the great man from posting nonsense instead of excoriating the great man himself for posting it. Josh Barro noted trenchantly that Trump’s great sin, even more than supporting exceptions to abortion bans, was his tone in treating pro-lifers as foreign to his own beliefs: “‘The people’ who wanted Roe overturned ‘got their wish’ and then ‘disappeared.’ Doesn’t he count himself as one of those people who wished for Roe to be overturned?”

It’s strange for a politician who relies so heavily on “us and them” demagoguery to suggest to a core part of his base that he might be more “them” than “us” on the ultimate culture-war flashpoint.

But he went further in an interview with Breitbart.

“Now, I think a lot of Republicans didn’t handle the abortion question properly,” Trump told Breitbart News. “I think if you don’t have the three exceptions, it’s almost impossible in most parts of the country to win. If you don’t have three exceptions—I said to a very nice man running for governor of Pennsylvania, ‘If you don’t have the three exceptions, you can’t win.’ Same thing with Tudor. She didn’t have the three exceptions. I say this to the Republican Party: If you don’t have the three exceptions, because you know the Democrats are radical and they’ll kill the baby at nine months or they’ll kill the baby after the baby is born. Okay? That’s more radical. But, you know a 15 or 16 week period of time, but you have to have the three exceptions. If you don’t have the three exceptions, you’re destined to doom.”

A 15-week ban might be the “sweet spot” of what the average swing voter prefers in regulating abortion, but it’s not sweet to the sort of committed pro-lifers who vote in Republican primaries. The most prominent example of a red state with a comparatively lax 15-week ban is Florida and Ron DeSantis has gotten an earful about it from anti-abortion activists. With Roe finally off the books, with states like Texas imposing total bans and Georgia and Ohio passing six-week bans, why is a state governed by the MAGA heir apparent lagging so far behind?

The answer, clearly, is that DeSantis feared a backlash at the polls in November if Florida Republicans had passed something more draconian before the election. Now that he’s been sworn in for another term, he’s promising to atone by signing a six-week ban after all. There was, in other words, a strategic calculation behind DeSantis’ temporary embrace of a 15-week ban. What’s the strategic calculation behind Trump’s?

Is he going to run to the center on abortion—in a Republican primary? When every other candidate on stage will be touting strict bans or six-week bans as evidence of their willingness to “fight” the left?

What kind of “fighter” is that?

It would be newsy if Trump’s only heresies against the base lately were limited to the topic of abortion. But they aren’t.

On vaccines, too, he’s stuck with a “moderate” position.

Trump is anti-mandate but remains pro-vaccine at last check, justifiably proud of his administration’s achievement in bringing the shots to market so quickly via Operation Warp Speed. DeSantis followed the populist herd, however, by drifting from anti-mandate to something more recognizably anti-vaccine. Here, too, his strategic calculation was obvious: He’s grasping for ways to get to Trump’s right in the upcoming primary and saw vaccine politics as a way to do it. It’s unbearably cynical, but if you’re keen to show Trump cultists that you’re more MAGA than even the Great MAGA King, vice-signaling over the vaccines is one way to do it.

How about Tuesday’s big news, Kevin McCarthy’s pitiful bid to wrangle the votes needed to become speaker? Most Republican politicians outside Washington are lying low on the matter, seeing no benefit to involving themselves needlessly in a bitter party squabble. Not Trump, though. He’s been lobbying behind the scenes in hopes of softening opposition to his preferred candidate. But his candidate isn’t a populist favorite like Jim Jordan, Andy Biggs, or Matt Gaetz. It’s McCarthy. Here again, given a choice between joining a fight against the establishment or joining the establishment itself, Trump sided with the latter and pitted himself against the most pugnacious members of his own camp.

The fact that the Gaetzes and Lauren Boeberts in the caucus felt empowered to ignore him and oppose McCarthy anyway is evidence of his declining clout post-midterm. Trump’s position is no longer the proper populist position ex cathedra. Not when he’s siding with the moderates, in any case.

There’s another way in which Trump has shown moderation recently. In the same Breitbart interview, he was asked about rumors that Republicans might seek to reform entitlements the next time they control all of the federal government. “We’re not cutting Social Security,” he vowed. “It’s very simple. It’s a simple answer. We’re not cutting Social Security. … We have to protect it. It’s a contract with the people. They go in. They work and they do. They put their blood, sweat, and tears into Social Security and then you have a guy like a Paul Ryan or others that want to destroy it.”

That sort of moderation isn’t new for him. His reluctance to slash Medicare and Social Security as a candidate in 2016 distinguished him from traditional Republicans’ push for austerity during the Tea Party era. (Then again, he also promised to eliminate the national debt as president if elected to two terms.) But there remain many Republicans who believe, correctly, that America’s current entitlement scheme is unsustainable and urgently needs reform before a fiscal crisis strikes. Some are members of Congress and are preparing to have a showdown with Democrats on the subject when it comes time to raise the debt ceiling.

Here too, in other words, Trump will be aligned with liberals against right-wingers who are spoiling for a fight over an unaffordable welfare state.

Finally there’s Ukraine, where Trump hasn’t taken a moderate position so much as no position at all. Another guy named Donald Trump has been vocal in vilifying Volodymyr Zelensky and MAGA populists in the House like Gaetz and Marjorie Taylor Greene have led the nascent right-wing effort to block funding the next time it comes to the floor. But Trump Sr. has kept a low profile on the matter, again leaving space on his right in the coming primary for an opportunist like DeSantis to attack him for being noncommittal. If “America First” means America first, DeSantis might say, why has the nominal leader of the America First movement declined to take a strong stance against sending tens of billions of taxpayer dollars abroad to fight Russia?

Trump’s relative silence on that subject might now be changing. But even this criticism posted on Monday is less a shot at Ukraine than at NATO for forcing the U.S. to once again bear most of the financial load for Western defense.

In the abstract, each of the “moderate” stances Trump has taken is understandable. They’re all popular positions among the general public, after all. “No exceptions” bans on abortion are disfavored even among Republican voters. Most of the U.S. population has been vaccinated for COVID and support for entitlement programs remains strong. Although right-wing enthusiasm for backing Ukraine has faded, a majority of the electorate continues to favor providing weapons. And as for McCarthy, while I doubt most Americans have strong feelings about him becoming speaker, I suspect the average joe prefers that the new Congress get to work as soon as possible. Less chaos, more legislating: That’s the core argument for sticking with McCarthy, the current leader of the Republican caucus. And it’s likely what most voters prefer.

For a normal politician leading a normal party, then, all of those stances would be forgivable in the name of electability. But a party where the “craziest son of a b-tch in the race” tends to win isn’t a normal party. The modern GOP is a vehicle for performative culture war and Trump’s modest scolding about abortion, the vaccines, the welfare state, and RINO all-stars like McCarthy are destined to lead some supporters to wonder if he’s still the most aggressive culture warrior in the field.

Which is a bad spot for him to be in, since he also happens to be the least electable candidate in the field. If DeSantis can play the part of uncompromising “fighter” more authentically than Trump can and can very plausibly argue that he’s more likely to win a national election than Trump is, what’s the case for Trump?

Lord knows, his modest moderation on a few issues isn’t going to win over many swing voters if he’s nominated again. Once you try to stage a coup and fail, you’ve given up your claim to being the “sensible” electable choice on the ballot in the general election.

And besides, Trump didn’t take any of his “moderate” positions to try to make himself more appealing to the center. He took them for the same reason he does everything, out of narrow self-interest. He’s scapegoating pro-lifers for the midterm results to shift blame away from himself for the disappointing outcome. (As Ponnuru notes, when making endorsements, Trump seemed not to care whether Republican candidates took a radical line on abortion so long as they echoed his election lies.) He’s pro-vaccine because Operation Warp Speed gives him something to boast about. He’s pro-McCarthy because McCarthy has been a loyal toady, slavishly seeking Trump’s favor in his bid for power. And he’s pro-Ukraine—or at least not loudly anti-Ukraine—because he doesn’t like to associate with losers. And we all know which side in that war is losing.

All of this is beside the point, though. Whatever his motives, Trump has left space to his right for ambitious rivals to attack him for having lost some of his MAGA mojo. Mike Pence could smack him for being an abortion squish, weakening Trump’s evangelical support. DeSantis will come at him on the vaccines to pander to the ivermectin junkies. Some fiscal conservative will run the numbers and remind him that nondiscretionary spending is a math problem that can’t be solved as-is, especially with interest rates rising.

The takeaway for some Republican voters in 2024 will be that we can and should choose a “fighter” next time who’s more committed to the fight. Having helped turn the party into an endless series of populist purity litmus tests over the last six years, Trump may find that even he can’t pass the test anymore.

And if he can’t, that’s when things might get really interesting.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.