Dear Capitolisters,

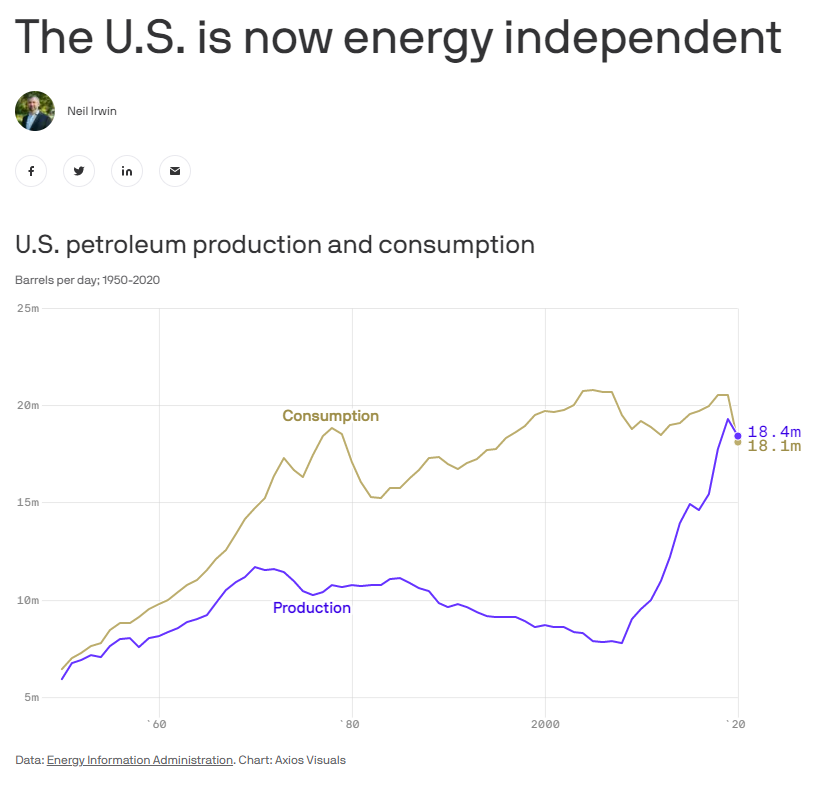

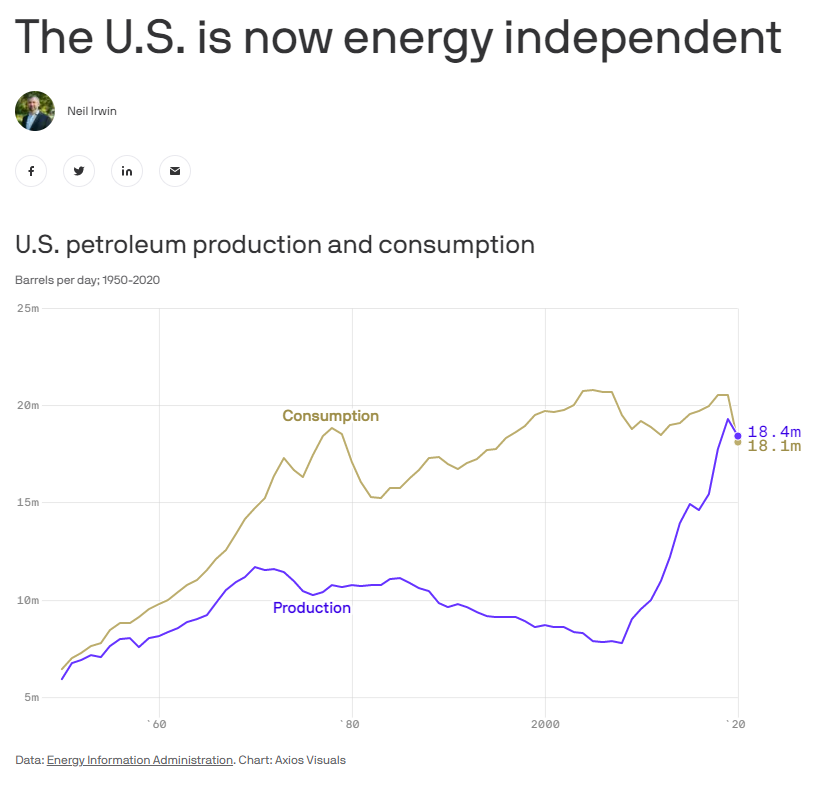

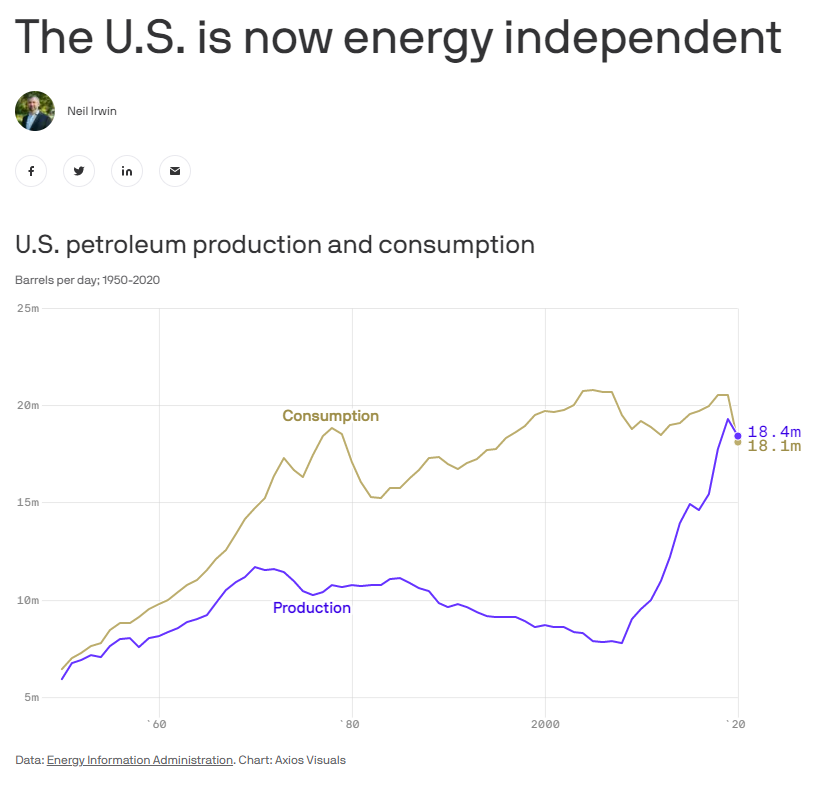

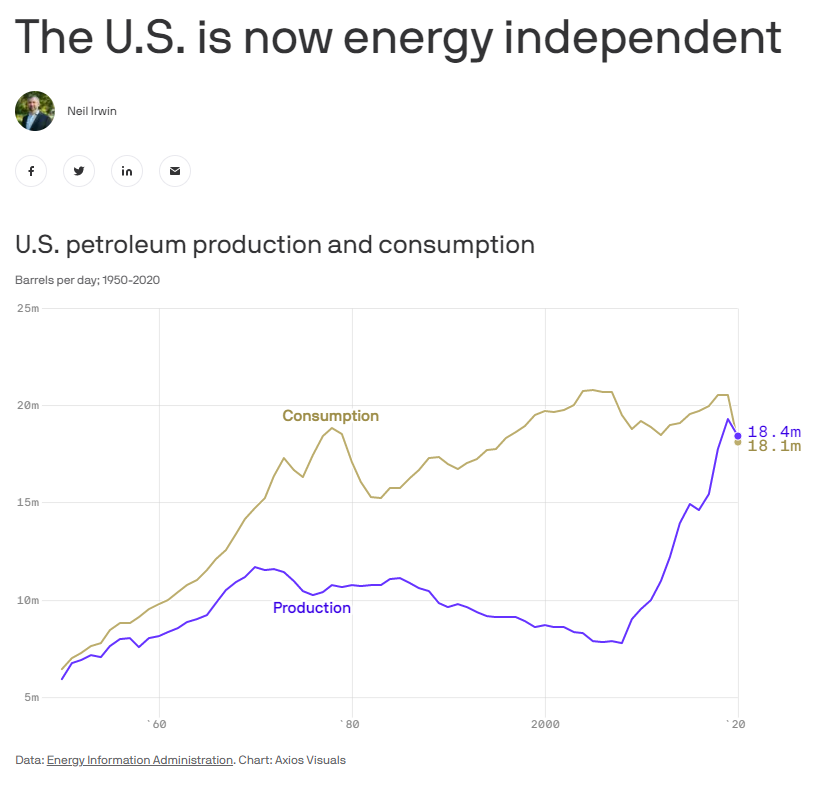

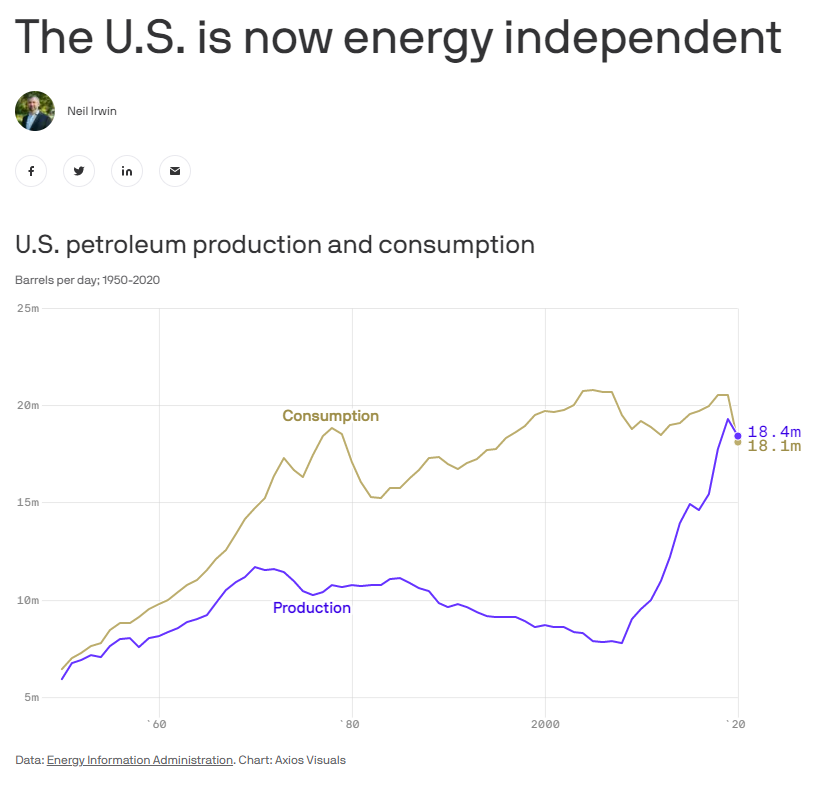

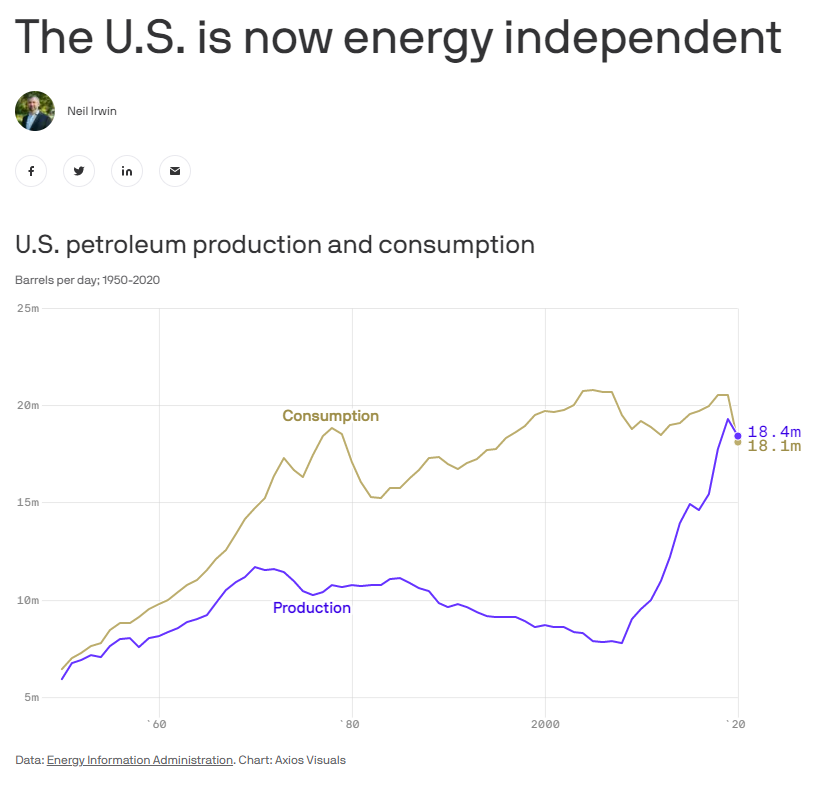

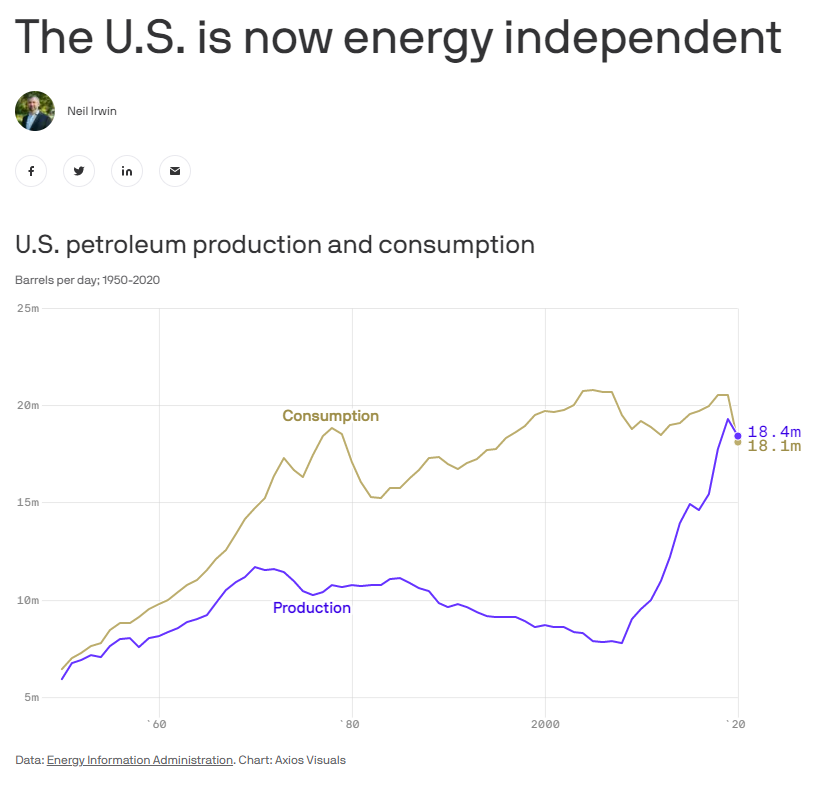

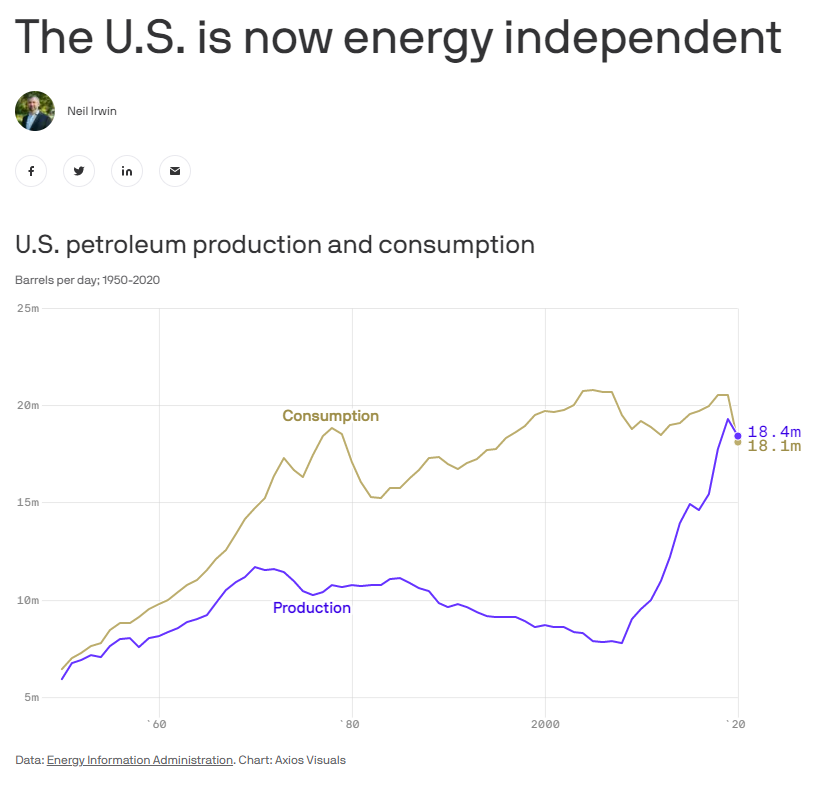

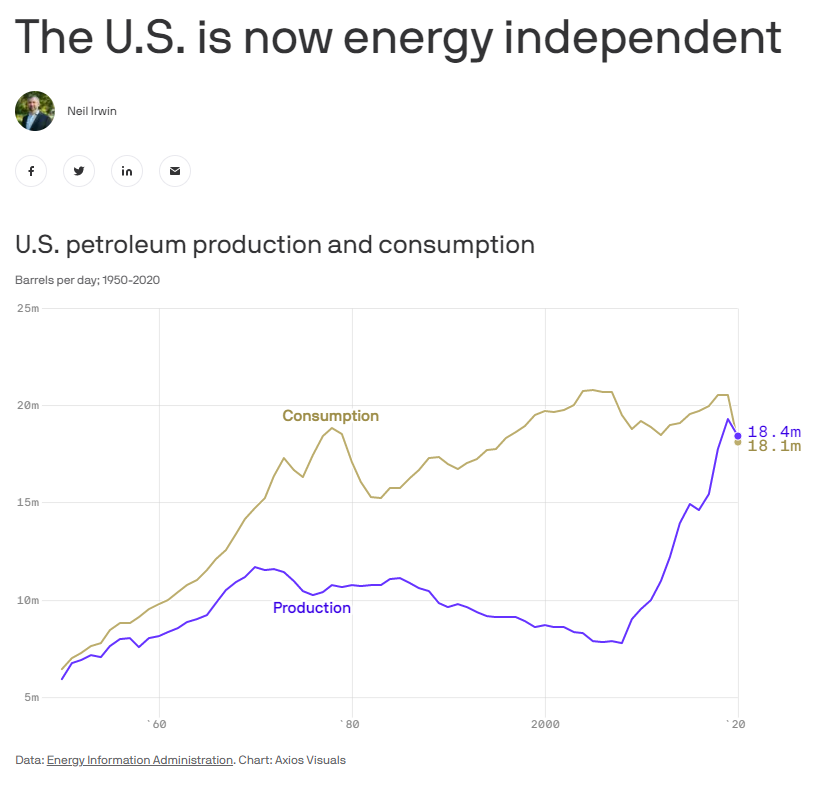

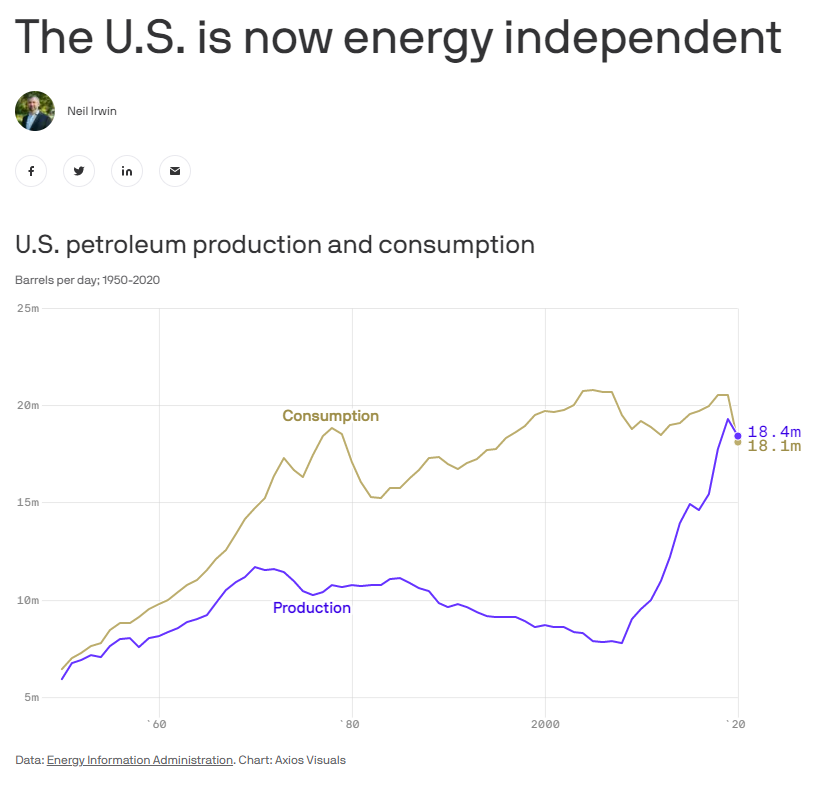

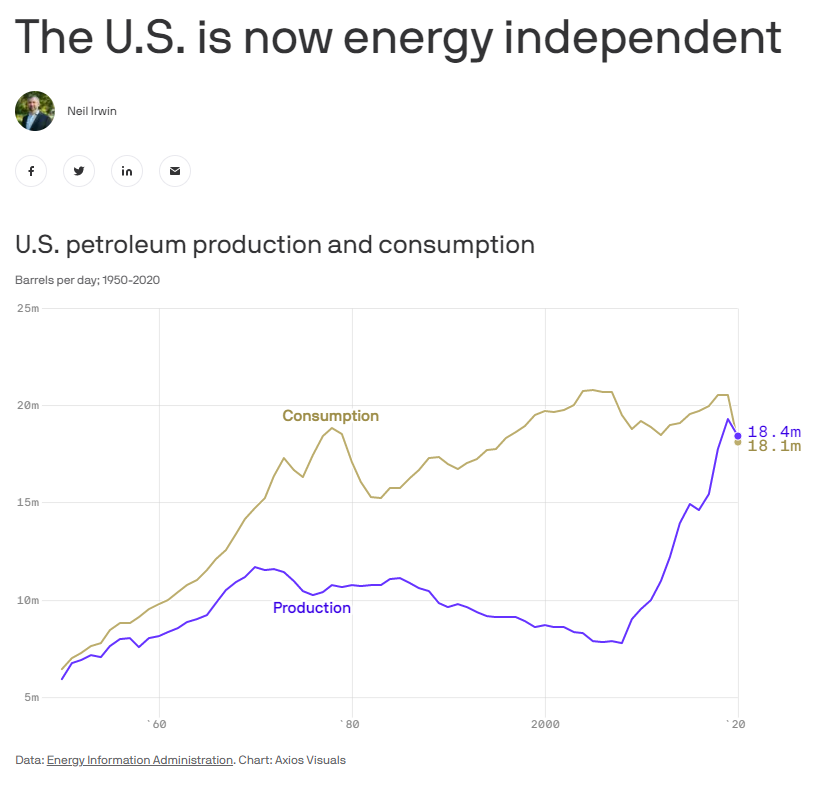

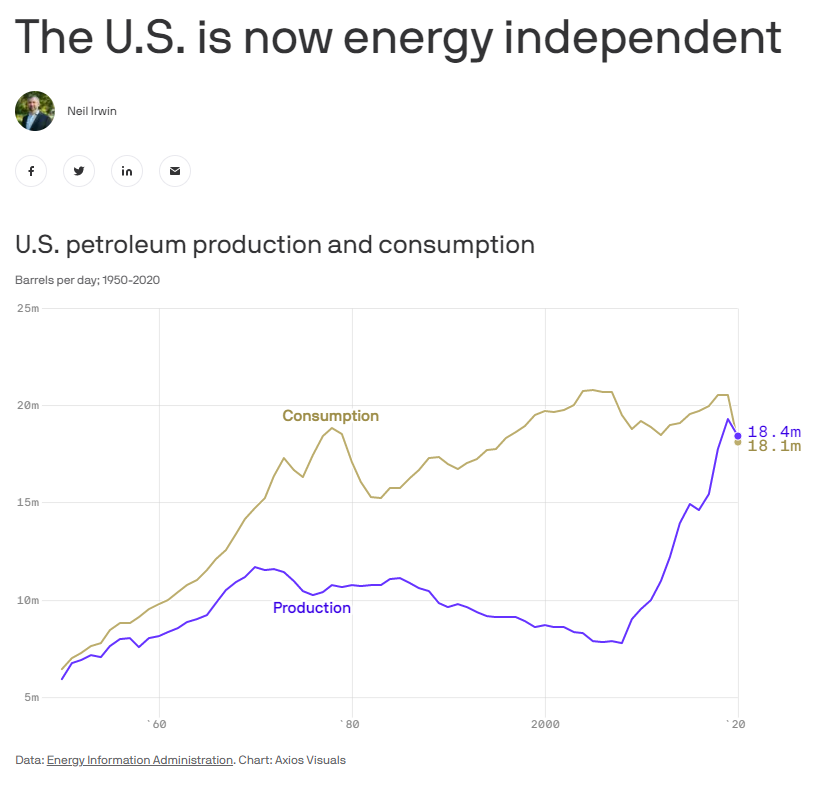

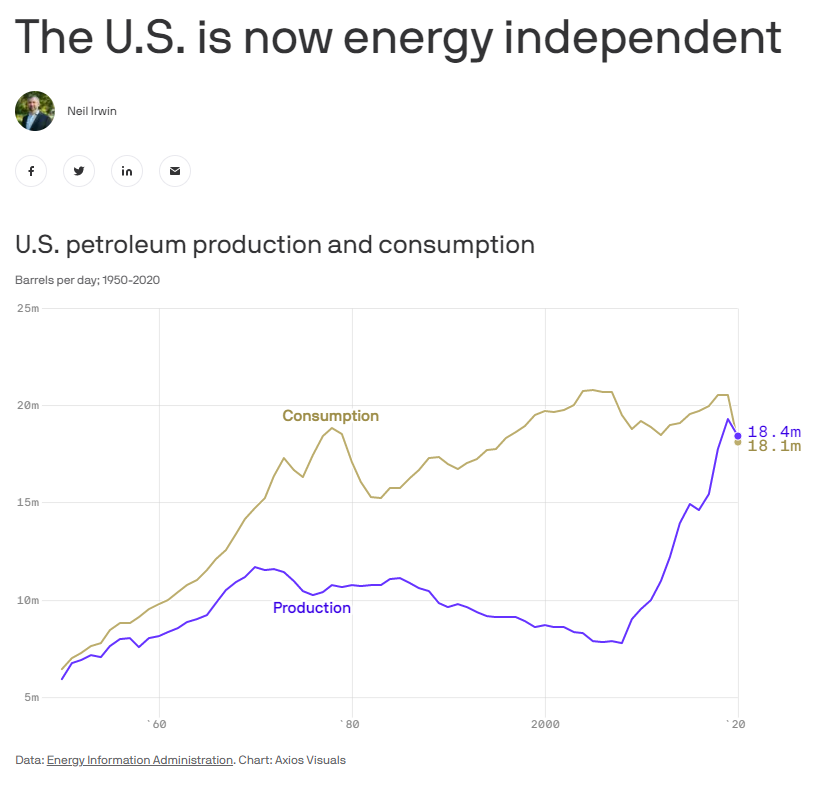

After last week’s deep dive into supply chains, recent events give us a great real-world example of the benefits of economic openness and the costs of isolationism. (So pardon me in advance for covering some of the same stuff two weeks in a row.) In particular, the following chart and headline—increasingly relevant given Ukraine, global energy markets, and your local gas station—caught my attention last week, though less for what it said and more for what it didn’t.

On the former issue, it’s hardly big news that the “shale revolution” here dramatically changed domestic and global oil markets, with the United States taking over the global lead in the production of both crude oil and other liquid petroleum products like gasoline and diesel:

As the first Axios chart shows, by 2020 the total volumes of U.S. petroleum products production and consumption were basically even, and, following decades of talk about “energy independence” and stuff, that may very well be a big deal… politically.

In reality, however, the topline data hide several important lessons about global energy trade, comparative advantage, and real, long-term economic “resiliency”—lessons that much of Washington, as recent debates on supply chains and globalization show, seems to have forgotten.

A Global Power in a Global Market

For starters, the United States is not only a massive producer of petroleum products—liquids and gas (via pipelines and LNG)—but also a massive importer and exporter of these same goods:

Today, the U.S. imports much more crude oil from Canada than anywhere else—more than four times (approximately 1.37 billion barrels a year) as much in 2021 as all OPEC countries combined (290 million barrels):

Canada is also the top supplier of natural gas to the United States, almost entirely via pipeline, and the United States is on pace to be the world’s top exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG) in 2022. We also send a good bit of piped gas to Canada and Mexico too (though less than LNG these days).

Heading down the value chain, the United States is a huge exporter of refined petroleum products, and we also import a lot of those, too, from dozens of countries around the world:

(Both charts are random samples of top trading partners; go to the link to explore the data yourself.)

But Why Trade?

So why does the United States—a true global energy powerhouse with some of the best refineries in the world and several large consumer industries (e.g., petrochemicals) too—trade so much energy? A few reasons:

Most obviously, additional production capacity needs to make economic sense from an investment perspective. This is a big issue right now, as U.S. oil producers and their investors got burned by the oil price collapses in 2015 and 2020, and some remain hesitant about going nuts now—especially given that high global oil prices could be relatively temporary. (Yes, policy matters too, but the lack of price predictability/stability in today’s market very likely matters more.) Where U.S. demand (consumption) outstrips domestic refinery capacity (as it often still does), we can import the difference from a wide variety of sources.

Second, there’s the issue of refineries. For example, North America’s biggest refinery—Motiva’s Port Arthur, Texas, facility—is owned by Saudi oil giant Saudi Aramco and imports crude from its overseas affiliate. (Total oil imports from Saudi Arabia, however, are low by historical standards.) Also, and as numerous commentators have noted recently, many U.S. refineries were built before the shale boom and remain optimized to process different (heavier) oils than the lighter stuff than comes from much of the United States. This last point is particularly an issue for a few refiners on the Gulf Coast, which have been importing Russian feedstocks ever since U.S. sanctions on Venezuela effectively banned that heavy crude from the market. For those refineries, an easy American substitute isn’t available. As the Wall Street Journal explains:

There are two ways in which a ban on Russian imports hurts refiners. It hurts margins because refiners will be looking for replacement barrels in an already-tight crude market. Commercial U.S. crude oil inventories are about 12% below the five-year average for this time of the year. Stockpiles are low among other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development group too. This means U.S. refiners will need to outbid other eager buyers in the market. Secondly, changing the type of crude oil going through the refining system makes it less productive. “If there were better crude [oil grades] out there before, refiners probably would have been running them,” notes Matthew Blair, equity analyst at TPH.

Since refiners are trying to optimize production to keep prices competitive (low), they avoid oil that doesn’t allow for that.

Third, there are logistics (infrastructure, storage, and transport) issues. Inventories, for example, act as a cushion for supply-demand imbalances, supplementing or removing supplies as needed, but are of course limited by physical capacity constraints. Petroleum products also need ships, pipelines, trucks, trains, and related facilities to be transported around the country or the world, and this can affect trade flows. Sometimes, this is just a matter of availability or geography—transporting liquids across the Rocky Mountains by rail, for example, isn’t cheap or easy, so West Coast refiners often rely on imports of light crude that’s also produced in the United States. Other times, however, it’s regulatory: Oil and gas pipelines and LNG export terminals, for example, are subject to lengthy, often burdensome reviews. And, of course, the Jones Act makes transporting crude, refined products, and natural gas (LNG) from the Gulf to certain U.S. destinations cost-prohibitive, so these consumers buy from foreigners instead, while U.S. refineries export the same products elsewhere. As the EIA explains:

Because of logistical, regulatory, and quality considerations, exporting some petroleum is the most economical way to meet the market’s needs. For example, refiners in the U.S. Gulf Coast region frequently find that it makes economic sense to export some of their gasoline to Mexico rather than shipping it to the U.S. East Coast because lower cost gasoline imports from Europe may be available to the East Coast.

Finally, there’s just good ol’ comparative advantage at play: Certain countries are better at making certain types of petroleum products than others, so they often specialize in those goods and then trade for the rest. Mexico provides a good example: We’ve long imported crude from Mexico and then exported refined products back to them, even though the United States has an absolute advantage over Mexico in making both crude and products. But trade still makes economic sense, because both sides will come out ahead by focusing more on what they do best. (High five, David Ricardo!)

Put this all together, and you get a U.S. petroleum market satisfied by domestic production, imports, and exports—as this cool EIA graphic for liquids helpfully demonstrates:

First, the Bad News

These dynamics offer bad news and good for the U.S. energy market and American consumers. On the bad, you get a domestic energy market that can’t be quickly “fixed” in times of global crisis (pandemic, war, etc.) For example, because oil is a globally traded commodity with few major barriers to trade (in normal times), the prices of liquid petroleum products—mainly oil, gasoline, and feedstocks—are determined on global markets: Prices generally rise when worldwide demand outstrips supply and fall when that dynamic reverses. (The aforementioned factors, especially logistics stuff, can affect local prices a little, but this is the general rule.) Thus, we see the global (Brent) crude price and the U.S. (West Texas Intermediate, or “WTI”) price generally track each other over time, except for a short period in the 2010s when U.S. oil production was increasing rapidly but the United States prohibited almost all exports of crude oil. Once that export ban was lifted (more on that in a sec), the Brent-WTI spread mostly disappeared:

The pandemic has caused massive imbalances in global supply and demand over the last two years, with the unexpected collapse and then rebound in global oil demand meeting a less flexible global supply, and petroleum prices responding accordingly. In short, a lot of global dollars chased pandemic-crimped supplies, and oil prices rose. A lot.

These market dynamics affect global gasoline prices in a similar manner: As shown in the following chart from the World Bank, for example, price changes (not levels, which vary widely due to taxes) generally follow the same path over time:

This also means that domestic oil production is—for better or worse—pretty disconnected from domestic gasoline prices:

Bloomberg’s Justin Fox shows a similar (lack of) relationship between crude oil imports and gasoline prices:

Surely, U.S. production and policy can influence global (and domestic) prices over the medium- to long-term, but they can’t control it – especially not quickly. Or, as Rapidan Energy’s Bob McNally told CNN last week:

What Americans and US officials really care about is the price of gasoline, and that has almost nothing to do about whether we’re energy independent or not… Can the US wall itself off from volatility in the global oil market? The answer is “no.”

But Plenty More Good News

This rather disappointing conclusion might lead some to suggest that the United States would have been better off if we limited trade (imports and exports) and embraced isolationism instead. But, even leaving aside that prices in isolated energy markets (for example, the United States’ natural gas market in the early 2010s before we had substantial LNG export capacity online) still generally track global prices, there is plenty of evidence that “energy autarky” would make things worse, not better for U.S. producers, consumers, and broader national interests.

First, economic isolation would exacerbate domestic economic shocks. We covered this generally just last week, but the U.S. energy market provides a real-world lesson every time a major hurricane hits the Gulf of Mexico (where a lot of U.S. energy production is located). Then, domestic petroleum supplies taken offline by storm-related shutdowns are rapidly replaced by imports, leaving the U.S. market generally stable overall. (See, for example, Hurricane Ida in 2021 and the role financial traders play in this “market calming” process.)

Second, isolation can actually discourage domestic production. For starters, refiners benefit from unfettered access to cheap feedstocks from around the world—feedstocks that often are supplied (in optimal form, at least) by only foreign producers. Limit that access, and these companies decrease production or pass on their higher costs to American consumers.

Export restrictions, meanwhile, can also hurt—as I explained in a 2013 paper advocating a removal of our outdated and restrictive U.S. licensing systems for crude oil and natural gas exports:

[B]y depressing domestic prices and subjecting export approval to government discretion, the U.S. licensing systems retard domestic energy production, discourage investment in the oil and gas sectors, and destabilize the domestic energy market. Artificially low prices prevent producers from achieving a sustainable rate of return on the massive up-front costs required to drill and extract oil and gas, and investors lack any assurances under the discretionary licensing systems that domestic prices will not collapse when output increases. In fact, recent low domestic gas prices caused many U.S. energy companies to sell assets and shutter new projects. These same concerns affect the domestic crude oil market and have led the IEA to warn that the current export restrictions have put the “American oil boom” at risk.

According to the EIA report commissioned by DOE, increased natural gas exports would lead to higher prices followed by increased domestic production. But prices are not expected to skyrocket, and consumers will continue to benefit from hypercompetitive fuel and feedstock supplies. Independent reports from the Brookings Institution and Deloitte project that permitting gas exports would lead to a small and gradual increase in domestic natural gas prices. Such predictability and consistency is good for the industry and the overall stability of the U.S. energy market—it would prevent boom and bust cycles of high/low prices and high/low production that hurt the U.S. economy and prevent companies from implementing long-term investment, production, and hiring strategies. The current situation—in which oil and gas export decisions are left the whims of federal regulators—has the opposite effect.

The crude oil export ban was finally lifted in late 2015, and LNG export approvals were accelerated about the same time. Several subsequent analyses have since confirmed that domestic prices rose only a little, that the restrictions had indeed deterred domestic investment and production in the United States, and that these and other distortions gradually disappeared once exports were liberalized. The result: a stronger U.S. industry and more robust and efficient domestic and global petroleum markets. And little (if any) serious consumer harm.

By contrast, restricting exports—which some are again advocating today to benefit American consumers—would eventually hurt that very same group. As the Dallas Fed recently explained:

One important point this proposal overlooks is that the prices of gasoline and diesel in the United States are determined by their prices in global markets since the U.S. trades diesel and gasoline. Because a cessation of U.S. crude oil exports would lower the supply of oil in global markets and raise its price, one would expect global fuel prices, if anything, to increase as a result. Refiners can always sell these fuels abroad at their global price, so it makes no sense for them to sell for less in the domestic market.

In other words, the prices of gasoline and diesel fuel in the U.S. would not be expected to decline and might actually increase, rendering the crude oil export ban not only ineffective, but also counterproductive. Thus, there is no reason to expect that U.S. consumers would benefit from such a ban.

Banning crude exports, however, would benefit refiners of light sweet crude in the short run because they can buy crude oil that otherwise would have been exported at a discount, while selling fuels at high global prices.… The short-run bonanza for U.S. refiners specialized in refining light sweet crude, however, would not last. As the price of domestically produced crude oil declines and storage fills, it would not be long before some domestic oil producers become unprofitable and cease operations.

Similar problems arise with another government scheme recently floated—using the WWII-era Defense Production Act to mandate additional U.S. oil and gas production. Any short-term gains would not only be costly for taxpayers, but be more than offset by longer-term pains for the domestic industry and American consumers.

Finally, efforts to micromanage U.S. and global energy markets would surely generate broader economic and geopolitical harms. As the Trump “trade wars” and early days of the pandemic taught us (when medical goods export restrictions temporarily proliferated), for example, U.S. trade restrictions would likely breed foreign copycats, as short-term political or economic factors pushed other governments to respond in-kind. Mandates, meanwhile, could produce supply gluts (and eventual cuts). Either way, the result would be even more instability and even less investment/production (except, perhaps, for state-owned producers abroad that lack typical market incentives!), leaving almost everyone worse off in the long run.

Meanwhile, the last few weeks have demonstrated why having a robust domestic energy industry and liberalized trade regime, driven mainly by market forces, is in the broader national interest. Europe, for example, was a top destination for U.S. LNG exports in the months leading up to the Russian invasion, as high prices there attracted American sellers. Without a strong profit motive to sell gas abroad (where prices tend to be higher) and long-ago regulatory approvals, the U.S. production and infrastructure needed to facilitate those sales wouldn’t have existed. Government planners couldn’t just flip a switch last year. At the same time, the diverse, global trading system for energy will (eventually) allow sanctioned Russian petroleum imports to be offset by some combination of domestic production and other imports. And the U.S. economy is richer—and thus more resilient overall in the face of the current global shocks—because of the economic growth that previous, efficiency-maximizing energy transactions helped foment. No need to copy “Fortress Russia.”

(Just in case the last few weeks haven’t already made that clear.)

What Real Reform Looks Like

Of course, there certainly are U.S. policies that could be reformed to improve domestic and global energy abundance—in petroleum and other, non-oil energies. But, as Stand Together’s Adam Millsap just explained in depth, most of these moves don’t involve Rube-Goldbergian schemes to subsidize, mandate, or tax our way to energy autarky but instead simply getting the government out of private parties’ way and letting the market work—repealing the Jones Act (which also discourages offshore wind); streamlining regulatory approvals (especially environmental ones); reducing construction and permitting costs; facilitating interstate communication and planning; eliminating restrictions on imports of finished energy goods like hydropower or solar panels and key inputs like pipeline steel, electrical transformers, and wind towers; and generally adopting a “permissionless” standard for new energy technologies.

That’s a recipe for real American “energy independence”—regardless of the energy’s source or destination.

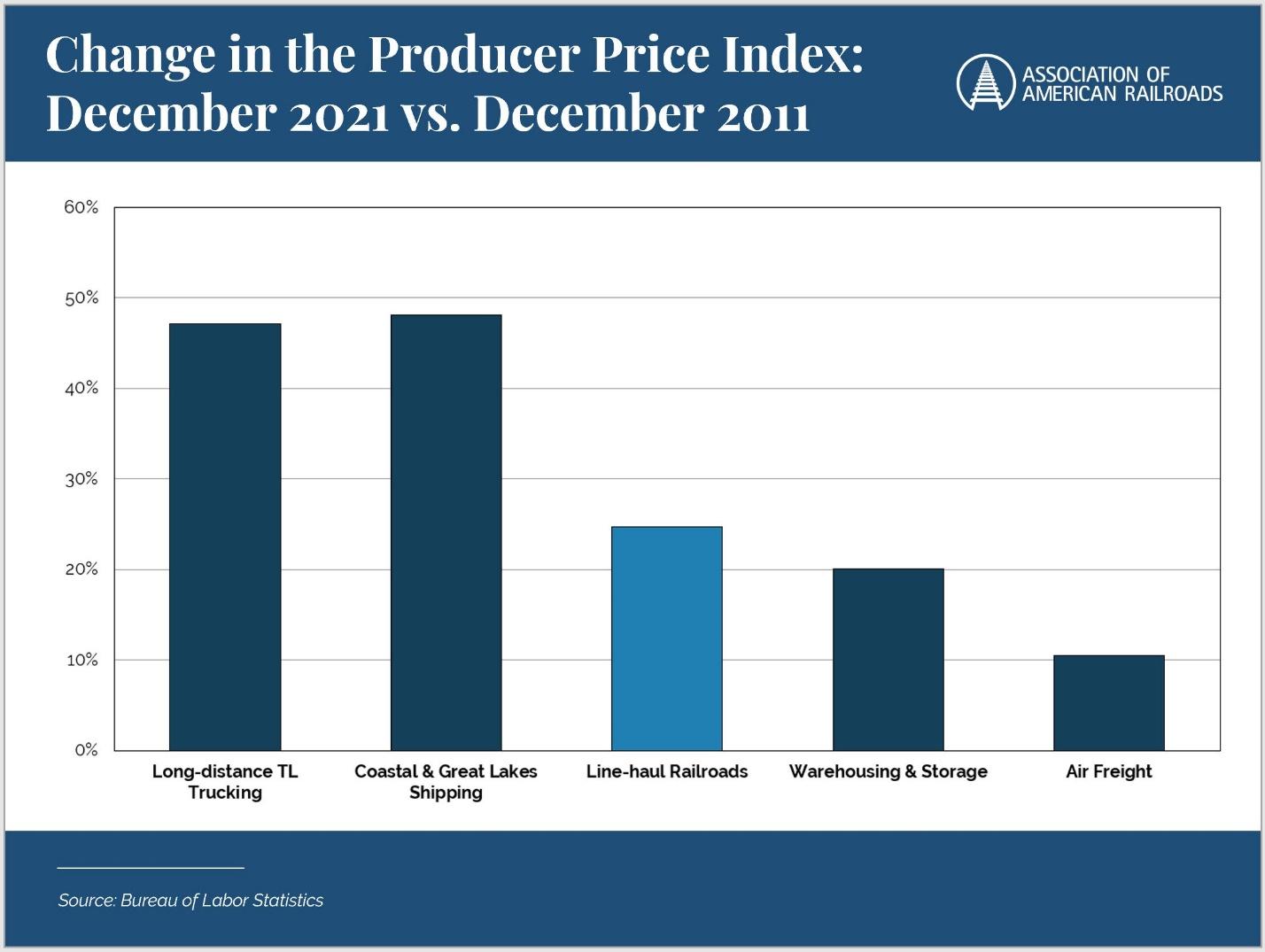

Chart(s) of the Week

Bonus Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.