Dear Capitolisters,

I hope you all had a wonderful Independence Day weekend, full of grilling and exploding stuff. I surely did. Anyway, right before the break, I participated in an event on whether and to what extent the United States would continue implementing economic nationalism and isolationism for the next few years. Spoiler: We all agreed that it would, given the current view among the leadership of both major political parties that a rejection of past trade liberalization was necessary for both political and economic reasons. (Hey, don’t shoot the messenger.)

On the economic point in particular, the conventional wisdom in Washington—and seemingly a rare area of bipartisan consensus—is that free trade, trade agreements, and globalization have been great for wealthier Americans and the nation overall, but a a raw deal for the American working class, and therefore a major contributor to economic inequality in the United States. And so to reverse these trends (or, at least, to look like we’re trying to reverse them), economic nationalism—tariffs, industrial policy, “Buy American” rules, and most definitely no new trade agreements—are on tap for the foreseeable future. As one recent book put it, Trade Wars Are Class Wars so that’s what we’re getting.

Free traders often counter this particular claim by noting* that, while foreign competition undoubtedly disrupts certain lower-income American workers (particularly in less-skilled manufacturing industries like textiles), these same individuals also disproportionately benefit from lower prices for basic necessities. Thus, the D.C. trade debate often devolves into a typical (and admittedly boring) “jobs versus consumables” choice, with advocates for each side predictably sticking to their preferred positions.

As usual, however, this framing is far too simplistic, and a fascinating new paper shows why—providing some broader lessons about trade and jobs along the way.

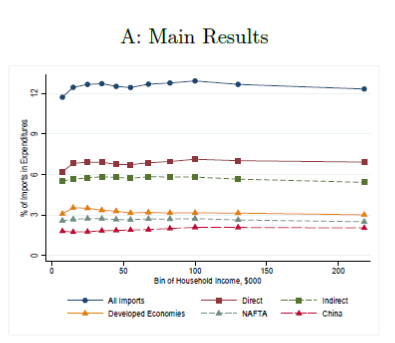

Americans’ Surprisingly Egalitarian Consumption of Imports

Using a novel, comprehensive dataset of actual U.S. consumer expenditures in 2007 (the height of “China shock” import competition and job displacement) for all goods and services, as well as additional “microdata” on consumer goods and motor vehicles, economists Kirill Borusyak and Xavier Jaravel examined how Americans—rich, poor and in between—actually consume imported goods and services, including the stuff (raw materials, parts, etc.) embedded in finished goods. They find—contra the conventional wisdom noted above—little variation in import consumption across all relevant income groups (i.e., from poor to rich Americans): overall, about 12.6 percent of Americans’ total annual spending is on foreign goods and services, and the difference among income groups is quite small (ranging from 11.7 percent to 12.9 percent).

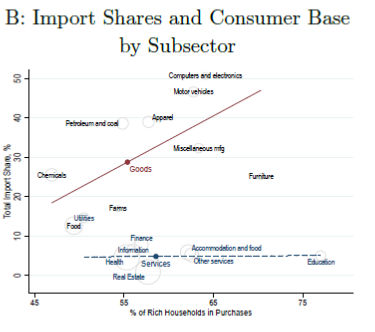

While this might seem surprising at first (it was to me), it makes more sense when you get into the weeds as the authors do: Poorer Americans surely spend more of their paychecks on goods (see this recent David Henderson discussion for more), but a lot of that consumption is food, which is mostly produced domestically. While richer and poorer Americans tend to buy the same stuff from abroad, moreover, we do so in different amounts, at different price points or levels of quality, with different shares of imported content, and from different places. As the authors put it, “subsectors with a high import share, such as Computers and Electronics, are purchased disproportionately more by high-income consumers, while subsectors without much imports, such as Food, are purchased relatively more by low-income groups.” And we all buy about the same low share of foreign services, which aren’t traded as much as goods but represent a large and growing share of our total consumption.

Thus, to put it simply: It all kinda evens out.

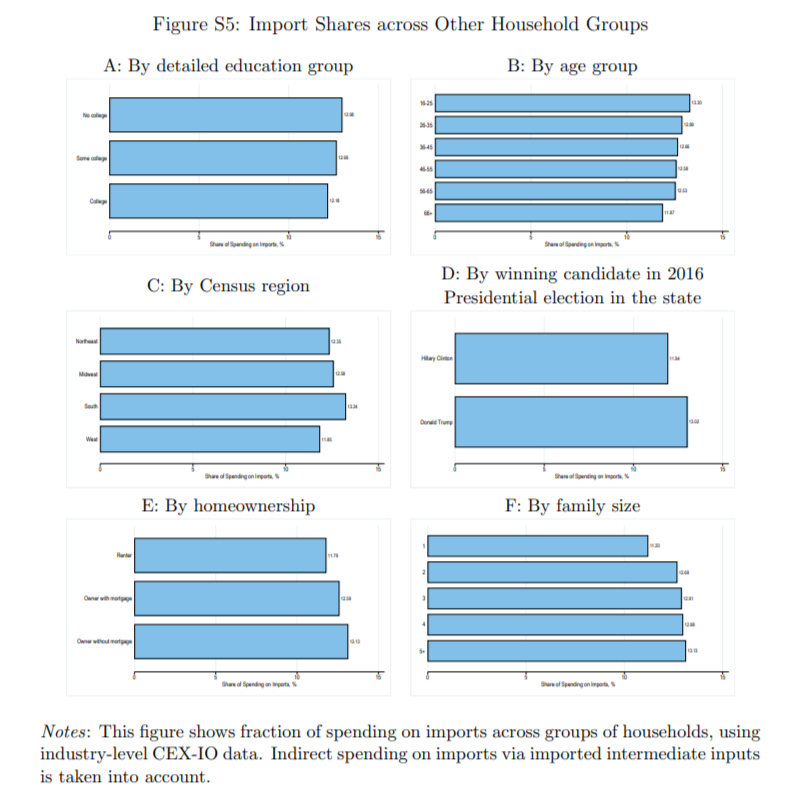

The egalitarian nature of Americans’ import consumption is particularly noteworthy across education and other demographic categories. For example, consumers in states that went for Trump in 2016 actually spent a little more on imports (13.02 percent) than states that went for Clinton (11.94 percent); non-college more than college; younger people more than older ones; large families more than singles; homeowners more than renters; and so on. But, again, these differences are small overall.

Import consumption is thus one of the few things on which all Americans seem to agree—whether we admit it (or like it) or not.

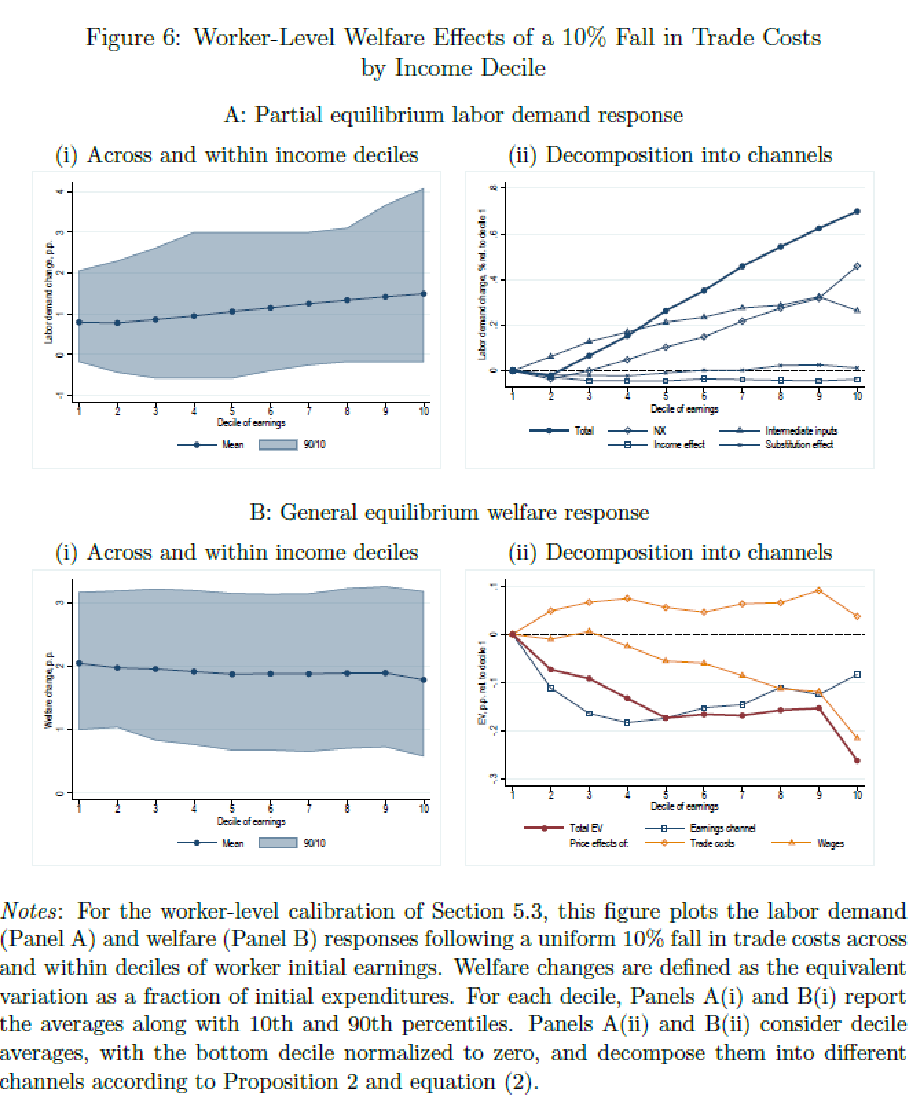

But the Jobs

The aforementioned findings are novel enough for a standalone paper, but the authors use them to make far more—in my opinion—important ones about trade and American jobs. In particular, they use their dataset to examine the distributional effects of several trade “shocks”—including a hypothetical 10 percent reduction in total U.S. trade costs, trade liberalization with China, and the “Trump tariffs” of 2018—via two different economic models: a “partial equilibrium” model focused on how trade liberalization affects demand for certain jobs (“labor demand”) and a “general equilibrium” (economy-wide) model that determines how several factors (for export opportunities, import competition, imported manufacturing inputs, income effects, and “substitution” effects) affect Americans’ overall welfare (i.e., their earnings and expenditures). They again find a surprisingly small amount of difference across income groups, with average welfare of Americans in each group gaining about 2 percent from a 10 percent decrease in trade costs. By contrast, they find larger differences for Americans with roughly the same incomes. In other words, two U.S. workers with the same incomes had much more varied experiences from trade liberalization than two average workers with different incomes. This is shown in the “(i)” charts below, with the solid line (difference across income groups) pretty flat but the gray band (difference within income groups) pretty wide

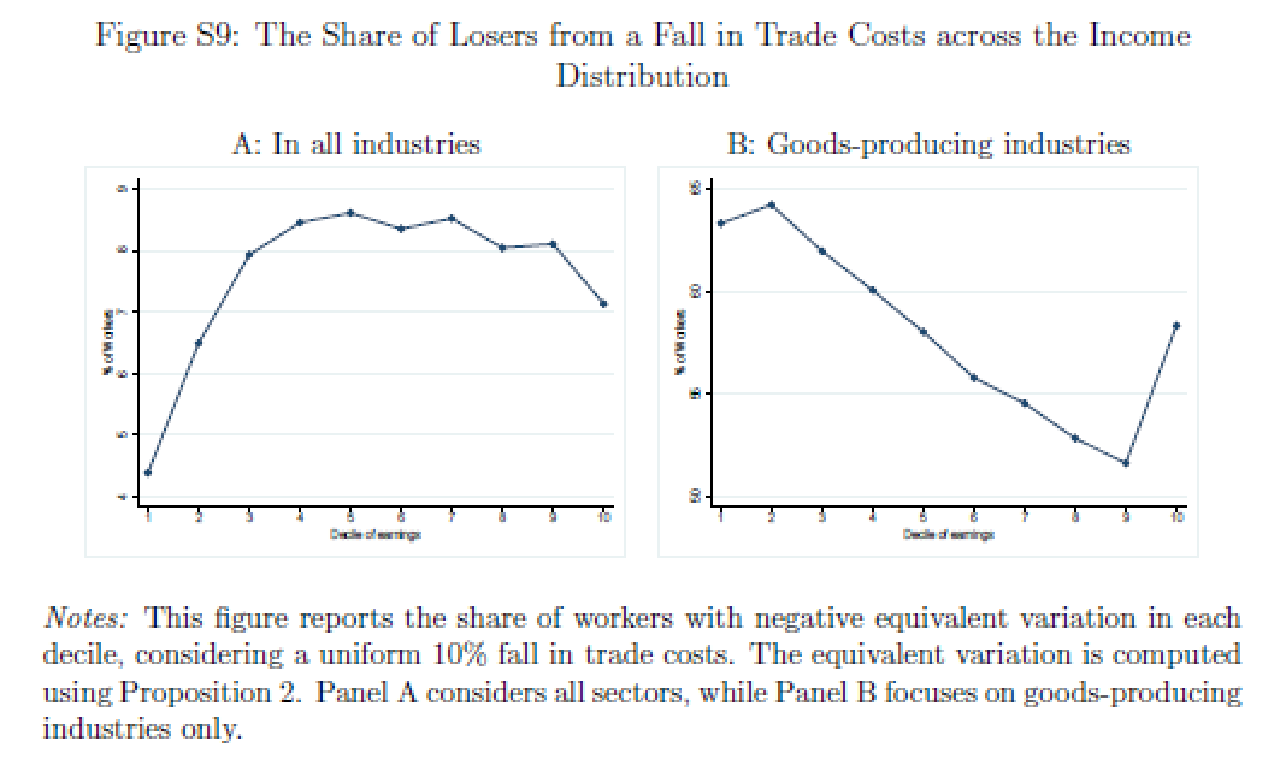

Of course, like pretty much all economic policies, not everybody comes out ahead: there are some “losers” who experience an overall decline in welfare immediately following a trade liberalization “shock.” However, these folks are a relatively small share (between 4.4 percent and 8.5 percent) of each income group. Meanwhile, more than 90 percent of Americans in all groups—poor, middle class, and rich—ended up better off following a decline in U.S. trade barriers:

So much for those “class wars,” eh?

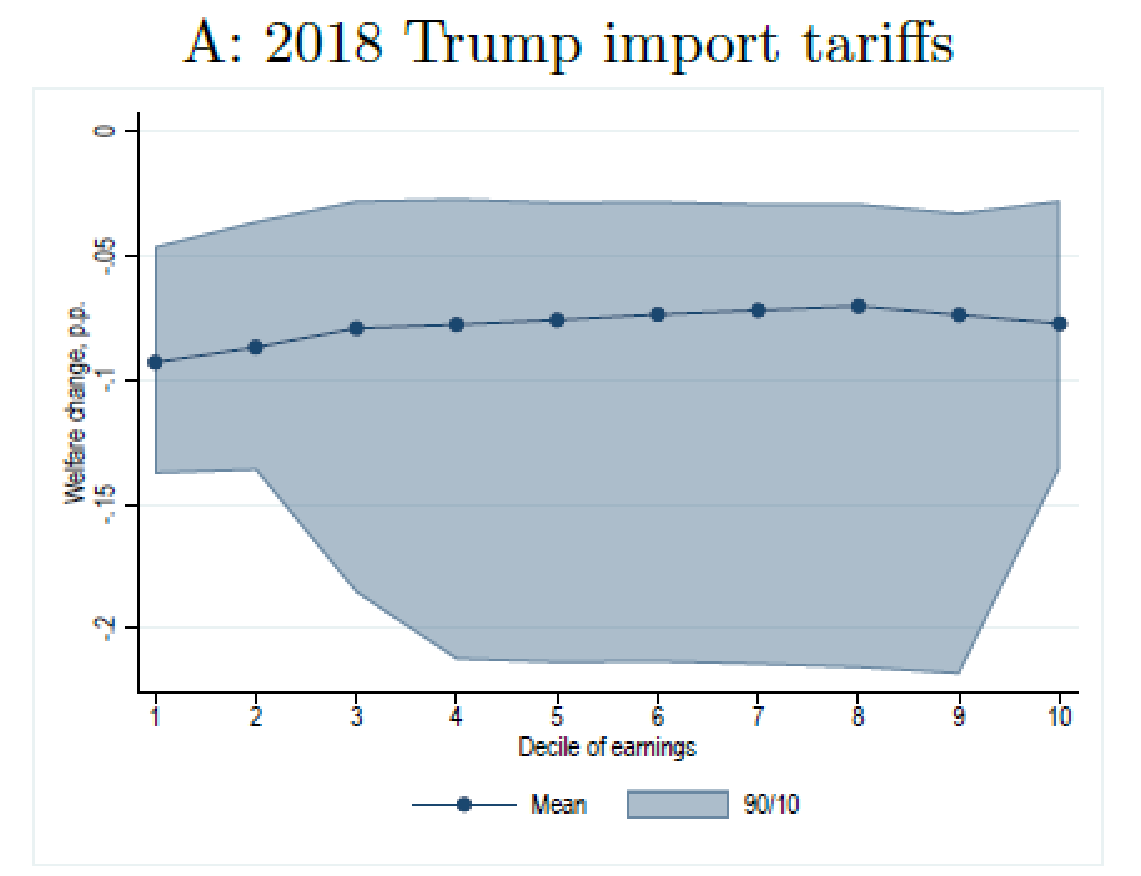

The authors find similar results across educational groups (non-college benefiting a little more than college, but insignificantly so); for a hypothetical reduction in barriers for imports from China, the NAFTA region (Canada/Mexico), and developed economies; and from actual declines in U.S. tariffs between 1992 and 2007. In each case, Americans benefit overall, and differences in gains are small across income groups but more significant within those same groups. Finally, they examine the “Trump tariffs” and find small average losses in welfare but—again—little variation across income groups. (Interestingly, the biggest losers in this case were Americans in the vaunted “middle class” and above.)

These findings again run counter to the conventional wisdom but—also again –make perfect sense once you consider how trade liberalization affects U.S. workers and the fields in which most Americans today work. In particular, the vast majority of us work in service industries that aren’t directly affected by trade in goods, which is where most trade occurs. Most of us thus experience trade “shocks” only as consumers or via macroeconomic forces affecting demand for our labor, while the relatively few Americans working mainly in manufacturing—a share of the U.S. workforce that’s been declining since the 1940s (and is, as we’ve discussed, happening everywhere)—also experience imports as competition. The following chart makes this difference clear, showing a little more than half of U.S. manufacturing workers “losing” from a hypothetical trade shock across income groups (the others presumably gaining from things like expanded export opportunities and cheaper imported inputs—see this new paper for more), but representing relatively few Americans overall (“all industries” in the first panel):

Because (again, contra the conventional wisdom) low- and middle-income jobs in the United States aren’t actually concentrated in manufacturing and are instead spread out across income groups (e.g., steelworkers and steel executives), most “working class” Americans experience—and most benefit from—trade liberalization just as wealthier ones do. Indeed, as the authors note, lower-income Americans might not benefit more than richer ones as consumers but could via the economic growth and dynamism that trade generates: “when labor demand grows, less traded industries, such as services, experience a larger increase in wages. Since services also have relatively more lower income workers, this larger wage response benefits the low-income group more.” And their data bear this out.

(It’s also worth noting here that, as Don Boudreaux explains in a new piece, even the “losers” can come out ahead in the longer run.)

Given these dynamics, the authors conclude that, because “the distributional effects of trade are mostly ‘horizontal’ (within income groups) rather than ‘vertical’ (across groups)… [o]ur findings run against a popular narrative that ‘trade wars are class wars.’” Indeed, they do.

But Those Manufacturing Jobs

This is, of course, only one paper (and I’m sure one could quibble with some details), but it does make a ton of sense, given what we already know about the changing U.S. workforce and American consumption patterns away from goods and toward services. Perhaps one might argue that the “class war” narrative remains valid in the sense that manufacturing jobs are uniquely valuable for working class Americans and thus merit protection despite these new findings, but—as I show at length in my new working paper on U.S. industrial policy –that rings hollow too. Leaving aside that manufacturing jobs have been declining as a share of developed nations’ workforces for decades, that U.S. manufacturing output remains solid, and that American incomes generally aren’t stagnant, we see that:

-

Manufacturing jobs are not significantly more stable or secure than jobs in other sectors—especially for low-skilled workers whose manufacturing jobs have been disappearing for decades and are most exposed to automation and trade. And although U.S. manufacturing jobs have increased since the Great Recession, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that the sector will resume its long-term trend of shedding manufacturing jobs (444,800 of them, to be exact) over the next decade because of international competition and productivity-enhancing technologies.

-

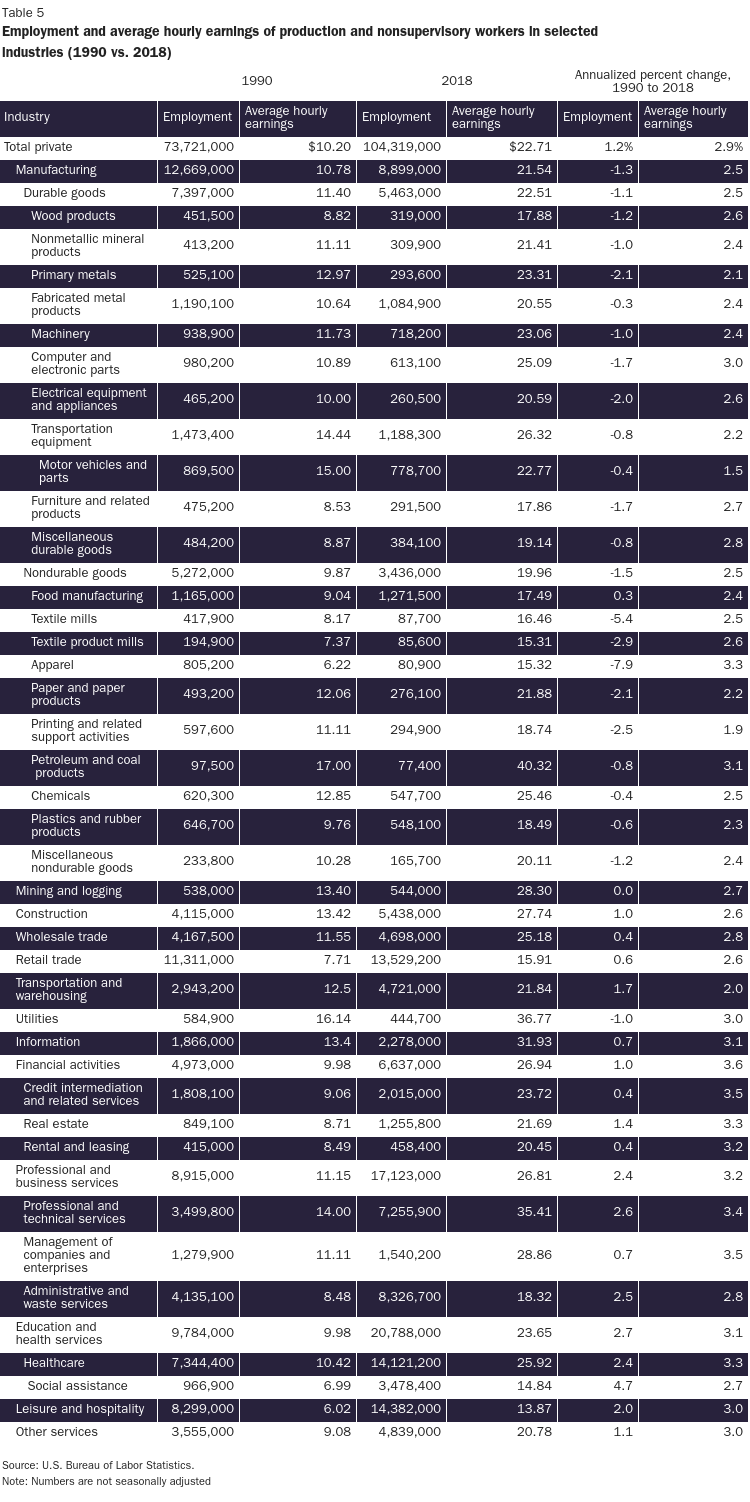

The often-heralded manufacturing “wage premium” today is small, if it exists at all. The BLS found in 2019, for example, that average hourly earnings of “production and nonsupervisory workers” in the private sector surpassed those of their counterparts in the “relatively high-paying durable goods portion of manufacturing” (non-durable manufacturing pay was even lower). By contrast, many “blue collar” services jobs in the United States not only have grown faster than manufacturing jobs since 1990 but also have higher hourly earnings and faster wage growth. Most of these services jobs are also expected, unlike manufacturing jobs, to increase in number in the future. (For more on the “new middle class jobs,” see this recent piece from AEI’s Michael Strain.)

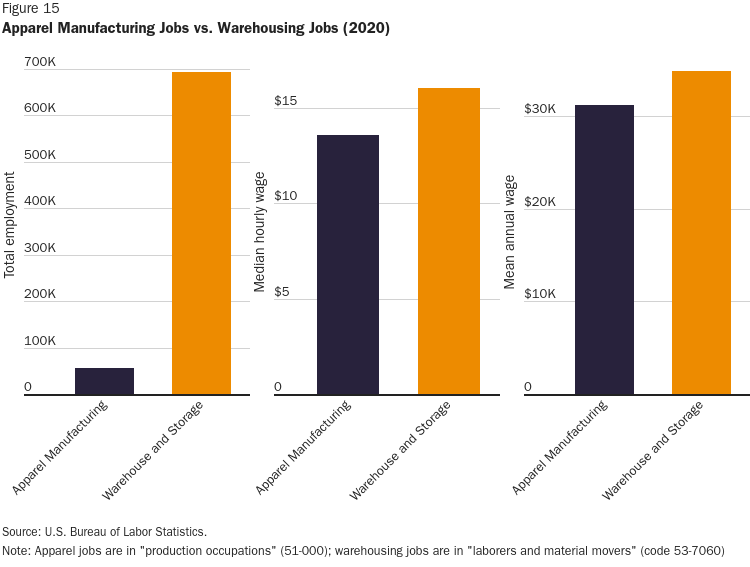

One great example of this trend is in warehousing and transport, which has exploded during the pandemic and is pulling workers away from low-skilled manufacturing work. Indeed, as I showed in a recent blog post on the Amazon union vote in Alabama, it now pays more to transport and deliver the proverbial “cheap T-shirt” than it does to make it:

Reams of anecdotal evidence back this up. Today American manufacturers routinely report—to the press or in the Federal Reserve’s quarterly Beige Book, for example—having difficulty attracting workers, even when offering higher wages and better benefits. This trend existed before the pandemic but appears to have accelerated in recent months. Getting into the weeds of what’s driving this is beyond the scope of this newsletter (some brand new research here, if you’re interested), but—regardless—it’s long past time we stopped treating manufacturing jobs as so essential for the American working class as to warrant special government support (even assuming said support would work). Surely, there are still well- paying jobs in the sector, but many of those require education and training (making them more “gray collar” than blue) and—because they’re highly productive (meaning more output and fewer workers)—limited in number.

Perhaps for these reasons, some industrial policy fans who used to base their advocacy in part on the need for lots of “good middle-class manufacturing jobs” (or whatever) have suddenly abandoned the talking point.

It’s a start, I guess.

Summing It All Up

So, it turns out, both trade skeptics and free traders may have been wrong about globalization and inequality, in ways that challenge the current conventional wisdom about why the American working class needs “America First” (Trump) or “worker-centric” (Biden) trade policies to offset a widening rich-poor gap. Trade wars aren’t class wars after all, and instead they (and trade liberalization) affect almost all of us in the same ways. That should be seen as good news in Washington—at least for those of us who want to see U.S. trade policy get back to real-world economics and geopolitics and stop being a totem in the current culture wars. For those profiting (politically or financially) from said wars, however, the trade policy class struggle will inevitably continue—regardless of what the data say.

*As we’ve discussed here repeatedly, there are several flaws in this thesis. Not only does economic nationalism impose high costs and often fail to meet its objectives, for example, polling on trade policy continues to show that Americans still don’t care or think about trade and, when asked directly about it, still tend to support it (even in the middle of a global pandemic!). But that’s a story for another time.

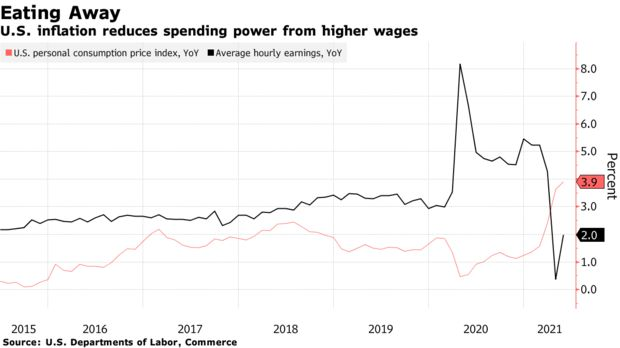

Chart of the Week

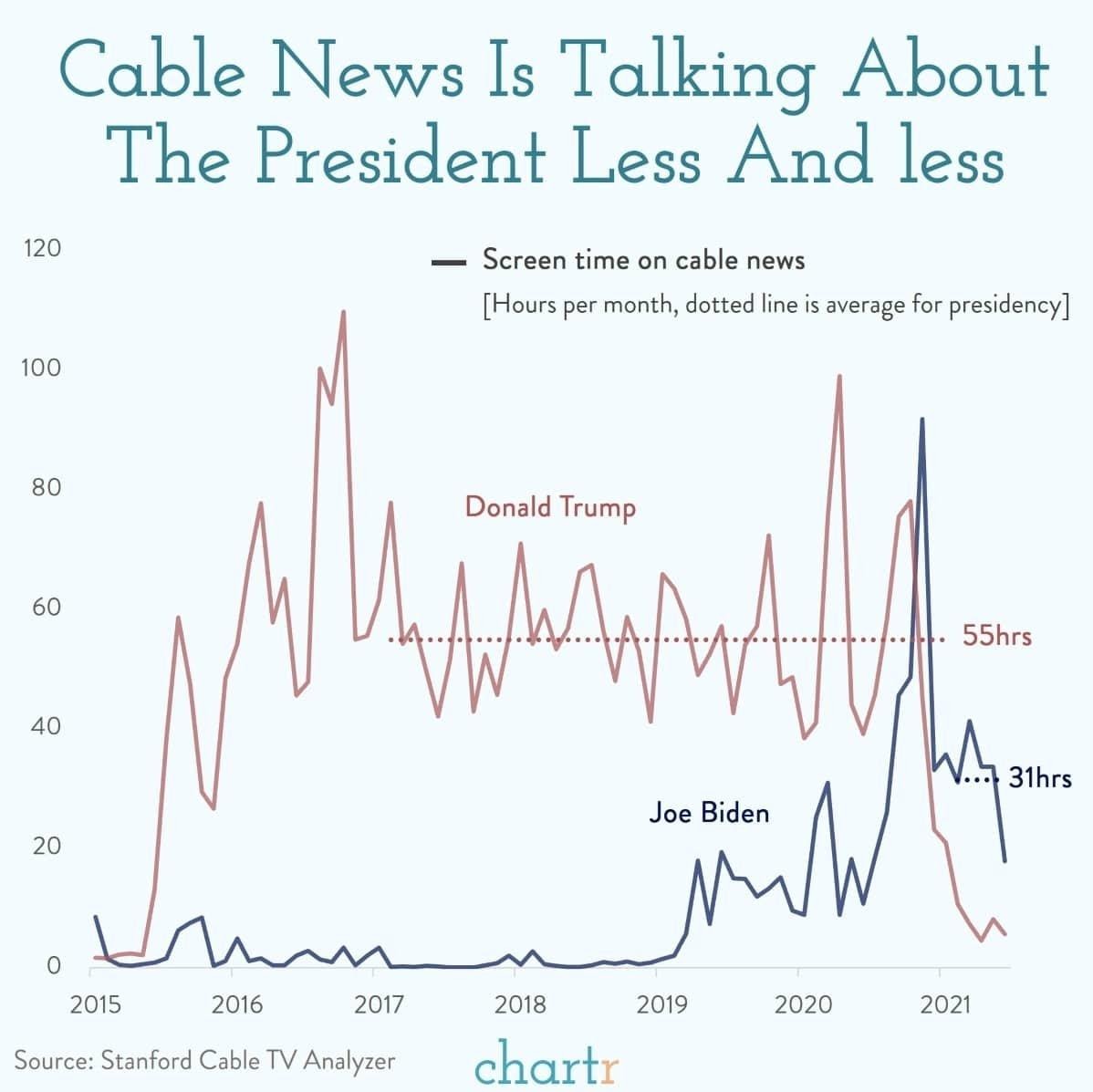

Bonus Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.