Imagine you woke up one day to discover that someone had invented a small, inexpensive contraption that could make anything you needed—food, clothes, appliances, whatever—with the push of a button. Would your life be better as a result? Would your current income go further? Would your job be easier? Would you have more free time to do the things you wanted to do, instead of the things you had to do?

For most people (including me), the answer to those questions would be yes. Many would, of course, still be concerned about all the people who worked in industries now made obsolete by the miracle machine, and they might worry about the environmental implications of suddenly disposable stuff or about the machine’s origins. But on the simple question of whether instant, free access to most of our daily necessities would make us better off, it’d be a no-brainer response for the vast majority of the American population.

Then again, maybe not?

I’ve been thinking about this hypothetical—standard in many economics classes and Star Trek conventions—a lot in recent days, as Republicans and their allies have shifted from saying President Donald Trump’s tariffs won’t raise prices to saying that, well, maybe high prices aren’t so bad because who really needs cheap stuff after all. Most prominent in this regard is Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who in early March acknowledged the potential for tariff-related price hikes but added, “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream,” which is instead “rooted in the concept that any citizen can achieve prosperity, upward mobility and economic security.” He’s certainly not alone.

I have a short piece pushing back on such assertions in The Atlantic this week, but that article leaves out a lot of detail that Capitolism readers have come to know and love (right?!). And because Bessent just doubled down on this new economic message over the weekend, I want to expand on why cheap stuff—whether imported or domestic—isn’t the “American dream” but sure as hell helps us achieve it.

‘Cheap’ Means Affordable (and Affordable Is Very Good)

The most obvious place to start is the immense benefits we all get from access to “cheap stuff” and from policies that help expand that access. As I note in The Atlantic piece, every one of us is a consumer that devotes a substantial portion of our incomes to “essential goods such as clothing, food, shelter, and energy—goods made cheaper and more plentiful by international trade.” Thanks to the internet and the rise of digital trade, moreover, we increasingly benefit from “internationally traded services too, whether it’s an online tutor in Pakistan, a personal trainer in London, a help-desk employee in India, or an accountant in the Philippines.” And, as anyone who’s ridden in an American car from the early 1980s understands, we benefit from this access even when we buy American, because domestic goods and services become better and cheaper when they’re forced to compete with imports on quality or price.

Protectionists routinely denigrate these benefits as merely saving a few cents off a cheap T-shirt or toaster, but as I noted in the piece, those pennies add up: “Overall, studies conservatively estimate that American households save thousands of dollars a year from the lower prices, increased variety, and global competition fomented by international trade.” Even the much-denigrated China Shock provides such gains, as I summarized in a recent essay: “For each percentage point increase in Chinese imports, consumer prices fell by nearly 2 percentage points, with savings from both imports and domestically produced goods (thanks to heightened competition).” That translates (well, it translated) into hundreds of dollars a year in annual savings for each U.S. household—gains disproportionately accruing to middle- and low-income Americans because “the most affected products were those often sold at big-box retailers, such as Target and Walmart.”

Given how much Americans today care about the cost of living (and how it dominated the 2024 election), it’s certainly not a coincidence that Trump officials and other protectionists routinely describe the affordable imports they wish to tax as “cheap.” For many people, the adjective implies not merely low prices but also low quality. Yet this ploy ignores not only the word’s primary dictionary definition (low price, good value, etc.), but several inconvenient realities. Most obviously, the administration’s tariffs apply to goods from not just to China but also Canada, Mexico, and—in the case of steel and aluminum goods and forthcoming “reciprocal” tariffs—many other countries in the world. The tariffs also aren’t in any way distinguishing between high- and low-quality goods—they’re just a blanket tax on stuff Americans want, often because they’re “cheaper.”

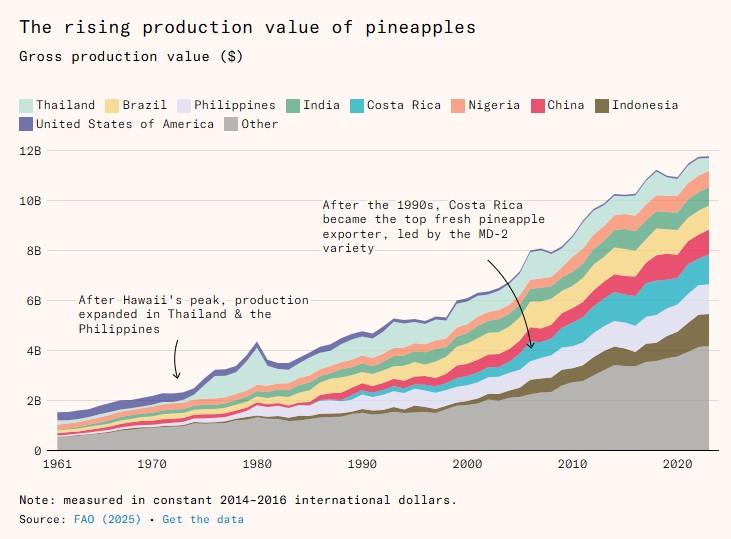

The denigration of “cheap” things also ignores their clear role in improved human well-being. As detailed in this excellent new essay on how pineapples became commonplace, things we consider cheap and mundane today were often once luxury items—and it’s the very process of “cheapening” something, via generations of international trade and technological innovation, that raises our living standards over the long term (emphasis mine):

Most luxury goods have intrinsic desirable qualities, like the pineapple’s sweet taste. But often, they are luxuries primarily because they are positional goods: their value comes from showing off status. When procuring a pineapple is difficult or costly, displaying one is a strong, unfakeable ‘signal’ of wealth. This, however, increases demand, which gives entrepreneurs like Keeling and Hunt or James Dole an incentive to provide pineapples at a lower price. For a time, the poorer people who can now afford them may benefit from the lingering prestige, but eventually, society catches on, and the prestige vanishes.

Thus luxury is self-defeating: any particular luxury good, unless inherently limited in supply (like historical artifacts or real estate near Central Park), can eventually become mundane. Aluminum used to be more precious than gold and is now common enough to be used in disposable packaging. Purple dye used to be reserved for Roman emperors; now we have cheap ways of manufacturing pigments in any color. Spices, mirrors, ice, citrus fruit, and even celery are all examples of items that used to attract the attention of the wealthiest but have now become widely available at very little cost. All of them are victories for our quality of life.

As noted in the essay, pineapples also show that things can be both inexpensive and high quality, and that, in a free market, entrepreneurs and traders will continue to improve their products—better taste, more variation, longer-lasting, etc.—even after they’ve gotten “cheap.”

Cars, consumer electronics, and many other goods show similar dynamics, but even lower quality “cheap” stuff has value when the alternative is having nothing at all. It’s easy for someone like Bessent, who’s worth about $500 million, to denigrate “cheap stuff” because he can afford the best clothes, shoes, appliances, cars, consumer electronics, and so on. Most Americans, however, can’t—and “cheap” versions of these things give us access to a decent facsimile of what the richest Americans have but at a fraction of the price.

Cheap Stuff Means Higher Incomes and More (and More Enjoyable) Free Time

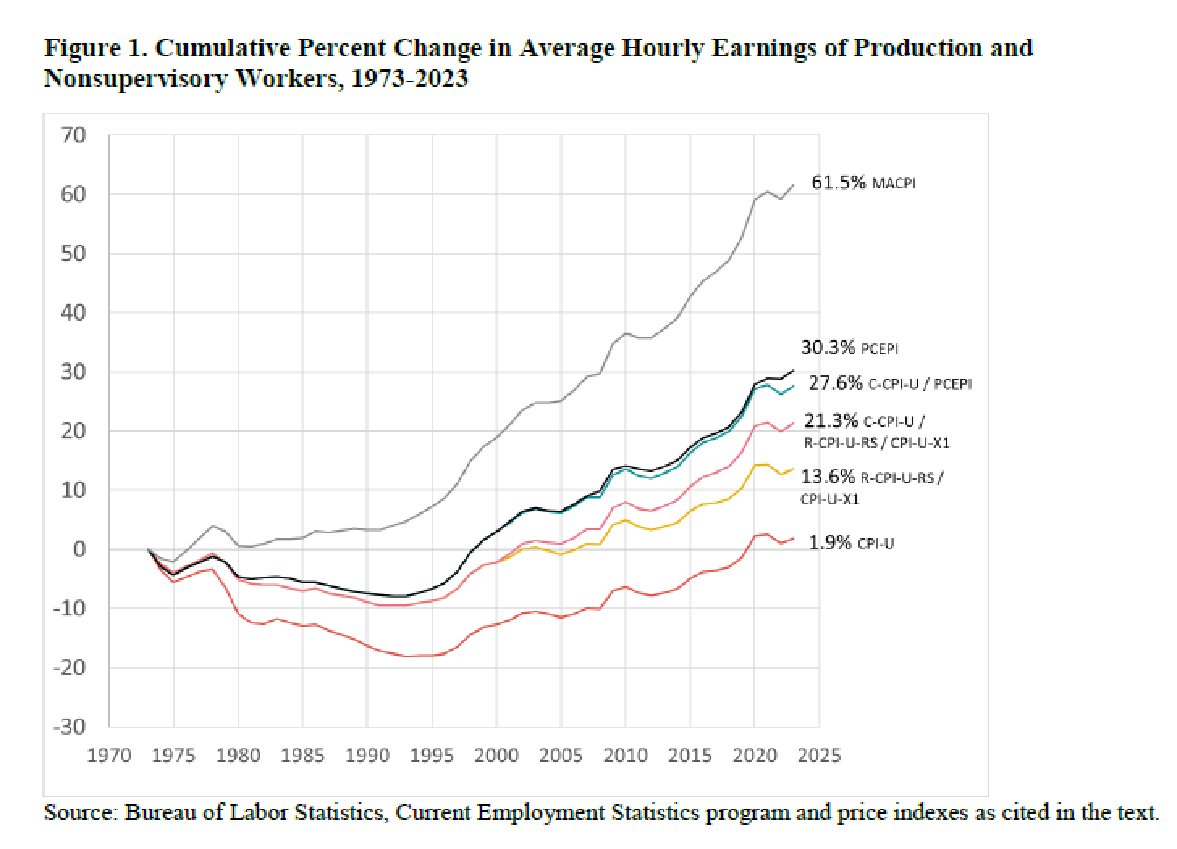

Just as importantly, having such access isn’t merely about the “stuff” itself but how it translates into higher incomes over time. As I noted in The Atlantic, we just spent a couple years—and an entire election season—relearning how “bigger numbers on your paycheck mean nothing if you’re forced to spend even more on the things you need and want.” And, as we’ve discussed here repeatedly, the biggest reason why claims of persistent American “wage stagnation” are wrong is because they depend on figures that substantially overstate how much stuff costs. Lower and more accurate measures of inflation, by contrast, show that middle-class workers have seen much higher real income gains over the last several decades. As shown in the following chart from Scott Winship of the American Enterprise Institute, real blue-collar earnings since the 1970s go from depressingly flat to impressively good depending on how we measure the actual cost of goods and services that Americans consume over time (i.e., inflation):

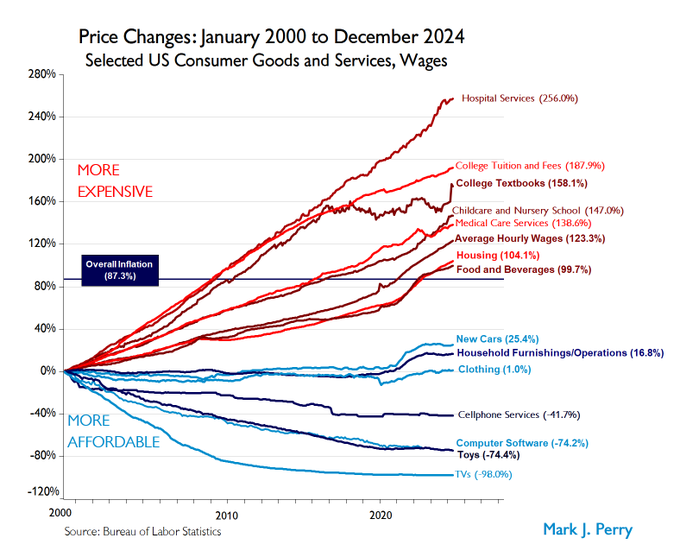

Trade certainly isn’t the only thing driving those positive trends, but as I note in my piece, “One of the big reasons Americans’ inflation-adjusted wages have climbed in recent decades is that the exorbitant prices of things such as housing, health care, and education have been offset by significant declines for tradable goods such as toys, clothing, and consumer electronics.” Here’s a telling chart from economist Mark Perry:

Raise the price of this stuff (and of stuff like home construction materials), and you lower Americans’ real incomes—especially for those at the bottom of the wage scale. As documented in my 2023 book, the poorest 20 percent of U.S. households devote almost 70 percent of their annual incomes to shelter, food, transport, utilities, and clothes—things often affected greatly by international trade and often subject to tariffs. The wealthiest 20 percent of households, by contrast, spent just a little more than 50 percent of their incomes on the same things. Throw in the fact that large, young households consume more than smaller, older ones, and you can hopefully see why a policy that intentionally makes “cheap stuff” less cheap will reduce the income and living standard of a single mom with four young kids far more than, say, that of a 62-year-old treasury secretary worth a few hundred million dollars.

Trade is also important for Americans’ leisure and economic mobility. For starters, disposable income—money we have left over after buying “cheap” necessities—can be invested in things such as education and retirement or can be saved for a rainy day or for a big important purchase like a house or a fun family vacation. A trip to Mexico, in fact, is an imported travel service, while the planes we take, the clothes we pack, and the suitcases in which we pack them contain imported parts or come from abroad. Local leisure activities—video games and streaming services at home, sports and outdoor recreation nearby, etc.—also depend on “cheap” imports (and often foreign creators).

Just as importantly, trading for necessities instead of making them ourselves means that Americans have more time to enjoy these things or to do more productive things like learning a new skill or training for a new career. As I noted in The Atlantic, in fact, a new study in the Journal of International Economics, found that “between 1950 and 2014, trade openness contributed to an additional 20 to 95 hours of leisure per worker per year,” owed to the higher real incomes trade produced. In the authors’ no-trade alternative, meanwhile, we’d have to work 20 more days per year to compensate for the annual income we’d lose due to a complete shutdown of trade.

Yikes.

These principles and findings aren’t just economic mumbo-jumbo. They’re also commonsense and something we each do every day. Instead of buying “cheap” stuff at the store, we could grow our own vegetables or make our own clothes (or raise our own chickens). But the time and money we’d devote to those efforts—not for fun but for survival—is time and money we couldn’t devote to our current jobs, our families, our hobbies, our communities—or to planning a move up the economic ladder or to another town with better opportunities or better quality of life.

Millions of American Jobs Depend on Cheap Stuff

Finally, let’s discuss the false choice Republicans are offering between cheap stuff and American jobs. We’ve been over the relationship between trade and modern U.S. manufacturing repeatedly, so for that I’ll just quote myself:

The counterargument—until recently associated with the political left—is that cheap and varied consumer goods are not worth sacrificing the strength of America’s domestic-manufacturing sector. Even if we accept that (questionable) premise, however, it doesn’t justify Trump’s tariffs, because those tariffs will hurt domestic manufacturing too. About half of U.S. imports are intermediate goods, raw materials, and capital equipment that American manufacturers use to make their products and sell them here and abroad. Contrary to conventional wisdom, these imports increase domestic-manufacturing output and jobs. Thus, for example, an expanding U.S. trade deficit in automotive goods has long coincided with gains in domestic automotive output and production capacity, and past U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum caused a slowdown in U.S. manufacturing output. Even if domestic manufacturers don’t buy imported parts, simply having access to them serves as an important competitive check on the prices of made-in-America manufacturing inputs. This is why Trump’s recent steel-tariff announcement gave U.S. steelmakers a “green light to lift prices,” as The Wall Street Journal put it.

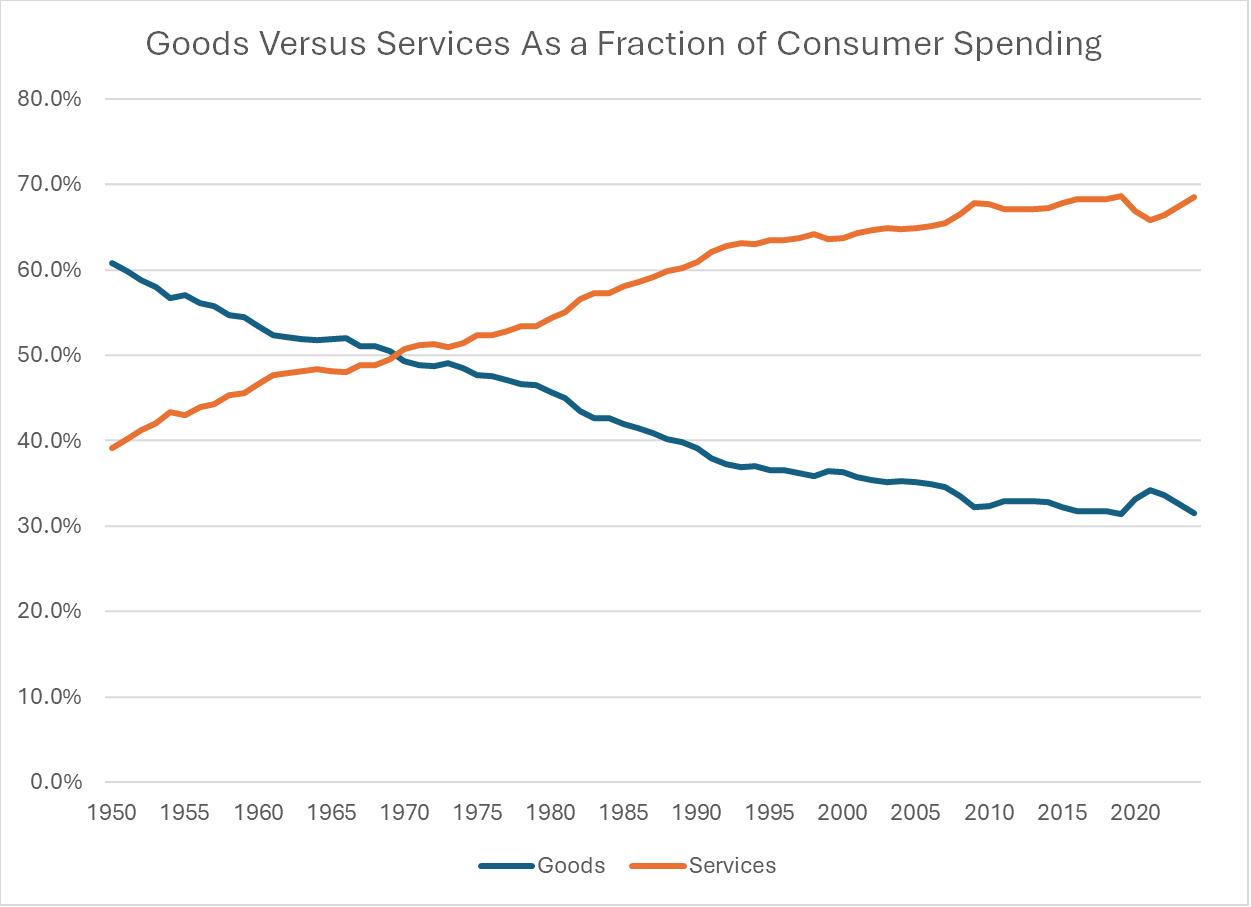

The benefits of cheap stuff also extend to American services industries and workers (which of course represent a much greater share of the U.S. economy than does manufacturing). Goods made offshore and then imported by “factoryless manufacturers” in the United States—firms like Amazon, Nvidia, or Nike—let these companies expand their onshore work in research, design, marketing, and other services. Imported lumber, nails, steel rebar, and other materials boost American homebuilders and construction workers. Imported laptops, servers, and smartphones help Americans working in U.S. professional, financial, educational, or high-tech services. Imported drugs and medical goods help hospitals, doctors, and nurses (and patients too), and imported food helps grocers and restaurateurs. Even just transporting and selling “cheap stuff” supports millions of other American services jobs in warehousing, transportation, logistics, and retail. The list goes on and on.

It’s these kinds of forces that help to explain why the “China Shock,” which is usually discussed in terms of only manufacturing job losses, has also been found to have boosted American services. Here’s one example from my longer paper on the subject:

Researchers with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco have estimated that about 56 cents of every dollar that Americans spent on “Made in China” imports in 2018 actually went to American firms and workers—the highest share of any country. Such benefits make sense: 2019 U.S. labor market data show millions more “blue collar” American jobs that might benefit from Chinese imports—in transportation, logistics, construction, and maintenance and repair, for example—than in manufacturing.

As I go on to note in the paper, many U.S. manufacturers have benefited from Chinese imports, too. Whether some of those imports nevertheless represent a real national security issue is a separate issue worth exploring, of course, but we shouldn’t pretend that this cheap stuff—and especially similar goods and services from almost everywhere else in the world—doesn’t have real value for millions of American workers in all sorts of fields.

Even when it’s cheap.

Summing It All Up

In reality, the Republicans’ new message isn’t really all that new at all. In 2022, for example, Robert Lighthizer, the former Trump administration trade representative, told a conservative conference that, “The best way to fix consumerism is to raise prices,” and derisively asked—as inflation was in full swing, no less—whether consumption was “really a problem in America” today. A few months later, Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts took to the pages of the American Conservative to sneer at “cheap credit, cheap imports, or cheap foreign labor.” Other self-styled conservatives were saying similar things around the same time.

As I concluded in The Atlantic, however, this old message hasn’t historically come from conservatives. It’s come from the progressive left:

Democrats used to be the ones offering a false choice between Americans’ access to affordable (often imported) stuff and our economic well-being. In 2007, then-Senator Barack Obama told a union-sponsored-debate audience in Chicago that “people don’t want a cheaper T-shirt if they’re losing a job in the process.” And Bernie Sanders famously said in 2015 that Americans “don’t necessarily need a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers when children are hungry in this country.”

No surprise, then, that in championing Trump’s protectionism today, at least one prominent advocate has openly and proudly described it as a “leftist agenda.”

Points for honesty, I guess.

Anyway, back in the old days, Republicans cheered—as George W. Bush did just a few weeks after Obama’s statement—the “more choices and better prices” that Americans enjoyed from trade. They praised—as Republican Ways and Means Committee members did just days before Sanders lamented our deodorant abundance—Ronald Reagan’s direct linkage between “American trade” and “the American dream.” Today, only a few Republican outcasts, such as Mike Pence in responding to Bessent’s comments, say similar things—even as the ones in power quietly embrace foreign imports to help temper high U.S. egg prices.

Sadly, it seems, “cheap goods” and the laws of economics only still matter for some on the right when it’s a politician’s American Dream on the line.

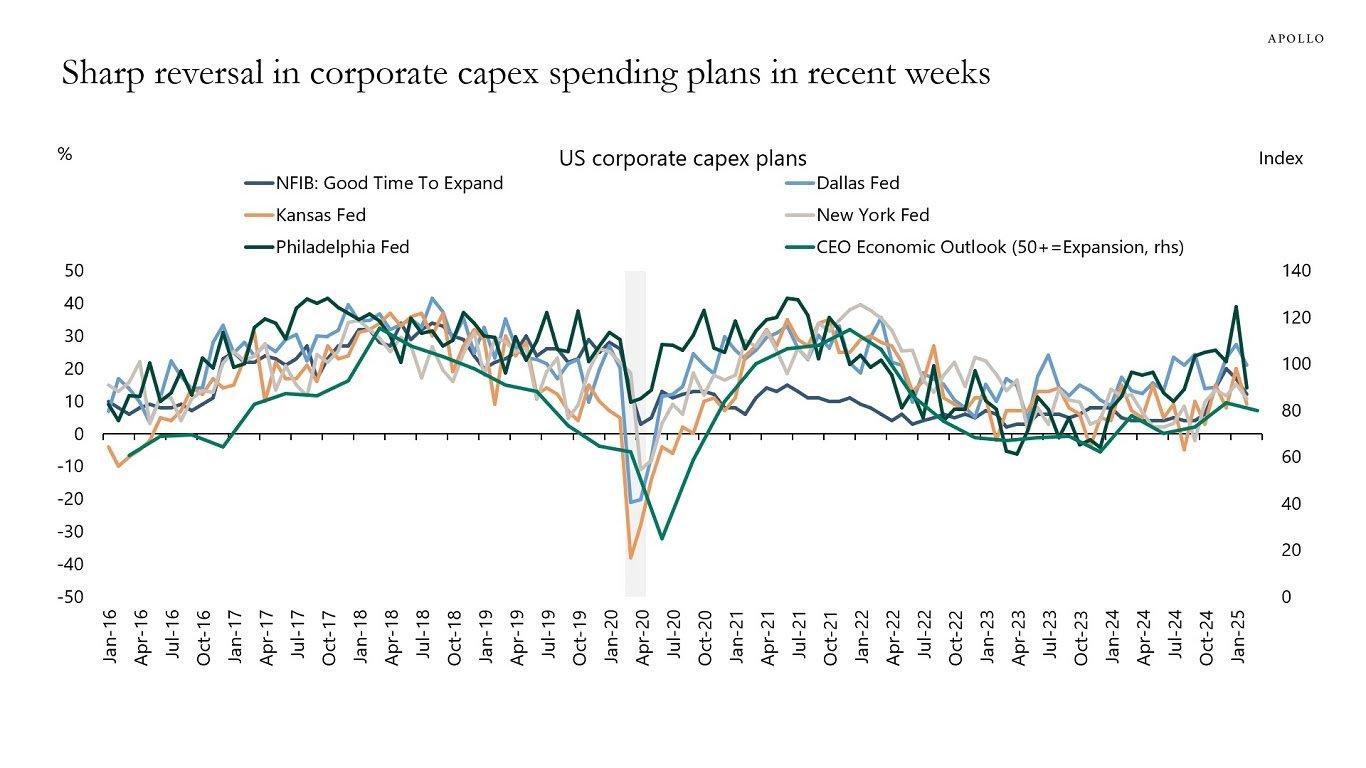

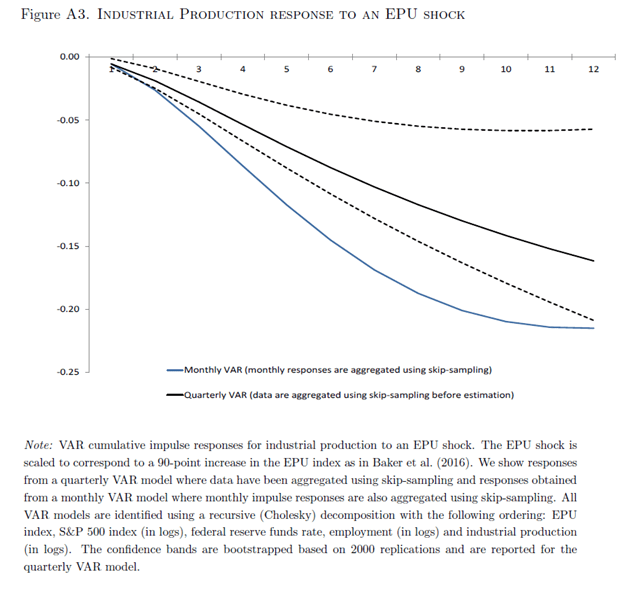

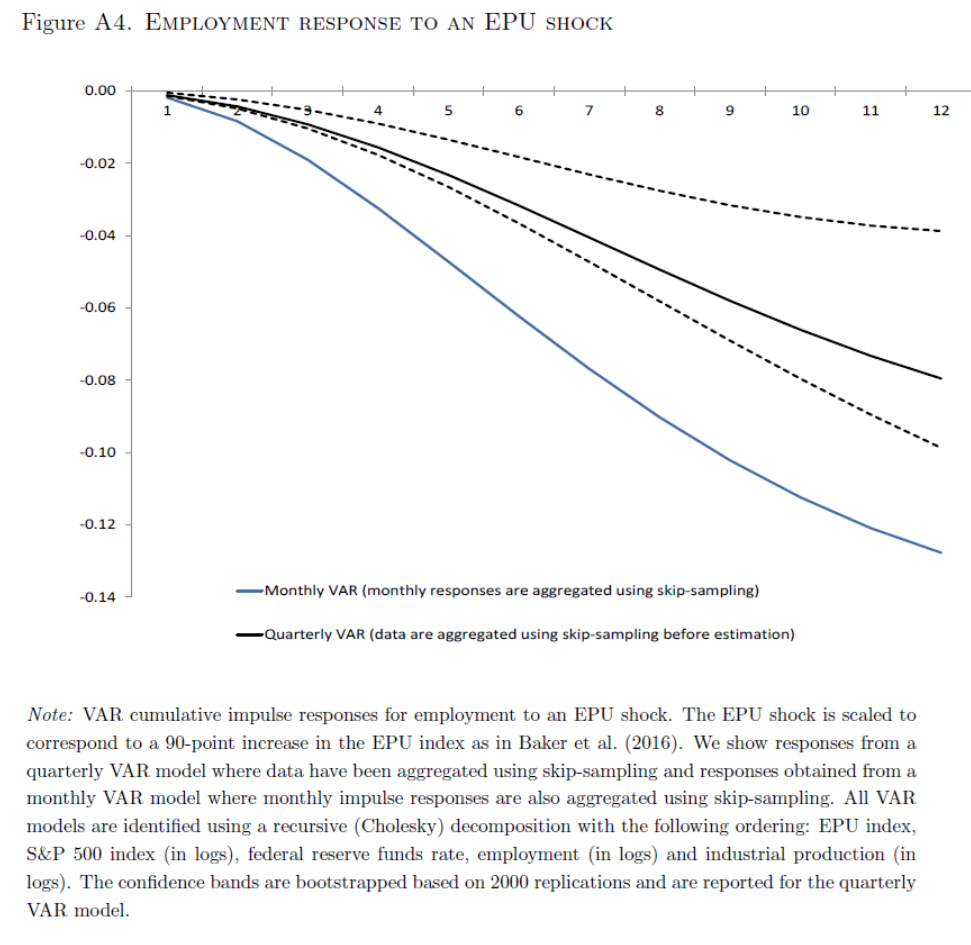

Charts of the Week

The Links

New from me on Canada/Mexico tariffs and potential lumber tariffs

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.