Dear Capitolisters,

As you’ve probably read (at least a dozen times), last week was the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That naturally produced numerous stories on Ukraine’s surprising resiliency in the face of presumably overwhelming Russian aggression, as well as a ton of U.S. ink spilled about Washington’s support for the Ukrainian resistance. Today, however, I want to look a lesser-covered part of the yearlong war: Europe’s rapid independence from Russian energy and some of the lessons it should teach us about trade and markets.

In short, things can and do change—and they do so very, very quickly when people are both highly motivated and relatively free to act on that motivation.

The 2022 European Energy Crisis (That Kinda Wasn’t)

As you’ll recall, the early days of the war featured a lot of wailing and gnashing about how dependence on Russian energy would prevent Europe—especially Germany—from vigorously opposing the invasion and backing any Ukrainian opposition. This situation, in turn, generated a lot of laments about how Russia’s invasion was a stark reminder of how the United States mustn’t be “dependent” on foreigners for any essential goods. But pessimism—about Europe, at least—wasn’t limited to hawkish, nationalist hot-takers. A February 2022 Wall Street Journal news story (not opinion), for example, explained that a significant reduction of Russian gas supplies would be disastrous for Europe because the other top suppliers were “essentially tapped out” and, even if they weren’t, Europe lacked the infrastructure to boost imports of liquified natural gas (LNG). Even I, ever the optimist, shared that article in my initial thoughts on the Ukraine mess back in March of last year.

But a funny thing happened on the way to European energy market collapse—it never really happened, even as the Journal’s worst case scenario unfolded and Russia ceased most natural gas exports to Europe in fall 2022 (“gas flows from Russia to Germany… shriveled from 55% of imports last year to zero”). Energy prices spiked, economic output dropped, and things got otherwise dicey (technical term) last year, but Europe didn’t fall apart and now appears to be on the upswing. So what happened?

In short, mere days after the Russian invasion began both private and government actors started adjusting.

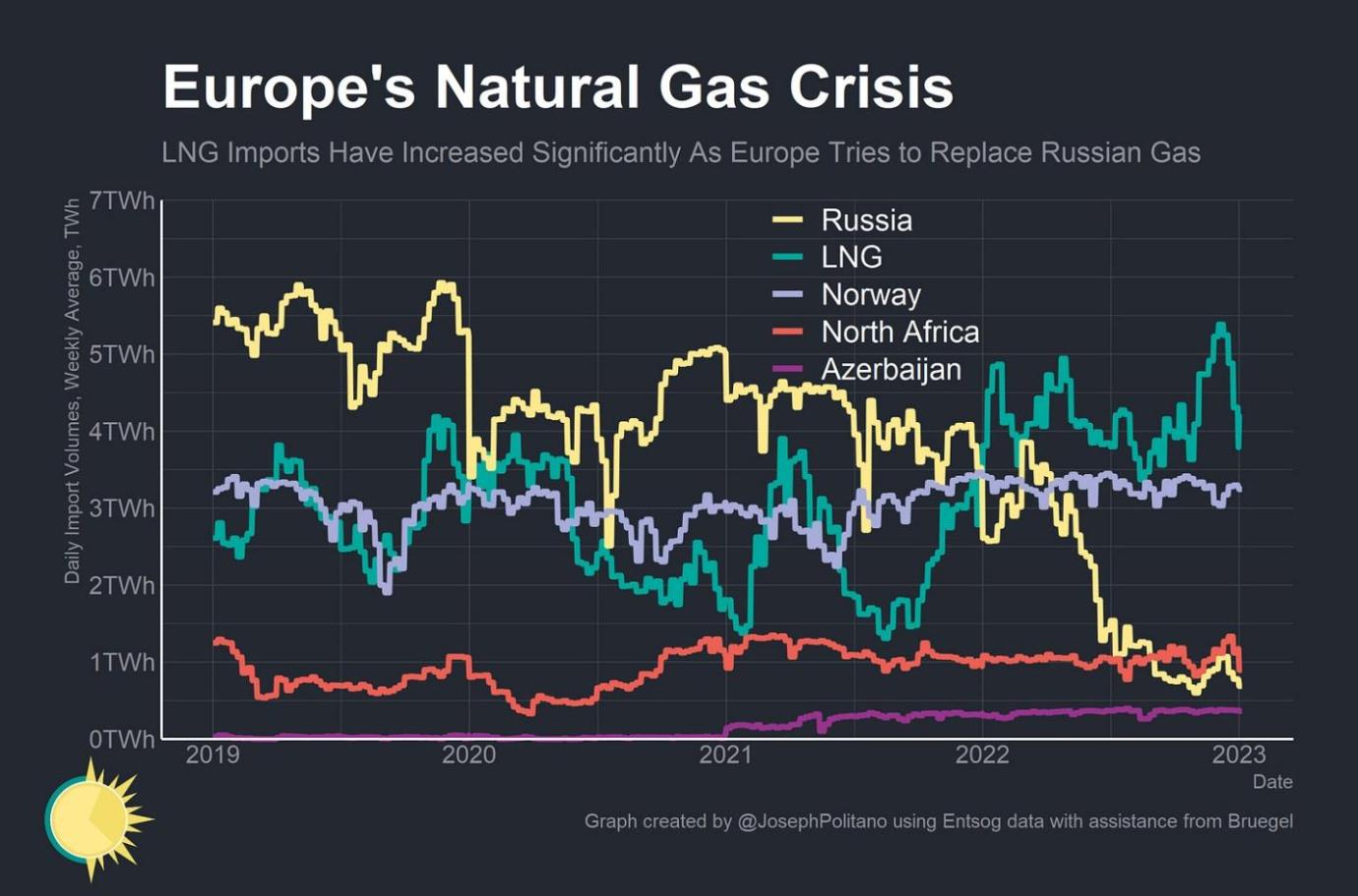

Most notably, Europe rapidly diversified its traditional energy supplies away from Russia. As I briefly noted in a previous newsletter, economist Joey Politano last month provided a great series of charts documenting the continent’s transition away from Russian pipeline gas and toward LNG imports. In fact, “[t]he rise in LNG imports means that the EU still imports essentially as much natural gas as it did before the invasion of Ukraine—it’s just that much, much less of it comes from Russia.”

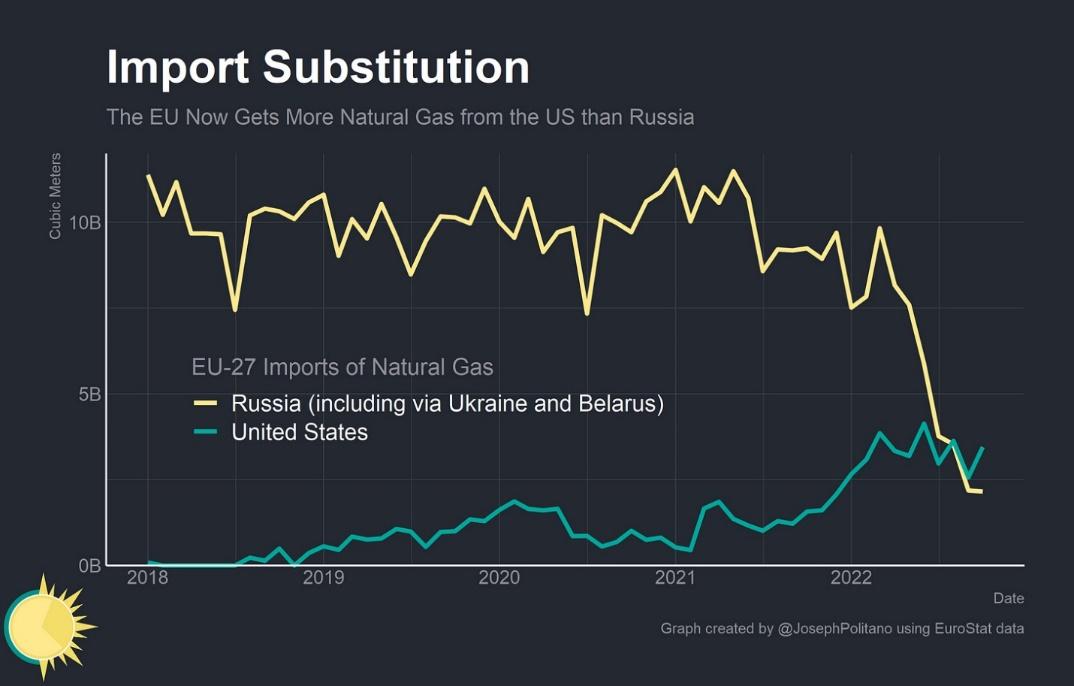

Supplying much of that LNG were producers in the United States, which actually surpassed Russia as a European gas supplier late last year:

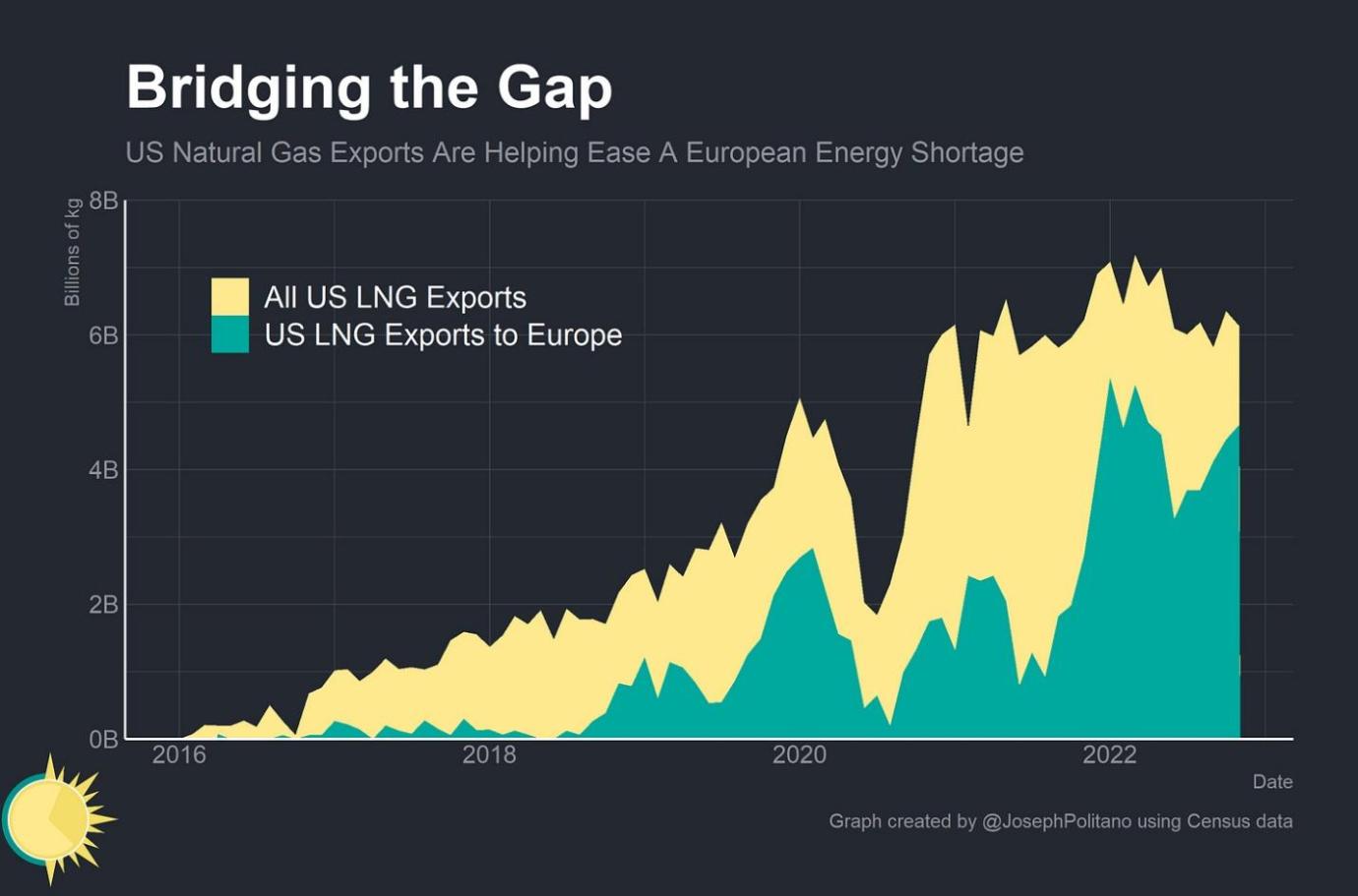

This supply surge was possible because companies rapidly diverted U.S. LNG supplies to Europe from their previously destinations in Asia:

But how did this shift happen so quickly? Two words: corporate greed.

More seriously, it turns out that relatively higher prices in Europe did exactly what higher prices do: attract profit-seeking suppliers and encourage them and others to invest in future supply too. And, as Politico explained last week, the initial push was enabled by flexibilities built in to private U.S. LNG contracts:

Frank Fannon, a former State Department first assistant secretary for energy resources under the Trump administration, said the decision by U.S. companies to structure their multi-year delivery contracts to allow buyers to ship the gas wherever they wanted played a major role in overcoming Russia’s switching off its pipelines. That market innovation allowed European buyers to persuade the Asian companies that held the gas contracts to reroute them toward the EU— for a price.

“I would find it unimaginable there would be a chance of weathering the storm in Europe but for American LNG,” said Fannon, who is now managing director of energy and geopolitical advisory firm Fannon Global Advisors. “It’s absolutely inconceivable. It isn’t just the volumes of U.S. gas, but also the way that American companies have transformed the market.”…

“U.S. LNG is going to Europe because they’re paying a higher price,” [Columbia’s Ira] Joseph said. “It’s not a natural gas Marshall Plan here. There’s no American Inc. exporting LNG.”

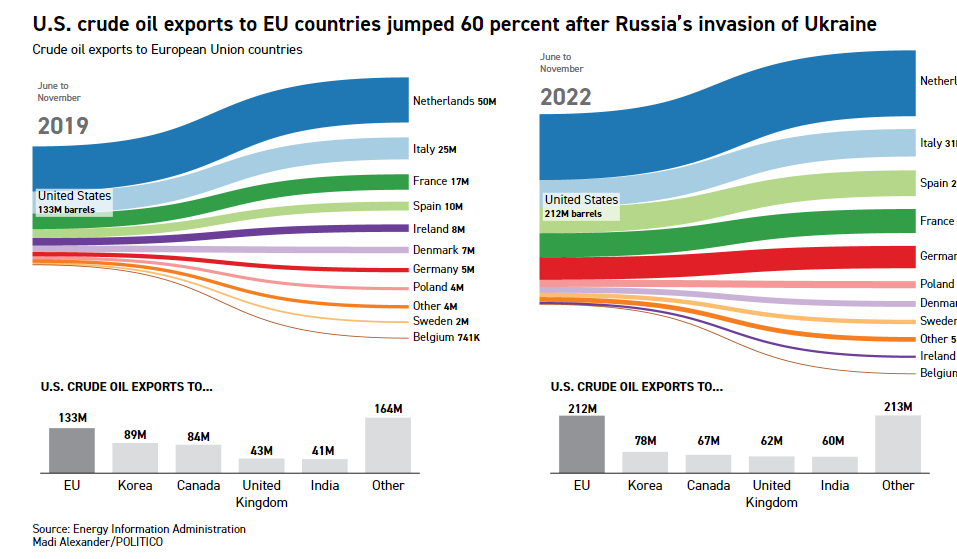

Profit-hungry American oil exporters did much the same last year:

As Politano notes, this incredible support for the European economy happened even as the Freeport LNG terminal in Texas, which accounts for around 20 percent of total U.S. LNG export capacity, went offline last June and remained down for months longer than expected. It began loading cargo again earlier this month and will be running full-tilt in April. The U.S. Energy Information Administration further forecasts that 2023 will see record LNG export volumes (up about 15 percent over 2022), with even more export capacity coming online in 2024.

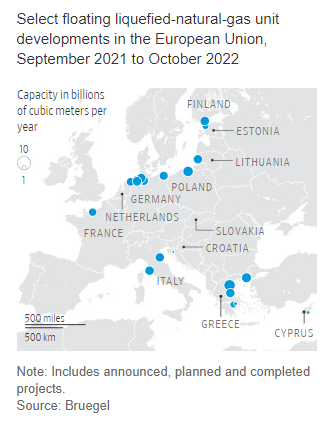

Meanwhile, European nations finally got serious—really serious—about building the infrastructure needed to import even more LNG volumes. Thus, as the Journal documented late last year, “[d]ozens of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, facilities are slated for construction across the European Union in coming years, which would allow Europe to buy more gas from nations such as Qatar and the U.S.”

As the map above shows, Germany has been leading this charge and is now home to 13 different LNG projects—10 floating terminals and three onshore facilities (though some of the former will be taken offline when the latter are built). In fact, two floating terminals are already operational—a breathtaking achievement for projects that, even in the best of times, usually take years, not months, to complete. As the Journal explains, this resulted from an all-of-government approach to the Russian gas problem—one that, importantly, centered on substantial regulatory and permitting reform:

The German bureaucracy made adjustments, too. The parliament passed an LNG Acceleration Act, speeding up procedures for reviewing, approving and awarding contracts for LNG projects.

“If there is a chance in this really terrible situation, it is that we shake off all this sleepiness and, in some cases, grouchiness that exists in Germany,” Economy Minister Robert Habeck said in March about speeding up the construction of LNG terminals.

Other large construction projects have moved slowly in Germany. In 2020, Berlin opened its new airport nine years behind schedule. Stuttgart’s new railway station, under construction since 2010, is now scheduled to open in 2025, after years of delays and ballooning costs.

Thanks to these reforms, Argus estimates that “Germany is set to be the fourth-largest LNG import capacity in the world by the end of this decade, behind South Korea, China and Japan.”

This shift was not, of course, purely a private, market-driven phenomenon. Governments reacted too, including by front-loading (pre-sanctions) purchases from Russia and deploying their own strategic oil reserves:

The US and its allies, under the umbrella of the International Energy Agency, released about 314 million barrels from strategic petroleum reserves. Put simply, for each Russian barrel lost from the market in 2022, key IEA members added almost 2.6 barrels from emergency stockpiles. The bulk came from America— roughly 222 million barrels over the year. The rest, in two tranches, flowed from Germany, Japan, France, Spain, the UK and a few others.

They also deployed subsidies and imposed a price cap (“barring Western insurers, financiers and shippers that underpin much of the world’s oil trade from handling seaborne Russian crude—unless it is sold below $60 a barrel”), to keep oil flowing from Russia but deny Moscow its full value. And Europe also got lucky, as an abnormally warm winter made it easier to boost reserves.

Disaster Averted?

Surely, Europe didn’t avoid economic pain entirely—those high prices hurt consumers, fueled inflation, and curtailed domestic output and investment—and future supply crunches remain possible. But Europe’s actions seem to have foreclosed the deep recession that was, up until a few months ago, expected if/when Russia turned off the gas: “Now, the signs are that any recession will be modest, and some economists now think output will grow in this quarter. Investors have taken note, with European stocks outperforming their U.S. counterparts.”

The key to that optimism is, unsurprisingly, “falling energy prices,” which not only mean an improved energy storage and supply outlook, but also less strain on government resources from energy-related economic support (which lower prices have reduced by billions of dollars). And that rosier outlook comes from confidence in future, non-Russian energy supplies. Indeed, Germany’s Vice Chancellor Robert Hallbeck in January crowed that Russia has wasted its “leverage” over Europe because nations have successfully moved to diversify their energy supplies away from Russia and toward LNG and renewables. Fears of blackouts are now, he believes, a thing of the past.

Summing It All Up

So “greedy” oil and gas companies and motivated German deregulators joined forces to ensure that Europe’s “dependence” on Russian gas didn’t cause a massive recession (or worse). This raises at least two important policy lessons. First and most obviously, private and government actors don’t just sit back and say “oh shucks” when wars, natural disasters, or other unexpected calamities occur. They respond to events—geopolitical shifts, market changes (e.g. high prices), etc.—and adjust previous behavior to account for the new landscape and political/economic incentives. “Dependence” today isn’t necessarily “dependence” tomorrow, and years of relatively unencumbered economic growth—perhaps even supported by a previous trade or economic relationship—can generate the resources (money, industrial capacity, supply/distribution networks, etc.) needed to support an emergency response. Adopting a costly wartime stance during decidedly not-wartime can do just the opposite.

Second, the European energy situation shows some things that governments can do to mitigate potential supply shocks. Stockpiles (“strategic reserves”), for example, seem like a relatively wise and low-cost move (especially compared to dumb, costly stuff like autarky), though certainly politics can and do interfere with their optimal deployment. Just as importantly, government policy must let markets adjust—flexibility that, ideally, is in place before disaster strikes. Imagine, for example, if certain folks had gotten their way a decade ago and the federal government had not, contra my own advice at the time, liberalized U.S. restrictions on LNG export licenses and crude oil exports. (Believe it or not, many politicians and interest groups wanted to do the exact opposite—further regulating contracts, facilities, destinations, etc., and even suggesting that we ban exports entirely for environmental or industrial policy reasons—and some still do.) Not only would the U.S. industry be smaller and poorer, but it might also be more difficult for the U.S. energy exports we did have to quickly ride to Europe’s rescue.

Germany’s rapid moves on permitting reform and LNG terminal construction show that even the most entrenched policymakers can embrace change on the fly when there are strong enough political or economic incentives to do so. But it’s just as clear that regulatory reforms like the LNG Acceleration Act would’ve been even smarter if they’d been adopted years earlier (and not merely limited to LNG). Will the U.S. learn that lesson before our next supply crisis hits? As I’ll explain next week, things aren’t looking too good.

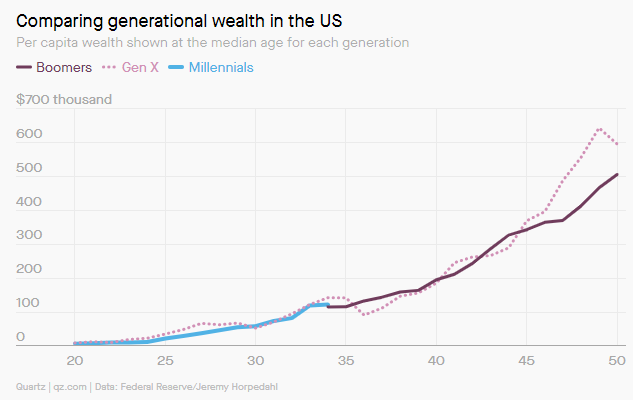

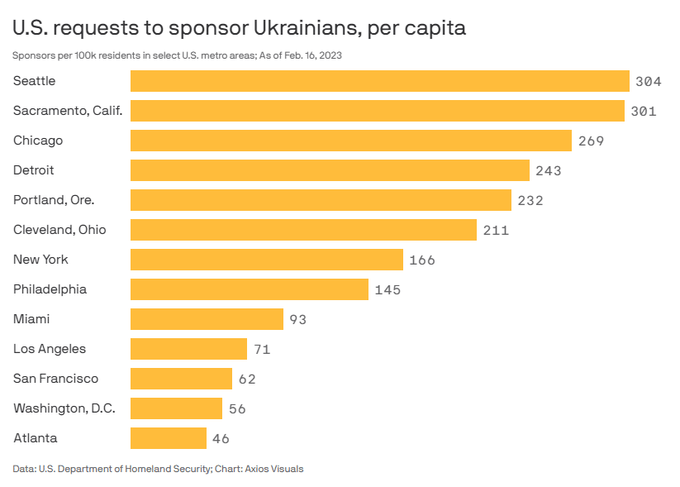

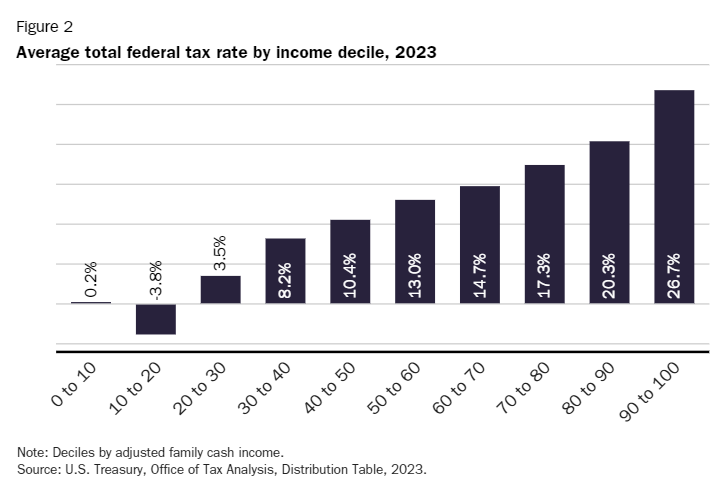

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Some recent blog posts from me on baby formula, criminal justice reform, and remote work.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.