Dear Capitolizers,

This time a year ago, the stock market had begun its epic collapse, and our new COVID-19 reality was just about to set in. It’s been a rough go ever since, with the lucky ones suffering only disappointment—closed schools, ruined holidays, canceled vacations, rough toilet paper—instead of tragedy. The repeated implosion of our hopes and plans has, I think, caused many of us to embrace an eternal pessimism about the pandemic and our eventual return to normalcy—one seemingly shared by a lot of journalists, public health experts, and political leaders who rarely miss an opportunity to follow up good news with the possible downsides, no matter how remote.

This pessimism is not only annoying to us eternal optimists (I’m also a morning person, so hate away, haters), but—as laid out in a recent piece (and accompanying Twitter thread) by the New York Times’ David Leonhardt—also damaging for the country’s fight against COVID-19 and the economic recovery that hinges on it. In short, there’s a large and ever-increasing pile of evidence that the vaccines work incredibly well and the worst of the virus is behind us, but incessant alarmism and nitpicking—it’s not 100 percent; it doesn’t prevent transmission; what about the variants; the science isn’t ironclad; we’ll be masked till 2022; etc.—is undermining the very public support that’s needed to make the vaccines a true success (and thus let us get back to our lives). The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson provided a timely and frustrating example on Monday:

Such pessimism might—might—have been warranted in December when few people had taken the vaccines, COVID-19 cases were skyrocketing at home and abroad, and the economy was still in bubble wrap, but the facts on the ground have changed since then. A lot. And while surely some hurdles and unanswered questions remain, today there are plenty of reasons for optimism about our near future—optimism that should, for our mental, physical, and economic health, be more widely reported. In short, spring is coming—literally and metaphorically—and today we’re going to spend some time being happy about it.

The Vaccines

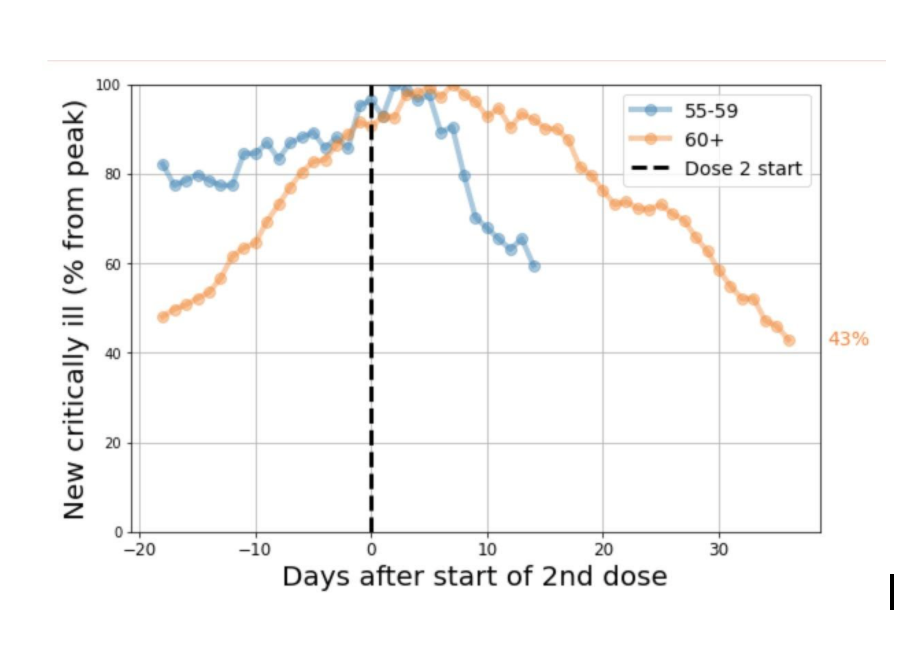

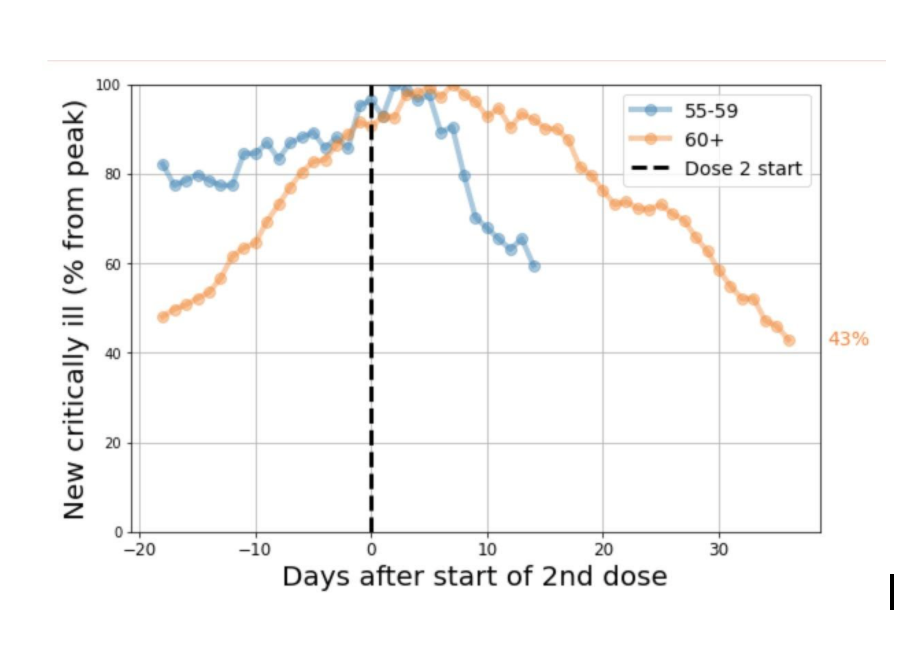

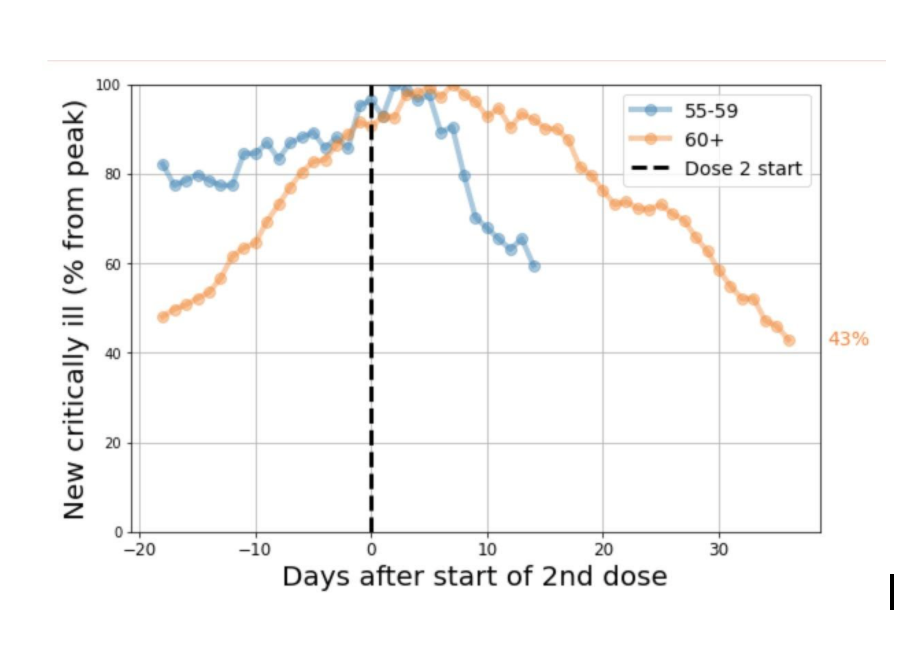

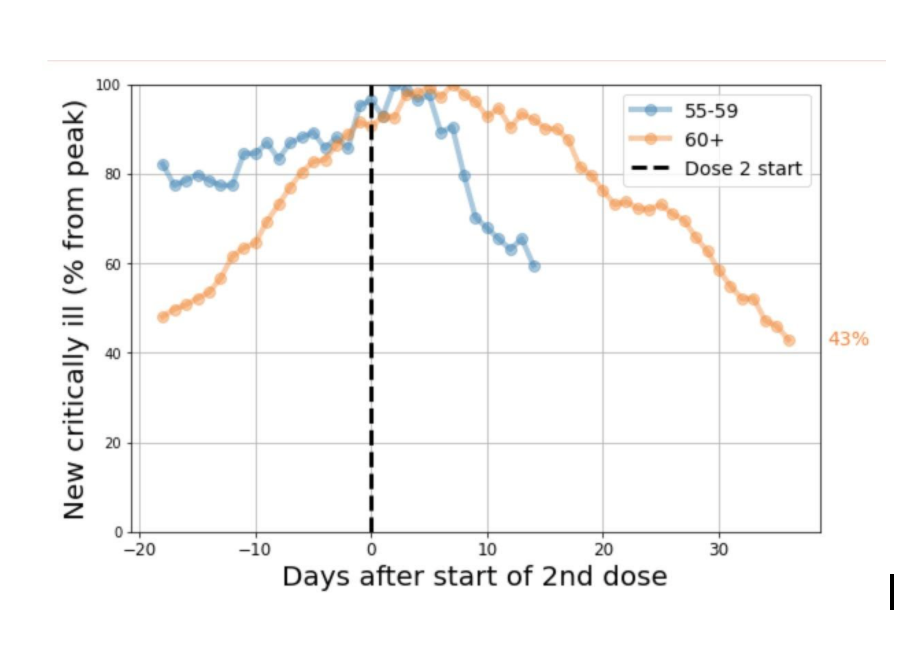

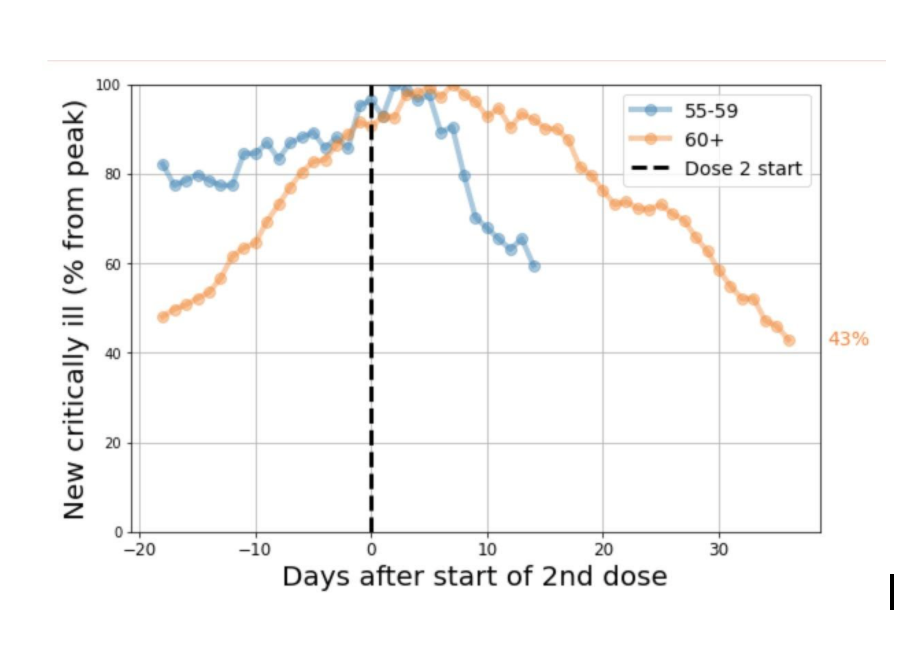

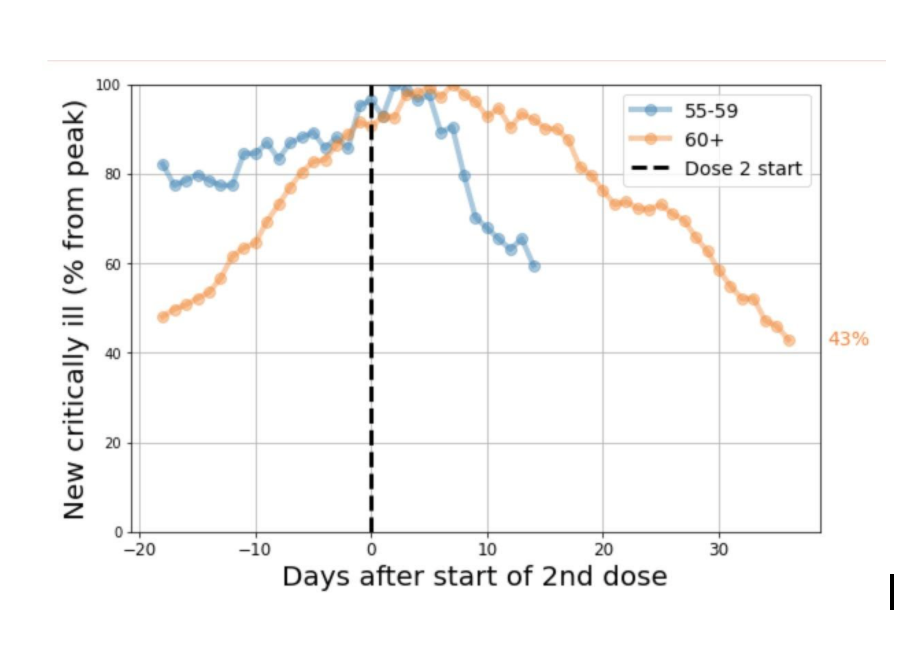

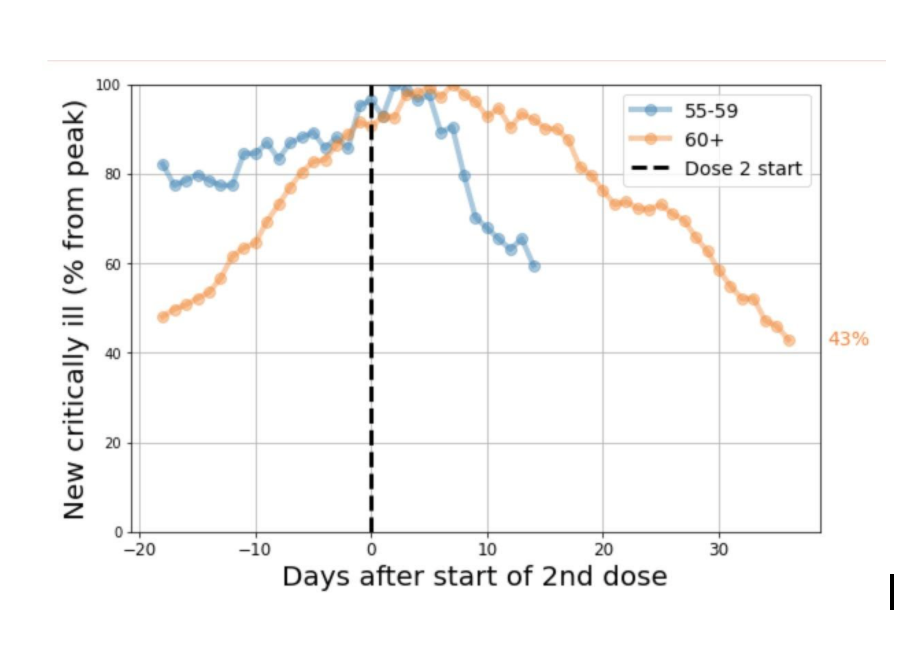

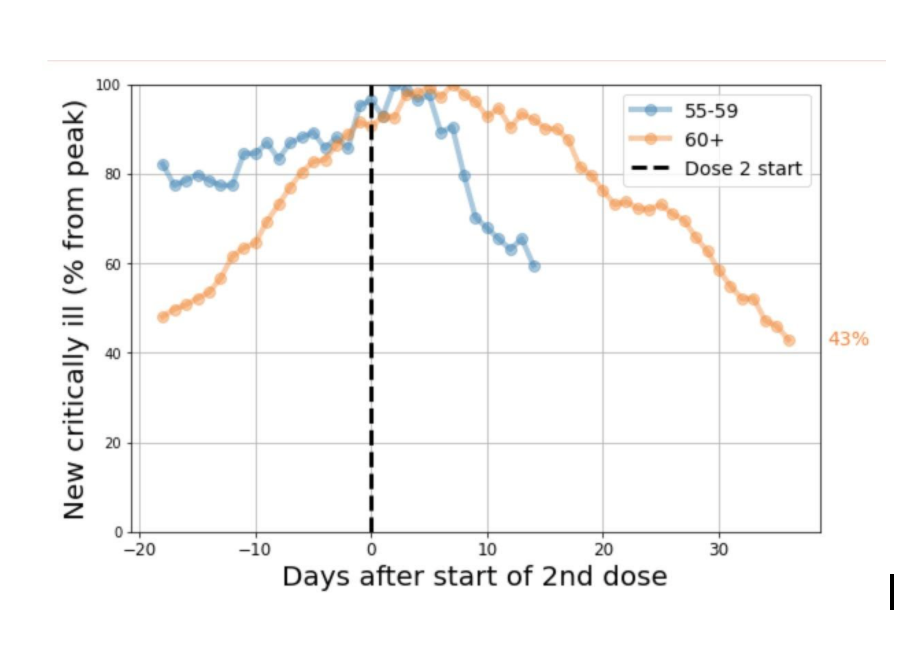

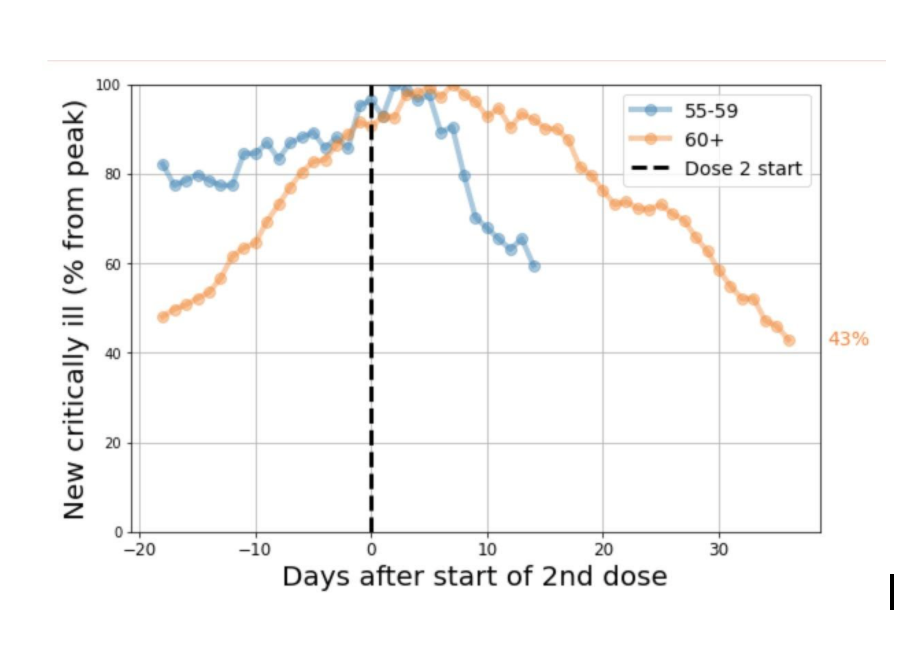

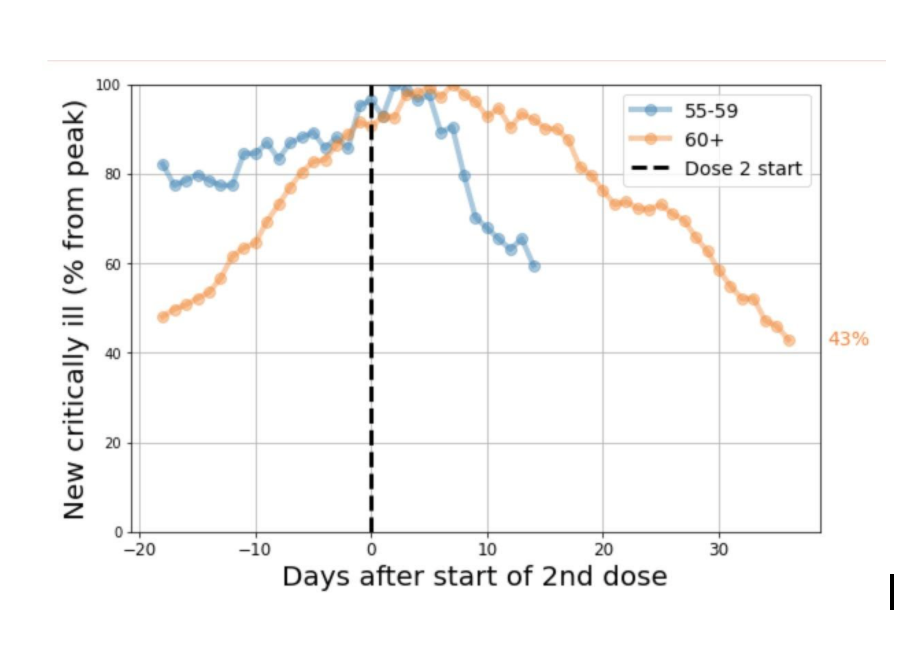

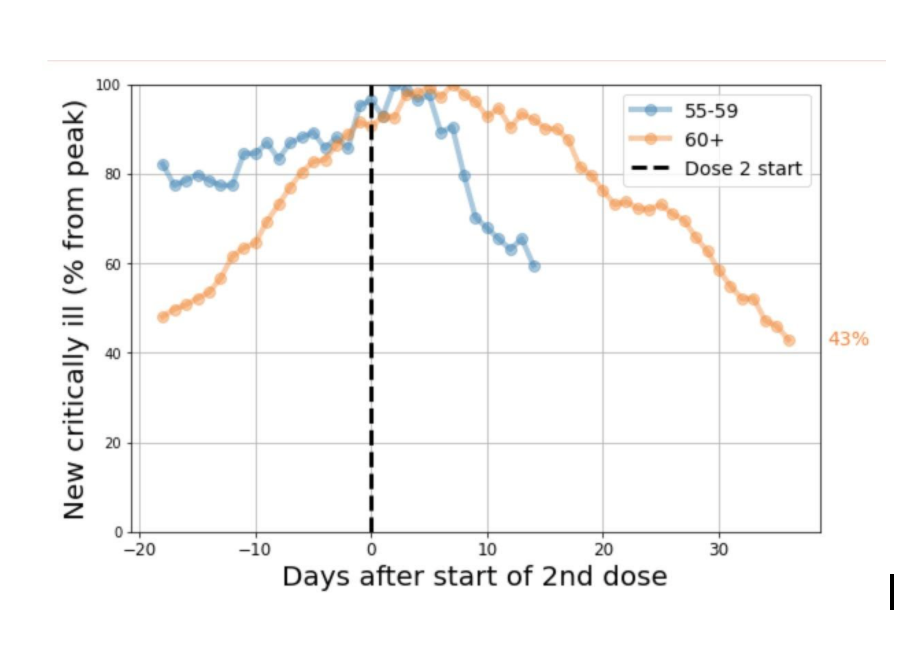

The mRNA (BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna) vaccines and the Oxford/AstraZeneca jab have been in use for almost three months now, and the real-world results are nothing short of miraculous. Israel’s world-beating vaccination drive, for example, has substantially reduced the number of critically ill older patients and infected young people:

Additional data from Israel’s health ministry shows incredible efficacy:

Outside of Israel (which is using only the Pfizer vaccine), other results are trickling in and are similarly positive. For example, the BBC reported on Monday that the U.K.’s vaccination program reduced hospitalizations in Scotland by 85 percent (Pfizer) and 94 percent (AstraZeneca) at only four weeks after the first dose. In particular, Public Health Scotland’s review of 1.14 million vaccinations between December 8 and February 15 found that “there were just over 8,000 people who ended up in hospital, but only 58 were among the vaccinated group after the four-week mark.” In the United States, which is using both mRNA vaccines, there are numerous state-level reports of COVID-19 cases plummeting in long-term care facilities, and nationwide hospitalizations have collapsed (more on that in a sec)—trends that are both due, at least in part, to these amazing vaccines.

There is also increasing evidence that the vaccines are effective at stopping most people from not only getting seriously ill, but also infecting others. As numerous medical experts have noted over the last few months (and as trials have indicated but did not definitively prove), it was always highly likely that the vaccines would greatly reduce virus transmission. However, the mere possibility they might not has been a constant note of caution regarding the vaccines and our broader return to normalcy (e.g., wearing masks, social distancing, and reopening schools or local businesses). Now, we finally have some supporting data from the field, and the results are uniformly great. First, researchers from the Mayo Clinic examined 62,138 individuals in Arizona, Florida, Minnesota, and Wisconsin between December 1 and February 8, and found that “[a]dministration of two COVID-19 vaccine doses [both mRNA types] was 88.7% effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection … with onset at least 36 days after the first dose.” Second, a new study out of Israel found a similar level of efficacy for only the BioNTech/Pfizer shot: a 89.4 percent reduction in transmission (expert review here). Third, a U.K. study of health care workers in England found that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine led to an 86 percent reduction in infection a week after the second dose. The authors’ conclusion: “Our study demonstrates that the BNT162b2 vaccine effectively prevents both symptomatic and asymptomatic infection in working age adults.”

All three studies are preliminary, but they remain a big and wonderful deal, especially since (1) they all say the same basic thing; (2) they basically confirm what medical experts have long suspected (while convincing others to jump on the bandwagon); and (3) even critics note that, while the exact efficacy figures may be off, the overall conclusion (a significant reduction in transmission) is very likely correct. Very exciting stuff.

Even more good news came last week with respect to the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine. First, multiple studies showed that a single dose is highly effective (more than 80 percent) in preventing symptomatic disease a few weeks after it’s administered. Second, following successful internal testing, Pfizer and BioNTech asked U.S. regulators to allow their vaccine to be stored and transported at standard freezing temperatures (-4 F / -20 C) instead of the super cold temps that are currently required. This would greatly expand the number of places in the United States and elsewhere that could store and administer the vaccine, and it comes at the perfect time for the many states that have teamed up with local pharmacies (including Walmart) to ramp up vaccine distribution in the coming weeks.

As George Mason University’s Alex Tabarrok (who’s been a true champ on vaccine issues) adds, the single dose data might unfortunately be wasted on the United States, which appears wedded to the original two-dose approach, but it and the storage development could be a very big deal for developing countries that are just getting started. They also show why we shouldn’t blindly and permanently adhere to the companies’ initial clinical trial data, which were “designed at speed with the sole purpose of getting the vaccines approved” not “to discover the optimal regimen for public health.” We can, and should, keep adapting as the evidence warrants.

Oh but what about those variants?! Again, there’s (mostly) good news and a lot of misguided pessimism (or outright fear mongering). First, both mRNA vaccines and the AstraZeneca vaccine have been shown to be effective against the highly transmissible U.K. variant (B.1.1.7), and its becoming the “dominant strain” in the United States will not necessarily lead to a “fourth wave.” With respect to the other key variant, from South Africa, AstraZeneca struggles to produce sufficient neutralizing antibodies, but Pfizer still works (and Moderna probably does), as does the Johnson & Johnson single-shot vaccine. For people who have had COVID-19, a single shot of the mRNA vaccines also provides protection against the South African variant, which has fizzled out in South Africa and is still pretty limited here.

Variants will remain a cat-and-mouse game between the virus and the vaccines, likely requiring a subsequent booster shot at some point down the road, but (1) declining cases worldwide will decrease the chance for mutation (and thus the number of variants); and (2) the amazing mRNA technology provides a crucial advantage in fighting new variants, in that the vaccines can be rapidly updated (in only 60 days, per Pfizer) and manufactured (in around 110 days, versus “much longer” for traditional vaccines). Even the slow-moving FDA has promised it will fast-track future vaccine booster shots against COVID-19 variants, instead of requiring large clinical trials (wonders never cease). Thus, as the New York Times’ Ross Douthat noted yesterday, the variants will remain a concern for a long while but do not justify a permanent extension of our current bunker mentality.

Of course, all of this good news might be wasted if vaccine supply and distribution lagged. But here again there’s reason for optimism. First, after six weeks of chaos, the United States’ vaccination drive has improved significantly, as many states prioritized speed by, for example, loosening prioritization guidelines, holding mass vaccination events, and expanding the number of distribution sites. As a result, most states have administered 80 percent or more of the doses they’ve received, and the United States has repeatedly exceeded 2 million doses per day—trends that should continue now that the winter storm mayhem is behind us.

Things could certainly improve even more, but today states are mostly using weekly allocations before their next batch arrives. The biggest impediments to the United States’ vaccination efforts thus appear to be the aforementioned public support and supply, which is currently about 10 million to 15 million doses per week. However, anecdotal evidence indicates that vaccines are much more available than they were in January (perhaps due to that frustrating lack of demand in various priority groups), and Bloomberg estimates a major supply surge in the coming weeks:

A review of drugmakers’ public statements and their supply deals suggests that the number of vaccines delivered should rise to almost 20 million a week in March, more than 25 million a week in April and May, and over 30 million a week June. By summer, it would be enough to give 4.5 million shots a day.

Most of this supply (about 500 million of 600 million) will come from the mRNA producers Pfizer and Moderna, and Pfizer subsequently confirmed that it will soon double its vaccine supply to 10 million doses per week. (Moderna just made similar promises.) But Johnson & Johnson will help too, with 20 million doses in March and another 80 million through June, and a final FDA decision on that single-shot vaccine should come in the next few days. Other vaccines, such as AstraZeneca and Novavax, might also get approved this spring. We’ll be swimming in jabs by May.

One can (and should) grumble about various aspects of the U.S. vaccine rollout, but things are definitely looking up. Way up. This of course doesn’t mean that vaccinated people should just throw all caution to the wind—owning a bike helmet doesn’t mean you should cycle I-95—but it’s far past time that we followed Israel’s lead and hopefully portrayed the vaccines as a ticket to normal life.

(Because they are.)

The Virus

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 situation in the United States and elsewhere has improved dramatically since the troubling post-Christmas peak, with cases in many states back to (relatively calm) mid-October levels:

All major indicators of COVID-19 transmission in the United States continue to fall rapidly. Weekly new cases have fallen from 1.7 million at the national peak in early January to fewer than 600,000 this week, and cases have declined in every state. As we’ve seen at many points in the pandemic, case numbers are changing most quickly, with hospitalizations and deaths declining after a delay: cases have been falling sharply for five weeks, hospitalizations for four, and deaths for two. In this week’s numbers from nursing homes and other long-term-care facilities, we are now seeing solid declines in deaths correlated with COVID-19 vaccinations of this most vulnerable population.

As Derek Thompson explains, there are likely four factors driving this rapid and welcome retreat: (1) individual behavior (mobility, masking, etc.); (2) vaccines (see above); (3) seasonality (longer days, warmer weather); and (4) “seroprevalence” (i.e., the number of people who had the virus and now have some level of immunity). Subsequent data show that these trends are continuing, and items 2, 3, and 4 above should only get better in the coming weeks.

These trends have caused some experts to dramatically advance their projections for when a “return to normalcy” might be possible in the United States. Johns Hopkins’ Dr. Marty Makary has probably the boldest prediction, arguing in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last week that “We’ll Have Herd Immunity by April.” His theory, which is plausible but certainly not ironclad, is that the United States has a much higher level of seroprevalence than we think because our weak testing regime has only captured a fraction of all infections. This immunity is driving the aforementioned collapse in COVID-19 cases, he posits, and immunity should only accelerate in the coming weeks as more Americans are vaccinated.

As noted, others challenge Makary’s conclusions, and they are certainly aggressive (and bias-confirming!). That said, even some of Makary’s well-credentialed critics concede that his optimism is generally warranted, and arguably the best COVID-19 forecaster—MIT-trained Youyang Gu, whose website uses artificial intelligence (machine learning algorithms) to predict pandemic timelines—now projects that “[t]he US will be near COVID-19 herd immunity by summer 2021 (Jun-Aug 2021).” He importantly qualifies “herd immunity” not as total eradication of the virus (which we think is where around 80 percent of the population is immune), but as reducing COVID-19 cases, deaths, and hospitalizations in the United States to a level low enough to allow life to “return to normal” here. Regardless of the standard, however, he currently (as of February 21) projects that daily infections will drop to 100,000 in May, 25,000 in June and less than 10,000 by July.

Of course, various obstacles remain and projections change, but there is good reason to think that daily life will be vastly improved—even if not fully “back to normal”—by late spring 2021.

So you may want to start working on your swimsuit body now, just in case.

The Economy

Then there’s the ever-improving economic picture. As noted last week, there are already several signs—wages, jobs, growth, etc.—that the pandemic’s economic damage is today mostly contained (and concentrated), and that the U.S. economy is poised to boom this year if we can control the virus. Since then, there’s been more good news.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDP Now tracker, which incorporates various economic releases in real time, currently projects first quarter GDP growth to hit 9.5 percent, and the bond market is now indicating that the U.S. economy is recovering far more quickly than many experts expected only a few weeks ago. While the GDP Now figure will probably shrink when new data comes in, other forecasts for the first quarter—from Goldman Sachs (6 percent), Morgan Stanley (7.5 percent), and JP Morgan (5 percent)—are also sanguine, and Bank of America has now raised its full-year 2021 GDP projection to a blistering-hot 6.5 percent. JPMorgan further reports that the United States could “out-rebound” China in 2021 and beyond. We can and should debate whether these stimulus-goosed projections are actually good for the U.S. economy in the long run (the stock market is indeed starting to “wobble” a bit), but it’s still quite clear that the nation’s economic despair is in the rearview mirror.

Things are also looking up on the trade front. As I explain in a short paper out today (more on this next week), U.S. manufacturing and those much-maligned global supply chains—even for high-demand medical goods—adapted in the face of generational crisis and ended up performing pretty well overall (though certain problems, such as the global semiconductor shortage, remain). The manufacturing sector is, in fact, almost too red-hot (and would be even hotter if Biden removed Trump’s self-defeating tariffs). The World Trade Organization also reported last week that global trade bounced back in the second half of 2020. Of course, uncertainty—especially in developing countries that are behind the vaccine curve—remains, but this is simply not the panicked global economy of early/mid-2020 anymore.

On the jobs front, Walmart announced substantial pay increases for workers in digital and stocking roles, bringing its average starting pay above $15 an hour and potentially causing other large employers to follow suit: “Whatever the outcome is in Congress, Walmart adds to evidence that wages are moving higher in the private sector. ‘Walmart is an extremely large employer. So if they’re raising wages, that’s going to have a ripple effect up.'” Meanwhile, there’s a “blue collar jobs boom” underway, as national employment and job openings in residential construction, package delivery, and warehousing exceed pre-pandemic levels, while manufacturing jobs numbers are also strong.

Finally, labor markets in midsize cities in the Midwest, such as Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Cincinnati, and Columbus, have fared relatively well during the pandemic (especially when compared with those coastal “superstar megacities” we hear so much about), because they are less reliant on tourism and have diverse economies with both manufacturing and “a larger-than-average concentration of white-collar workers who could shift to remote work.”

The U.S. economy is also showing further signs of adjusting to the pandemic and preparing for life thereafter, continuing trends that we discussed a few months ago. Beyond the aforementioned supply chain adaptation—

-

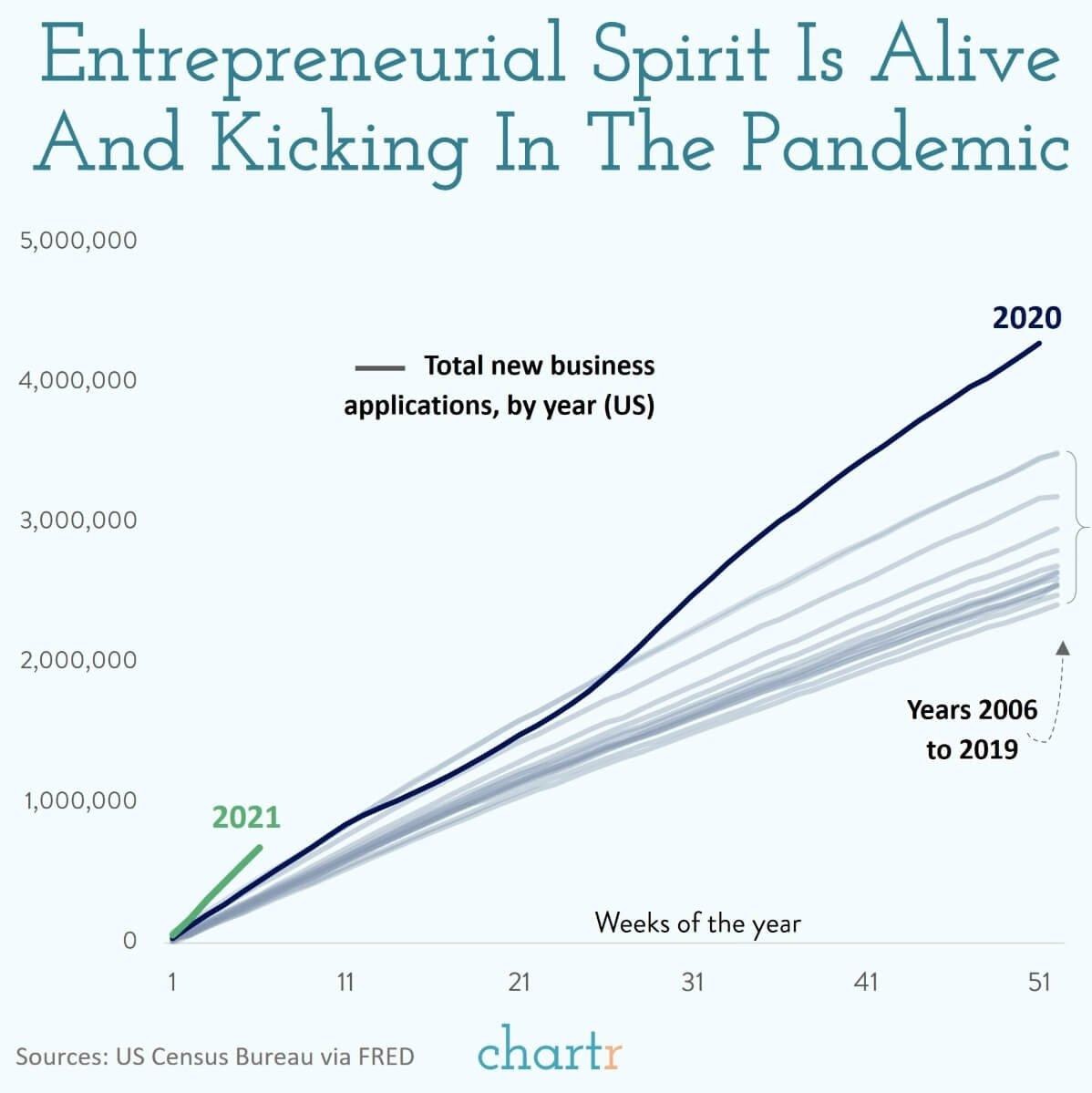

New business applications soared in 2020 and are on a similar (albeit early) pace in 2021:

-

The Wall Street Journal reports that millions of hospitality workers—jobless because of the pandemic and facing an uncertain future—”are trying to launch new careers. Some have transitioned to roles that tap skills honed over years of public-facing work in high-pressure environments. Others have seized the moment to remake themselves for different occupations.” According to the San Francisco Federal Reserve, this type of adjustment could allow the U.S. economy to outperform economies with more rigid labor markets, such as those in Europe, where certain pandemic trends (e.g., increased online shopping or decreased business travel) become the new normal.

In short, we’re not entirely out of the woods and many Americans are definitely still hurting, but the U.S. economy overall is adapting and the future looks pretty bright, as long as we get the virus under control (and don’t shoot ourselves in the foot by enacting “spring 2020” policies in a far different and better U.S. economic environment).

Which Brings Us Back to That Alarmism

And that brings us back to the all-too-common urge among many folks to talk down positive pandemic developments. Some of this—like that local news tweet above—is just “doom porn” and deserves all the derision it gets. But much of it, I think, stems from a sincere desire among cautious U.S. “influencers” to avoid the risk of saying something wrong, encouraging risky public behavior, or appearing glib in the face of real tragedy. But doing so is itself quite risky: Endless pessimism can not only depress the very public actions we need to return to post-pandemic normal—getting vaccinated, looking for a new job, emerging from isolation, etc.—but also undermine public confidence in future official guidance when the increasingly obvious is still-ignored or the always-very-likely becomes the totally ironclad. That risk, unfortunately, is magnified when the cranks and grifters inevitably seize on such messaging as “proof” their crankery/grift was right all along. Indeed, if Dr. Fauci’s 2020 mask debacle has taught us anything, it’s that clever messaging—saying masks don’t work to preserve supply, for example—can backfire badly, and that honesty about the good, the bad, and the unknown, is almost always a better policy than trying to second-guess and manipulate the American public.

And right now, the honest truth is that spring is coming. Pass it on.

Chart of the Week

There’s never been a better time to… rent? (source)

The Links

Me, on steel tariffs, the global semiconductor shortage, and department store jobs

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.